Our recent study investigating non-tolerance to new spectacles1 found that 2.3% of eye examinations resulted in a recheck, similar to the pooled prevalence of older studies of 2.1%.2 With approximately 22.5 million UK yearly eye exams,3 these figures correspond to 0.5 million rechecks conducted in the UK per year.

The actual number of dissatisfied patients is almost certain to be higher, with patients not returning to complain but instead choosing a different optometrist for their next eye examination. Some patients will tell others of their experiences, with 13% of dissatisfied patients telling more than 20 people4 and widespread use of social media suggests this figure may also be much higher. The reputational damage to the individual clinician, practice and profession at large from these numbers of dissatisfied patients is likely to be great. This, together with the financial costs to practices of providing further eye exam appointments at no charge and the costs of remaking spectacles, means the impulse to reduce these as much as possible should be substantial.

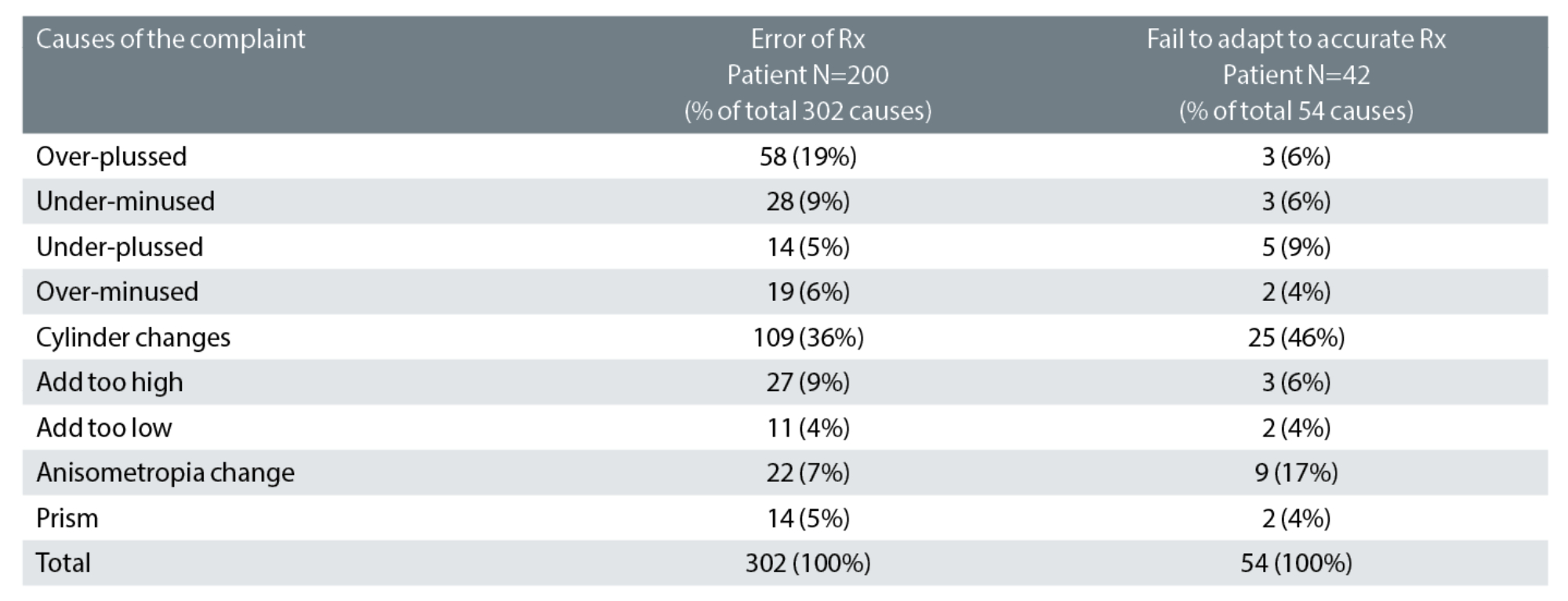

Rechecked patients are often referred to as ‘non-tolerance’ cases, with the implication made that patients could not tolerate (or adapt to) a ‘correct’ prescription and implying that the cause of the problem rests with the patient.5 However, UK optometric practice studies of rechecks reported that only 15% to 17% appear to be due to patient failure to adapt to an accurate prescription.1,5 By far the largest cause of rechecks, at between 72% to 83%, was errors in refractive measurement,1,5 so that the clinician must assume responsibility for the great majority of rechecks.

This should be seen as a positive as it suggests that the great majority of rechecks could be avoided and this article will attempt to describe how this might be achieved.

Figure 1: Listening to reported symptoms and linking these with changes in prescription is essential

What causes rechecks?

Presenting symptoms are not well considered

The over-arching picture of optometric prescribing provided in our recheck study is a huge over-confidence in autorefractor results and a lack of linking prescription changes with presenting symptoms and changes in visual acuity.1 Assuming the clinician believes the patient case history is reliable, this could be as simple as understanding that a patient with no symptoms and reports of good vision at distance and near is likely to have no/minimal change in refractive correction (figure 1). Similarly, a patient who reports good distance vision (DV) but near vision (NV) blur is likely to need no or minimal change in their distance correction and a change in their near correction and vice-versa.

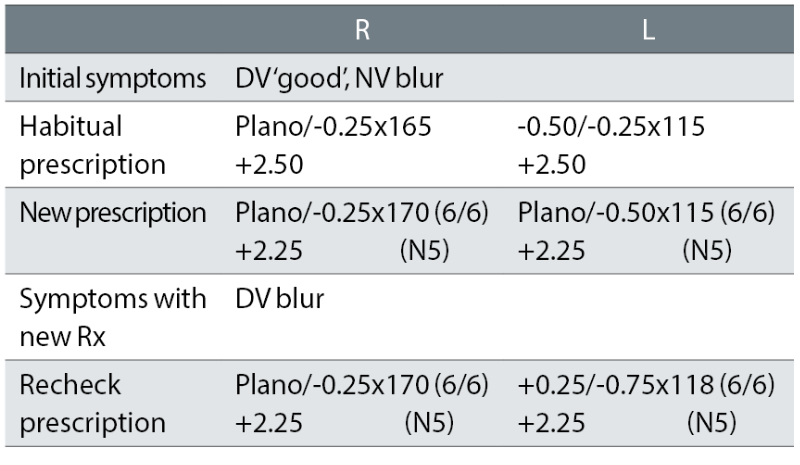

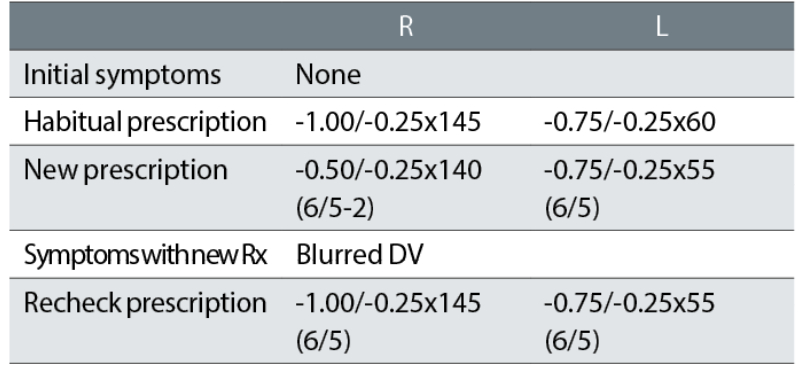

A common example from our recheck study is the following case.

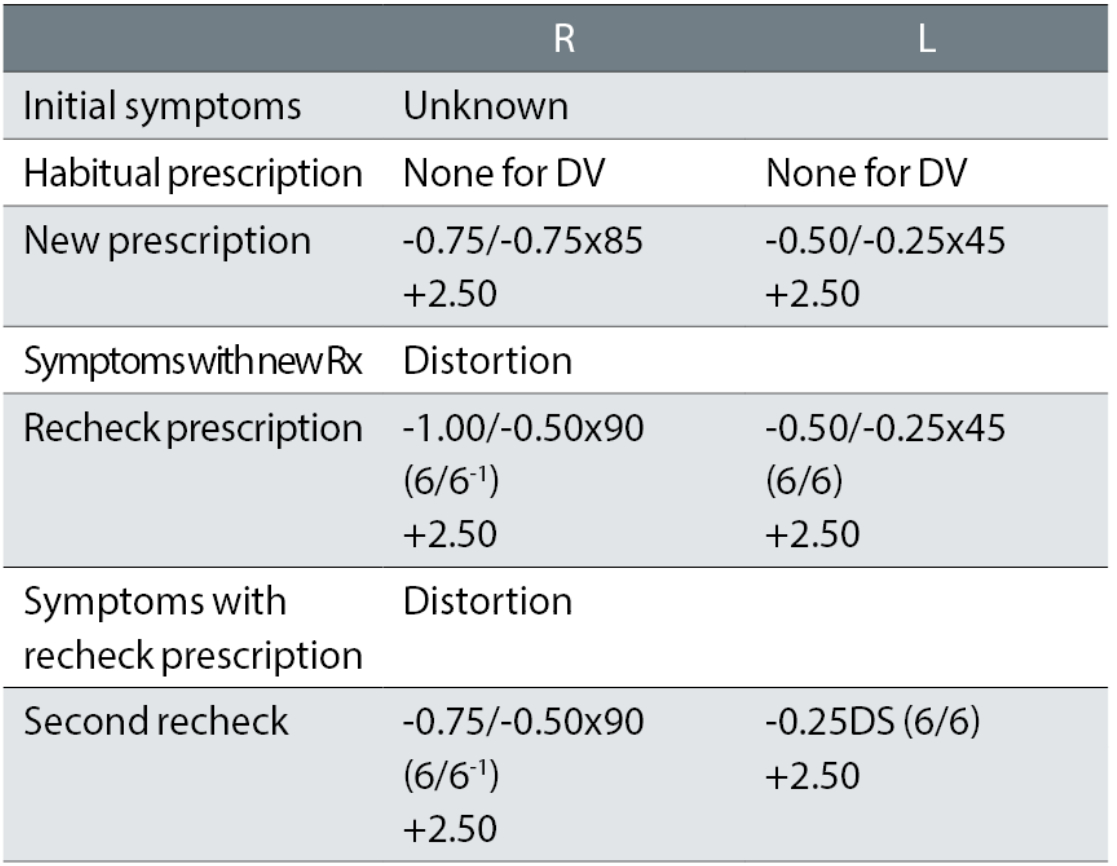

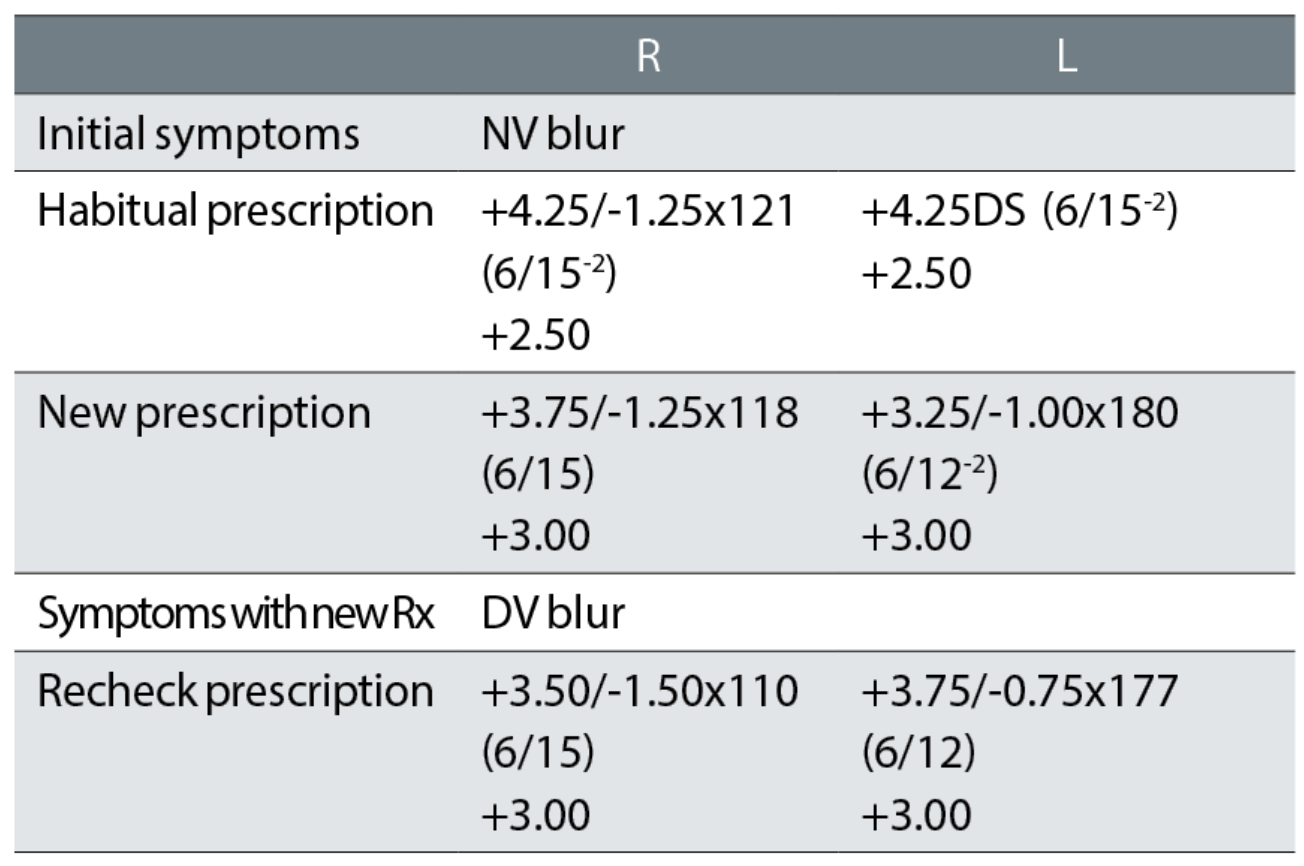

Case example 1: A 63-year-old, wearing DV and NV single vision glasses. Habitual DV and NV visual acuities (VA) were not recorded:

The patient initially reported NV blur and was provided with a R -0.25DS change and a L +0.12DS equivalent sphere change to the near prescription. The DV was reportedly good, yet the change here was larger and in one eye: L +0.37DS.

To attempt to remedy the recheck symptom of DV blur, further plus was added to the left eye and the correction was shifted further away (now +0.50DS) from the presenting habitual correction that gave good DV. Plus, the cylinder was increased by a further -0.25DC and shifted 3°. Both corrections show no link with symptoms and no change in visual acuity (VA), with minor swings in cylinder evident and possibly indicative of a reliance on autorefractor measurements.

This lack of a logical change in correction at the recheck examination was a common finding. In half of the rechecks of originally asymptomatic patients, more than half the difference between the presenting habitual correction and initial prescriptions was maintained, despite the patient having no reported symptoms with their habitual prescription. The recheck correction was thus closer to the initial correction (that produced symptoms and was the cause of the recheck) than the habitual correction that caused no symptoms. This suggests that the optometrists were not thinking about the link between symptoms and prescription changes when prescribing. The clinicians appeared to just prescribe the subjective refraction result, with some cylinder values seemingly dependent on autorefractor results.

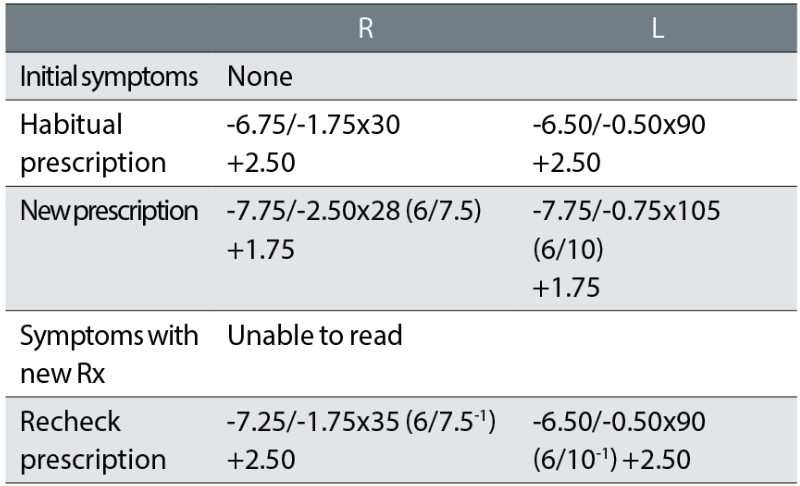

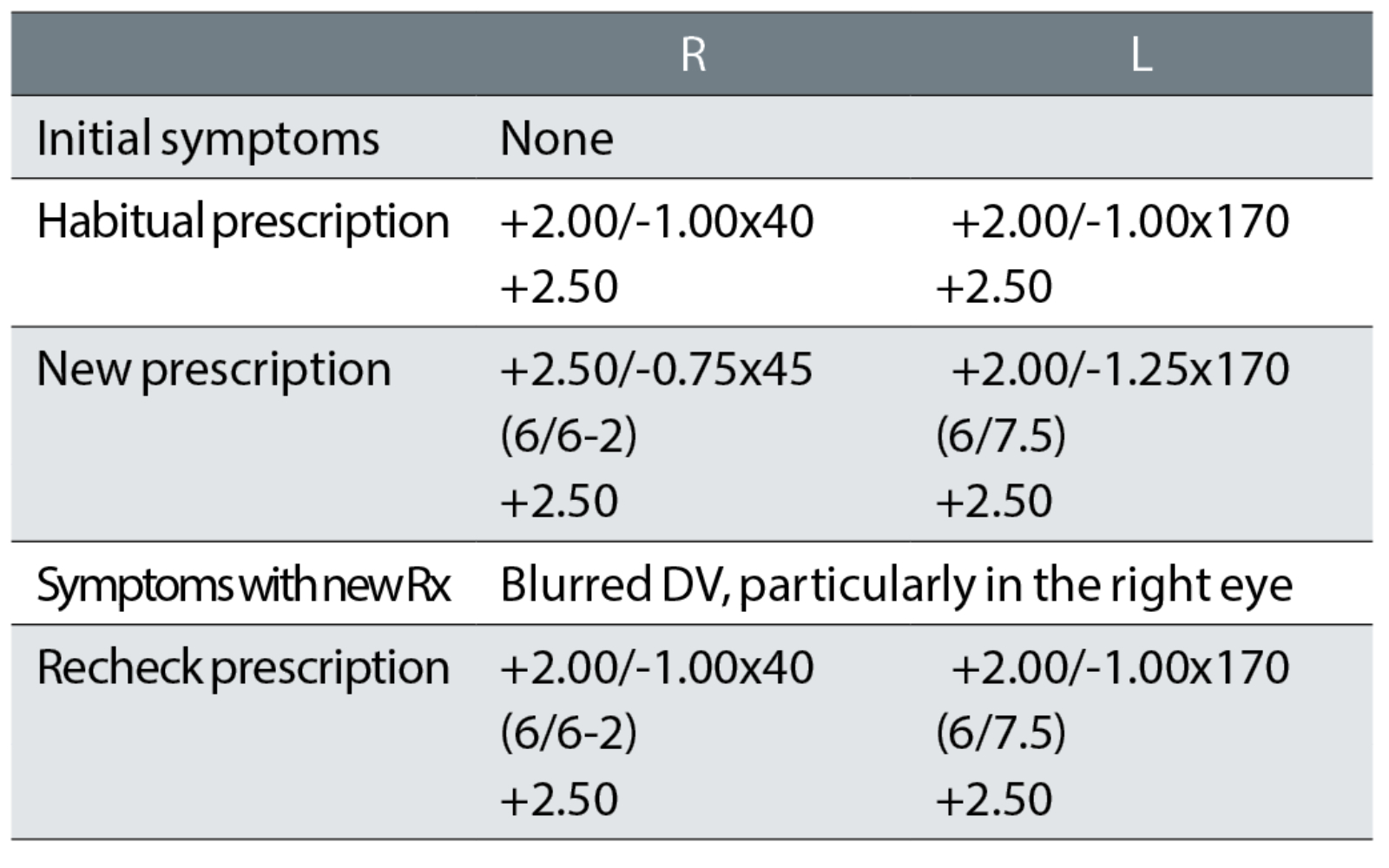

More extreme cases were not uncommon in the initial corrections and some of these were corrected at the recheck, such as the following:

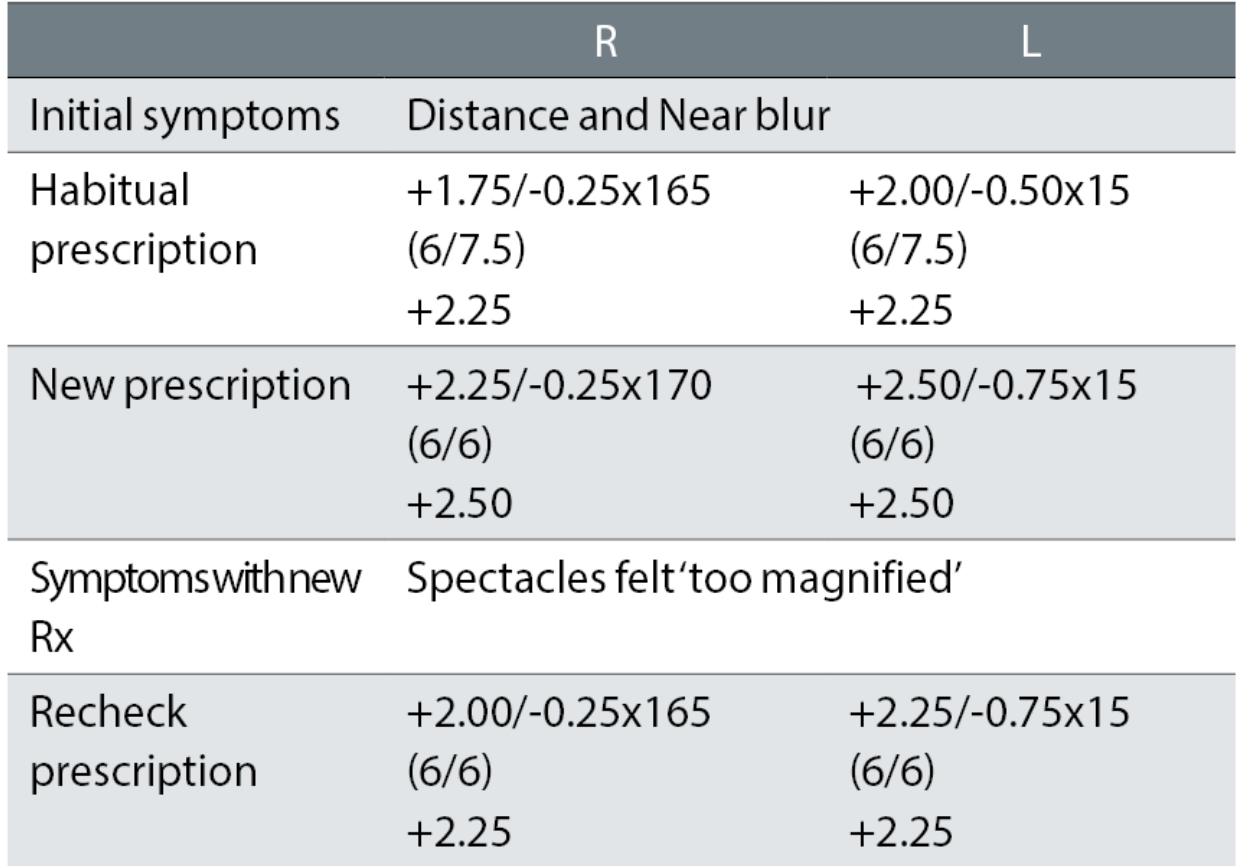

Case example 2: A 65-year-old varifocal wearer, with mild nuclear sclerotic cataract, reporting no problems with their current varifocals. No vertex distances were recorded:

Considering the patient reported no problems with their current spectacles, the initial exam made some surprising changes to the prescription, with -1.37DS added in both eyes. This is a huge change in correction in a 65-year-old varifocal wearer given that refractive changes of greater than ±0.75DS have been shown to increase fall rates in older patients by approximately 50%.6 We assume that this correction was based on an autorefractor result. Surprisingly, the reading addition was also dropped, so that the NV correction was changed by -2.12DS. Both cylinders were changed, with a -0.75DC increase in the right eye and a 15° axis change in the left.

On collection of the new varifocals, the patient not surprisingly reported being unable to read and they refused to take the glasses. The recheck clinician reinstated the prescription in the left eye and retained a small increase in minus in the right, and the -1.75DC cylinder axis was changed by 5° towards the oblique from the habitual. The patient reported being happy with the remade spectacles. This tendency for the recheck clinician to include a few minor tweaks (particularly in cylinder axis) when returning a correction to the original habitual one that a patient was happy with, is common. This is a risky strategy, given that oblique cylinder changes such as in this case are a common cause of problems (see later).

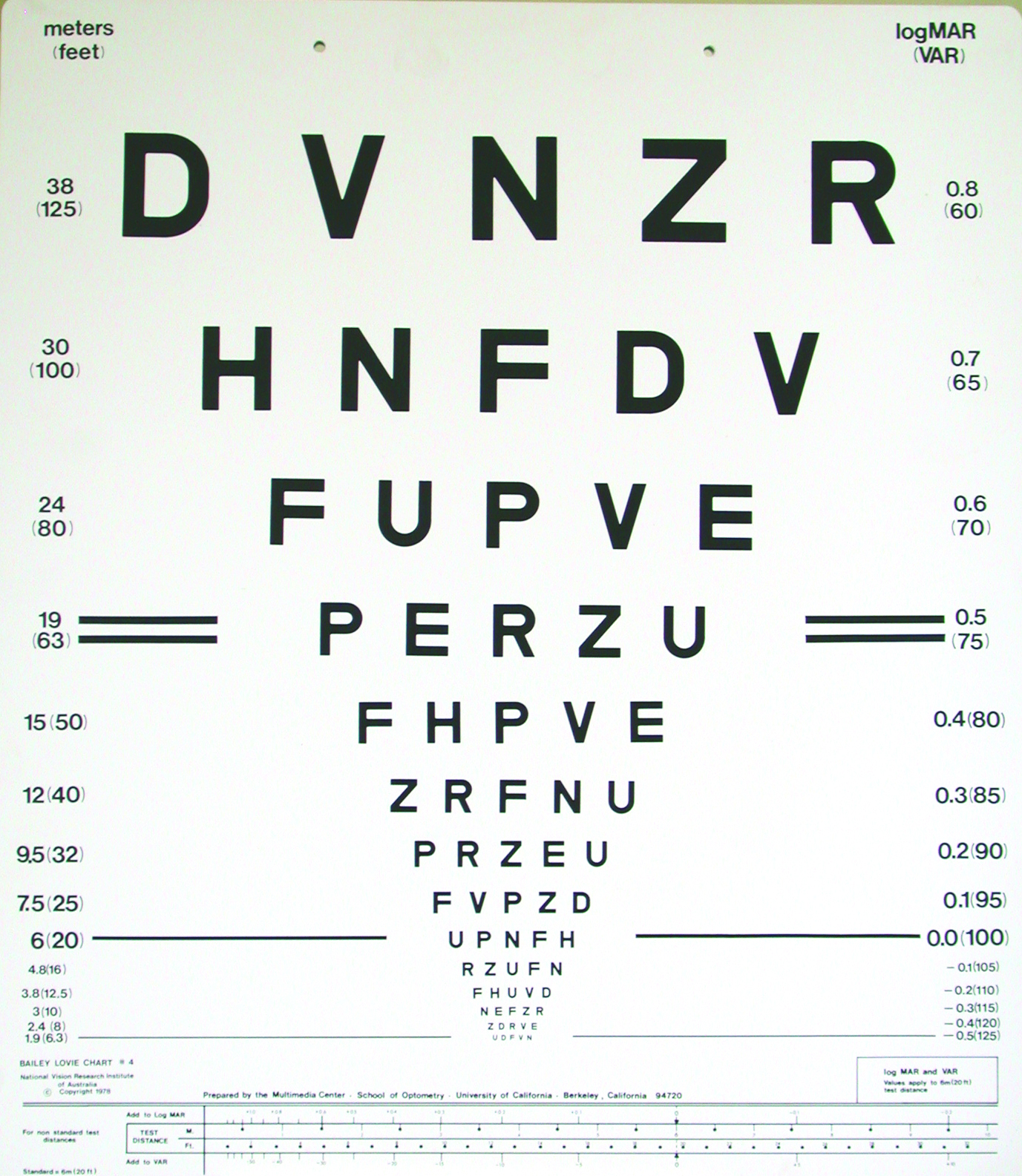

Habitual visual acuity is often not considered

A very important part of determining whether a new refractive correction is appropriate is, firstly, determining whether it improves distance VA beyond that provided by the habitual correction and, secondly, determining whether the improvement in VA matches the change in correction. The latter is typically assessed by using a rule that equates -0.25DS with one line of a logMAR VA chart (figure 2). As the great majority of rechecks involve older patients,5,7,8 this can be expanded to ±0.25DS being equivalent to approximately one line of logMAR VA.

Figure 2: By rule-of-thumb, -0.25DS equates to one line of a logMAR acuity chart

Case example 2 is indicative of the problem in that -1.37DS was added to a DV correction, and yet VA was not measured in the presenting habitual glasses. So, it was impossible to determine whether this very large change in correction actually improved VA beyond that with the current glasses. For some reason, visions (unaided VAs) were recorded in this exam as ‘hand movements’ in both eyes. Why this measurement was taken and not habitual VAs is unclear and, unfortunately, this was not an uncommon finding in our study. Of the records checked, only 11% had recorded monocular habitual VAs at the original exam, some had visions or habitual VAs only taken at the recheck examination (11%), some measured only binocular habitual VA (20%), many measured visions (unaided VAs) but not habitual VAs (38%), and the remainder had no visions or habitual VAs taken at initial test or recheck.

Case example 1 illustrates the need to measure VA accurately. With no DV symptoms, the distance prescription was changed at the test and changed further at the recheck, but with 6/6 recorded as best VA for each eye for both the first exam and recheck. It seems likely that 6/6 was the smallest line used and the clinicians readily accepted the initial point when a patient stated that they could not see any more. Other clinicians, however, take unhurried measurements, giving patients encouragement and pushing them to guess and gain better VAs as a result.9

Poor prescribing with asymptomatic patients

The ‘happy myope’

Slightly more than one third of our rechecks (N=96) involved patients who reported no visual problems with their current spectacles (or unaided vision) at their original eye exam and a further 17 patients who reported no problems with their distance vision but, following a change in prescription, reported distance problems at the recheck (as with case example 1).

The changes are typically small and may be deemed negligible, but they are not. Considering all 242 prescription-related cases in our recheck study, 86% had a recheck prescription differing from the non-tolerated prescription by ±0.50D or less. Some of these included younger patients and, most typically, myopes who were happy with their current glasses but were provided with a weaker minus correction.

Table 1: Categorisation of the likely causes of the 242 prescription-related cases. 54% had one likely cause, 41% had two and 5% had three or more causes. Key: Rx: spectacle prescription

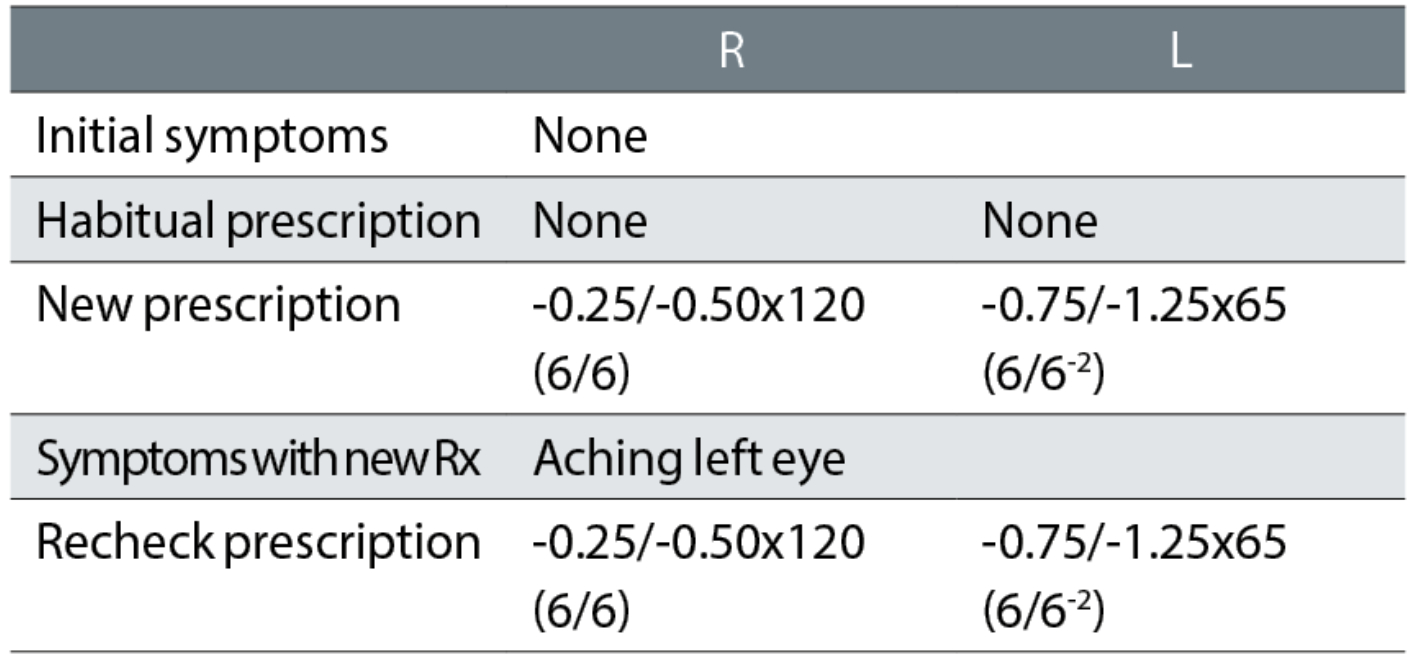

Case example 3: An 18-year-old patient, reported no symptoms with their current spectacles and simply wanted a new pair:

The correction of this ‘happy myope’ was reduced in the right eye, with resulting DV blur symptoms. The recheck reinstated the minus of the habitual spectacles and the patient was happy with the remade spectacles. The change in correction was essentially a -0.50DS reduction in the right eye and might seem minimal. However, it must be noted that a refraction is not typically performed in the far distance but at 6m, which is equivalent to +0.17DS. When refractions are performed at 4m, it is standard to add -0.25DS to the distance correction to compensate, but because we currently provide corrections in 0.25DS steps, a -0.17DS correction is not made for 6m. This is despite +0.17DS being much closer to a +0.25DS overplus than zero. Adding -0.25DS routinely to the subjective refraction performed at 6m may not be appropriate, but the +0.17DS overplus should be considered when changing a prescription, particularly with a happy myope.

Also note that an 18-year-old will have approximately 12 DS of accommodation and accommodating in the distance by just 0.25DS is not a problem. Although refraction techniques may support ‘pushing the plus’ or ‘maximum plus for maximum VA’,10-13 this does not mean that prescribing lowered myopic corrections for happy myopes should be similarly supported. They are often rechecks waiting to happen. The mantra in subjective refraction of ‘maximum plus for maximum VA’ needs to be balanced with greater knowledge and understanding of prescribing maxims such as ‘don’t reduce a happy myope’.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

Many recheck patients attended their original examination without symptoms and were happy with their DV and NV.

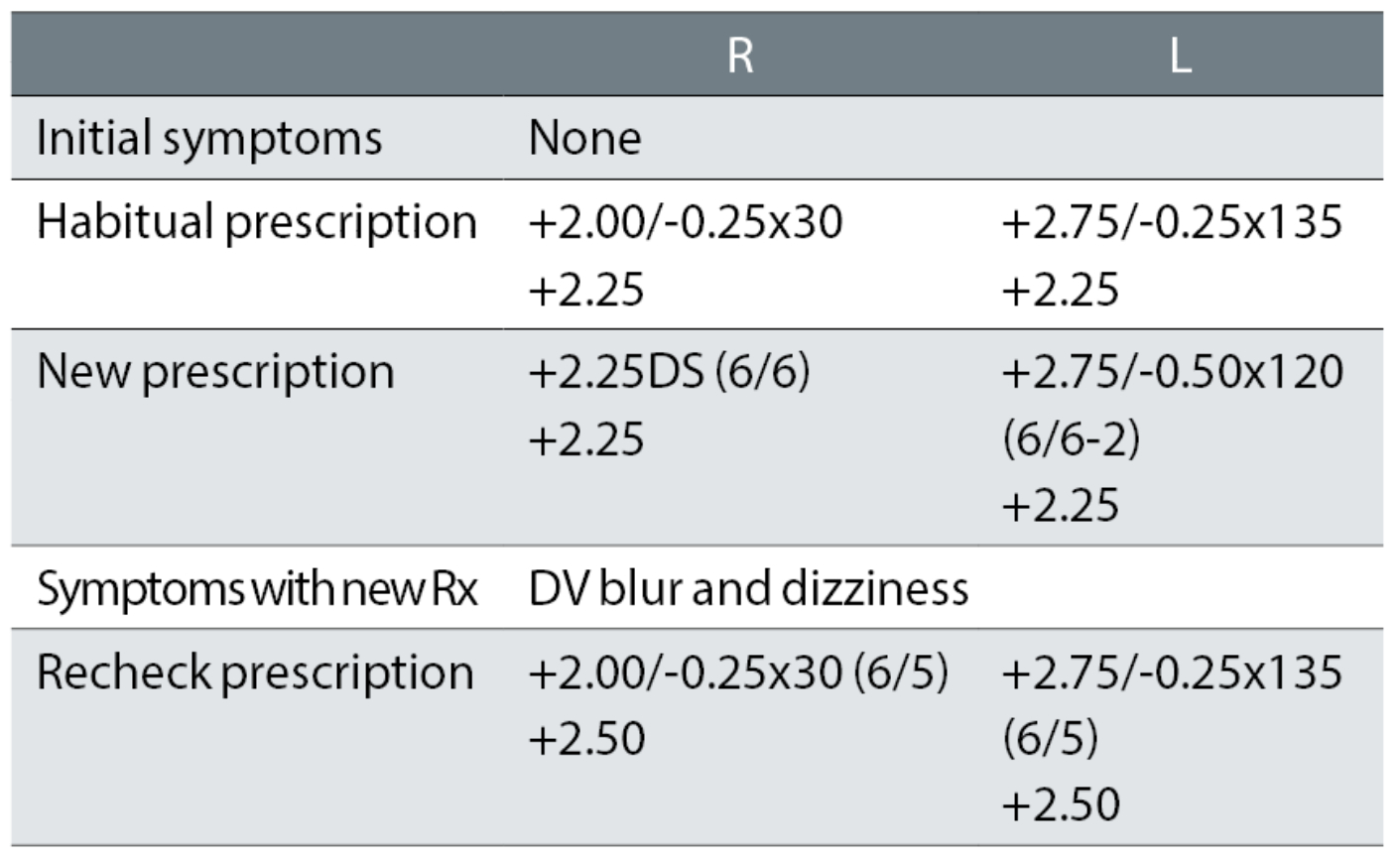

Case example 4: A 74-year-old patient, who reported no symptoms with their bifocals and just wanted another pair of glasses:

Despite no symptoms and the sole habitual VA measurement at the test of 6/7.5 -1 binocularly, the distance correction was increased by R +0.62DS and decreased by L -0.12DS, together with a change of the right cylinder of 5° towards the oblique. At the recheck examination, the correction was returned exactly to the original correction that the patient was happy with.

This recheck could have been avoided by using the most commonly promoted prescribing rule: ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’.7, 14-18 This is the optometric equivalent of the medical maxim ‘above all, do no harm’. In other words, if the patient reports no symptoms with a pair of glasses and is happy with the DV and NV and the monocular habitual VAs are at age-normal levels, then do not change the correction. All you can do by changing the correction of this happy patient is to make them unhappy. This is the most common cause of rechecks in all published studies, at about 33%.1,5

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it much

Some patients may report no problems with their current spectacles but may still benefit from a small change. Take, for example, a patient with +1.00DS R and L and +2.00DS Add who reports strain while reading but no distance vision problems with their varifocals. A subjective result of +1.50DS R and L and +2.00DS Add might satisfy their reading problems. However, a better, modified prescription might be +1.25DS R and L and +2.25D Add, thus solving the reading problem, not over-correcting the distance and not giving too large an increase in the distance-to-near gradient in the varifocals, thus easing adaptation. They would also still benefit from slightly easier middle-distance vision, without the backwards head tilt patients often use with varifocals to compensate for a hyperopic change.

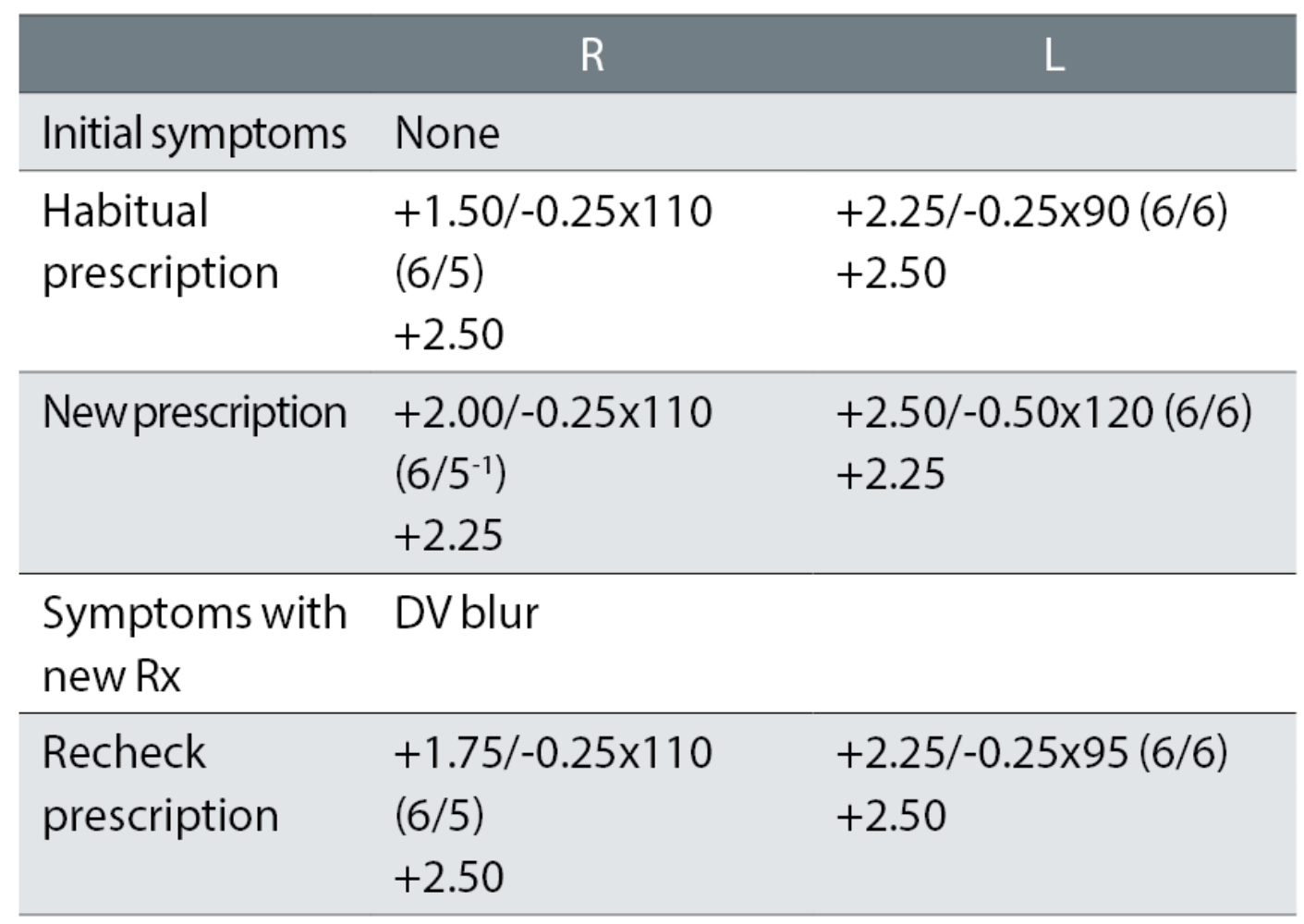

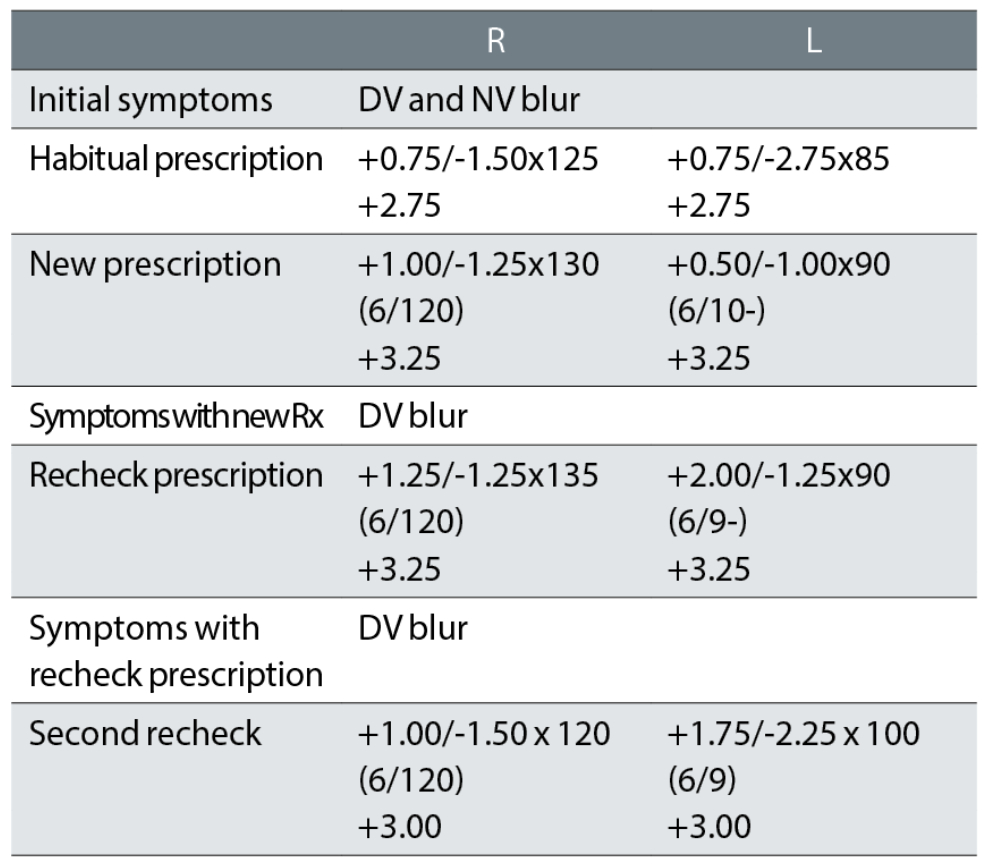

Case example 5: A 66-year-old, reporting no problems with their current varifocals:

At the first exam, the plus was increased (R +0.50DS and L +0.12DS), possibly causing the need for a reduced addition. The left cylinder was increased and changed by 30° towards the oblique, for no apparent improvement in VA. The recheck retained +0.25DS in the right eye and changed the left cylinder (almost) back to the habitual. The patient was happy with the remade spectacles. An initial change of +0.25DS to the right eye (remembering, ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it much’) with no change in cylinder axis in the left eye would have avoided the recheck. This is further discussed in the next section.

Cylinder changes are a common cause of rechecks

Table 1 indicates the likely causes of 242 prescription-error related cases of rechecks.1

Of the 302 causes of prescription-related errors, the greatest proportion were cylinder power and/or axis errors, at 36%. Approximately 20% of astigmatism is oblique19 and, consequently, it might be expected that just 20% of astigmatism-related errors would be attributable to oblique cylinder changes. In our study, we found more than double this proportion (42%) had oblique cylinder changes. Additionally, 43% (13 out of 30) of patients who reported symptoms of dizziness had oblique cylinder changes and, of 66 patients who reported a problem within two days of collection of new spectacles, 46 (70%) had cylinder changes of which 23 (35%) were oblique.

The proportion of the ‘failure to adapt to an accurate prescription’, attributed to cylinders was even greater, at 46%. This underlines the care which needs to be taken with cylinder changes, especially when oblique and even when small.

Case example 6: A happy 63-year-old varifocal wearer with no symptoms:

The only changes at the initial exam were a removal of a -0.25DC oblique cylinder in the right eye and a -0.25DC change to the oblique cylinder power and 15° axis change in the left. At the recheck, the correction was returned to the original DV correction, with +0.25DS added to the addition, with which the patient reported being happy. This illustrates how apparently small prescription changes can cause big problems, particularly with oblique cylinders.

Case example 7: A 71-year-old, with no previous distance correction. The original eye exam was performed at another practice, with initial symptoms unknown:

The patient reported being happy with the spectacles remade to the second recheck prescription. It is likely the distortion in the first spectacles was caused by the first cylinder corrections of -0.75DC in the right eye and an oblique -0.25DC in the left. While the first recheck reduced the right cylinder, the left was retained with the same symptoms of distortion reported with that correction. The second recheck kept the minus to a minimum, considering this was a first distance correction and, more importantly, removed the left oblique cylinder while keeping the reduced cylinder in the right eye.

Over-plussing is much more of a recheck problem than under-plussing

The second most common cause of rechecks, causing 28% of cases, was over-plussing or under-minusing. In contrast, just 11% were under-plussed or over-minused and these figures are similar to previous recheck studies.5, 20 Some of these are due to reducing minus corrections in young, happy myopes as considered earlier. However, as could be expected, over-plussing was particularly prevalent in patients over the age of 60 years who have little or no accommodation: more than 10 times as many were over-plussed/under-minused as under-plussed/over-minused.

Case example 8: A 68-year-old, varifocal wearer:

A change in correction was needed given the symptoms of DV and NV blur. The changes of R +0.50DS and L +0.37DS and -0.25DC for the distance correction and R +0.75DS and L +0.62DS for the NV correction were too much. The recheck correction reduced the changes to R +0.25DS and L +0.12 in both the DV and NV corrections, retaining the -0.25DC change in the L. These were small changes, in both the degree of change which caused the problem and which subsequently fixed the problem, resulting in a happy patient. The recorded VAs, with no +/- letters suggesting threshold acuities slightly better or worse than the 6/6 line (or 6/7.5 line for the habitual), makes reconciling prescription change with improvements in acuity difficult.

Near working distance issues

The increase in reading adds with age is bilinear, with a steep increase up to the age of 55 years as amplitude of accommodation decreases, followed by a much slower increase that is reflective of decreased working distance in some patients. In patients over 60 years, the reading add is determined by the patient’s working distance. Working distances were rarely recorded in our recheck study (figure 3).

Figure 3: Working distances are rarely recorded

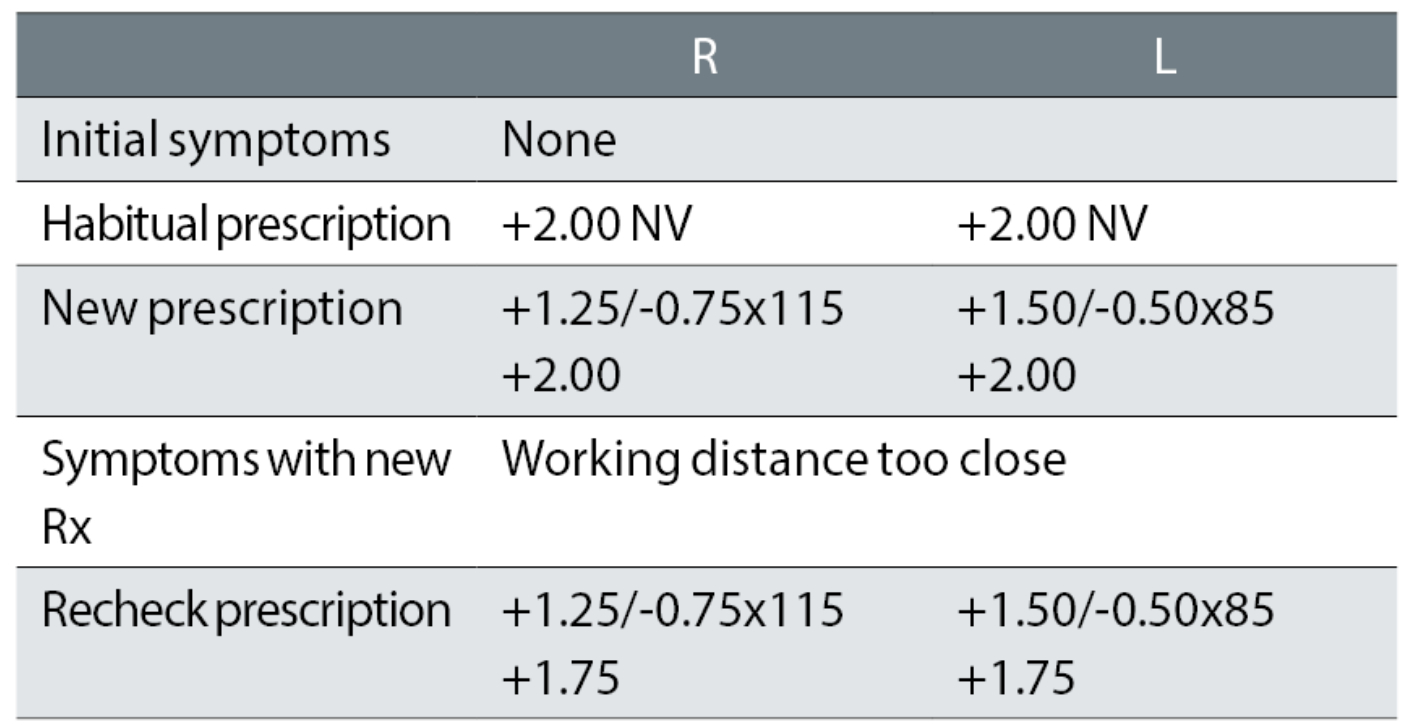

Case example 9: A 67-year-old asymptomatic patient wearing NV single vision glasses only. VAs were not available, but may have been measured:

The patient’s reading glasses were increased from +2.00DS R & L to an equivalent sphere of approximately +3.25DS, despite no symptoms or reports of poor NV. Not surprisingly, the patient reported too close a working distance with the new glasses. It seems highly unlikely that the recheck correction, that reduced the add by just -0.25DS and thus altered the change from the habitual readers to +1.00DS, would have fixed the problem.

Notably with this case, the reported problem was treated purely as a working distance issue, with no apparent consideration of the degree of change from the habitual spectacles, by way of both an increase in plus power and a first cylinder of -0.75DC. The case also illustrates the cause of many rechecks in our study, in that the near prescription was too strong resulting in too close a working distance for the patient. More than twice the number of problems were caused by too high an addition than too low (9% versus 4%).

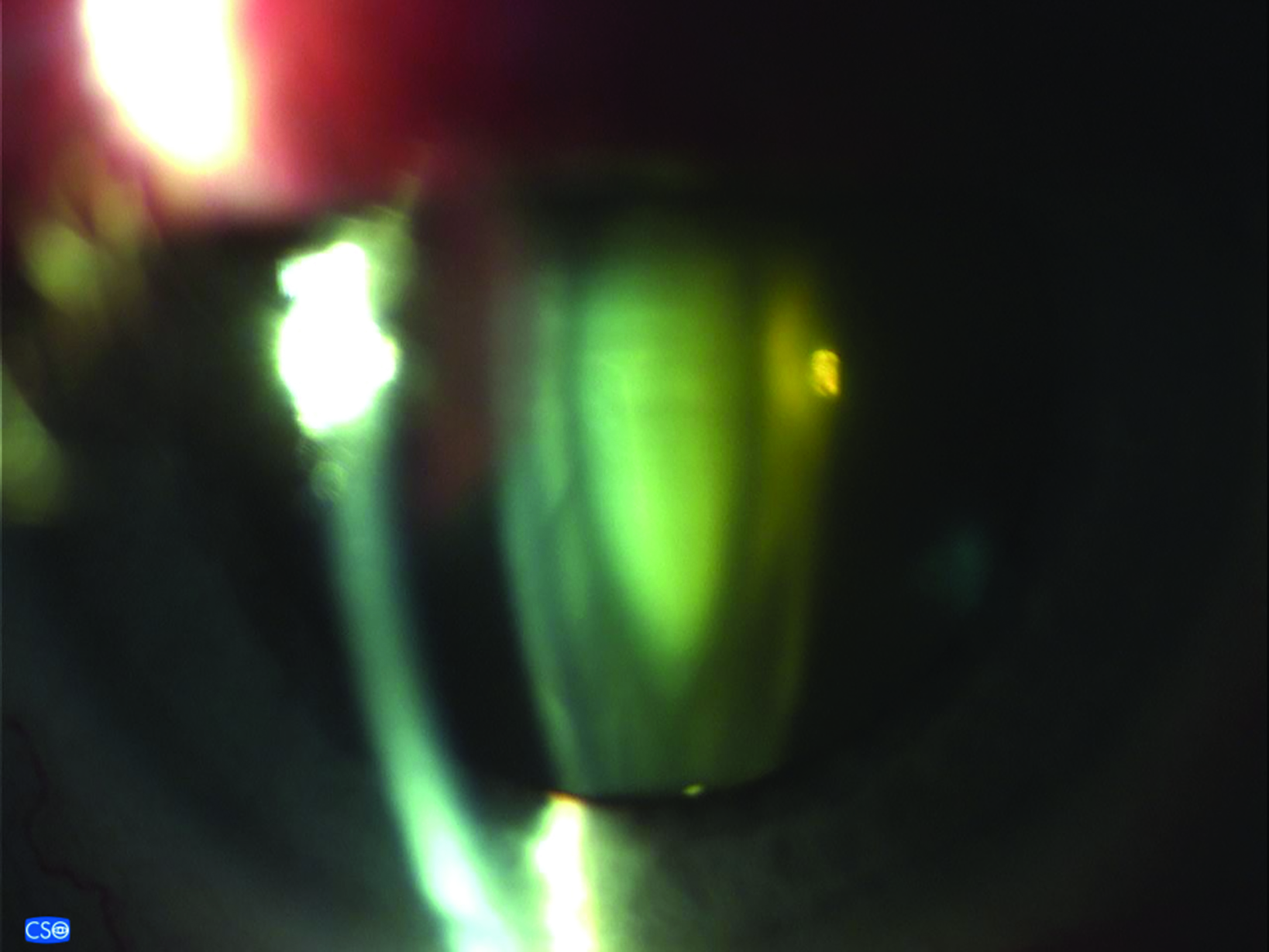

Large changes in correction are often a problem in older patients

Particular care needs to be taken with larger prescription changes in older patients. These might result from cataract, for example large myopic changes from nuclear sclerosis or cylinder changes from cortical cataract. While a -0.25DS change in prescription is equivalent to approximately one line of logMAR acuity,18 the presence of pathology, such as cataract, might reduce the magnitude of improvements in VA per unit of prescription change (figure 4).18 For such patients, issuing a full prescription change might not be appreciated visually by the patient, but would increase the likelihood of a non-tolerance.

Figure 4: Larger changes in prescription in older patients may result from cataract and need to be treated with care

Therefore, where large changes of prescription are determined subjectively, only part of such changes should perhaps be prescribed, particularly for the elderly.18

Case example 10: A 86-year-old patient, wearing bifocals, with cataract for which they did not want to be referred:

A -0.50DS change in the right eye for a negligible two letter VA improvement and a -1.50DS equivalent sphere change in the left eye for a one-line VA improvement does not make sense, even in a patient with nuclear cataract. Compounding this patient’s problems was an anisometropic change of 1.00DS and the introduction of a -1.00DC cylinder to the left eye, which is also a large change for an 86-year-old patient. The recheck prescription removed the anisometropic change by reducing the change from the left eye to -0.87DS and the cylinder to -0.75DC, but strangely decreased the right eye correction by a further -0.37DS with an 8° further change in cylinder axis for no improvement in VA.

Poor quality rechecks

The standard process in the practices where our recheck data were collected was for rechecks to be randomly assigned to clinicians in the same way that all other appointments are assigned. In our study, 96 (40%) of rechecks were deemed unsatisfactory by two experienced clinicians. The reasons for this categorisation included the following:

- Issuing a prescription that failed to address the symptoms at either test or recheck (N=47)

- One problem was fixed, but another was likely caused (N=26), for example, correcting an under-minusing problem but also prescribing vertical prism when no binocular vision problem was reported

- No change in prescription was found but a change appeared to be required from the symptoms (N=11)

- There was a need for a second recheck (N=8)

- A refund was required (N=4).

Case example 11: A 27-year-old asymptomatic patient, with no current spectacles and who reported no DV problems:

The unaided visions were not recorded at the initial exam or recheck, making it impossible to reconcile changes in prescription with improvements in acuity. Using the rule of one line of logMAR VA per -0.25DS of equivalent sphere, the habitual VAs should have been approximately R 6/9 and L 6/24. A first cylinder of -1.25DC with an axis approaching the oblique was likely responsible for the symptoms with the new spectacles. Despite the reported symptoms, the practitioner undertaking the recheck made no attempt to resolve the issues and, instead, informed the patient that the prescription was correct and that adaptation would be required. The patient was not subsequently followed up, so their adaptation, or perhaps lack of it, remain unknown.

This is a classic example of an apparent failure to reconcile symptoms with any prescription change and, even if this was an accurate full subjective prescription (and not simply the autorefractor result), some modification of the prescription was clearly required.

Case example 12: A 71-year-old, wearing DV and NV single vision spectacles, with macular degeneration in the right eye:

At the initial exam, no VAs were recorded with the habitual spectacles, just unaided visions of 6/120 R and 6/18 L, making it impossible to reconcile changes in prescription with changes in VA. Changes were minor in the right eye and that eye had a very poor VA of 6/120, so that the patient was relying on the left eye with VAs around 6/9 to 6/10. The subsequent minor tweaks to the right correction seem irrelevant, presumably based on autorefractor results, and are ignored.

The initial correction reduced the left cylinder power by a huge -1.75DC and the patient returned complaining of poor DV. The first recheck left the cylinder very similar to the new correction but increased the sphere by +1.50DS. This changed the equivalent sphere and cylinder from the habitual glasses by +2.00DS and +1.50DC in a 71-year-old with one functioning eye. The second recheck reinstated much of the cylinder in the left eye although changed the axis to 100° from 85° and 90° previously, with a change in equivalent sphere from the habitual correction of +1.25DS. The patient did not return to the practice again and reported being happy with this correction when telephoned.

How to avoid rechecks?

First, remember there are about half a million rechecks a year in UK optometry practice and about 75% of rechecks are due to clinician error at the initial refraction. This needs to be accepted: in most cases they are not ‘non-tolerances’ and it is not the patient’s ‘fault’. On the plus side, this means that, with a little care, most rechecks can be avoided. Including recheck numbers as a key performance indicator and providing clinicians with feedback regarding how each recheck could have been avoided seems an eminently sensible practice.

Consider the presenting symptoms

This could be as simple as understanding that a patient with no symptoms and reports of good vision at distance and near is likely to have no or minimal change in refractive correction, particularly if habitual VAs are at previous levels or age-normal levels.

If it ain’t broke, either don’t fix it or don’t fix it much

Similarly, if a patient reports DV blur, the DV correction likely needs changing and, if the patient reports NV blur, the near correction (which is the DV correction plus the Addition) needs changing appropriately. Thus, a patient who reports good DV but NV blur is likely to need no or minimal change in their distance correction and a change in their near correction. In other words, the Addition change should be greater than any DV correction change.

Measure habitual VA (or visions in patients without glasses) and reconcile changes in prescription with improvements in VA

First, habitual VAs must be measured. Otherwise, it is impossible to determine whether the latest subjective refraction is any better than the current glasses. That must be the first check of a subjective refraction: is the VA of each eye any better than the corresponding monocular habitual VA?

Subsequently, a check on whether a change in correction (the difference between the subjective refraction result and the habitual or presenting glasses) makes sense should be made.

A general rule is that one line of logMAR VA is equivalent to 0.25DS of equivalent sphere where equivalent sphere = sphere + 0.5 [cylinder power].

Although it is useful to measure near VAs, it must be remembered that the typical N-type notation chart is truncated as N5 at 40cm equates to 6/9, so that obtaining N5 does not mean that the patient has the best near VA.

For visions and VAs to be useful, full threshold levels need to be determined. If a patient’s true threshold is 6/5, an error of 0.25DS in prescription (for example an under-correction of 0.25DS in a myope) might not be manifest if the smallest line used is 6/6.

Take care with interpretation of autorefractor results

We found numerous cases where prescriptions were changed, particularly the cylinder, with asymptomatic patients and with no recorded improvement in acuities (see case examples 2, 4, 5 and 6). In addition, some patients had large changes prescribed, which may have been evident from the objective (autorefractor) result, but could not be tolerated by the patient (case examples 7 and 10).

Although an autorefractor offers an accuracy useful for prescription screening,21 this should only be used as an aid to determination of a subjective prescription (figure 5).

Figure 5: Autorefractors are only to be used as an aid to the determination of a subjective prescription

Measure near working distances

As more than twice the number of problems were caused by too high an Addition than too low (9% versus 4%), care needs to be taken with assessment of the required working distance, particularly ensuring it is not too close. When wearing a trial frame in a test room, a patient may hold a reading card closer than they might habitually. This effect is, perhaps, even more so with a phoropter head (figure 6).

We would recommend confirming with a patient where they feel comfortable holding a card and then, with a proposed Addition, ensuring the range of clear vision is equidistant around the chosen point. For example, a patient holds the reading card at 33cm and is then asked to bring the card closer to blur and away to blur. If the near point is much further from the chosen distance than the far point, then the addition is likely a little too strong.

Figure 6: Accurate assessment of habitual reading distances may be difficult with a phoropter head

Use the various prescribing maxims in asymptomatic patients

If a patient is happy with their glasses, has no symptoms, reports good DV and NV and has good VA, then prescribing a change in correction risks making them unhappy.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’, is a very useful rule to use and would avoid about 33% of rechecks.

Don’t change a happy myope

‘Don’t change a happy myope’, is a commonly occurring variant of this, when the myopic patient’s myopia is decreasing and they have no symptoms with their glasses. If there is an improvement in VA in an asymptomatic patient or the decreasing myopia in the ‘happy myope’ is -0.50DS or more, then a change in correction seems warranted. But that change should be small (‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it much’) and, perhaps, just half the subjective change from the habitual correction.

Perhaps more commonly found in practice is the asymptomatic hyperope for whom the subjective refraction yields an increase in their hyperopia. While a small increase in prescription might help these patients, for example with middle distances, prescribing all of the subjective change is only likely to cause problems – 86% of rechecks are from minor changes of 0.50DS or less.

‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it much’, is particularly useful when the patient is happy with their current glasses and has no symptoms, but slightly reduced habitual VAs that are improved with a new correction. In this case, if the maxim ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ is used, it is possible, if not likely, that the patient may develop symptoms a few weeks or months after obtaining the new glasses. In such cases, using ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it much’ and changing the correction slightly is recommended.

Partially prescribe large changes in sphere, cylinder power and/or axis, particularly in older patients

Large changes in prescription have been shown to be associated with an increase in the rate of falls by elderly patients,6 where large changes were defined as follows:

- Sphere changes of ±0.75DS or more

- Increase in cylinder of 0.75DC or more

- Axis change of 10° for a cylinder of less than 0.75DC and 5° for 0.75DC or more

- Any prism change

- Increase in anisometropia of 0.75D or more

Such ‘large’ changes are, perhaps, seen regularly in subjective refractions in practice. However, the likelihood of such changes being only part-prescribed tends to increase with practitioner experience,22 presumably due to prior experience with patient complaints. The importance of part-prescribing such large changes needs to be better appreciated by less experienced practitioners, particularly when considering the increased risk of falls by the elderly, together with increased numbers of reported problems.

Many practices now use an autorefractor to derive the objective prescription and, as described above, the autorefractor result should be considered as an aid to subjective refraction and not a literal indication of what any final prescription should be. Using objective results, whether autorefractor or retinoscopy, the practitioner should aim to change the prescription, particularly cylinders, by the smallest amount that addresses the presenting symptoms and improves VA.

Howell-Duffy et al,22 in a practitioner questionnaire posing five separate patient scenarios, found 84% of respondents were happy to prescribe full subjective changes for -2.50DC of 40° towards the oblique for a 68-year-old and 41% respondents reported being happy to prescribe a -2.00DC increase for a 75-year-old. While these scenarios involve far greater changes than might be found in the ‘real world’, the study illustrated how practitioners might be happy to prescribe very large changes if no consideration of patient adaptation is made and an autorefractor supported such changes.

Ensure recheck patients are seen by an experienced clinician

Almost half of the recheck corrections in our study appeared unsatisfactory and included all the errors seen in the initial prescriptions. The strategy of ensuring a recheck patient returns to see the original clinician means that they will certainly see the number of mistakes made, but is logistically difficult and does not best ensure the patient receives a correct prescription at the recheck.

We recommend that one or more experienced clinicians are chosen to examine recheck patients and the results of the recheck, detailing the cause of the problem, fed back to the initial prescribing clinician so that lessons can be learned. It is crucial that clinicians see the problems caused by their prescribing decisions and are not left to assume that very few problems occur.

Contact rechecked patients after collection of remade spectacles

The traditional assumption following a recheck is that a silent patient is a happy one and so it appears common practice not to contact patients after a recheck lest they should be provoked into reporting more problems. We followed up 161 patients after their recheck and collection of remade spectacles and found 91% of those contacted reported being happy with their new prescription. This supports a policy of following up rechecked patients, for whom a telephone call would represent good patient care and customer service. However, of those we followed up, 5% had a second recheck, 2% were refunded and 1% required further advice and so for such patients a follow-up call could perhaps be considered a last opportunity to retain their loyalty.

- Jeremy Beesley is a Director of Beverley Specsavers, East Riding of Yorkshire and is currently a PhD student at the School of Optometry and Vision Science, University of Bradford, UK.

- David Elliott is the Professor of Clinical Vision Science at the University of Bradford, UK. He is editor of the textbook Clinical Procedures in Primary Eye Care, which is now in its 5th edition and was Editor-in-Chief of the College’s research journal Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics between 2010 and 2020.

References

- Beesley J, Davey CJ, Elliott DB. What are the causes of non-tolerance to new spectacles and how can they be avoided? Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2022;42(3):619–32.

- Bist J, Kaphle D, Marasini S, Kandel H. Spectacle non-tolerance in clinical practice–a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2021;41(3):610–22.

- Confederation O. Optics at a Glance 2014: London: Optical Confederation, 2014. 2015 Oct; https://www.abdo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/optics-at-a-glance-2014.pdf (accessed May 2022).

- Buttle FA. Word of mouth: understanding and managing referral marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing. 1998;6(3):241–54.

- Freeman CE, Evans BJ. Investigation of the causes of non-tolerance to optometric prescriptions for spectacles. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2010;30:1–11.

- Cumming RG, Ivers R, Clemson L, Cullen J, Hayes MF, Tanzer M, et al. Improving vision to prevent falls in frail older people: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(2):175–81.

- Howell-Duffy C, Hrynchak PK, Irving EL, Mouat GS, Elliott DB. Evaluation of the clinical maxim:’If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’. Optometry and Vision Science. 2012;89(1):105–11.

- Arumugam V, Singh S, Ramani KK. Reasons for spectacle reassessment in a tertiary eye care centre over a period of six years. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2018;101(2):237–42.

- Elliott DB, Whitaker D. Clinical contrast sensitivity chart evaluation. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 1992;12(3):275–80.

- Carlson NB, Kurtz D, Hines C. Clinical procedures for ocular examination. Vol. 3. McGraw-Hill New York; 2004.

- Benjamin WJ. Borish’s clinical refraction. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2006.

- Grosvenor TP. Primary care optometry. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007.

- Rosenfield M, Logan N. Optometry: science, techniques and clinical management. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Brookman KE. Refractive management of ametropia. Butterworth-Heinemann Medical; 1996.

- Werner DL, Press LJ. Clinical pearls in refractive care. Butterworth-Heinemann Medical; 2002.

- Milder B, Rubin ML. The fine art of prescribing glasses without making a spectacle of yourself. Triad Publishing Company; 2004.

- Howell-Duffy C, Umar G, Ruparelia N, Elliott DB. What adjustments, if any, do UK optometrists make to the subjective refraction result prior to prescribing? Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2010;30(3):225–39.

- Elliott DB. Clinical Procedures in Primary Eye Care. 5th Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020.

- Read SA, Vincent SJ, Collins MJ. The visual and functional impacts of astigmatism and its clinical management. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2014;34(3):267–94.

- Hrynchak P. Prescribing spectacles: reasons for failure of spectacle lens acceptance. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2006;26(1):111–5.

- Kumar RS, Moe CA, Kumar D, Rackenchath MV, AV SD, Nagaraj S, et al. Accuracy of autorefraction in an adult Indian population. PloS one. 2021;16(5):e0251583.

- Howell-Duffy C, Scally AJ, Elliott DB. Spectacle prescribing II: practitioner experience is linked to the likelihood of suggesting a partial prescription. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2011;31(2):155–67.