A neoplasm is an abnormal new growth of cells which grow more rapidly than normal cells and this can impinge upon and damage adjacent structures. Tumour describes a mass and is a non-specific term for neoplasm.

Cancer is a term usually used to describe a malignant tumour and refers to new growth that has the ability to invade surrounding tissue and spread to different organs, a process described as metastasis.

Cancers are very rarely inherited and most cancers result from changes to genes that can occur through one’s life. Factors that can cause genetic damage include tobacco smoke, X-ray and gamma ray radiation, UV radiation, food substances, toxic chemicals, among many others. There are six main cancer groups:

1 Carcinomas – are cancers that arise from epithelial cells that line the skin, gut, mouth, cervix and airways. Carcinomas make up 85% of all cancers.

2 Sarcomas – are cancers that arise from connective tissue cells such as bone (as in osteosarcoma) or muscles. These make up 1% of all cancer cases.

3 Leukaemias – cancers of the blood with uncontrolled production of white blood cells in the bone marrow. They make up 3% of all cases.

4 Lymphomas – are cancers of the lymph glands, abnormal lymphocytes start to collect in the lymph nodes, bone marrow or spleen. They make up 5% of all tumours.

5 Myelomas – are cancers that affect bone marrow plasma cells which produce immunoglobulin antibodies that fight infection. In myeloma, plasma cells become abnormal and multiply such that they cannot fight infections. Myelomas make up 1% of cancer cases.

6 Brain tumours account for 3% of all cancers and the most common are gliomas.

Primary brain tumours form within the brain as result of abnormal cells multiplying. Secondary tumours result from metastasis of abnormal cells from a malignancy in a different part of the body which establish in the brain.

Symptoms of brain tumour can vary from headaches, seizures, personality changes, visual field defects, vision loss, nerve palsies and focal weaknesses on one side of the body. This article presents two cases that demonstrate the effect of a primary and a secondary brain tumour.

Case 1

Fifty-year-old male patient AC came in for an eye test complaining of dry eyes. Since we did not have an available appointment for four weeks, I suggested that he used Systane eye drops in the meantime.

On the day of the examination the patient reported no benefit from the eye drops and slit-lamp examination revealed a tear break up time of 12 seconds with no punctate staining or dessication on the cornea. The anterior sector appeared normal and healthy as did the posterior retina.

Further questioning revealed the following history.

In 2013 he had suffered a seizure and further tests revealed a glioma of the left parietal-frontal lobe. It was decided to just monitor at this time. However, a year later he experienced transient sharp pain in the right eye followed by what he described as ‘electrical pulses’ down the right side of the body.

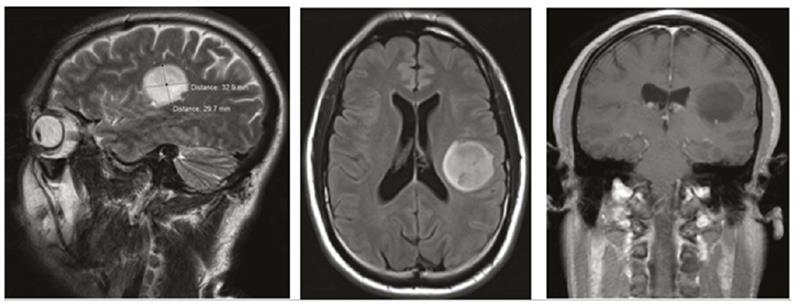

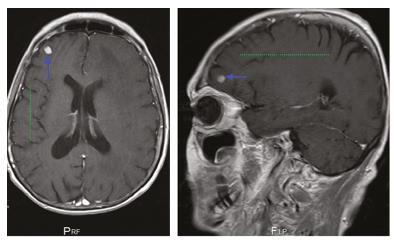

This continued for the next two months so it was decided to have the tumour removed. Figure 1 shows the 3.29cm x 2.97cm round lesion with regular margins and no obvious vasogenic oedema or haemorrhaging. The lateral ventricles seem to be perfectly symmetrical and no displacement of the ventricles can be seen.

Figure 1: Left parietal lobe tumour 3.29cm x 2.97cm, regular and smooth margins seen in transverse, axial and coronal view. Lateral ventricies are not distorted and the brain tissue around is not affected

CyberKnife surgery (a frameless robotic radiosurgery system used for treating benign tumors, malignant tumors and other medical conditions) was performed successfully. Post surgery, the patient had numbness down his right side with 30% improvement three months later.

Now the symptoms were described as a constant electrical tingling from the right forehead down to the legs, and numbness on the right forehead along with a constant feeling of dry eyes. Lesions in the left side of the brain cause symptoms on the contralateral (right) side.

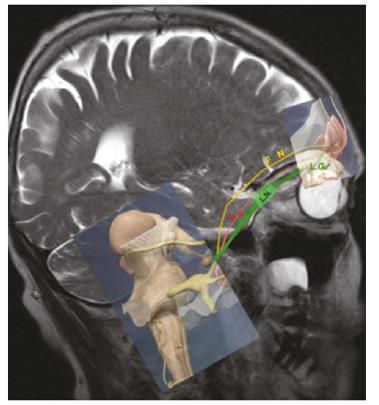

Figure 2: Ophthalmic nerve divides into: Lacrimal nerve (LN) serving the lacrimal gland (LG). Nasociliary nerve (NC) serving the upper nose. Frontal nerve (FN) serving the forehead and eyelid

Management

I decided to refer him back to his neurologist with a diagnosis of possible neuralgia of ophthalmic nerve, V1. The ophthalmic nerve exits the trigeminal ganglion (figure 2) and divides into three branches:

1 Nasociliary nerve which serves the upper nose, lacrimal canaliculi and the medial eyelid.

2 Frontal nerve serving the orbit, central forehead and upper eyelid.

3 Lacrimal nerve serving the lacrimal gland, lateral upper eyelid and conjunctiva.

One can assume that the impact upon the frontal nerve would give rise to the numbness of the right forehead and the impact on the lacrimal nerve would give the sensation of dry eyes.

Facial nerve paralysis (Bell’s palsy) was ruled out as there was no facial drop and no signs of corneal exposure.

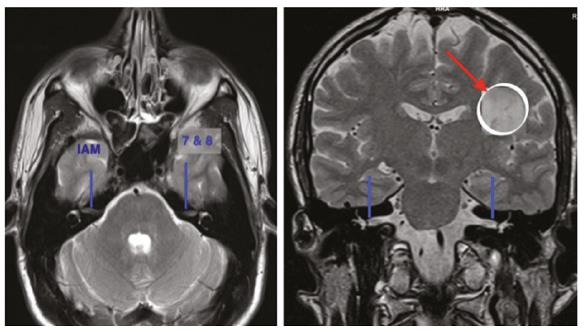

The parietal lobes are involved with sensations such as pressure and pain. A parietal lobe tumour on the left side may give rise to numbness or weakness on the opposite (right) side of the body as experienced by our patient. Other parietal lobe tumour symptoms may include difficulty understanding or speaking words, problems with coordination and seizures (figure 3).

Figure 3: Internal auditory meatus and the 7th and 8th nerve canal are seen (marked in blue). The position of the left frontal-parietal glioma (marked by the red arrow indicating how far it is from the facial or 7th nerveand so not not likely to cause facial palsy or Bell’s palsy)

The neurologist concurred with the findings and decided to prescribe the anti-epileptic drug levetiracetam to reduce the risk of further minimise the symptoms and reduce the risk of further.

Case 2

Seventy-two-year-old female patient was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2014 and had had a partial pneumonectomy (lung lobe removal). She also had chemotherapy initially with carboplatin 390mg followed by vinorelbine 90mg as an adjuvant therapy after surgery to prevent spread of cancer.

Unfortunately, she tested positive for epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) and this meant her treatment was changed to afatinib which blocks EGFR receptors and prevents the cell lung cancer from spreading. There are two types of lung cancers:

- Small cell lung cancers which start in the bronchi near the centre of the chest and metastasise widely. These account for for 10-15% of all lung cancers.

- Non-small cell lung cancers are found in 80-85% of lung cancers and they metastasise more slowly. There are three common types of non-small cell lung cancers: Adenocarcinomas found in the outer lung, squamous cell carcinomas in the centre of the lung next to the bronchus and large cell carcinomas which are found in any part of the lung and grow fastest of all the non-small cell lung cancers.

Ten to 15% of all non-small cell lung cancer patients are positive for epidermal growth factor receptors and these patients benefit from therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitor drug afatinib.

At her eye test in March 2015 a left eye nuclear sclerotic cataract was found giving a visual acuity of 6/18 & N10. She was duly referred to an eye specialist who undertook a left cataract extraction under general anaesthetic on the patient’s insistence. Her lung function was good so the consultant was happy to do the operation under general anaesthetic.

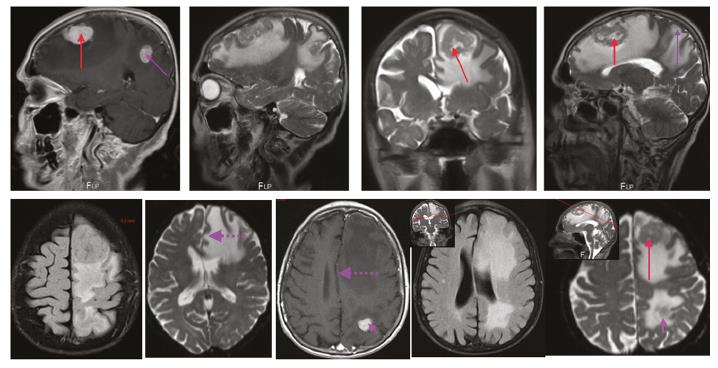

Figure 4: Left frontal lobe tumour 3.4cm x 3.8cm (red arrow) and left parietal lobe tumour 1.24cm x 1.27cm (purple arrow). White and grey patches around the tumour suggests oedema and the dashed dashed purple arrow indicates a midline shift of 1cm. Note the lateral horn ventricles are compressed superiorly by the frontal lobe tumour while the parietal lobe has no such effect

In October 2015 following a routine consultation, her oncologist asked the question ‘Any body problems?’ as the patient and her husband were walking out the door. Her husband mentioned that he found her ‘memory was not as good recently’. Alarm bells rang triggering an immediate brain scan which revealed the following (figures 4 and 5):

- Left frontal lobe large irregular margined tumour measuring 3.4cm x 3.8cm surrounded by a large area of vasogenic oedema encompassing two-thirds to three-quarters of the left frontal lobe.

- A significant midline shift to the tune of 1cm.

- A significant compression of the left lateral ventricle.

- A second metastasised left parietal lobe tumour measuring 1.24cm x 1.27cm, having irregular margins and causing substantial vasogenic oedema in the left parietal lobe.

- The right frontal lobe has a regular bordered and perfectly rounded small tumour with no vasogenic cerebral oedema surrounding the mass.

A diagnosis was made of a left frontal lobe large metastasised secondary neoplasm with surrounding brain tissue swelling leading to lateral ventricle compression and a mid-line shift. A second smaller left parietal lobe (a third the size of the frontal mass) was found also causing brain tissue swelling of the left parietal lobe.

Figure 5: Right frontal lobe contains a perfectly rounded and defined tumour (blue arrow). Note the green line denotes the folds in the cerebral cortex – the gyrus and the depression within the sulcus are clearly visible

A third much smaller regular margined secondary tumour with no obvious effect on the right frontal brain tissue was also found. Frontal lobe function influences memory and thinking and as such this patient had memory issues which her husband noticed.

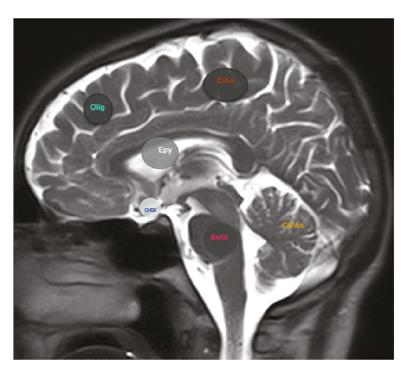

Figure 6: Glial cell tumours:

Olig = Oligodendroglioma in the cerebrum

C/As = Cerebrum astrocytoma

CB/As = Cerebellum astrocytoma

Epy = Ependyoma in lateral ventricle

Bs/GI = Brainstem glioma

O/GI = Optic nerve glioma

Frontal lobe damage also affects personality, causes muscle or body weakness, impairment of sight or speech, loss of inhibitions (swearing), difficulty with planning, loss of smell, unsteady gait, and general apathy. Parietal lobe tumours can affect speech or understanding of what is said, problems with reading or writing and loss of feeling in parts of the body.

Management

On October 26, 2015, the large left frontal lobe tumour, now roughly 4cm in size, was removed by surgery and dexamethasone prescribed to help relieve the significant vasogenic cerebral oedema. Vasogenic cerebral oedema is due to leakage of fluid and protein out of cerebral capillaries into the extracellular space. Because the fluid can flow along fibre tracts, the swelling is greater in the white matter than in gray matter.

On December 5, 2015, the smaller parietal lobe tumour, roughly 1.2cm in size, was given focal ionisation irradiation treatment. The right minute frontal lobe tumour was left untreated and will be monitored to see if it grows and impacts on the brain tissue.

Secondary and primary neoplasms

Secondary brain tumours are due to metastasis. All metastatic tumours are considered malignant and are diagnosed in 170,000 patients per year. The most common metastatic tumours in order of frequency are lung cancers, breast cancers, renal cell cancer, melanoma and colon cancer.

Primary brain tumours have distinct borders and are diagnosed in about 17,000 patients per year of which 3,500 are in people under the age of 20. Incidence increases with age, peaking at the age of 84 years. Two-thirds of primary tumours are non-malignant. Malignant brain tumours spread within the brain and spine but rarely spread to other parts of the body. Primary brain tumours are differentiated into:

1 Meningeal cell tumours.

2 Neuronal cell tumours – rare benign tumours that arise from a group of ganglion-type cells and are more common in children and young females. They are usually located in the temporal lobe and the third ventricles.

3 Schwann cell tumours – occur in cells that coat the peripheral nerves. Schwann cells lay myelin in the peripheral nervous system in the way oligodendrocytes do in the central nervous system.

4 Glial cell tumours. Glial cells (also known as neuroglia), are not nerve cells but form myelin, maintain homeostasis and provide protection and support for neurones in the central and peripheral nervous system. There are four types of glial cells each with associated tumours:

- Astrocytoma – Astrocytes are star like cells in the brain and spinal cord whose major function is to maintain an appropriate chemical environment for neuronal signalling. They transport nutrients to neurones, clean up debris, hold neurones in place, digest dead neurones and regulate content of the extracellular space. Astrocytomas occur in the cerebellum, cerebrum, brainstem, central areas of the brain and the spinal cord.

- Oligodendroglioma – Oligodendrocytes are limited to the central nervous system and lay down laminated, lipid-rich myelin around some but not all axons. Myelin insulates the nerves and facilitates rapid electrical impulse transmission along nerve cells.

- Microglial cells are small cell brain macrophages that remove cellular debris from site of injury. Microglial cells tend to congregate within tumour mass (notably astrocytic gliomas).

- Ependymonas – ependymal cells line the ventricles and central canal of the spinal cord. They function as a barrier between brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and they play a role in CSF balance, toxin metabolism and secretion. Ependymonas account for 9% of all gliomas.

Kirit Patel is an optometrist in independent practice in Radlett, Hertfordshire.