Do monsters have monstrous eyes? While the kraken is (almost certainly) a mythical being, that is not to say that there are not monsters living in the depths of our oceans. And even monsters have eyes; rather large ones, as it turns out. When it comes to eyes, giant squid and their even larger relative, the colossal squid, really do live up to their names. Their eyes are far bigger than those of any other animal, even ones larger than themselves living in the same environment. There are many questions surrounding these mysterious animals, one of which is what they are using their excessively large eyes for.

The kraken; inspired by glimpses of giant or colossal squid?

The kraken; inspired by glimpses of giant or colossal squid?

Of all the animals in the deep oceans, colossal and giant squid are probably surrounded by the most mystery, both in terms of science and in popular culture. Their notoriety must partly stem from Jules Verne’s Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, in which the submarine is violently attacked by something fitting the description of a giant squid. But there are stories going back hundreds of years of entire ships being engulfed by mysterious animals with monstrous tentacles, dragging sailors to their watery graves. However, far from being ship-sinkers or submarine-wreckers, giant and colossal squid are extremely shy creatures that we know very little about. Indeed, despite the best efforts of researchers, there have been relatively few sightings of these incredible creatures. Although they are not exactly the krakens of legend, the idea of a 10m long, 450kg squid with eight arms complete with barbed suckers and two extendable tentacles swimming below the surface of the water is disquieting, no matter how elusive they might prove to be.

Giant and colossal squid are related but separate species of cephalopod (the family that includes squid, cuttlefish and octopus). The giant squid is slightly longer than the colossal squid, at about 10m from the top of the head to the end of the tentacles, but the colossal squid is about twice as heavy, at just under half a tonne. They live most of their lives in the deep ocean at depths of about 1km. We know of their existence from the occasional body washing up on shore, and the very occasional live sighting by fishermen unlucky enough to have their catch pilfered by one of these giants. It was not until 2012 that anyone had ever seen a giant squid behaving in its natural environment. Using an ingenious type of remote camera incorporating a lure that mimics bioluminescent light, researchers were able to capture footage of a giant squid hunting for the first time.

Their diet, which has been determined from examining the stomach contents of the few intact bodies washed ashore, appears to be mostly fish and crustaceans plus the odd giant squid or two. So while they might not be a threat to vessels, giant and colossal squid do pose a threat both to fish and, it would seem, to each other. On the flip side, it appears as though these formidable giants are themselves dinner for an even larger animal; the sperm whale. However, judging by the sucker-shaped scars on the bodies of many sperm whales, the giant squid does not go without a fight. Otherwise, we know very little about the natural history of these animals.

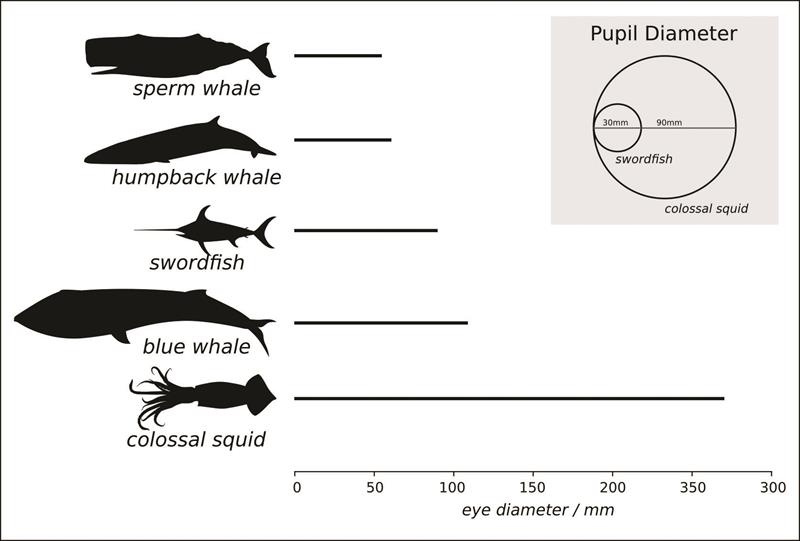

In answer to the question posed at the beginning of this article; do monsters have monstrously large eyes? If we are referring to giant and colossal squid as monsters, then the answer is yes. Their eyes are about 270mm in diameter; roughly the size of a football. The second largest eyes are only 110mm in diameter and belong to the blue whale, an animal more than twice the length and over 300 times heavier than a colossal squid. The below image shows a comparison of the eye diameters of different animals that inhabit the same open ocean habitat as the giant and colossal squid. Their pupil diameter (which is the critical characteristic in terms of optics) is 90mm, three times the next largest pupil diameter, 30mm, belonging to the swordfish. Whales, despite the size of their eyes, have relatively poor vision, which is not surprising given their ability to echolocate accurately over vast distances.

The relative eye diameters of the marine animals with the largest eyes. Despite its relatively small size (silhouettes not to scale), colossal (and giant) squid have eyes almost three times the size of the next largest animal; the blue whale. Inset: the giant and colossal squid pupil diameter is three times the size of the second largest, found in the the swordfish

The relative eye diameters of the marine animals with the largest eyes. Despite its relatively small size (silhouettes not to scale), colossal (and giant) squid have eyes almost three times the size of the next largest animal; the blue whale. Inset: the giant and colossal squid pupil diameter is three times the size of the second largest, found in the the swordfish

Made to measure

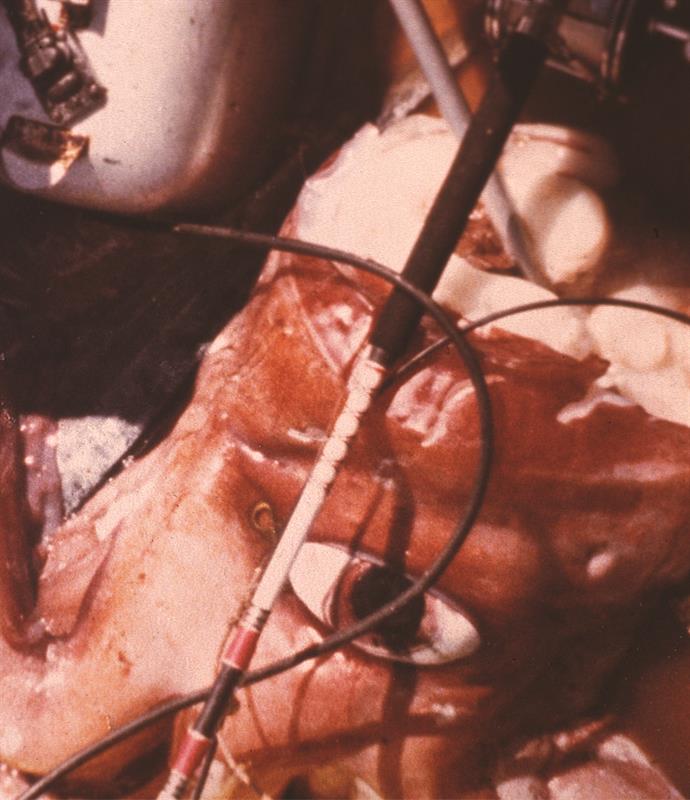

Obtaining accurate measurements for the eye and pupil diameters of giant and colossal squid was far from straightforward. Most of the bodies washed ashore are eyeless – evidently squid eyes are a nutritious meal for other marine life. As regular consumers of squid, octopus and perhaps cuttlefish will know, their bodies have a rubbery texture. Due to this elasticity, it is not possible to tell just from the remaining eye socket how large the eye would have been. Plus without the eye, it is impossible to accurately gauge how large the pupil is. Fortunately, a pair of fishermen who happened to land a giant squid as an enormous bycatch took a photo of it in the boat. This image is unlikely to win any prizes for artistry, given there was a fuel hose lying across the primary subject. However, the presence of this unsightly hose, which has standard dimensions, allowed researchers to accurately measure the dimensions of the eye. Shortly after this image surfaced, so did the body of an intact colossal squid in waters off the coast of New Zealand. Measurements of the fresh eyes of this specimen tallied with the photographic measurements. The eyes of giant and colossal squid are the largest eyes on earth, being nearly three times bigger than the next largest. This excessively large eye adds to the mystery of the giant and colossal squid.

The freshly caught head of a giant squid, caught on February 10, 1981 by fisherman Henry Olsen and the picture was taken by Ernie Choy. The standard fuel hose lying across the eye is a standard size, and was used to measure the diameter of both eye and pupil

The freshly caught head of a giant squid, caught on February 10, 1981 by fisherman Henry Olsen and the picture was taken by Ernie Choy. The standard fuel hose lying across the eye is a standard size, and was used to measure the diameter of both eye and pupil

Why, exactly, do they need eyes three times as large as animals living in a similar habitat? Or to flip the question on its head, why do other animals not have larger eyes. It is not simply a limitation due to the size of skeleton; blue whales are far larger than colossal squid and even the head of a swordfish, though smaller than giant squid, could theoretically house a much larger eye than the one they have. As I have discussed in previous articles, larger eyes are more sensitive to light, as they are able to capture more photons. It would therefore follow that animals living in the relative darkness of depths of 1km would have enormous eyes. In the open ocean, animals can spot objects, such as potential prey or predators, either by their dark silhouette against the slightly brighter background of the surrounding water (figure a below), or from underneath, backlit by the skylight above. Or, they may be indirectly detectable due to bioluminescence, light produced by marine organisms using chemical reactions. Their aim is to either startle their potential predator with the sudden flash of light, or to draw the attention of an even larger predator (there is always a bigger fish) to scare away their attacker. An animal could detect another either by seeing the whole of its body lit up by bioluminescence (figure b), or by detecting individual bioluminescent spots (figure c). But there are limits on how large an eye can be.

The three strategies for visual detection: (a) dark object against bright background, (b) bright bioluminesent cloud against darker background or (c) by individual bioluminescent events

The three strategies for visual detection: (a) dark object against bright background, (b) bright bioluminesent cloud against darker background or (c) by individual bioluminescent events

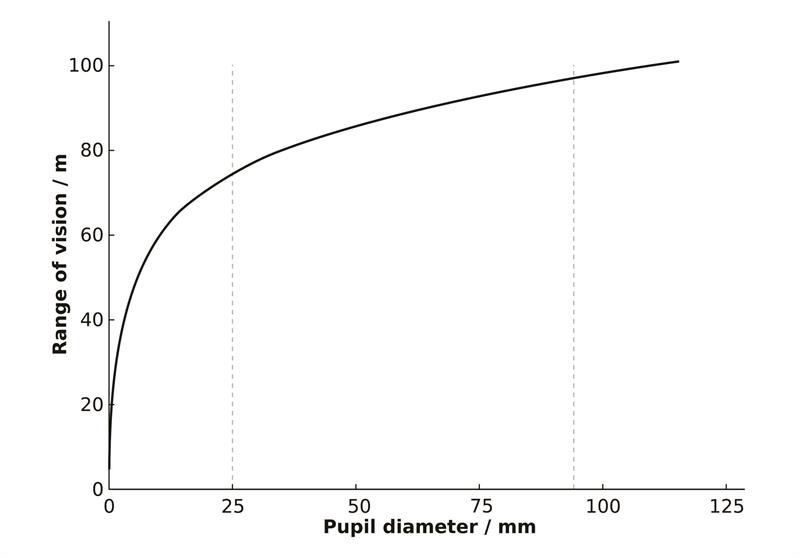

One potential limitation on eye size is the energetic cost of the eye. A larger eye has a much larger metabolic cost both in terms of maintaining the anatomy and increased neural processing. The other limitation is the aquatic environment that these animals live in. Unlike on land, the range of sight (often referred to as the ‘visibility’ by divers) is limited by absorption and scattering in the water. Even in crystal clear water, the visibility is less than through the air on a misty day. An animal’s range of sight can be improved by increasing the size of an eye, but only up to a point. Increasing the pupil diameter gives significantly better range up to about 25mm but as the eye gets bigger, the relative increase in the viewing distance does not increase as much. In other words, viewing range and eye diameter in the aquatic world follows the law of diminishing returns. Given that eyes are costly energy-wise, we would not expect to see eyes with a pupil much above 25mm, and indeed the swordfish (which has the second largest pupil size, despite blue whales having a larger eye diameter) has a max pupil diameter of 30mm. This is in contrast to giant and colossal squid, which have pupils three times that large. So why do these giants have such enormous eyes?

Detection strategy

In terms of an animal’s fitness, a simple, linear detection distance probably is not the best measure. In the open ocean, where attack can come from any direction (above and from below), a better measure would be the entire volume of water they can monitor. We also need to consider the ‘detection strategy’ that the animals are using. As stated earlier, there are three types of visual detection possible (figure 5): viewing the object as a dark silhouette against a brighter background, as a bright region against a darker background due to a cloud of bioluminescence, or by detecting individual bioluminescent ‘events’. The performance of each of these strategies, ie the volume of space they allow an animal in open water to monitor, will depend on a number of factors including the water depth, the size of the target the animals are detecting and the size of the animal’s pupil. Using mathematical modelling, it is possible to find the optimum strategy for a range of tasks for an eye with specific characteristics.

In the case of giant and colossal squid, with pupil sizes of 90mm living at a depth of about 600m, they have three possible relevant targets for detection: predators (sperm whales, larger than themselves), other giant or colossal squid (their own size, important for mating) and prey (fish, smaller than themselves). The results of the modelling show their huge eyes are optimised for spotting large predators via the clouds of bioluminescence they elicit when swimming. For all other tasks, smaller eyes (of similar size to those of swordfish) perform just as well. Clearly, for these giants, their chief concern, and the main evolutionary driver of their visual system is the early detection of sperm whales, their main predator. From these findings, we can infer that giant and colossal squid are most likely ambush predators, remaining relatively stationary in the water column waiting for prey to come close, all the while on the lookout for the faintest glimmer of bioluminescent light that is the calling card of a patrolling sperm whale. Once spotted, the squid can then take evasive action to avoid the approaching whale.

This work is an interesting example of how visual modelling can give us an insight into an animal’s visual behaviour and their lifestyle. Normally, in order to understand an animal’s visual ecology, researchers make use of observations of an animal in its natural environment before carefully designing and running experiments in the laboratory before drawing conclusions. In the case of giant and colossal squid, where live sightings are extremely rare and incredibly fleeting, this methodology just is not possible. Indeed, it is hard to imagine a lab capable of mimicking the natural conditions of these giants! Using these same modelling techniques, it is possible to infer the lifestyle and behaviour of extinct animals, such as the ichthyosaur, a prehistoric marine reptile similar to modern-day dolphins, which had eyes of a similar size to giant and colossal squid.

By studying the extraordinary eyes of giant and colossal squid, we are able to shed light on how these elusive animals live, as well as glimpsing the behaviour of animals long disappeared from our oceans.