The human binocular system has a reflex desire for heterophoria and when using a 'normal' viewing environment the binocular lock will hide small vertical phorias. The effort required in maintaining compensation may cause significant visual symptoms, argues Tony Nixon. It may also be a factor in reduced reading abilities

It is known that the human visual system is highly sensitive to small misalignments evidenced by the accuracy of vernier acuity. However, this same sensitivity may also be a source of visual symptoms, particularly if the binocular fields are misaligned vertically by only a small amount.

Some researchers suggest reduced visual functions when the perceived images come from misaligned eyes. Hubel and Weisel (reported by Solomons)1 showed a reduced cortical binocular receptor cell response with induced ocular phoria in cats. Tunnicliffe and Williams2 reported reduced binocular contrast sensitivity and Jenkins et al3 reported reduced binocular acuity associated with small phorias.

Dowley4 suggests a strong binocular adaptive process because of the statistically high numbers of heterophoric subjects. Henson and North5 showed a reflex adaptive procedure to induced vertical and horizontal phorias. This evidence suggests that accurate and stable retinal alignment of the overlapping binocular fields is the desired state of the binocular system. Where undue effort is required to maintain this state there may be an adverse influence on visual comfort, visual and psycho-visual functions and possibly learning abilities.

Evans6 in work with dyslexic children refers to binocular instability and likens the symptoms to uncompensated heterophoria. Stein et al7 at Oxford University also working with dyslexia writes about 'visual instability' and 'stable eye fixation' as having links with learning abilities and lists similar visual symptoms. Adler and Grant8 on work on the aetiology of reading difficulties suggest treatment of binocular instability may be beneficial. In the US, Garzia,9 estimates that 20 per cent of the adult population has marked difficulty with everyday reading tasks.

Current optometric investigation of phoria compensation is performed in as normal a viewing situation as possible, namely in minimising any interference with binocular control.

The evidence suggests that the desire for alignment in a normal viewing environment might not reveal small discrepancies and show a compensated position. A fixation disparity test asks if the binocular vision is able to compensate for a phoria but does not indicate the latent phoria for which compensation is required. Only by dissociating the two eyes is the amount of phoria revealed and hence the clue to how much adjustment is required to maintain compensation.

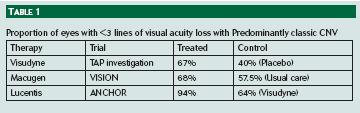

Observations by the author suggest a symptom pattern that relates to an apparently compensated vertical phoria as shown in Table 1. Other researchers suggest similar patterns of symptoms. Roy and Yolton10 list 23 different symptoms which they suggest are associated with latent vertical phorias. A similar list of symptoms and signs is given by Eskridge11 in his work on vertical muscle adaptation. Stein12 also indicates a similar pattern of symptoms in his work on developmental dyslexia and lists visual symptoms including 'letters blur, visual discomfort, glare and losing place'. Pickwell13 gives a similar list of symptoms for a decompensated heterophoria. Garzia9 suggests a pattern of signs and symptoms for 'reading eye movement disorder' which also corresponds with parts of the pattern of symptoms in Table 1. The terms 'eye strain' or 'asthenopia' might also include a similar symptom pattern. This symptom pattern may often be associated with concentrated visual tasks at any viewing distance.

Clinical Investigations

Measuring the vertical phoria was undertaken using a Maddox rod at both distance and near. The technique was altered in that the measurement was first made with the Maddox rod in front of the right eye using prisms to align in front of the Maddox rod. This was then repeated with the Maddox rod in front of the left eye. This technique often reveals a different amount of deviation in each eye and correction of this difference with a prism as little as 0.5D can give relief to the symptom pattern. This was done as a routine part of normal examinations. Investigation showed that it was not important which eye was tested first. Results showed reasonable correlation with 74.5 per cent showing identical measurements whichever eye was measured first.

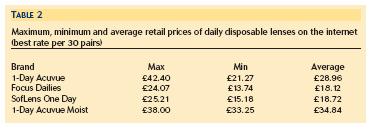

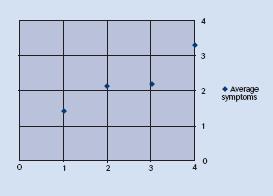

The most notable observation was that there was often a different measurement from each eye. Using a simple pointing technique to check for a dominant or reference eye it was shown that the larger deviation often corresponded with the non-dominant eye, see Table 2. Based on the work by Henson and North, a number of subjects showing all or parts of the symptom pattern were given an adaptation test by inducing a vertical phoria and re-measuring the phoria three minutes later. The levels of adaptability were allocated as 1, identical phoria measurements as before inducement, 2, induced fixation disparity, 3, as 2 but with different Maddox rod measurements and 4, inability to achieve fusion. The degree of symptoms seemed to be closely related to the ability to adapt to the induced phoria, see Figure 1.

Reading Difficulty

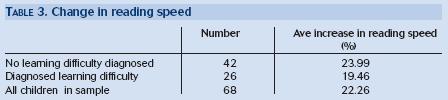

Children who present with apparent difficulty with reading and writing skills may often show symptoms as in Table 1. Careful assessment of the vertical phorias with reference to handedness and ocular dominance is significant in deciding in front of which eye to place the correcting prism. Correction of as little as 0.5 prism dioptre vertical was found to give better convergence, more comfortable vision and increased reading speed. (Assessed using the Wilkins Rate of Reading Test14) Although not empirical, many parents report back much improved performance and greater self confidence in these children. Table 3 shows results from a random group of children seen by the author.(All had minimal hyperopic refractive error: average age 9.47 years: 38 per cent diagnosed as having specific learning difficulty.)

At a neurological level, several authors suggest some deficit in the magnocellular pathways may contribute to reduced visual and perceptual performance. Stein has investigated the role of the magnocellular pathway in relation to poor readers and concludes that 'language, reading, spelling, attentional and coordination problems may all result from an impaired development of magnocellular neurones in the brain: these are specialised for tracking transients, visual, auditory and motor'.12

Hurst, in suggesting a Model of Visual Balances, concludes that there are links and interdependencies between functions of processing visual information, oculomotor control and fusion as part of the balance between parvo and magnocellular pathways.15

Summary

There is a pattern of signs and symptoms which relate to an apparently compensated vertical phoria. The innate desire for alignment and the adaptability of the human visual system enables the eyes to appear fully compensated for vertical phorias when examined using binocular tests designed for a 'natural' viewing environment, for example fixation disparity tests.

Due to strong ocular dominance, a small vertical phoria might also be controlled when using the Maddox rod test but may be revealed if the phoria is measured separately for each eye. The visual symptom pattern relates to misalignment across the whole binocular field and not specifically to macular alignment and therefore may also apply to some unilateral amblyopes. Correction of this differential prism, even if only small, may relieve the symptom pattern. The same investigative technique and correction for children with reading difficulties can give increases in reading speed in the order of 20 per cent whether or not there are diagnosed specific learning difficulties.

As a guide, the amount of prism to be prescribed is the difference between the two eyes with base direction the same as the greater measurement. This will mean that the prism is normally put in front of the non-dominant eye.

References

1 Solomons H. Binocular Vision Heineman, 1978, London 6-2-86.

2 Tunnicliffe and Williams () The effect of vertical differential prism on binocular contrast sensitivity function, Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 1985; Vol 5 No 4.

3 Jenkins TCA, Abd-Manan F, Pardhan S, Murgatroyd RN. () Effect of fixation disparity on distance binocular acuity Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 1994; vol 14 no 2 p131.

4 Dowley. Orthophorisation of heterophorias. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 1987 Vol 7 No2.

5 Henson DB and North R. Adaptation to prism induced heterophoria. American Journal of Optometry and Physiological optics, 1980; 57:127-137).

6 Evans BJW 2001 Dyslexia and Vision, Whurr Publishers 2001 pp43-44.

7 Stein J,Talcott and Witton. The sensorimotor basis of developmental dyslexia, Chapter 2, Dyslexia: Theory and Good Practice, 2001. Edited by Angela Fawcett, Whurr Publishers.

8 Adler P and Grant R. Literacy Skills and Visual Anomalies, Optometry Today, 1988; Vol. 28 No1.

9 Garzia RP. Vision and Reading, 1996 Mosby p11.

10 Roy and Yolton. Use of monocular occlusion to assess latent vertical imbalance. Problems in Optometry, 1992; Vol4 No4 December.

11 Eskridge J Boyd. Vertical Muscle Adaptation Problems in Optometry, 1992; Vol 4 No4.

12 Stein J. Genetic and neural basis for dyslexia; Powerpoint Presentation, Department of Psychology, University of Oxford (Accessed July 2001).

13 Pickwell D. Binocular Visual Anomolies. Butterworths, 1984, p65.

14 Wilkins. Rate of Reading Test Wilkins, Jeanes, Pumfrey and Laskier, 1996. MRC Applied Psychology Unit, Cambridge CB2 2EF (Available from the Institute of Optometry, 56-62 Newington Causeway, London SE1 6DS).

15 Hurst. The Hurst Model of Visual Balances Optometry Today, 2004; Vol 44 No 3 p 40.

Tony Nixon is an optometrist working in private practice