The Khmer Sight Foundation (KSF) is a new charity founded by the late Dr Kim Frumar, an Australian ophthalmologist, and Sean Ngu, the Cambodian Secretary of State.

It aims to deliver and build sustainable eye care for the people of Cambodia by undertaking charitable ophthalmic missions as well as training local eye care professionals. International teams from the UK, France, Germany, Singapore and India will visit Cambodia over the next four and a half months to undertake weeklong missions. These teams consist of volunteer consultant ophthalmic surgeons, fellows, junior doctors and optometrists.

The missions are held in a modern hospital in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. Cambodia has a population of 15 million people of whom 180,000 are blind. Ninety per cent of these cases are due to either preventable or reversible causes.

Cataract is the leading cause of blindness and there is currently an estimated backlog of 300,000 patients requiring cataract operations. Cambodia has one of the lowest ophthalmologist per capita figures of any country in the world, with only 32 specialists to serve its entire population.

A lot of this is due to the recent Pol Pot regime of the 1970s in which 21% of the population, the majority of whom were educated individuals, was murdered. Though this regime officially ended in the 1990s, the impact is far reaching.

Cambodia also lacks the basic infrastructure to manage this epidemic of eye disease. KSF, in association with the Cambodian government, is currently building a new ophthalmology centre in Phnom Penh. This will consist of a school of optometry and centre of postgraduate ophthalmic training to undertake population screening and be the location of future KSF missions.

The mission runs with the goodwill of volunteers ¬ both international and local. The local volunteers, often Cambodian medical students, work extremely hard as translators, scrub nurses and everything in between.

The patients and clinical cases

Eighty-five per cent of the population lives in rural provinces. KSF, with the help of local volunteers, undertakes rural population screening throughout the year. Those earning less than $100 USD per month are eligible for the programme.

Local medical volunteers identify any patients with potentially treatable eye conditions. KSF then arranges transport from the provinces to Phnom Penh on specific days. Each day, a coach of new patients from a new province arrives at the hospital centre. These patients are then seen in clinic by the international team of the week. This clinic team is composed of optometrists and ophthalmologists who work side by side. If any uncertainty arises over a patient’s condition, there are senior ophthalmologists on hand for discussion.

Patients present with a wide range of conditions. As would be expected, many have evidence of cataract. Due to the nature of the mission, only those with significant cataract or pterygium affecting their visual acuity were eligible for operations.

A lot of unusual cases were encountered. In Cambodia, congenital defects pose an economic burden to the families and there are no specific low vision or blindness services available to children born with these conditions. Recently, a baby with a cleft palate had been rescued after being found buried alive by their father. A young mother brought her three-month-old child to hospital, concerned that the child was not visually responsive.

In fact, the child had been born with bilateral anophthalmia (absence of eyes), unbeknown to the mother (figure 1). This tragic condition had to be explained to the mother. For safeguarding reasons, the police had to be involved to visit the family regularly and ensure no harm came to the child.

Figure 2: A young boy with congenital glaucoma

There were several cases of congenital glaucoma (figures 2 and 3). An ophthalmologist had never seen the children before; thus the glaucoma had resulted in buphthalmic eyes and corneal opacities.

Figure 3: A young boy with congenital glaucoma

Another interesting case was that of an 11-year old girl with a cataract (figure 4). The patient was seen in clinic and was suitable for theatre.

Figure 4: A young girl with cataract with Professor Sunil Shah

However, once the cataract was extracted, a retinal detachment and toxocara scar were visualised. This meant that the girl would never recover her vision. Nonetheless, the patient and her family were extremely grateful for the help they received.

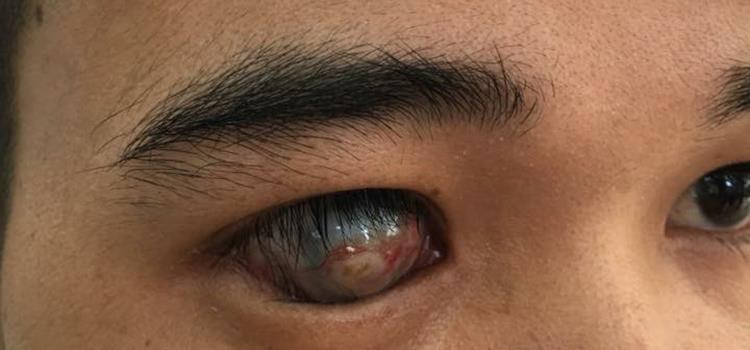

Several patients presented with hand movements vision secondary to corneal scarring from agricultural injury (figure 5). There was nothing that could be done and unfortunately this had to be broken to the patients in a gentle manner.

Figure 5: A young man with a corneal scar

There were patients who presented with ophthalmic manifestations of other diseases. One male attended with what clinically appeared to be thyroid eye disease (figure 6).

Figure 6: A man with thyroid eye disease

Another 21-year old woman attended with cataracts, Cushingoid features (figure 7) and elevated blood pressure – features suspicious of congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Figure 7: A patient with cataract and Cushingoid features

A man attended with unilateral proptosis (figures 8 and 9) and brought his CT scans with him. On these, a brain tumour was evident.

Figure 8: A man with unilateral proptosis

Figure 9: The proptosed eye

He was unable to afford the life-saving treatment he needed. A lady presented with a non-healing wound. She had developed a mole on her lower lid and had used a plant thorn to remove it at home. This was suspicious of a skin cancer (figure 10). The pathology of these patients was outside what KSF could offer. However, they were referred to local specialist services by the team for further investigation and management.

Figure 10: A lady with a non-healing wound

In total more than 400 patients were seen in clinic and 200 received operations. Gratitude from patients was ubiquitous. Patients from the provinces sometimes left their homes 24 hours in advance to camp at the bus stop from where KSF would collect them. They were eager to be seen and to receive help that could potentially change their lives.

Post-operative patients would sleep in the hospital and be seen the next morning for review. Each evening the team would wave goodbye to a corridor full of smiling, eye-patched patients and each morning the clinic team would review the next happy patients, grateful to be on the road to recovery.

How you can help

KSF is able to work through the good will of volunteers and is constantly in need of optometrists to join the missions. Regardless of your area of clinical practice or expertise, enthusiastic and skilled optometrists provide invaluable support.

The team is housed in comfortable, 4-star hotel accommodation with air conditioning and good facilities. The days are long and the work is intense; however the atmosphere is good spirited and everyone works well in a team towards a united goal. Evenings are spent unwinding together, mulling over the day’s events. There is limited time for tourist activities and a few days extra is recommended for visiting Cambodia’s many historical sights.

Volunteering for the KSF is an incredibly rewarding way to use your skills in optometry to help patients in need. If you would like to get involved, please email sunil.shah@khmersight.com.

Dr Priyanka Mandal is a specialty doctor, Patrick Gunn a senior optometrist and Professor Sunil Shah is a consultant