Case 1

Seventy-eight-year-old male type 2 diabetic TL rang for an emergency appointment, having experienced mistiness in front of the right eye on waking. The day before, he had experienced a jagged pattern in front of the right eye accompanied by a thumping headache. Of much more of a concern to his wife had been an incident a week earlier when he had become disorientated in a local car park, having forgotten where the car was parked and appearing lost as to what action to take. His wife felt that he was in this state of confusion for about an hour or so and has consulted his GP immediately who undertook blood tests as well as blood pressure checks. All the tests came up normal.

Current medication: Metformin for diabetes, bisoprolol for heart, lipitor for cholesterol, indapamide and losartan for blood pressure, and warfarin as an anti-coagulent. He had suffered a heart attack a year ago and had been fitted with a stent — hence all the heart and blood thinning medication.

Refraction:

(6/9) R. +1.50DS / -1.25 X 100 (6/7.5) ADD +2.50DS (N5)

(6/9) L. +1.75DS / -1.75 X 100 (6/7.5) ADD +2.50DS (N5)

Ocular examination:

- Bilateral clear intraocular implants.

- Intraocular pressures normal R and L 19mmHg.

- Left retina showing no optic disc, vascular or macular abnormalities.

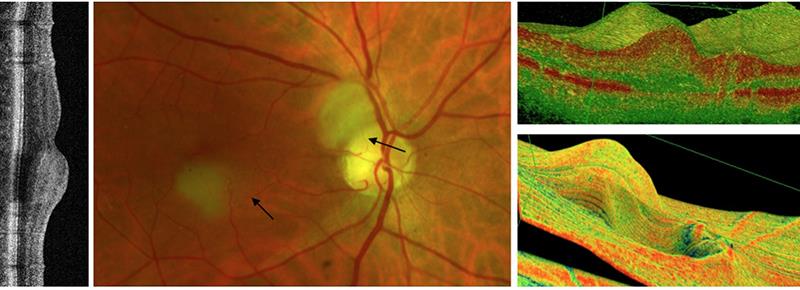

- Right optic disc revealed a superior swelling — what appeared to be a large circular white patch of retinal oedema or infarct but no obvious central retinal or branch retinal artery occlusion (figure 1).

- Inferior to the macula another triangular whitish patch of retinal oedema or infarct but no obvious sign of branch retinal artery occlusion (figure 1).

- Rest of the retina appeared healthy.

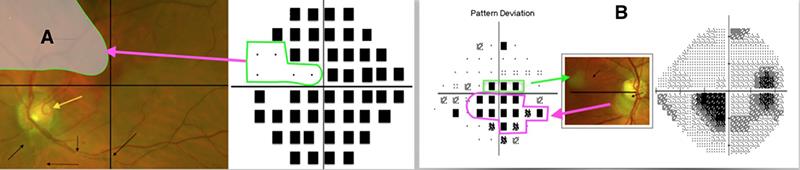

- Visual field showed no scotoma in the left eye.

- Right eye 24-2 Visual field revealed an enlarged blind spot and an inferior scotoma from the blind spot. Another definite scotoma appeared superior to the macula mimicking the infarct inferior to the macula (see figure 4B).

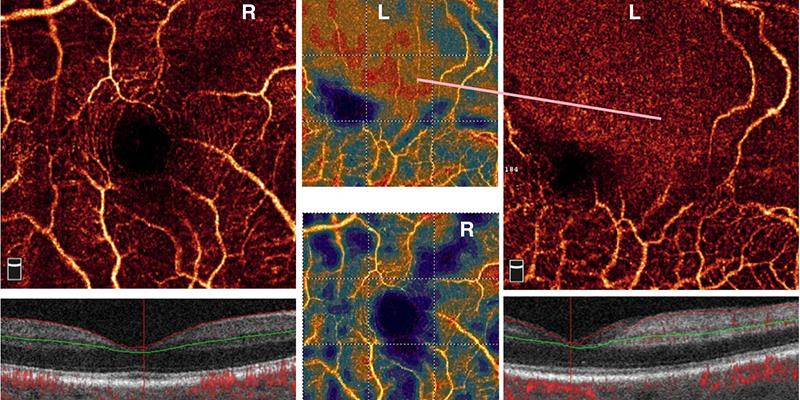

Figure 1: Central image showing the cilioretinal artery occlusion (superior branch) causing an infarct of the retina as seen clearly on the right side of the OCT scan. Also, there is a temporal cilioretinal artery occlusion causing an infarct inferior to the macula which is clearly seen on the left side of the OCT scan where inner to outer swelling is visible

Diagnosis

A tentative diagnosis of retinal infarct superior to the optic disc and inferior to the macula and most likely to be a rare occurrence of cilioretinal artery occlusion. No obvious emboli were seen and looking closely at the cilioretinal arteries it appeared that these tiny arteries were the most obvious culprits.

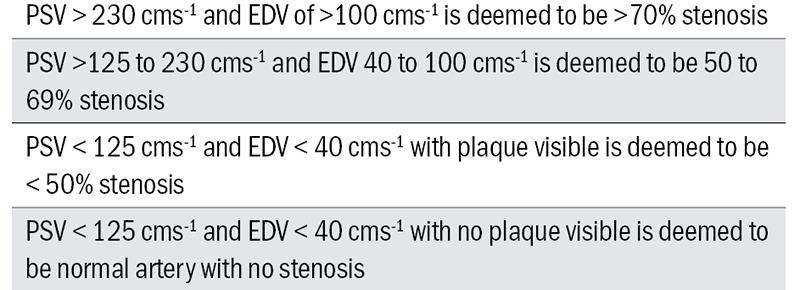

Table 1: Ultrasound grading of stenosis

A letter was written to his general practitioner to refer the patient to a neurologist to rule out a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or stroke bearing his mind his memory lapse a week earlier.

Neurological conclusion

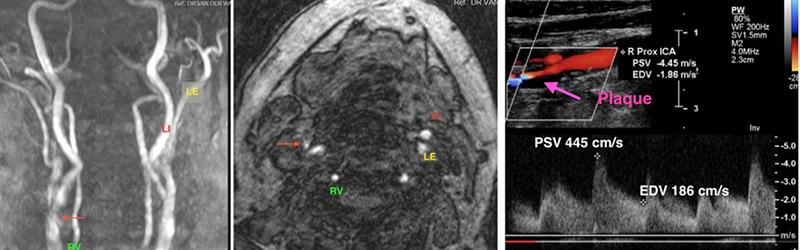

All the tests for internal or common carotid artery stenosis and cerebral stroke were negative. His blood tests were all negative and no signs of giant cell arteritis. Ultrasound showing patent internal carotid, external carotid, common carotid and vertebral arteries (figure 2).

Figure 2: Central MRI scan (middle) surrounded by Doppler ultrasound scans of various vessels. The Doppler scans suggest no stenosis of any artery. Peak systolic velocities (PSV) are less than 125 cms-1 and end diastolic velocities (ED) are less than 40 cms-1 and this confirms no stenosis

The neurologist concluded that this patient suffered transient global amnesia and concurred with my findings of possible cilioretinal artery occlusion for which there was no treatment and did not merit ophthalmologist investigations. No further treatment was necessary and the patient was referred back into community care.

Case 2

Seventy-five-year-old JC’s wife rang to say she was bringing her husband to the practice straight away as he had noticed loss of vision in the left eye about three hours earlier. He was seen immediately in between regular patients and further questioning revealed that he had a tiny patch of vision in the outside corner of his left eye and there was painless loss with no signs of flashing lights or floaters. There was no temporal pain or feeling of malaise and no jaw claudication. His last eye examination was at the practice 9 months previously with no change in his spectacle prescription and having an acuity of 6/12 & N6 each eye due to early incipient cataracts.

Current medication: Gabapentin, amlodipine, bisoprolol, atorvastatin, morphine and co-codamol.

Optometric examination:

- Right eye unchanged spectacle prescription of -3.75DS / -1.25DC X 90 ( 6/12 & N6 unaided)

- Right eye no pupil defect abnormalities - direct, convergent or near reflex.

- Left eye vision was hand movements only.

- Left eye afferent pupil defect.

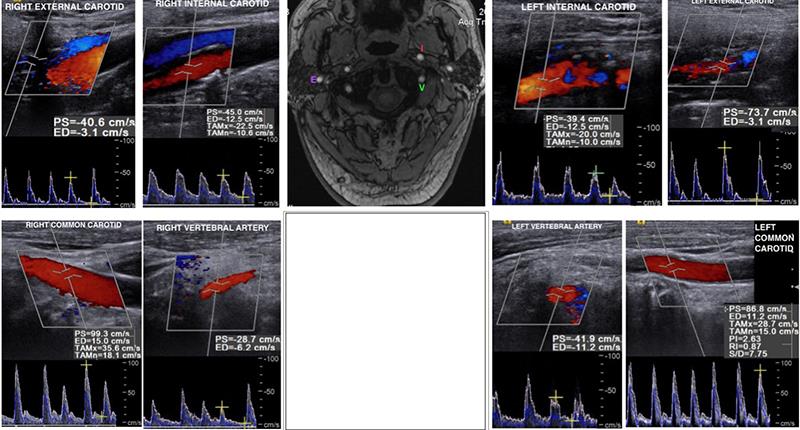

- Ophthalmoscopy revealed ‘cattle tracking within the superior temporal, superior nasal and inferior temporal arteries< (figure 3).

- Superior nasal, superior temporal and inferior temporal retina revealed white retina indicating an infarct of the retina.

- Small portion of the nasal left retina was unaffected and this corresponded to the patch of vision that the patient had – a diagram of what the patient saw was plotted (figure 4A).

Figure 3: Black arrows depicting emboli sites within arteries and the position of cattle-trucking of blood within the vessels. White areas represent the infarct or oedema of the retina (CRAO). Yellow arrow indicates the cilioretinal artery supplying blood to the local area

The patient had multiple emboli of his left central artery leading to the ‘cattle tracking’ of blood in the artery. In essence he was told he had left eye central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO). With such a large array of emboli’s he was sent to his general practitioner with an important note that he be referred to the stroke unit as this was a stroke of the eye and there would be a high chance that he may suffer a brain stroke. Unfortunately, for the patient he was referred to the local eye clinic and had to endure the same tests that were undertaken at the practice. He was told he would be seen at the clinic in six weeks’ time and discharged.

Figure 4b: Cilioretinal occlusion with an inferior infarct to the macula and superior to the optic disc. The retinal image has been inverted and the defect above the macula is seen in green while the optic disc infarct is seen in pink

Dismayed, they rang the practice to say how could they pursue this further. I could only say that they should push the doctor to see if he could try and get him to the stroke unit. Unfortunately, three weeks after his diagnosis of CRAO he suffered a stroke with loss of speech and left-sided paralysis. He was seen urgently at the stroke unit at last and a diagnosis of 80% right and left carotid artery blockage. Immediate action was taken to do a bilateral carotid artery endartectomy (arterial stent). No scans were forthcoming so I have enclosed scans and ultrasound for a patient with a narrowed right carotid artery.

Transient global amnesia

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a sudden attack of transient loss of memory for recent events and an impaired ability to retain new information. Transient global amnesia is a solitary event and the symptoms last less than 24 hours, after which the amnesia improves, although patients may be left with a distinct lapse of recollection for events during the attack. There is a demonstrated association between transient global amnesia and migraines but rarely patients with TGA complain of an associated headache.

Patients with TGA have intact visual-spatial and social skills. Language function is also preserved. No obvious pathopathology is found with TGA and positron emission tomography (PET) and diffusion weighted MRI (DWI) scans have made inferences to transient disruption of blood flow to areas that involve memory such as the thalamus, amygdala and hippocampus. Precipitating factors include emotional stress, physical exertion, pain, cold water exposure, sexual intercourse and Valsalva manoeuvre and this would be related to increased venous return to the superior vena cava. The back pressure in the jugular venous system probably disrupts intracranial arterial flow with venous ischemia to memory areas in the brain.

TGA is an innocuous condition with no lasting cerebrovascular or neurological damage and the prognosis is much better than TIA’s. TGA diagnosis is made on the basis of the the following signs and symptoms:

- Sudden onset of memory loss.

- Retention of personal identity.

- Recognise familiar faces and objects and able to follow simple instructions.

- No paralysis of limbs.

- No evidence of seizures.

- Common features involve repetitive questioning eg ‘What am I doing here’ or ‘How did I get here?’

Cilioretinal artery occlusion and central retinal artery occlusion

Cilioretinal artery is seen in approximately 14% of the population and the prevalence of cilioretinal artery occlusion is rare one in 10,000 to one in 100,000. It is not a medical emergency. In 10% of patients cilioretinal artery supply the fovea directly and these patients with acute CRAO attack would achieve good central visual acuity.

Figure 5: Right capillary network clearly seen around the macula superiorly and inferiorly. There are some blue areas which may represent ageing due to cataract. The left capillary network is not seen superiorly and it appears that the retina is devoid of any vessels. Due to the infarct, there is a patch of red seen on the vessel density plot

Understanding the anatomy is important. Ophthalmic artery is the 1st intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery. In the orbit the ophthalmic artery branches into the central retinal artery, posterior ciliary arteries and muscular branches. The short posterior ciliary arteries supply directly to the choroid and occasionally there is an anatomical variation of the short posterior artery called the cilioretinal artery which provide ciliary circulation blood supply to the retina. Hence occlusion of the cilioretinal artery can occur without the central retinal artery being affected.

Figure 6: Right internal carotid stenosis (red arrow). There is no stenosis of the left internal carotid (LI), left external carotid (LE), left vertebral, right external carotid and right vertebral arteries. Ultrasound flow rates for the right internal carotid artery are PSV of 445 cms-1 and EDV of 186 cms-1.

Central retinal artery occlusion appears as a sudden painless loss of vision in one eye caused by embolic blockage of the central retinal artery. The consequences of these are a inner retinal layer oedema and ganglion cell pyknosis (necrosis of cell nuclei). The fovea assumes a cherry red spot due to the intact retinal pigment epithelium and underlying choroid as the fovea is nourished by the choriocapillaris. The oedematous retinal nerve fibres resolve within six to eight weeks and the end stage appearance is a disc pallor and attenuated retinal arteries.

Figure 5 shows OCT angiography for a case of cilioretinal artery occlusion and figure 6 and table 1 show ultrasound scanning for stenosis.

Kirit Patel is an optometrist in independent practice in Radlett, Hertfordshire.