When it comes to memorable names in optics, Oliver Goldsmith stands out from the rest.

Some would say it is so memorable because the company has maintained the ability to sell high quality products and services for such a long time – and they would be right. But without a piece of advice given to the company’s founder, Philip Goldsmith, nearly 100 years ago, history could have been very different.

In 1919, Philip Goldsmith was a salesman for well-known Hatton Garden optical firm, Raphaels. He drove a van that was used as a mobile showroom and generally sold the company’s sight testing products to jewellers who stocked frames and lenses. Goldsmith’s boss saw something in the salesman and sensed he wanted to go it alone. He said that if he ever did set up a company, he should drop the Philip part of his name and call it Oliver Goldsmith, so that it would be more recognisable and a play on the Irish poet of the same name.

Seven years later, Goldsmith started his own firm and as his former boss suggested, dropped the Philip and named the company P. Oliver Goldsmith. Attracted to the higher end of the of optical goods sector, Goldsmith began by making spectacles from tortoiseshell, which the current incumbent of the Oliver Goldsmith name (Andrew Goldsmith) says has a buttery smooth feeling that no other frame material can match.

Tortoiseshell was an expensive choice for patients, but there were ways of making it more accessible. Shell from the tortoise’s belly was the most desirable and expensive option, as it was not affected by sunlight. The side of the shell was a cheaper option, with the bark section from the top even cheaper still. Imitation shell plastic spectacles were another contemporary option, and both were preferable to the highly flammable nitrate that was widely used at the time.

In Japan, demand for nitrate frames has, unbelievably, started to grow again. The material is much harder than regular acetate and as a result, can be polished to a higher standard. ‘The opticians over there know the dangers and are happy to dispense them, but it’s not something that will come over here,’ jokes Goldsmith.

The first location of the business was the top floor of a building in Poland Street, London. He built up a team of craftsmen at the company and they soon set about producing shell and imitation shell, but Goldsmith had doubts over the aesthetics of the imitation material.

Believing an alternative would be well-received, he set about working alongside a plastics producer to create a material coloured in such a way that it would blend in with the skin. The resulting frame was named Dawn, because it marked the beginning of a new era not just for the company in the 1920s, but in how glasses were received.

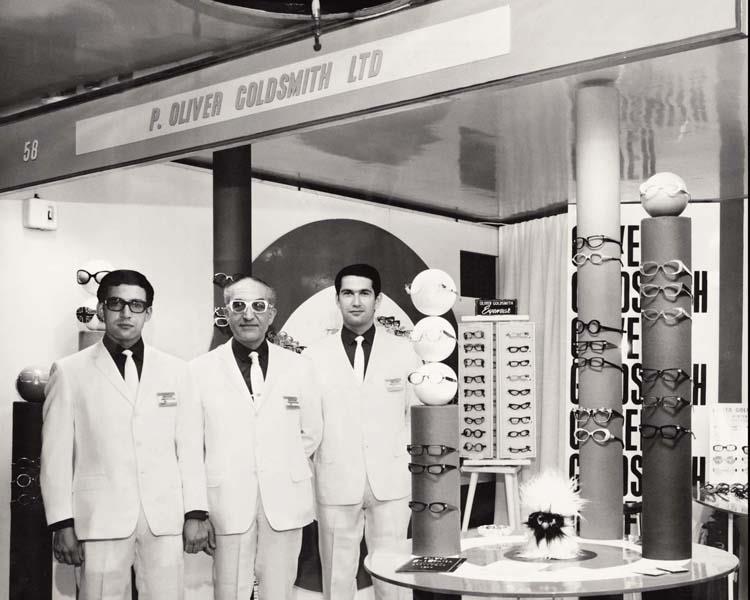

All white on the night – the Goldsmiths at an exhibition

In World War Two, Oliver Goldsmith was seconded to the government to make prescription glasses for the armed forces. ‘My grandfather said the most distressing aspect of work at the time was getting the “dead list” who no longer needed spectacles made for them,’ says Oliver Goldsmith.

The firm still produced glasses, but form was not as important as function. The gas mask spectacle was in great demand at the time – with ultra-thin temples and small diameter lenses.

Two years after the war, Oliver (Philip)Goldsmith died suddenly, having kept a health condition secret from his family. His son, Charles Goldsmith, who had worked at the company since the age of 16, assumed the name Oliver when he took over the business.

Succession was never part of the founder’s thoughts, but by the time his son came to take the reins, the company was well established. When Oliver Goldsmith (Charles) and his wife had children, one of which being Andrew Goldsmith, they would be given the middle name Oliver, which Andrew later assumed. Oliver Goldsmith’s daughter, Alex, has been given the middle name Olivia, so that famous name could well have a different slant in future.

At the beginning of his tenure in the early 1950s, Goldsmith wanted to bring sunglasses into the consciousness of the public. At the time, sunglass production was fairly primitive, with opticians replacing spectacle lenses with tinted sun lenses. Goldsmith thought this practice could be bettered, so designed what he felt were some better looking frames and took them to Fortnum & Mason and Simpsons, where they were very well-received by affluent shoppers.

Eric Morecambe wearing the Mike frame named after a friend of Oliver Goldsmith

Publicity was the key driver for the company at the time, and this meant extravagant designs that would capture the imagination of fashion magazines like Vogue, Tatler and Harpers & Queen – who would also go on to commission special pieces. Fashion designers soon came knocking at Goldsmith’s door, wanting him to design extra special sunglasses for their fashion shows, but there were occasions when the sunglasses received more publicity than the clothes.

Long live Oliver Goldsmith

Goldsmith (Andrew) began his career at the age of 16. He did not attend university, but instead was sent by his parents to a finishing school in Geneva. His desire was to be an architect, but he says his maths was not up to scratch.

‘There was a tendency to enter the family business in the ’50s, but my father didn’t push me or my brother into it. Instead, I approached him and said “architecture isn’t working out, can I be a frame designer?”

‘He agreed and on my first day, I asked him where the design room was. “No, no, no,” he said, telling me I had do a five-year apprenticeship first.’

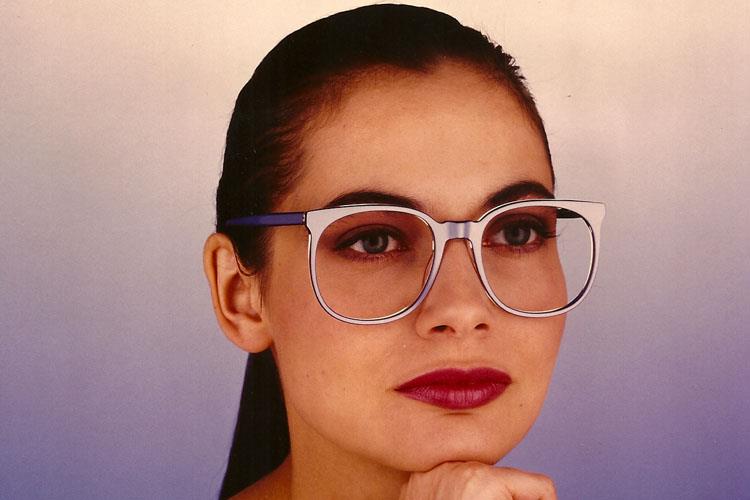

The Photograph collection, the first to be released with Fabris Lane

He was tasked with the company’s menial jobs at first, but was soon trained in design and frame making. Frame sales was another area which Goldsmith had to experience. In the ’60s, without the communication media we know today, Goldsmith was forced to make lists of potential clients and was not allowed to call in advance because long-distance call charges were too expensive. He would have to drive to his destinations, consult the phone directory to find the locations of practices and then drop in announced with ‘a smile on my face’.

In 1965, as the swinging sixties hit its stride and Carnaby Street was in its pomp with the likes of Vidal Sassoon and Mary Quant in residence, Goldsmith (pictured left) was promoted to run the business overseen by his father. In the period where fashion rules were thrown out of the window, the stigma around wearing glasses quickly disappeared, playing right into Goldsmith’s hands.

Goldsmith’s first spectacle frame design was named Rip and a chance encounter at the firm’s premises with Lord Snowdon and Arthur Askey paved the way.

‘Lord Snowdon looked through all of father’s designs but eventually chose Rip,’ says Goldsmith. A picture of Lord Snowdon judging a glassware competition appeared in the papers, which not only gave the firm publicity but bolstered Goldsmith’s reputation as a designer in his own right.

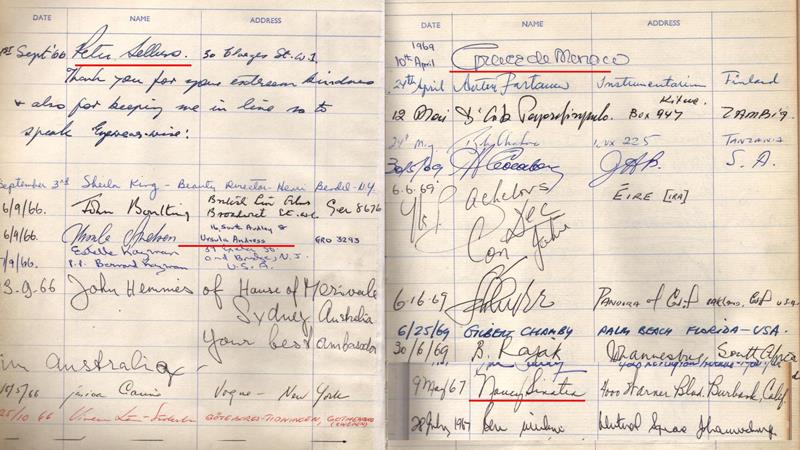

The Annette from the early 1970s named after an American lady Goldsmith met on his travels

During the course of the 1960s, Oliver Goldsmith’s stock grew even more with a slew of famous wearers. Peter Sellers, Audrey Hepburn, Nancy Sinatra, Peter Lawford, Michael Caine, Diana Dors and John Lennon were just a selection of famous names to wear the designer’s glasses, many finding their way on to film and TV screens. Special frames were later created for Caine in his film work and Audrey Hepburn donned a one off frame in Two For the Road.

Princess Grace of Monaco was probably the biggest Oliver Goldsmith aficionado, with 45 pairs of glasses. She was also the only member of a royal family to endorse the brand.

Possibly the most famous wearer of Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses was the Princess of Wales. ‘When she was thinking about marrying the Prince of Wales, my father seized the opportunity for a piece of PR and quickly got some frames to her before she went on a trip to Australia. We wouldn’t have been able to say she was wearing them, but those in the opticians’ trade would know,’ says Goldsmith.

The 90th anniversary limited edition version of the President

The frames unfortunately arrived after she left, but when she returned, she wrote a hand-written letter to Oliver Goldsmith thanking him for the glasses and that she would be wearing them in future having decided to marry Prince Charles.

Goldsmith continued to design frames for Princess Diana, but her lady-in-waiting suggested a different approach. The company was briefed on her various trips and the outfits she would be wearing so that matching frames could be produced.

‘It was exciting seeing the frames on the cover of magazines like Women’s Own – it sent a tingle down my spine,’ recalls Goldsmith.

The Ajax frame from the mid-70s

Goldsmith was presented with the opportunity to meet the princess in the ’80s while on a flight from Tokyo to London. ‘I was in the business class section of the flight sitting next to the boss of Suzuki Motorsport and mentioned to him that I made her glasses,’ he says. ‘He didn’t believe me and said I should go and say hello to her if my story was true. I went to the restroom and said to myself, “if you don’t do this now you’ll never get the chance again”.

‘So as I walked back I gave my card to her lady-in-waiting who was sitting next to her and explained that I made the princess’s glasses. We had a brief conversation for about 30 seconds, but I was so embarrassed that it felt like a lifetime.’

A handful of the famous names in the Goldsmith ledger including Peter Sellers, Ursula Andress, Princess Grace of Monaco and Nancy Sinatra

Having designed for Princess Diana, Goldsmith has also approached Prince William in recent years, offering to make frames for him. The prince said he was touched by Goldsmith’s offer and would be in touch should the need arise.

A parting of ways

In 1989, the company was split into two divisions – ophthalmic and sunglasses. ‘My brother Ray and I just couldn’t work together anymore. We had different views on how the company should be run and who exactly should be “Oliver”,’ says Goldsmith. Goldsmith says he wanted the ophthalmic frame side of the business and brother Ray wanted the sunglasses. A short time later, Ray passed away and Oliver was too busy to reintroduce sunglasses, so it went into hibernation. In 2004, Ray’s daughter, Claire Goldsmith approached Oliver to ask if she could reintroduce Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses to the market in memory of her father. Claire has now established a successful brand which iconic Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses are recreated and her own line of ophthalmic frames, CG Claire Goldsmith, takes on a more modern aesthetic. ‘The businesses run parallel with each other, but people often ask why we don’t work together and I have to explain that it’s potential conflicts of various licensing operations I have around the world that prevent this from happening. She has done very well and I’m pleased for her,’ he says.

Philip Oliver Goldsmith with his mobile showroom and driver in the 1920s

Oliver has maintained the spectacles side of the business and now has licensing operations in the US, Europe and Japan, and in 2015 signing an agreement with Fabris Lane for production of a new range for the UK market.

To celebrate the firm’s 90th anniversary, Goldsmith says he wanted to create a really special limited edition frame, which has led to an updated version of the President being produced. ‘We have added metal inlays on the fronts and the side, which have first been plated with a layer of palladium, then a layer of 24 carat gold. This has been repeated with the hinges,’ says Goldsmith. The frame will be completed with special inscriptions and details. Orders for the leather-covered box set have been flooding in already, with one practice ordering six – including one for himself and one for a patient who has not even seen them.

The Oona frame named after a saleslady in Harrods who was selling Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses

The limited edition model is sure to appeal to the dedicated band of Oliver Goldsmith followers around the world. ‘The Japanese and Taiwanese collectors are certainly the most dedicated. This box set is something that will really appeal to them and will only go up in value,’ says Goldsmith.

The future

It would be easy to assume with the Fabris Lane licensing deal, Goldsmith would have one eye on slowing down. Optician asked if this was the case and received this forthright response: ‘I have no intention of slowing down. I have been suffering with a bad back recently so that has physically slowed me down, but that will be better soon and I’ll be back to normal. Retiring now would drive me mad.’

Sunglasses like Jester were created to drive publicity in magazines like Vogue

Indeed, Goldsmith has eyes on utilising 3D printing techniques and incorporating them into the Oliver Goldsmith range.

It is this willingness to embrace change and adaptable nature that has kept the Oliver Goldsmith business running for 90 years. Through world wars, economic depressions and periods of huge cultural change, Oliver Goldsmith has found the knack of embracing change without having to reinvent itself. The centenary plans have already started.

Optician would like to thank the Clothworkers’ Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion department for hosting the interview. Access to the Oliver Goldsmith collections is by appointment, booked in advance through its dedicated email address clothworkers@vam.ac.uk.