My concept of time seems to have taken a hit over the past couple of years. This was most apparent a few Sundays ago as I drove to Telford on a bright Sunday morning to attend the College of Optometrists Optometry Tomorrow conference, the flagship CPD meeting making a welcome return as a live event after an enforced absence. It seemed way more than two years since it last took place here, when the main concern was whether the Severn might break its banks and halt proceedings. How little were we aware of what was about to be unleashed just days after the 2020 conference.

Though much of the conference was also being live streamed, more than 550 delegates opted instead to attend in person and were treated to two days of top quality lectures, workshops and seminars. In this first review, I will focus on the morning session of the first day, which included two lectures of particular interest in my view, as they looked at two completely different but important areas of neuro-optometry.

Emergency Neuro-Ophthalmology

It is always reassuring to hear that your local secondary care ophthalmology team is in tune with optometry and able to give appropriate feedback to help ensure the best patient care and use of clinic time. So, I was pleased to see my local A&E consultant neuro-ophthalmologist, Rhys Harrison (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust), open the lecture track with a presentation focusing on the recognition of neurological disease that might warrant emergency referral (figure 1). As expected, much of the lecture looked at the careful assessment of swollen optic discs.

Any health assessment upon which a management decision is based must always begin with a careful history-taking. Key areas to cover are as follows:

- Age; inflammatory conditions may present younger than cardiovascular disease complications

- Past medical history; previous cardiovascular risk factors or autoimmune disease must be established, as well as

- any history of malignant disease

- Laterality; the nature of the visual pathway helps to locate disease. Unilateral vision loss is likely to come from ocular or optic nerve disease, while bilateral loss may be chiasmal or post-chiasmal, especially where there is visual loss respecting the vertical midline

- Speed of onset; the onset of vision loss through vascular disease takes just seconds or minutes, inflammatory disease more likely hours or days, while loss through compressive lesions may take days to weeks

- Pain; pain on eye movement may indicate retrobulbar or orbital disease, while the location of headaches may help differentiate intracranial lesions from asthenopic or postural influences

- Past episodes; any previous episodes are of significance

After listing some characteristic symptoms of diseases such as optic neuritis and giant cell arteritis, Harrison then listed the key examination tests for neurological disease as vision, colour vision, pupils, visual fields and disc assessment. Gross colour assessment was, he said, often useful and might be a simple confrontation test using whatever was to hand. Presenting the bright red tropicamide Minims box to each side of the patient might pick up red desaturation, for example.

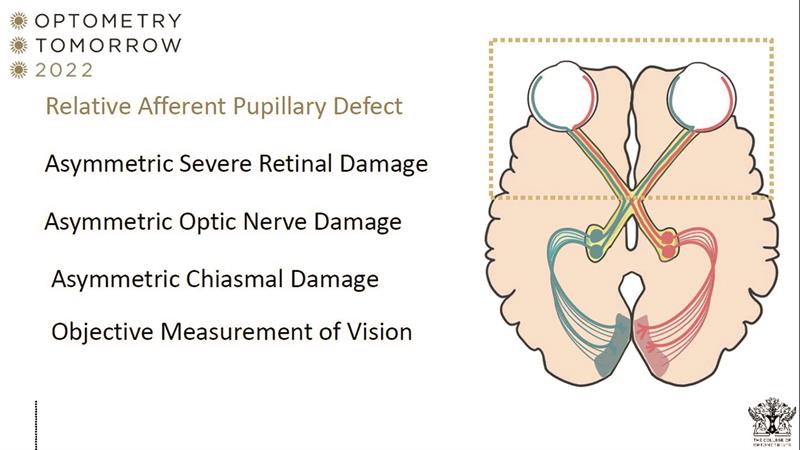

Pupil assessment, being an objective test of nerve function, is essential. A relative afferent pupillary defect is expected with any asymmetric severe retinal damage, asymmetric optic nerve damage or asymmetric chiasmal damage (figure 2).

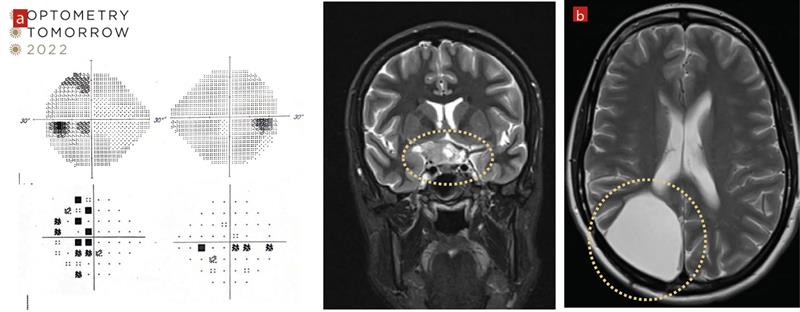

Harrison then used a number of clinical cases to illustrate how the nature of field loss was able to inform subsequent head scans in locating intracranial lesions impacting upon the visual pathway (figure 3).

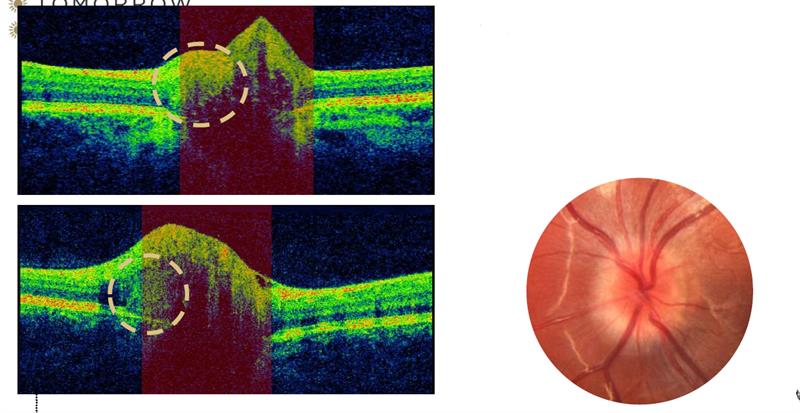

Much of the remaining lecture dealt with disc analysis, perhaps not too surprising since the increased awareness of the potential consequences of papilloedema in recent years. Most of the audience had access to OCT disc scanning and quite a few also had fundus autofluorescence; something the speaker felt was a major advance for the primary care community in assessing swollen-looking discs. With apparent disc swelling, obscuration of blood vessels is a key observation to look out for.

One recently introduced concept when assessing a swollen-looking disc is the presence of PHOMS. Peripapillary hyper-reflective ovoid mass-like structures (PHOMS) are homogenous rounded structures that were traditionally considered as a subtype of optic disc drusen (figure 4, pictured below; PHOMS seen on OCT scan (left) and fundoscopy (right) . However, PHOMS are now considered to be different to disc drusen in that they:

- Are hyper-reflective without a sharp outer margin or hyporeflective core

- Often lie external to and surrounding large parts of the disc

- Do not autofluoresce

- Are not visible on B-scan ultrasound despite their superficial location

- May be seen in patients with papilloedema without optic disc drusen

This was a useful lecture, and one all the more reassuring in that it showed ophthalmologists fully aware of the clinical and technical capabilities of the primary care optometry community.

Charles Bonnet Syndrome

I was very keen to hear the talk from Professor Mariya Moosajee (of Moorfields Eye Hospital and the Francis Crick Institute) looking at the latest understanding of Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS), something that we come across in low vision clinic on a daily basis and which, if ignored, can cause considerable distress for a patient.

First described by Charles Bonnet, an 18th century philosopher who recounted his grandfather’s hallucinatory experiences upon losing vision, CBS is defined as ‘visual hallucinations which occur when individuals are losing their sight.’ Importantly, it is not a mental health issue.

CBS can occur with any eye disease and at any age, the risk increasing with the extent of sight loss. Though a prevalence of some 30% in those with sight loss is often quoted, the figure may be much higher and is likely to remain unknown due to the concerns of sufferers in reporting their symptoms. There is no auditory, smell or touch component; this is important to remember when confirming any hallucination as being CBS.

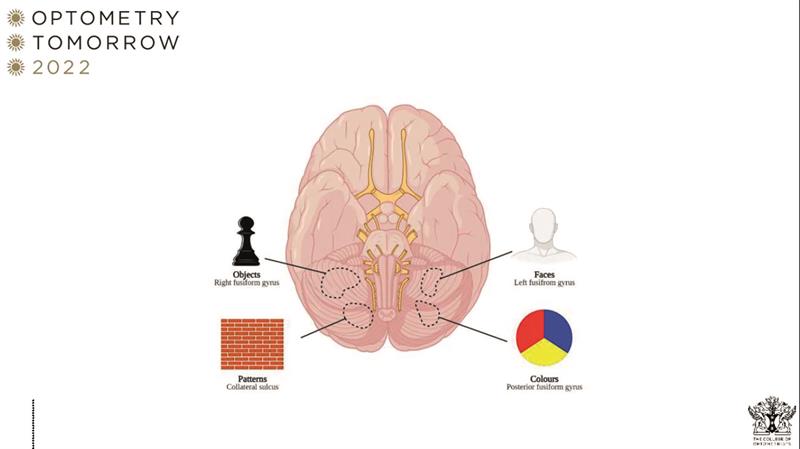

The hallucination may take many forms, from geometric shapes and patterns (simple CBS) or detailed visions of people, objects or landscapes (complex CBS). Indeed, the nature of the image is linked with the area of the brain that is stimulated to respond to the sight loss (figure 5; the nature of the image is related to the area of the brain that is excited in response to sight loss).

Professor Moosajee emphasised the importance of referring CBS to a GP for a full physical examination to ensure there is no acute delirium or psychotic component, and perhaps for dementia screening for elderly patients. Importantly, some systemic medicines known to trigger or exacerbate hallucinatory events might need review. These include the commonly prescribed anti-acid drug lansoprazole, which is known to trigger CBS, as well as tricyclic antidepressants and synthetic opiates. Where CBS causes significant distress, psychiatric intervention may be warranted, though it is important to remember that many patients, with good support, reassurance and information, may embrace their hallucinations and sometimes even enjoy their colour and vividness.

Of the many studies cited during this excellent lecture, I would draw your attention to one recently published paper that has shown that around half of respondents in a survey experienced some degree of exacerbation of their CBS visual hallucinations during the Covid-19 pandemic.1 This may partly be explained by increased loneliness and/or environmental triggers to which all of us were subjected during lockdown.

References

- Jones L, Ditzel-Finn L, Potts J, et al. Exacerbation of visual hallucinations in Charles Bonnet syndrome due to the social implications of COVID-19. BMJ Open Ophthalmology, 2021;6:e000670