I qualified just as there was a long-awaited review of the general policy to refer everything. I still remember the old adage, ‘when in doubt – refer’ being passed on to me, mantra-like. As sensible as this might sound, it did tend to encourage defensive behaviours in some who tended to use it as a cover to hide from any further investigation and reasoned decision as to whether a referral might be appropriate and, if so, for what purpose and with what urgency.

With the rise in independent prescribing, coincident with the need to reduce pressure upon secondary care services, I now believe that the new mantra should be ‘when in doubt, look again’. An awful lot can then be managed with good advice or with an appropriate intervention from a suitably qualified and experienced eye care professional (ECP) colleague within primary care.

During the lockdown period, many of us were sent images of anterior and external lesions by patients, sometimes with a brief symptom list, and forced to decide upon a diagnosis and management. The most common lesions were easy to identify, for example the subconjunctival haemorrhage in figure 1, where reassurance was key along with ascertaining the likely cause (such as sneezing) while ruling out any potential systemic association, as might be suspected with recurrence in someone at risk of as-yet undetected cardiovascular health concerns.

Others, such as the chalazia in figure 2, could be offered advice remotely with the aim of reviewing in practice at a later date. In cases where a benign lesion was likely, such as the lid naevus in figure 3, the quality of the photograph dictated whether to see in practice or review in three months for re-imaging. Sometimes, immediate practice review was warranted, as with the infiltrative keratitis in figure 4 (infiltrates marked by white arrows) to rule out ulceration or anterior chamber activity. In only a very few cases, such as an obvious rolled-edged and ulcerated basal cell carcinoma (BCC) in figure 5, was referral without further review warranted.

However, only a fool would always be confident about their decisions to refer or self-manage these common conditions. A recent webinar, organised by DOCET, gave a timely reminder of what to look for when reviewing the very many ways lid lumps and bumps can present in practice and to help refine decision-making before referring or managing. Renowned consultant ophthalmologist Mr Raman Malhotra managed a comprehensive review of both benign and malignant eyelid lesions, summarising key features, diagnosis, management and referral of the conditions by primary care ECPs. I feel more confident having participated. Here are a few key points I took from the session.

Chalazia

Mr Malhotra initially focused on the most common benign eyelid lesions, explaining the distinction between a hordeolum; the latter being an infection of a gland, such as a stye, as opposed to a chalazion, which is an inflammatory response within a gland, typically the meibomian gland.

Having established the lump to be a chalazion, hot compresses and massaging are the first line of management; ‘at least once, but ideally two or three times a day.’ It is, however, important to look at any underlying predisposing factors. Rosacea, poor diet and overall poor health are all know to have an association, and managing these is essential in both treatment and reducing recurrence. I know this as, until I tackled my rosacea with oral tetracyclines, I suffered recurrent chalazia throughout my 30s.

Topical steroids, not antibiotics, might aid treatment when initial approaches fail as they may address the inflammatory cause. Fluorometholone (tds for two weeks) is the recommended treatment as it has poor ocular absorption and so minimal adverse effects, but this intervention is only needed if the chalazion does not respond to initial compress/massage management.

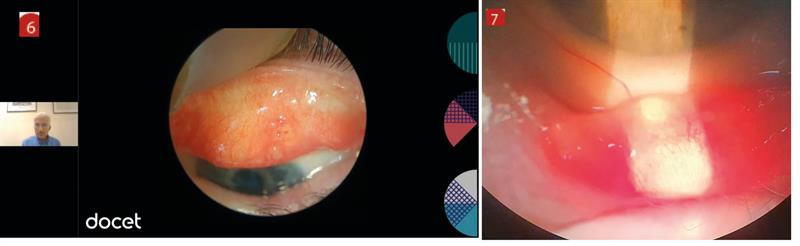

After showing a more typical chalazion (figure 6), Malhotra then showed some less identifiable examples (figure 7) to remind us all of the need for careful examination at all times. In South East Asians with an upper eye lid chalazion, a sebaceous carcinoma needs to be excluded, so referral is appropriate. Also, while chalazia may cause telangiectasia and lash loss and so be misidentified as a BCC, they are usually focused around the anterior lamella (AL). Extension of a BCC to the AL is much rarer and usually accompanied by destruction of the local architecture.

Most important point; lid eversion is essential for examination.

Benign or Malignant

Key symptoms that might suggest malignancy are:

- Progressive: continuing increases in size are always suspicious.

- Resistant: resisted any previous treatment

- Painless

- Bleeding

Key signs are:

- Hard and firm to the touch, and not tender

- Loss of lashes

- Distortion of the normal architecture; this might be an ectropion

- ‘Pearly’

- Scarring in the absence of traumatic history

Central ulceration is a useful indication of active growth, suggesting that the cells are growing faster than the blood supply can cope with, resulting in ulceration. Similarly, telangiectasia indicates rapid growth resulting in a build-up of VEGF in an attempt to vascularise the new tissue.

A good illustration of this is the amelanotic lid naevus in figure 8. Lashes can clearly be seen growing from the lesion, there is no localised tissue disruption and the lesion is longstanding. Best monitored, not referred.

Cysts of Zeiss and, as in figure 9, Moll might easily be misidentified as a BCC. However, on palpation, if it feels soft and not hard, and there is no destruction of tissue at the base; cyst of Moll is most likely. Wherever there is lash loss, a biopsy might be undertaken to confirm the lesion identity.

Milia are common after abrasion or sunburn and do not need intervention (figure 10). Xanthelasma, figure 11, are worth further assessment for raised cholesterol levels.

Molluscum contagiosum is a viral condition and often presents with a secondary follicular conjunctivitis. Key to management is to remove the central core, where the viral matter is concentrated, and the secondary infection should then resolve.

Actinic or solar keratosis, commonly found in older, pale skinned people who have been exposed to sunlight (figure 12, left), has a 1% potential for malignancy so should not be ignored when present on sun-exposed areas. Interestingly, there is good evidence for the usefulness of oral nicotinamide (vitamin B3) supplements, available from health food shops. Indeed, if a patient has had more than one BCC, this supplement is also recommended as a useful prophylactic measure.

Pigmented Eyelid Lesions

A useful mnemonic to remember when looking at pigmented lesions of the lid. Suspicion should be aroused by:

A) Asymmetry

B) Border irregularity

C) Colour variation

D) Diameter greater than 6mm

E) Evolving lesions

Other things to look out for include bleeding or oozing, itching or pain, and swelling beyond the borders. I also like Malhotra’s ‘ugly duckling’ sign; is the lesion out of place compared with its surroundings? If so, be suspicious.

Basal and Squamous cell Carcinoma

BCC is the commonest lid malignancy: 55% inferior to eye, 25% nasal, 15% superior and 5% temporal. A lovely example of differential diagnosis was then presented, reminding all not just of the importance of looking for the signs mentioned above, but also of the variability in appearance of BCCs.

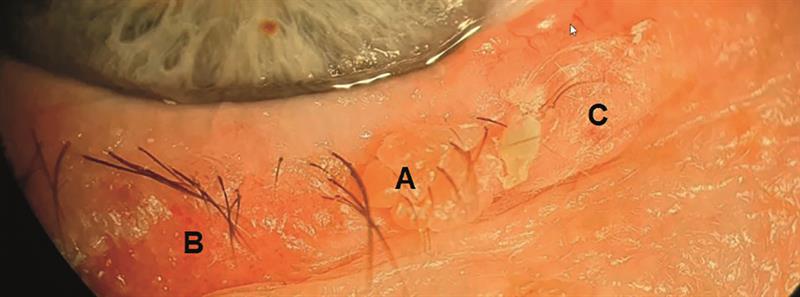

In figure 13, pictured right, Malhotra was not worried by the papilloma marked ‘A’, as it had lashes growing from it and no localised disruption. ‘B’ is an area of actinic keratosis (red and flat), while ‘C’ shows lash loss, extension onto posterior lamella. ‘C’ was later confirmed to be a BCC. While BCCs sometimes cause minimal surface impact, internal extension may require significant surgical removal of tissue.

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the second commonest lid malignancy (the most common in Asia) and, as they metastasise, can prove fatal if ignored. Again, presentation can be very variable so the key signs and symptoms must always be considered during examination. One useful fact here; they occur most commonly after organ transplantation.

Finally, Malhotra calls the sebaceous carcinoma ‘the great masquerader’ as it mimics a persistent chalazia. In an Asian, any suspect malignancy or persistent chalazion of the upper lid must be considered a sebaceous carcinoma unless proved otherwise.

Refer or Monitor

Melanoma is a two-week referral, as well as for SCC and sebaceous carcinoma. BCC is a less urgent referral, ‘one or two months’. Must be an individual basis, however, and rapid growth would warrant more rapid referral as this is more likely an SCC or keratoacanthoma. Similarly, signs such as loss of lashes, ulceration, distortion of the tarsus and a linear scar might warrant faster referral.

When not referring, a photograph is essential and then a three-month review is sensible. The patient can also be instructed to return quicker if changes are noticed.

Treatment of benign lesions is no longer available under the NHS as a given, though biopsy is sometimes undertaken.