As always there was much of interest at this year’s conference, this year held in the space age Lakeside Center Building in Chicago. Much of the teaching focused on neurological concerns and there was much discussion around the TFOS DEWS2 report which this publication is also covering at present.

Current and ex-pat UK practitioners featured prominently. Professor Lyndon Jones of Waterloo University announced the rebranding of the internationally renowned CCLR research facility which is now to be renamed as Centre for Ocular Research & Education (CORE).

Speaking at the launch, Jones said: ‘We continue to partner with innovators in contact lens technologies on myriad programs, including materials formulation, care products, comfort initiatives, myopia control, dry eye, drug delivery and education. Yet we are also working with major and emerging pharmaceuticals companies, digital technology giants, and academic institutions around the world on complex and fascinating initiatives that hold incredible potential for vision correction and enhancement.’

In conjunction, CORE commissioned Los Angeles-based artist John Park to co-create a massive 12-feet by eight-feet acrylic mural during the meeting, depicting the complexity and potential of the eye and sight.

Other familiar faces included Professor John Flanagan who delivered the results of a trial of a novel ocular hypotensive therapy showing promise in animal models, and Dr Paul Chamberlain who presented his work on myopic progression limitation with a dual focus contact lens (see next feature for details).

As always, there were many concurrent strands of clinical education and you have to be most selective in deciding on what you can attend. Among the many excellent lectures was a presentation on lid lump removal which included audience interaction via remote control allowing them to influence a simulated procedure. Scleral lens fitting practice, low vision assessment and clinical decision making all featured highly. Here are some highlights from the clinical teaching sessions.

Neurology

There were seminars on papilloedema, and a fascinating session on brain disorders. ‘Optometrists are, or will soon be, the van- guard soldiers in the battle against diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis,’ began Dr Marina Bedny (Johns Hopkins University) at the start of a lecture on how blindness affects brain development. Using brain scans, she showed how the visual cortex in blind individuals is repurposed, and showed the differences between this structure in the blind and normal-sighted. Bedny’s team have been studying ‘higher cognitive takeover’ in the congenitally blind. These individuals are better at understanding the grammar of complex sentences and, on average, show superior memory.

Lakeside Center Building, Chicago

‘The brain is built to learn and adapt,’ Bedny continued. However, after early childhood, ‘it’s difficult to gain full perceptual function’ in adulthood. She cited a patient, blind since the age of three who, as an adult, had his vision restored following a corneal transplant, but never gained full perceptual abilities such as recognising gender and emotion in faces. This suggests that early visual experience is essential for development of the visual system. In the blind, their unique perception causes the visual cortex to stop acting as a visual centre, and instead become involved with higher cognitive functions.

Several sessions mentioned ONDRI (the Ontario Neurodegenerative Disease Research Initiative), a multicentre study looking at genomics, neuroimaging, and assessments of cognition as well as language, speech, gait, retinal imaging, and eye tracking in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and vascular cognitive impairment. ‘As an extension of the brain, the retina manifests morphological changes in neurodegenerative diseases,’ said Dr Chris Hudson (Waterloo). ‘Ultimately, spectral-domain OCT may play a role in diagnosis and monitoring,’ based on the results of ONDRI, which uses OCT to construct three-dimensional neurological images. As ONDRI gets ready to make its data public in the coming weeks, Hudson (himself diagnosed with Parkinson’s) reminded the audience that disease does not come in neatly defined packages.

‘One of the early visual symptoms in stage one is a loss of visuospatial working memory,’ Dr Vondolee Delgado-Nixon (Ohio) said. She reminded the audience of the game Simon, where a pattern is shown in a sequence and you have to remember the colours and the sequence. In practice, she suggested, you could show a patient an object in space and then remove it. In the early stages of Parkinson’s, they will often miss the mark on where that object was in the space offering a useful and simple indicator.

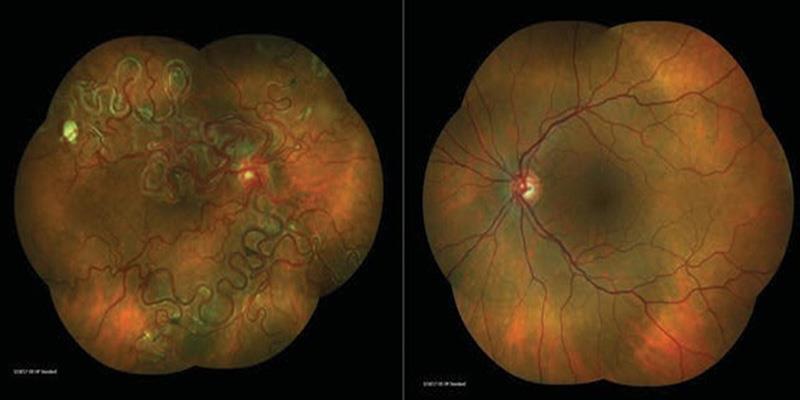

Finalist in photo competition showing vascular malformation in Wyburn-Mason syndrome

During a session called ‘The Eye as a Mirror of the Brain,’ Dr Robert Sergott (Wills Eye Hospital) offered six rules for OCT in his lecture, supported by clinical case examples. Each case helped solidify the concept that the retina, optic nerve and brain are all linked. ‘OCT gives you objective data as opposed to subjective data,’ he said. ‘We still get fooled as to what is an optic neuropathy and what’s a maculopathy, but OCT doesn’t.’

The six rules, according to Sergott, are:

1 Always image both eyes, optic nerves and maculas with OCT in suspected neuro disease.

2 Consider ‘Where is the disease?’ before ‘What is it?’

3 Decreased or increased thickness leads to the diagnosis.

4 White signal is ischaemia, lipid, haemorrhage, exudate or fibrosis. Black is oedema.

5 Always correlate fields with OCT, as 88% of a first associated field will contain artifacts.

6 Inner nuclear layer cysts occur in many diseases.

Glaucoma

With the excitement around TFOS DEWS2, I was interested in a study evaluating risk factors for developing ocular surface disease (OSD) in treated glaucoma or ocular hypertension patients. This found that OSD was related to the number of medications used, prolonged use of preserved medications and total benzalkonium chloride (BAK) exposure. Other research has found a link between BAK-containing eye drops and OSD. ‘Glaucoma patients treated with eye drops tolerate their first bottle,’ said researcher Dr Robert Fechtner (SUNY). ‘Two medications, three medications, they were up to 40% with substantial OSD signs and symptoms.’ He urged practitioners to think twice before adding more than one or two eye drops

Dr Lyne Racette (Indiana) offered a presentation called ‘Early Detection of Glaucoma Progression Using a Novel Individualised Approach’. Earlier detection methods, she argued, depend on realising ‘glaucoma does not progress in the same manner in all patients.’ In some, she said, ‘glaucoma is best detected using a structural test. In another person, perhaps, progression is detected first using a functional test. If we use the same methods for everybody, we may not be as sensitive as we’d like.’ Thus, in her research, ‘for each patient we used the first seven visits and ran 2,000 permutations of those seven visits on both structure and function’ using standard automated perimetry and frequency-doubling technology as the functional parameter and rim area and retinal nerve fibre layer thickness as a structural parameter. Using this data, her team developed a system to flag for progression with greater sensitivity.

Therapeutics

Dr Richard Marciniak (Colorado) underlined the significance of systemic drugs as a cause of eye disease. Topiramate, for example, is widely prescribed to help treat diseases ranging from epilepsy, migraine and psychiatric conditions to neuromuscular and neurologic conditions and obesity. Despite its widespread use, the medication can cause ciliochoroidal effusion syndrome, induced myopia and angle-closure glaucoma. ‘Whenever you see acute or subacute vision loss unexplained by objective ophthalmoscopic findings, you should consider drug toxicity,’ Marciniak concluded. ‘The patient may not realise they have accompanying systemic symptoms, so you need to ask for specifics.’

‘Before starting any treatment, practitioners must properly diagnose.’ This opened a session on collagen cross-linking therapy (CXL) from Dr William Tullo (New Jersey). Additionally, ‘now that we have CXL, we need to know if the cornea is, indeed, stable or if it’s progressing,’ according to Tullo. He considers it essential to establish a specific keratoconus diagnosis: abnormal posterior ectasia, abnormal corneal thickness distribution or clinical, non-inflammatory corneal thinning.

To confirm progression, Dr Andrew Morgenstern (Bethesda) emphasised that optometrists must note any two of the following:

1 Steepening of the anterior segment

2 Steepening of the posterior segment

3 Thinning or changes in the pachymetric rate of change.

These measurements can be achieved via a variety of tools on the market. Morgenstern warned of the dangers of skipping screening, specifically for children. ‘Myopia that we control is an axial length problem,’ he explained. ‘For a kid getting more and more myopic, you might just start controlling it, but you could be missing their actual disease if it’s keratoconus.’