Heredity or mutation

Normally we all possess 46 chromosomes made up of 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. Klinefelter syndrome is a chromosomal condition affecting boys and men. It is not inherited, but instead is due to an error during cell division called non-disjunction. This prevents the X-chromosome being distributed between the gametes, the egg and sperm cells. In essence, the egg cell that normally has an X-chromosome will have an extra X-chromosome or the sperm cell that normally has a Y chromosome may end up with another X-chromosome

(figure 1).

Therefore, if an egg with XX chromosome is fertilised by sperm with a Y chromosome, then we will get XXY child. Likewise, when a sperm with an X and Y chromosome fertilises an egg with a single X chromosome, the child will also have XXY chromosomes. In both cases, Klinefelter syndrome results. So Klinefelter’s is not due to gene mutation and inheritance but instead is due to their now being 47 chromosomes instead of 46.

Males with Klinefelter syndrome typically have small testes that produce reduced amount of testosterone. Shortage of testosterone affects sexual development and affected males usually display a number of characteristics, including:

- Infertility

- Delayed onset of puberty

- Breast enlargement

- Decreased muscle mass

- Decreased bone density

- Lack of facial and body hair

There are one in 650 males with Klinefelter. Nearly half of all males with the syndrome develop metabolic syndrome which may manifest as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, increased levels of abdominal fat and hyperlipidaemia.

There is also an increased risk of developing auto-immune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome. Individuals with Klinefelter syndrome have impaired social skills, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and emotional immaturity. Ten percent of Klinefelter syndrome patients are confirmed as having autism spectrum disorder.

Case

2012

A 16-year boy with learning difficulties came to the practice for an eye examination. He was highly myopic and his mother wanted him fitted with contact lenses. His general health was fine and he took no medication.

He was fitted with daily disposable contact lenses:

- R: 8.50 / -11.50DS

- L: 8.50 / -12.00DS

2017

Over the next five years, his myopia progressed until his refractive prescription was:

- R: -14.50DS (6/12)

- L: -17.50 / -1.75 x 20 (6/12)

He now decided against contact lenses and instead asked about laser surgery to correct his myopia.

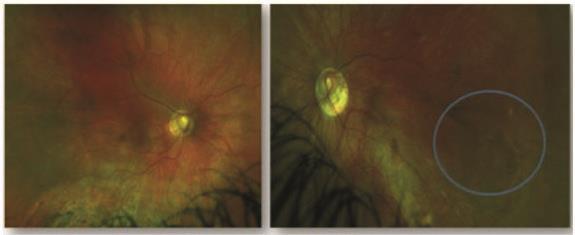

Fundus examination revealed a retinal hole on the left inferior temporal retina (figure 2) and he was referred to a specialist for retinopexy to seal the retinal operculated hole. Due to the continued progression of his myopia, it was inadvisable for him to undergo any refractive procedures at this stage and so, to keep his morale up, we discussed the possibility of an anterior lens implant once his myopia had settled.

Figure 2: Full colour scanning laser ophthalmoscopy images of the right and left retina of a high myope. Both eyes show some tilting, more noticeable in the left. The blue circle shows the presence of an operculated retinal hole in the left retina. Neither eye shows any sign of diabetic retinopathy

Figure 2: Full colour scanning laser ophthalmoscopy images of the right and left retina of a high myope. Both eyes show some tilting, more noticeable in the left. The blue circle shows the presence of an operculated retinal hole in the left retina. Neither eye shows any sign of diabetic retinopathy

2018

The patient was now diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes. During this medical assessment, the doctor noticed his small testes and diagnosed Klinefelter syndrome. As a result, the patient was prescribed metformin and testosterone. As previously (figure 2), he was R0/M0 indicating no diabetic retinopathy and his optic discs were tilted.

2019

The patient’s mother booked an urgent appointment as her son had developed a painful, photophobic and red right eye.

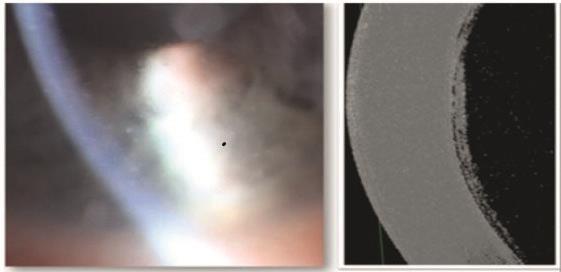

Slit-lamp examination revealed bilateral anterior uveitis showing marked anterior chamber cells and flare resulting in keratic precipitates (figure 3). The signs were more marked in the right eye. He was referred to an ophthalmologist for immediate

management of the anterior uveitis and was prescribed dexamethasone 0.1% steroid drops, qid for a month. It was thought that the uveitis was an autoimmune response associated with the Klinefelter profile.

Figure 3: Anterior chamber inflammatory signs due to anterior uveitis in a patient with Klinefelter syndrome. The slit-lamp image (left) shows fine keratic precipitation. A 3D anterior OCT scan (right) shows fine white dots in the anterior chamber space signifying the presence of inflammatory cells within the aqueous

Figure 3: Anterior chamber inflammatory signs due to anterior uveitis in a patient with Klinefelter syndrome. The slit-lamp image (left) shows fine keratic precipitation. A 3D anterior OCT scan (right) shows fine white dots in the anterior chamber space signifying the presence of inflammatory cells within the aqueous

Discussion

By their very definition, a syndrome affects a range of tissues and organs. Many chromosomal disorders are syndromic and so ECPs need to be aware of the likelihood of ocular involvement, whether indirectly through systemic diseases such as diabetes, or directly, as in this case where the patient developed anterior uveitis.

It is also important to remember the impact of such disorders upon cognitive and learning development as well as anatomy.

- Kirit Patel is an optometrist in independent practice in Radlett, Hertfordshire.