It is generally heartening to know that your young protégé is diligent in capturing abnormalities at a very early stage. In this article, I describe a patient who had been seen regularly by me for over 15 years but who, on his latest visit, saw our young optometrist who, on performing a slit-lamp examination, noticed a bulge in the iris and thought to inform me of the findings. The oncologist’s subsequent first line statement read, ‘His optician, Mr Patel, should be congratulated for finding this lesion which was asymptomatic and had never been noticed before.’ This is one of three cases of suspected uveal melanomas described in this article, while in the second article I will offer an insight into the monitoring of choroidal melanomas.

Case 1

A 65-year-old male patient was seen in our practice by a younger optometrist.

Clinical findings

• Unaided visual acuity; 6/7.5 R and L, and N5 with reading

correction

• Fundus examination; no abnormalities detected

• Anterior slit-lamp examination;

• Slightly narrowed angle on the temporal aspect of the right eye

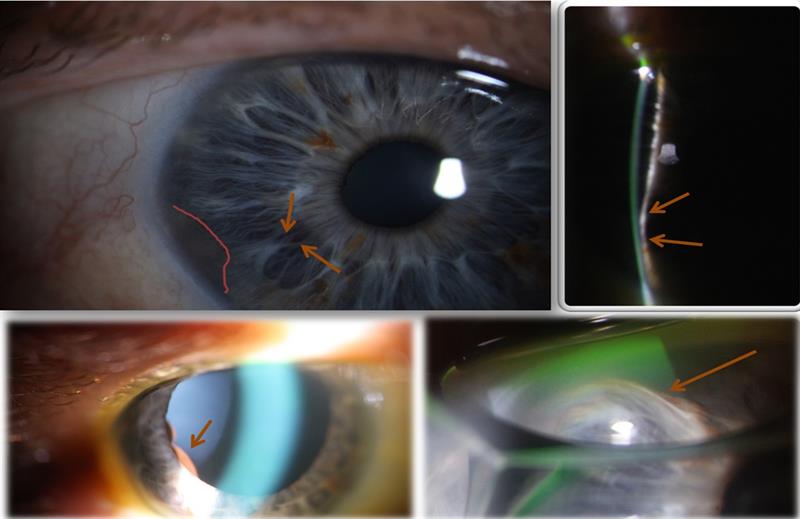

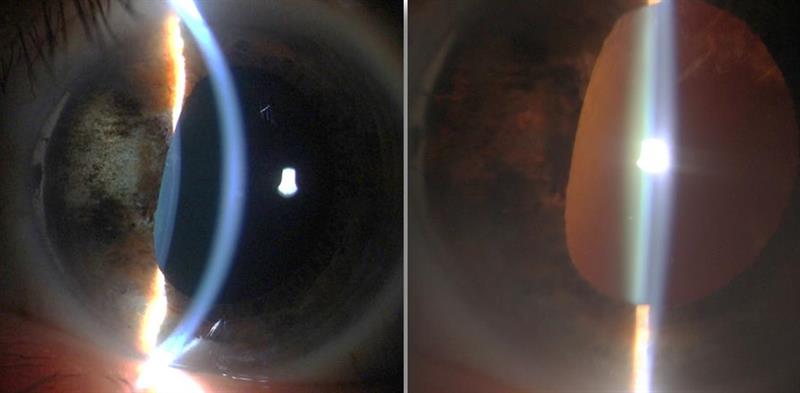

• At the edge of the right temporal iris was noted a pigmented area beneath the iris with no obvious vascularisation (figure 1)

• A bulge in the right iris adjacent to the pigmented area

• Post-dilation appearance; a double hump dark brown lesion

• Pupil margins showed no ectropion uveae

• Limbus showed no extrinsic vasculature

• Gonioscopy; a bulge obscuring the angle but no mass within the angle (figure 1)

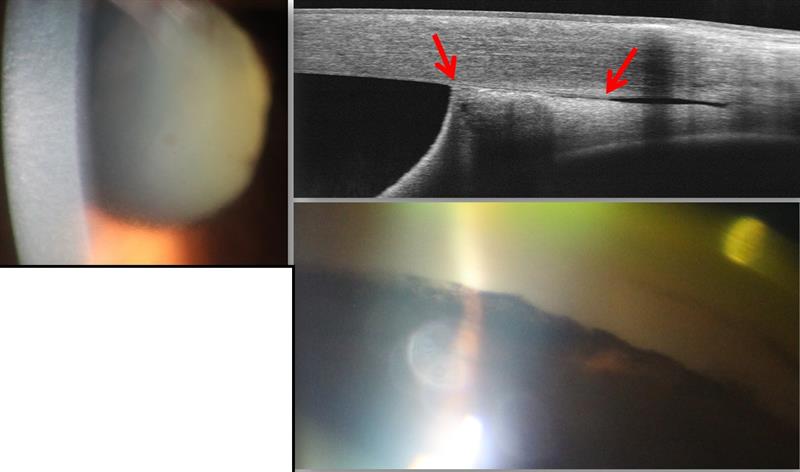

Figure 1: Top left; a pale, pigmented, apparently flat pigmented lesion (pink outline). Nasal to this, the arrows show where there appeared a slight bulge in the iris. Top right; a narrow beam reveals a clear bulging of the iris. Bottom left; dilation reveals a pigmented double hump likely located in the ciliary body behind the iris. Bottom right; gonioscopy revealed a larger mass, but no angle involvement.

Figure 1: Top left; a pale, pigmented, apparently flat pigmented lesion (pink outline). Nasal to this, the arrows show where there appeared a slight bulge in the iris. Top right; a narrow beam reveals a clear bulging of the iris. Bottom left; dilation reveals a pigmented double hump likely located in the ciliary body behind the iris. Bottom right; gonioscopy revealed a larger mass, but no angle involvement.

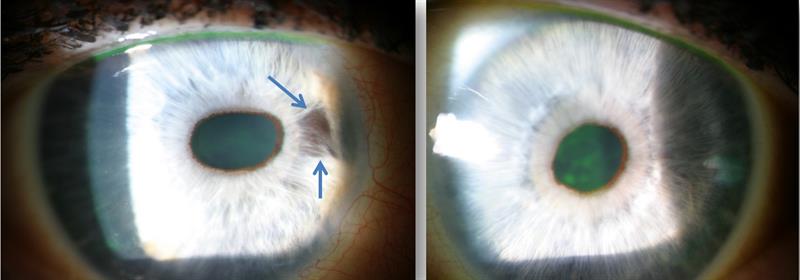

• Anterior OCT;

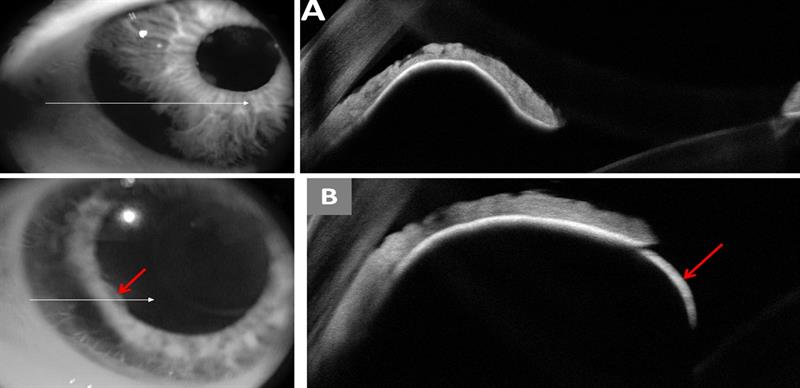

• A mass measuring 2.32mm in height, 4.03mm in length and 2.50mm in width (figure 2)

• Crystalline lens in the adjacent area appeared to be pushed downwards (figure 2a).

• The mass showed peripheral anterior synechiae, blocking the angle in that area (figure 2b)

Figure 2: (a) Anterior OCT showing the extent of the pigmented lesion (top left) and the ciliary body melanoma beneath the iris (top right), pushing down on the crystalline lens and raising the iris.

Figure 2: (a) Anterior OCT showing the extent of the pigmented lesion (top left) and the ciliary body melanoma beneath the iris (top right), pushing down on the crystalline lens and raising the iris.

(b) Anterior OCT image showing the ciliary body lesion at the edge of the iris (bottom left), and the rounded dome of the lesion (bottom right). The angle appears blocked in this area.

Management

The patient was referred via his general practitioner with a stipulation that he should be seen within two weeks at an ocular oncology clinic. He was seen by an eminent professor at Moorfields, and a diagnosis of early melanoma made, although a biopsy was not possible due to the lesion being so small. The patient was given the option of early plaque radiotherapy or close observation (every four months) to monitor growth of this small lesion. If there was documented growth, then they would undertake plaque brachytherapy. The patient opted for regular monitoring.

The detailed clinical report was as follows:

• Right iris showing a pale, slightly pigmented flat area temporally and, adjacent to that, a retro-iridial bulge in the inferior temporal iris

• There was no seeding (spreading) of cancer cells into the neighbouring trabecular meshwork

• There were no sentinel vessels (dilated episcleral vessels)

• Fully dilated examination showed a pigmented bulge visible just behind the iris

• Transpupillary transillumination showed a normal ciliary body shadow

• B-scan ultrasound revealed a temporal irido-ciliary lesion with a cystic iris element and a solid ciliary body component

• Both the pigmented lesions had an overall elevation of 2.6mm

The final diagnosis was recorded as: suspicious ciliary body irido-ciliary cystic/solid lesion, or a suspicious naevus and an early melanoma cannot be ruled out.

Case 2

A 59-year-old male was seen at the practice for his first consultation with no obvious complaints. He was a high myope and wore spectacles for distance which he lowered down his nose for reading. He had been smoking 15 cigarettes a day for the past 40 years, and took the following medication:

• Amlodipine for hypertension

• Atorvastatin for hypercholesterolemia

Clinical findings

• Refraction;

• R: -9.75 / -3.25 X 35 (6/12 N5)

• L: -10.25 / -2.25 155 (6/12 N5)

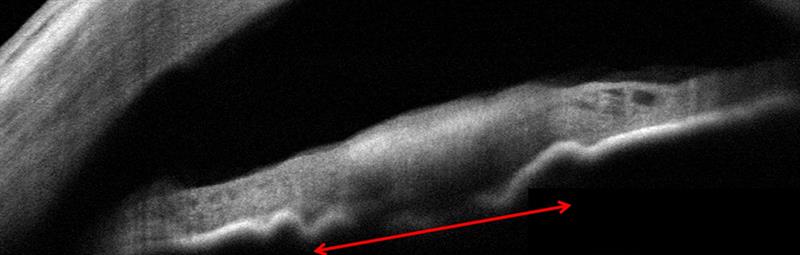

• Anterior slit-lamp examination; a pigmented iris naevus on the inferior aspect in the right eye (figure 3 top – no mention had been made of this by his previous optometrist)

Figure 3: Top; anterior OCT shows how the iris lesion has caused an undulation of the posterior iris pigment epithelium. There is no involvement of the angle. The lesion is measured at 1.8 x 1.0mm. Bottom; pigmented iris lesions seen inferiorly.

Figure 3: Top; anterior OCT shows how the iris lesion has caused an undulation of the posterior iris pigment epithelium. There is no involvement of the angle. The lesion is measured at 1.8 x 1.0mm. Bottom; pigmented iris lesions seen inferiorly.

• Anterior OCT (figure 3 bottom);

• A flat iris naevus, roughly 1.8mm in length and 1mm in height, with no obvious iris atrophy or iris root involvement

• No uveal ectropion

• No sectorial cataract

Management

The patient was informed about the iris lesion and told that this is likely to be a benign iris naevus. Since we were reporting it for the first time, and there had been no previous mention by any other optometrists, it was deemed sensible to refer the patient to an ocular oncologist for a second opinion.

The ocular oncologist undertook a battery of tests (including ultrasonography and gonioscopy) and concluded that this was indeed a benign iris naevus. The recommended action was for continued observation by the optometrist with digital photography and anterior OCT imaging. Ultrasound measurement of the iris naevus found it to be 1.8mm in diameter and 1.4mm in elevation. The patient asked the consultant about cataract extraction and was told that cataract surgery would be possible, but advisedly only if the iris naevus remained static for a period of five years.

Discussion

Melanoma, we should remember, is essentially a malignant lesion with uncontrolled cell growth, and new cells readily metastasise to other tissues separate from the initial lesion site. In normal metabolism, the gene P53 plays a key role in halting cell division if it detects damaged DNA. All malignancies, however, shut down P53 activity.

Uveal melanomas may occur in the iris (2%), ciliary body (18%) or choroid (80%). Uveal melanomas are the second most common form of melanoma, and the most common primary intraocular tumours in adults. They occur mainly in Caucasians. In children, retinoblastoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy. Uveal melanomas are, thankfully, rare with a global annual incidence of just 4.3 cases per million reported. In the UK, there are 2,500 cases of uveal melanomas compared to 32,000 cases of skin melanomas.

Iris melanomas, being the rarest form of uveal melanoma, can be small, asymptomatic and only noticed on routine examination. Their appearance varies from off-white to dark brown, and they can be difficult to differentiate from benign iris naevi. Iris melanomas have the best prognosis due to lowest rates of metastasis and therefore the lowest mortality. The five-year relative survival rate for people with iris melanoma is more than 95%. Signs of malignancy include:

• Large size

• Prominent iris ectropion

• Vascularisation

• Sectorial cataracts

• Secondary glaucoma (due to seeding of the peripheral angle structure)

Ciliary body melanomas pose a serious threat to life as they usually remain hidden behind the iris diaphragm and may grow undetected for longer periods of time before detection as compared to iris or choroidal melanomas. Local growth of the ciliary body melanoma can cause separation and disruption of the overlying ciliary epithelium leading to a reduction in aqueous humour production and consequently ocular hypotension. Growth into the crystalline lens may produce subluxation, lenticular astigmatism and cataract. The melanoma can grow trans-sclerally, through emissary vessels, and spread locally into the conjunctiva or orbit (figure 4).

Figure 4: A ciliary body melanoma (left image, 6mm by 3mm), treated by plaque brachytherapy. Note the localised tumour reduction and iris atrophy due to maximum dose delivery at the tumour site. Transillumination of the iris (right image) shows the full extent of iris depigmentation. The melanoma has cause pupil distortion but localisation of treatment has resulted in no cataract development.

Figure 4: A ciliary body melanoma (left image, 6mm by 3mm), treated by plaque brachytherapy. Note the localised tumour reduction and iris atrophy due to maximum dose delivery at the tumour site. Transillumination of the iris (right image) shows the full extent of iris depigmentation. The melanoma has cause pupil distortion but localisation of treatment has resulted in no cataract development.

An early indicator of an occult (hidden) ciliary body melanoma is a sentinel vessel. This represents one or more dilated episcleral blood vessels feeding the metabolically active tumour and is visible through the overlying conjunctiva. Unilateral low intraocular pressure (with inter-eye difference of 5mmHg or more) may be a further indicator of an occult ciliary body melanoma.

Iridociliary cysts are incidental findings and often mistaken for iris melanomas. If asymptomatic, they do not require treatment. Iris cysts arise from iris pigment epithelium, the most common located in the iris root. Ultrasound biomicroscopy is useful in distinguishing primary cysts of the iris pigment epithelium from solid uveal neoplasms.

Primary uveal melanomas arise from melanocytes in the uveal tract and most develop from a pre-existing melanocytic naevus. Pre-disposing factors include:

• Uveal naevus

• Congenital ocular melanocytosis

• Xeroderma pigmentosum

• Dysplastic naevus syndrome

• Family history of uveal melanoma.

Case 3

A 53-year-old female patient came in for her first eye examination, back in 2008, and reported no ocular symptoms. Observation with the naked eye immediately detected an abnormal right pupil.

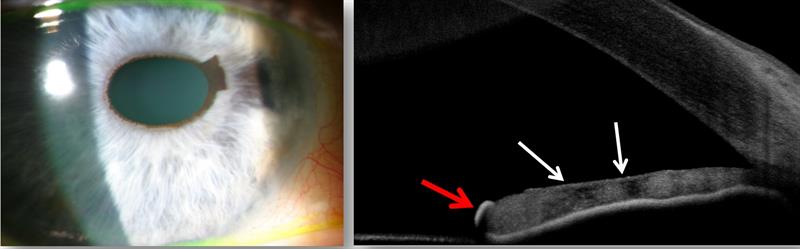

Clinical findings – 2008 (figure 5)

Figure 5: Right eye appearance in 2008. Right pupil appears oval and pulled nasally. The nasal iris appears to show a patch of atrophy (blue arrows). There is no obvious sign of sentinel vessels on the conjunctiva and there appears to be no corneal oedema. The left eye, by comparison (right image) shows a round pupil and no atrophy of the iris.

Figure 5: Right eye appearance in 2008. Right pupil appears oval and pulled nasally. The nasal iris appears to show a patch of atrophy (blue arrows). There is no obvious sign of sentinel vessels on the conjunctiva and there appears to be no corneal oedema. The left eye, by comparison (right image) shows a round pupil and no atrophy of the iris.

• Right pupil oval and pulled towards two o‘clock position (correctopia)

• Right iris atrophy on the nasal aspect

• Right angle wide and open

• Right cornea clear and healthy

• Intraocular pressures; R: 16mmHg, L: 14mmHg (@11.30).

Management

The patient was referred to an eye specialist for a second opinion and to ensure that no secondary glaucoma might develop.

Clinical Findings – 2011 (figure 6)

Figure 6: Right eye appearance in 2011. Feathery brown pigmented cap on the iris margin seen at two to three o’clock. There appears to be a slight further increase in nasal iris atrophy. Anterior OCT scan (right) shows naevus on the iris surface (red arrow), and the area of atrophy is seen as dark patches (white arrows). There are no peripheral anterior synechiae.

Figure 6: Right eye appearance in 2011. Feathery brown pigmented cap on the iris margin seen at two to three o’clock. There appears to be a slight further increase in nasal iris atrophy. Anterior OCT scan (right) shows naevus on the iris surface (red arrow), and the area of atrophy is seen as dark patches (white arrows). There are no peripheral anterior synechiae.

• Right iris;

• Atrophy same as 2008

• Feathery cap of pigmented naevus on the nasal anterior edge

• Intraocular pressures; R: 15mmHg L: 15mmHg (@12.00)

• Right anterior chamber; wide and open, no signs of peripheral anterior synechiae

• Pachymetry;

• Right central corneal thickness 573 microns

• Left 552 microns

Discussion

Iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome is a rare, unilateral genetic disorder most commonly seen in women between the ages of 30 and 50 years. The prevalence is 1 in 100,000 of the population and, in half of all cases, secondary glaucoma is present.

There are three features of ICE syndrome;

- Visible changes (distortion) of the iris

- Swelling of the cornea

- Development of secondary glaucoma

Signs associated with the condition include:

• Proliferative structural abnormalities of the corneal

endothelium

• Progressive obstruction of the irido-corneal angle by peripheral anterior synechiae

• Iris anomaly such as iris atrophy and hole formation

ICE Syndrome describes a disease state of which there are three recognised variations or sub-types:

• Chandler’s syndrome; the most common sub-type, representing around 50% of ICE syndrome cases. Chandler’s is characterised by corneal pathology and oedema and minimal, if any, iris change

• Essential/progressive iris atrophy; progressive and significant iris pathology resulting in iris atrophy is common

• Cogan Reese syndrome (or iris naevus); characterised by unique iris change where the anterior iris surface has pale brown pedunculated nodules or diffuse pigmented lesions. Iris atrophy is uncommon.

The ICE acronym comes from Iris naevus/Chandler’s/Essential.

All three share similar history and the same abnormal pathogenic mechanism of corneal endothelial pathogenic mechanism.

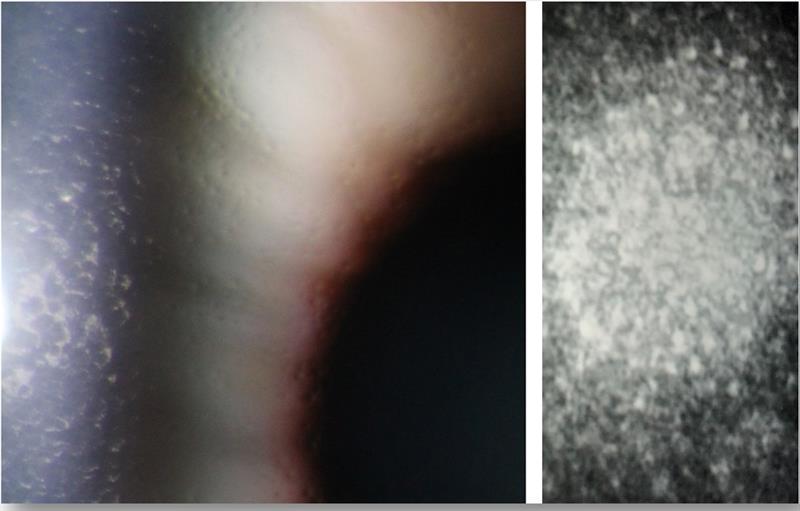

Polymerisation chain reaction (PCR) testing of corneal endothelial cells in ICE syndrome patients has found high percentage of Herpes simplex virus DNA in comparison to normal controls. It is therefore thought that viral infection with Herpes simplex virus or Epstein-Barr virus leads to low grade inflammation at the level of the corneal endothelium resulting in unusual epithelial-like activity by which normal endothelial cells are replaced by epithelial like cells with migratory characteristics (figure 7).

Figure 7: High magnification slit lamp view of the endothelium of a patient with Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (left image). Note the cell guttata and irregular appearance of the cells, together with corneal oedema seen best via retroillumination. The right image shows a confocal microscopy image of a patient with ICE syndrome. Note the regular size and shape of the healthy endothelial cells, while abnormal cells have hyper-reflective nuclei resembling the appearance of epithelial cells with microvilli.

Figure 7: High magnification slit lamp view of the endothelium of a patient with Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (left image). Note the cell guttata and irregular appearance of the cells, together with corneal oedema seen best via retroillumination. The right image shows a confocal microscopy image of a patient with ICE syndrome. Note the regular size and shape of the healthy endothelial cells, while abnormal cells have hyper-reflective nuclei resembling the appearance of epithelial cells with microvilli.

The altered endothelial cells migrate beyond the Schwalbe line onto the trabecular meshwork and at times onto the peripheral iris. Contraction of the tissue causes peripheral anterior synechiae and secondary glaucoma. Endothelial cell transformation also leads to corneal oedema and iris distortion, iris atrophy and eventually iris coloboma (hole).

The condition can be progressive and destructive. Remember, this is not a dystrophy and there are no losses of endothelial cells but, instead, proliferation of endothelial cells which migrate.

The occurrence of multiple nevi on the iris surface cannot be explained by endothelial cell proliferation. It has been suggested that mesenchymal cells that do not differentiate during the

seventh or eighth month of gestation remain on the corneal endothelium, the trabecular meshwork endothelium, and the anterior iris surface. A subsequent inflammatory process, such as triggered by a viral infection, then stimulates these cells to proliferate and to replace existing endothelial cells. This results in corneal oedema, iris distortion, iris atrophy and peripheral anterior synechiae. Also, the layers of mesenchymal cells on the surface of the iris may become melanocytes and develop into iris naevi.

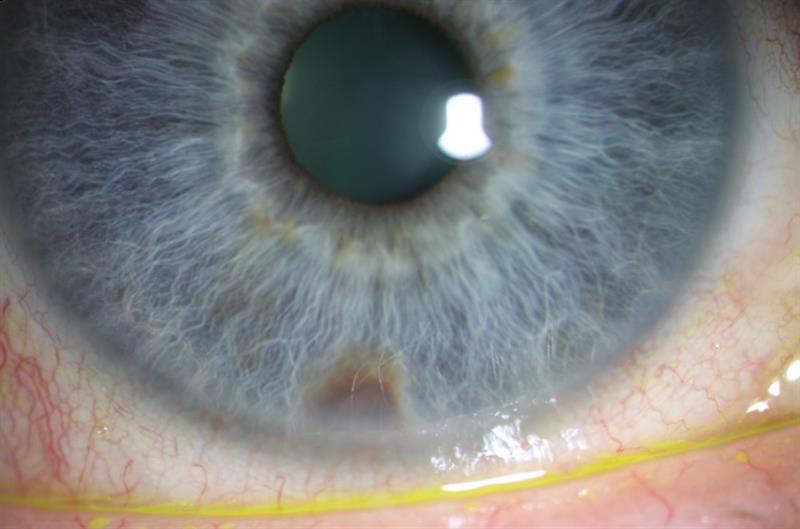

Secondary angle closure results from peripheral anterior synechiae obstructing the flow of fluid resulting in high intra ocular pressures and corneal oedema. The corneal oedema can also be a result of subnormal corneal endothelium pump function (figure 8).

Figure 8: Anterior OCT image (top right) showing adhesion of the anterior iris to the trabecular meshwork, described as peripheral anterior synaechiae. A gonioscopy view (bottom right) also shows peripheral anterior synaechiae likely to result in a significant rise in IOP due to blockage of the drainage angle. Pressures in such situations typically rise in excess of 50mmHg. The resultant corneal oedema and fixed mid-dilated pupil may be seen in the slit-lamp view (left image) and indicate a secondary open angle glaucoma is likely.

Figure 8: Anterior OCT image (top right) showing adhesion of the anterior iris to the trabecular meshwork, described as peripheral anterior synaechiae. A gonioscopy view (bottom right) also shows peripheral anterior synaechiae likely to result in a significant rise in IOP due to blockage of the drainage angle. Pressures in such situations typically rise in excess of 50mmHg. The resultant corneal oedema and fixed mid-dilated pupil may be seen in the slit-lamp view (left image) and indicate a secondary open angle glaucoma is likely.