Contact lenses can have an impact on the eye and ocular surface, although with modern lens designs in compliant wearers any lens-related changes are likely to be minimal and clinically insignificant.

In the third in a series of articles summarising the key findings of the BCLA CLEAR publications, a major review of the published evidence relating to all aspects of contact lens practice, Claire McDonnell highlighted the influence of the eyelids, adnexal glands and blinking on contact lens wear. Such factors are receiving greater attention from researchers, lens manufacturers and clinicians when considering contact lens design and materials.1, 2

Some of the ocular assessments outlined in the article may not always be performed routinely by clinicians, and more research is needed to understand correlations of the links to contact lens properties, ocular surface changes and on-eye contact lens performance. That said, techniques such as lid eversion are nowadays thought by most practitioners to be integral to a contact lens patient assessment. Indeed, this was the thinking behind one of the questions for discussion in this exercise.

You were asked to consider the details of the following case and then address the questions relating to it in your discussions.

Case scenario for discussion

A 32-year-old male patient has been wearing monthly replacement silicone hydrogel contact lenses for five years with a good deal of success. On previous annual aftercare appointments, you have found no concerns with his wear nor compliance with his care regime. He uses a multipurpose solution with containing polyhexanide as the preservative, and always includes a ‘rub and rinse’ step as advised. Other than occasional bouts of hay fever in the spring, for which he uses oral loratadine, he has no significant health concerns.

He attends for an aftercare today, some three months prior to his annual appointment, because in recent weeks he has found his lenses less comfortable. Each set of lenses becomes increasingly uncomfortable as the month proceeds and, throughout each day, the lenses seem to become increasingly ‘greasy’ upon blinking. The patient really wants to be able to continue full-time daily wear, but is increasingly intolerant of his lenses. Indeed, he attends today without lenses having last worn them yesterday for ‘around four to five hours max.’

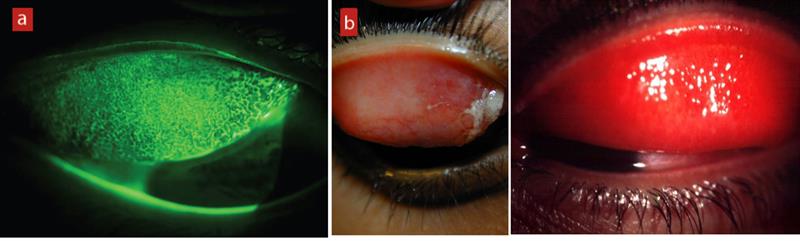

Figure 1 shows the appearance of the palpebral conjunctiva after lid eversion.

Questions to consider in your discussions:

- Do you always evert lids at an aftercare?

- What technique is being used to visualise the everted lid shown in figure 1?

- What would you record in your records to describe this appearance?

- What might be the cause of this appearance?

- What management options might you consider in the best interests of the patient?

Discussion

Most respondents correctly identified the appearance of contact lens-associated papillary conjunctivitis, or CLPC. This condition is known to result from a hypersensitivity response, but can also be a response to mechanical impact from lens wear, especially with contact lenses of a higher modulus. The history was vague enough to encourage both potential causes, but in most cases, the management considered most appropriate was to refit with daily replacement lenses.

Lid eversion

Using low magnification and a wider beam, lid eversion should be performed to assess the inferior and superior palpebral conjunctiva for hyperaemia and papillae. Fluorescein will pool around the boundary of papillae that might help their visualisation.3

Lid eversion is necessary to look for:

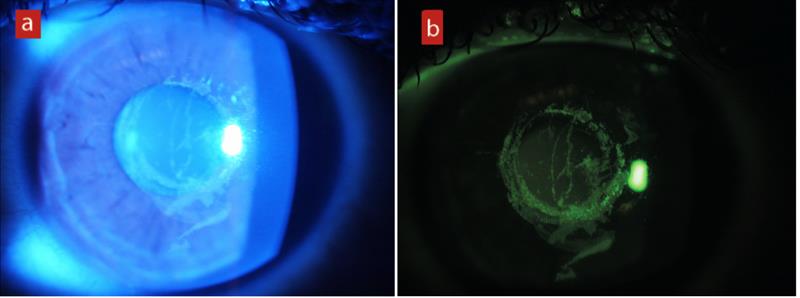

- Follicles (figure 2)

- Papillae (figure 3)

- Hyperaemia of the palpebral conjunctiva (figure 4)

Figure 2: Follicles seen in viral conjunctivitis

(Left to right) Figure 3: (a) Papillae in CLPC; (b) Papillae in vernal conjunctivitis in a non-contact lens wearer; 4) Hyperaemia of the palpebral conjunctiva

Most authorities suggest that lid eversion should be performed at all aftercare visits so that the palpebral conjunctiva can be assessed, and any allergic or mechanical effects of lens wear identified. The presence of follicles and/or papillae should be noted, along with their position, size and number.4

The majority of respondents confirmed that they would always evert the lid at the initial consultation but, for subsequent aftercare appointments, most said they would only evert if they felt it necessary.

For example: ‘I always evert lids at the initial consultation with any patient to establish a baseline of its appearance, to be able to compare at later intervals. I do not always perform that check unless probs occur that raises suspicions to look. I aim to evert lids once every couple of years.’

Another: ‘No, I do not always evert lids at every aftercare. If there is any discomfort or history of hay fever (as in this case), I would evert the lids. I also try to evert the lids for every patient we are seeing for the first time in our practice.’

And as one respondent reminded us: ‘Some patients actually decline lid eversion. So not every time.’

Technique

The everted lid was examined, as everyone realised, using blue light after the instillation of fluorescein and this was then viewed through an orange absorption filter to enhance the colour contrast of the image. By absorbing stray blue light, localised aggregation of fluorescein is more easily seen (figure 5).

Figure 5: (a) Corneal staining under blue light. (b) The same eye after introduction of an absorption filter

Recording

Most respondents recorded the appearance as either grade 2 or grade 3 contact lens papillary conjunctivitis. There were some useful points made here.

One respondent noted the papillary response to be present near the lid margin. ‘I would describe this as localised contact lens papillary conjunctivitis close to the lid margin. The variation in size of the papillae tends to indicate that this is caused by mechanical irritation from the higher modulus silicone hydrogel lens during blinking, which we do between 12 and 20 times per minute.’

Another reminded us that: ‘The image is with blue light, limits the description I can give compared to in practice as you cannot accurately grade hyperaemia.’

Other observations included: ‘There is mucin around the lid margin, there appears to be blocked ducts along the lid margin.’

Cause

A full review of the nature and causes of contact lens-associated papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC) is outlined in the BCLA CLEAR paper covering contact lens complications.5 CLPC is defined as an inflammatory condition of the upper tarsal conjunctiva and a disease unique to contact lens wearers. Both Type I (immediate reactions involving Immunoglobulin E) and Type IV hypersensitivity reaction (delayed reactions involving T lymphocytes) have been implicated in CLPC.

According to Stapleton et al: ‘However, the role of mechanical trauma caused by contact lens movement or the contact lens edge, which stimulates release of neutrophil chemotactic factors, triggering a local pro-inflammatory reaction is also plausible. CLPC is strongly associated with contact lens deposits, although the immunological trigger is unknown. High modulus SiHy contact lenses may contribute to the mechanical aspects of the disease due to increased mechanical or frictional irritation of the upper palpebral conjunctiva. Moreover, these contact lenses have increased propensity to lipid deposits, which may or may not be implicated.’5

In the localised form of CLPC, which is more common among SiHy contact lens wearers, papillae are confined to one or two areas of tarsal conjunctiva near the lid margin. In the generalised form, enlarged papillae are present across the entire palpebral conjunctiva. Local CLPC has been suggested to be initiated by mechanical stimuli, relating to contact lens edge design and thickness, that facilitate release of chemotactic factors attracting leucocytes. Similarly, generalised CLPC has been attributed to an immunological response towards contact lens deposits from denatured tear film proteins, which act as an anti-genic stimulus.

Dumbleton et al stated: ‘CLPC is typically attributed to an immunologic response to denatured protein deposits on the lens surface, but mechanical trauma may also be implicated in some cases. In silicone hydrogel lens wearers, the causative factors seem to be principally mechanical in nature and may be related to surface wettability changes or edge effects from these stiffer materials. It is also possible that an inverted lens could precipitate this response in some patients.’6

‘Silicone hydrogel wearers with CLPC may report several symptoms including a foreign body sensation or discomfort, itching, and stringy or ropy mucous discharge. In some cases, the presenting symptom may be fluctuating vision and lens mis-location, particularly during sleep. The associated symptoms of mechanically induced CLPC may be more rapid in onset than in immunologically mediated CLPC cases.’6 Several studies have shown how prolonged wear of higher modulus lenses, particularly the first generation of silicone hydrogel lenses, can lead to mechanically induced CLPC.7

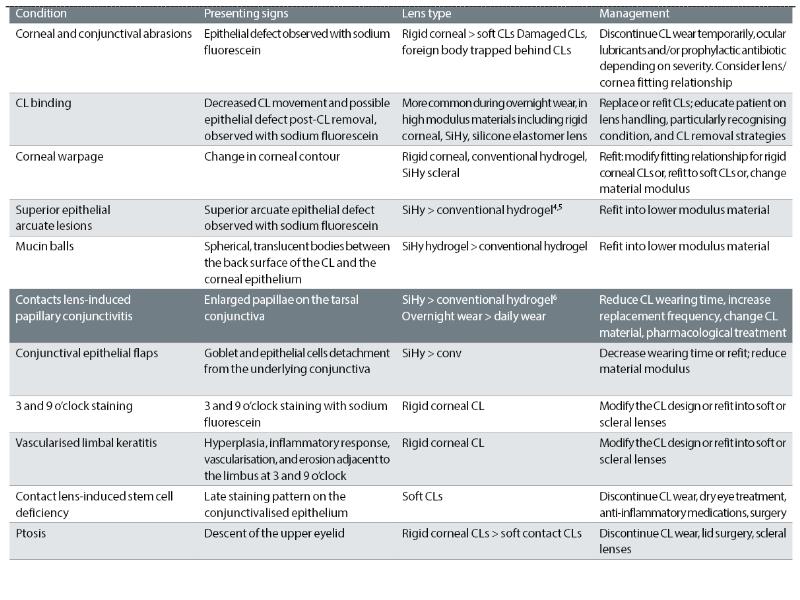

Table 1 (from the BCLA CLEAR paper on contact lens complications5) summarises all of the various adverse responses of the eye thought to result from mechanical insult from contact lens wear.

TABLE 1: Contact lens complications attributed to mechanical effects.5 CLPC is shown in bold type

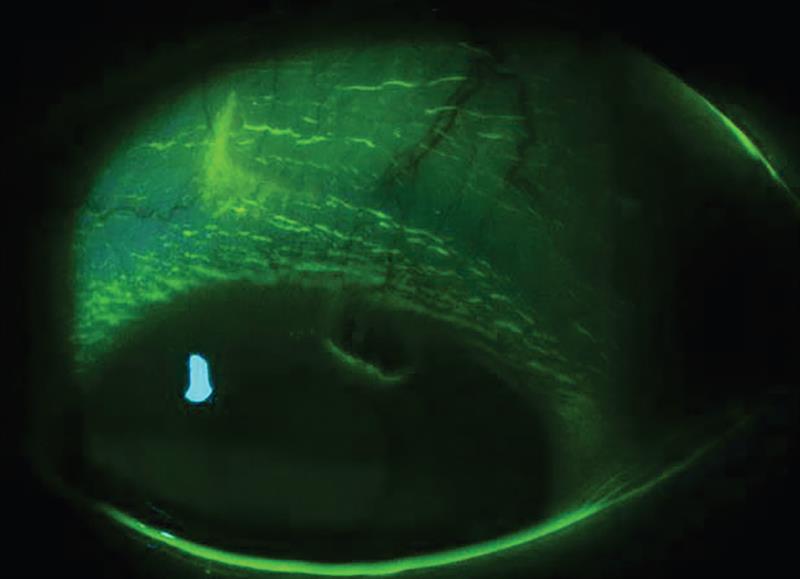

Another side effect of higher modulus lens wear, and one not mentioned in the details given for the case under discussion, is a superior epithelial arcuate lesion or SEAL (see figure 6). SEALs are an infrequent and often asymptomatic complication of conventional soft contact lens wear. The characteristic arcuate pattern of the full-thickness corneal epithelial lesion usually occurs in the area covered by the upper eyelid, within 2 to 3mm of the superior limbus in the 10 and 2-o’clock region.8

Figure 6: Superior epithelial arcuate lesion or SEAL3

In your responses, there was some debate about the underlying cause, most suggesting that there might be either an allergic response to deposits or solutions or a mechanical response to high modulus.

Management

Whether allergic or mechanical, the management preferred by all was to refit the patient with daily replacement lenses. This was after a period of ceasing to wear lenses and, in most cases, the introduction of anti-histamines to address the papillary response. For example: ‘I would generally refit the patient with a hydrogel daily disposable lens of low modulus with good wetting properties. I would also refer the patient to an IP optometrist colleague to prescribe some drops to reduce the inflammation.’

Neil Retallic comments

This case provides a nice reminder of the importance of inspecting under the eyelids in contact lens wearers. Identifying suboptimal performance early and a proactive approach to any responses can result in a good prognosis and avoid drop out.

Contact lens chemistry, edge design, surface properties, fitting characteristics, deposition and replacement frequency are variables likely to play a role in the development of CLPC. The first case was reported back in 1974, and prevalence levels range from 0.4% to 21.3%. The most common occurrence is linked with extended wear, less frequent lens replacement and high modulus soft SiHy materials.

A good history can support, with differential diagnosis to non-contact lens-related inflammatory origins and a comprehensive slit lamp assessment distinguishing papillae from follicles. Papillae are usually more discrete in appearance, with a redder central vascular core and, in the early stages, are typically around 0.3mm in diameter, which can progress to ‘giant’ status of over 1mm in size in those with CLPC. In comparison, follicles are often smoother, larger than typical papillae and a pinker colour with a white-yellow core, given they are accumulations of cellular level inflammatory agents.

To support patient management and ongoing monitoring of CLPC, separately grading papillae, hyperaemia and lid roughness is advantageous, as well as using the same grading system each time, given the differences between grading scales. Taking images further enhances record keeping and with patient communication.

Management typically includes optimising the lens fit, improving hygiene regimes, changing lens material and for soft lenses refitting with daily disposables to reduce risk, chance of deposition and exposure times. For some temporarily ceasing of lens wear may be required. For severe cases, pharmacological intervention with topical anti-inflammatory agents may be necessary.

- Neil Retallic is president of the BCLA.

References

- McDonnell C. BCLA CLEAR interactive 3 - Effect of contact lens materials and designs on the anatomy and physiology of the eye. OPTICIAN, 01.07.2022, pp 24-28

- Morgan PB et al. BCLA CLEAR - Effect of contact lens materials and designs on the anatomy and physiology of the eye. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 2021, 44, 192–219

- Hiscox R, Davidson A. Essential contact lens practice 4 – Slit lamp examination. OPTICIAN, 04.10.2019, pp24-32

- Hiscox R, Dhallu S. Essential contact lens practice 12 – The aftercare. OPTICIAN, 02.04.2021, pp18-24

- Stapleton F et al. CLEAR - Contact lens complications. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 2021, 44(2), pp330-67

- Dumbleton, K et al. Noninflammatory silicone hydrogel contact lens complications. Eye & Contact Lens: Science & Clinical Practice, 2003, Vol 29 (1), pp S186-S189

- Maldonado-Codina C et al. Short-term physiologic response in neophyte subjects fitted with hydrogel and silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Optometry & Vision Science, 2004, 81(12), pp911-21

- Holden, B et al. Superior epithelial arcuate lesions with soft contact lens wear. Optometry and Vision Science:, 2001, Vol 78 (1), pp 9-12