We are living in a time when there is an app for most things that you can think of; from monitoring how much water you are drinking each day to telling you where you parked your car in a pirate voice. With the increasing coverage of mobile phone networks and access to smartphones, the technology has evolved tremendously. Mobile phones are no longer simply a device to use for communication.

Mobile technology is increasingly being embraced in the medical community for a wide range of activities including real-time patient monitoring, telemedicine, health education, appointment reminders, and increasing adherence to prescribed medicine to name but a few.

There is an increasing use of technology in the delivery of eye care services. Technology is being used to improve eye care and increase the efficiency of services. At Peek we have evolved from developing and validating our initial product, a portable cost-effective kit to accurately check vision using a smartphone, to our current suite of tools that make eye health screening and surveys accessible to schools and communities.

However, in order to ensure that everyone has access to eye and healthcare services, we need to identify where people fall through the gaps in a system when trying to access services and how service providers can change that.

Challenges to eye care provision

As eye care professionals working in the UK, it is all too easy to assume that everyone who requires our service is able to access our help. When a patient presents at the GP with a headache, and is recommended to go see an optometrist, we believe that they will end up in our testing room because they were told to do so. When we refer a patient to the hospital eye service, we presume they will get to the hospital on the day of their appointment. We also believe that, when a patient is advised of a treatment, they will agree to it and comply with what is required for it to be effective. When we tell a patient to use hot compresses and clean their eye lids, we assume they will do exactly that.

But experience shows that such assumptions are often far from the truth. How many times have we taken a history and symptoms only to find that the patient is struggling to see because they are not using their spectacles as prescribed, or their eyes are dry because they did not go and purchase the dry eye drops that were recommended?

Over the past decade, I have been working in the field of public health optometry in low and middle income countries, with a specific interest in school eye health. At the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the focus of my PhD was improving the efficiency of school programs for uncorrected refractive error and I undertook two clinical trials for this, with a regional focus on India. I have learned from this period of study that a lot of the issues that are faced by eye health professionals in low and middle income countries are actually not so dissimilar to those we encounter in the UK.

In many of the countries that I work in, it is not easy to access spectacles, especially for children. They may be too expensive, too difficult to get hold of because the child lives in a remote or rural area, or they may just not be aesthetically appealing to children.

And while some of these issues may seem less of a challenge in the UK, I still often come across children here who are not wearing spectacles even though they were prescribed at their last visit. Upon speaking to the parents, it often transpires that they did not get the time to sort it out, forgot to come back to collect them or thought the spectacles were an unnecessary expense.

Ready-made spectacles

The first trial I conducted in India was to understand the number of children for whom ready-made spectacles would be suitable, so they could be dispensed on the spot and would not require parents to take time out of work to collect them from another location.1 Ready-made spectacles can offer a cost-effective solution for both the service provider and the parent/child.

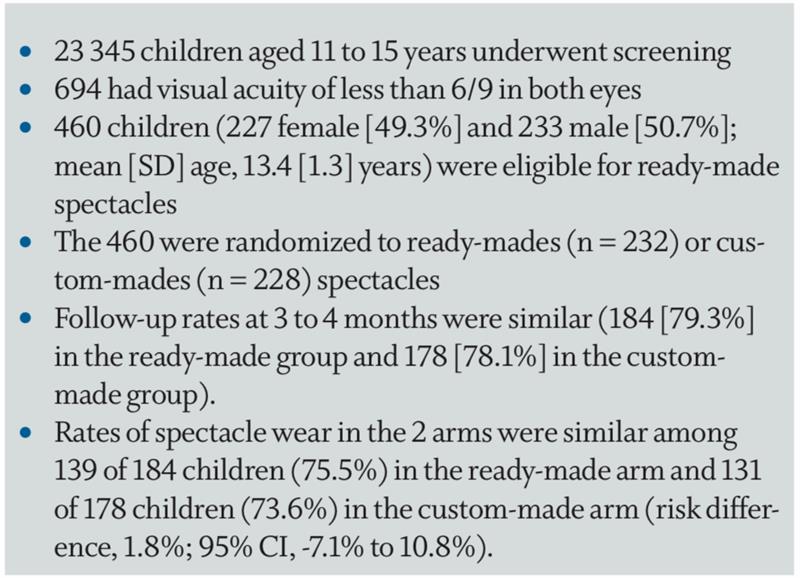

The trial had some interesting results in that we found 86% of children that required spectacles could be dispensed ready-made spectacles on the spot. Compared to the existing situation, where spectacles were often difficult to acquire, this is a staggering proportion of children who could be guaranteed to receive the treatment they need, spectacles, immediately on the spot. The results of the trial are summarised in table 1.

Table 1: Summary of results for ready-made spectacle trial1

Compliance

However, it is one thing to provide the treatment, but the impact that treatment has can only be measured if the patient adheres to it. There is evidence that children can be adversely affected by vision impairment and that it has an impact on their academic performance, visual functioning, behavioural development and quality of life. However, despite the benefits of wearing spectacles, there is evidence that a high proportion of children in many settings do not wear them. A recent review on this highlighted that this is a problem across all settings.2

Literature searches were conducted on Medline, Embase, Global Health and the Cochrane Library of publications from between January 2000 and November 2017 resulting in 777 references and subsequently 25 studies to review. These all looked at the compliance with prescribed spectacle wear for refractive error correction. The following was noted:

- The greater the refractive error, the higher the level of spectacle wear

- Socio-demographic reasons for non-compliance are complex as they are context specific

- Evidence that children become less compliant with spectacle wear with increasing age is not consistent

- Quantitative data indicate girls are more likely to be compliant with spectacles wear than boys, but qualitative studies highlight specific challenges faced by girls

The overall conclusion was that there was ‘considerable variation between studies in how spectacle compliance was defined, the time interval between dispensing the spectacles and assessment, and how compliance was assessed. There is need to standardise all aspects of the assessment of compliance. Further qualitative and quantitative studies are required in a range of settings to assess the biomedical and socio-demographic factors which affect spectacle wear compliance using standard

definitions.’2

Often, I have sat in my testing room and asked the child if they are wearing their spectacles and when they wear them, only to be met with a sheepish look that I know means they do not wear them as they should. To be honest, I was one of those children. I did not like how I looked in the spectacles and I was bullied for wearing them. The simple solution was not to wear them. But that meant living as an uncorrected high myope and walking around barely being able to see a few feet ahead of me.

Peek software trial in India

The second trial I conducted in India was using Peek software solutions to understand the whole system, from start to finish, and detailing:

- Initial identification of a vision problem for a child

- Referral

- Prescribing of spectacles

- Follow-up; do they go on to wear them?

Along this pathway, I used the software to trace the child and understand if and when they fall out of the system and why. I used various qualitative methods to analyse the effectiveness of health education and promotion for a range of interested parties, namely:

- Parents

- Children who wear spectacles

- Children who do not

- Teachers

With some of the work that Peek had previously undertaken in Kenya and Botswana, we had seen that setting up the Peek system to send automated text message reminders to parents to bring their children to their appointments had proved to be very successful. Indeed, when the Peek system was compared to conventional eye health programmes, the adherence to referrals was more than doubled.

In India, we used personalised voice messages for the

following:

- To parents to remind them to bring their child in for their appointment

- To explain to them why their child needs to wear their spectacles

- To demonstrate the impact that correction would have on their vision

We also created automatically-generated simulations of the child’s vision that would help parents and carers understand their child’s uncorrected vision in comparison to how it should look if corrected. These simulated images were made context-specific to reflect their environment, and included such scenarios as playing cricket in the street, viewing posters of Bollywood celebrities, and the view of a blackboard from the back of the classroom.

The Peek School Eye Health System also uses the Peek Acuity clinically validated vision check app to screen children for distance vision, and records that information so that it is visible to the eye health professional who sees them next in the process. An integral part of the programme is to engage with the school authorities, to ensure they support the initiative and also understand the importance of children being screened for any eye problems. At the end of the school visit, a list of the children in the school require any further checks or are dispensed spectacles is sent to the school via text.

Real-time data reporting is available on the Peek dashboard, to understand how well a programme is working and what aspects can be improved. From our recent work in Zimbabwe, we have learned that implementing gradual small changes to programmes can have a dramatic effect on the service delivery and people are more likely to get cheaper, faster, more equitable care.

The trial in India was ambitious, as we wanted to measure the impact and effectiveness of the programme. This is challenging even in a high resource setting as not all data is available or collected in a standardised way. In a typical low-resource setting, it is almost impossible; records are mostly paper-based and services often fragmented and under-resourced. Peek allowed us to make the patient journey visible and identify barriers at an individual and population level. Having this data available in a manner which is accessible to those that need to use it to make decisions is a game changer in all settings. In India, I was able to monitor in real-time the number of children being screened, reaching referral points, receiving their spectacles and then going on to wear them. This has not been done before in this manner and it highlighted very quickly where the gaps were and gave decision-makers the evidence they needed to make changes.

World vision

On October 9, 2019 (World Sight Day), the World Health Organisation published the The World Report on Vision.3 It is a report that is key to informing and persuading global leaders about the magnitude and unacceptability of unavoidable vision loss globally. The report advocates the need for ‘integrated people-centred eye care (IPEC)’. This approach to strengthening health systems should be the foundation for service delivery. ‘IPEC refers to eye care services that are managed and delivered to assure a continuum of promotive, preventive, treatment and rehabilitative interventions against the spectrum of eye conditions, coordinated across the different levels and sites of care within and beyond the health sector, and according to their needs throughout the life course.’ IPEC will also be a way to achieving universal health coverage.

Delivery of health care is very complex, and the notion of universal health coverage and how to measure it is multifaceted. There are three key data points that will helps us better understand whether people are receiving universal health coverage:

- Unmet need

- Met need

- Barriers to healthcare

These can be translated into measurable parameters of service, namely:

- Coverage

- Adherence

- Effectiveness

At Peek, based on our evidence from our work in Kenya, Botswana and India, we have refined our solutions and implemented them into programmes currently in operation in Zimbabwe and Pakistan. The results are showing how evidence-based practice can quickly translate into enabling eye health professionals to improve their programmes and increase access to eye care services. We have developed solutions to identify and address the barriers to better eye health service coverage. These solutions allow for task-shifting, so that specialist optical staff can focus on their individual tasks and more people can be screened over a given period of time.

By enabling eye health providers globally with a standardised way to measure their work and improve their services we can tackle the global vision crisis at the same time creating an impact.

Dr Priya Morjaria is a UK qualified optometrist, head of Global Programme Design, and Peek Vision Assistant Professor in International Eye Health

Further information on Peek Vision may be found at www.peekvision.org

References

- Morjaria P, Evans J, Murali K, Gilbert C. Spectacle Wear Among Children in a School-Based Program for Ready-Made vs Custom-Made Spectacles in India: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 Jun 1;135(6):527-533.

- Morjaria P, McCormick I, Gilbert C. Compliance and Predictors of Spectacle Wear in Schoolchildren and Reasons for Non-Wear: A Review of the Literature. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019 Dec;26(6):367-377

- World Health Organisation. World report on vision may be downloaded at; www.who.int/publications-detail/world-report-on-vi...