Thirty-six-year-old female patient Mrs AB attended the practice on two occasions in 2002 for an urgent appointment, having noticed a partial scotoma in her right inferior visual field. She had previously lost sight in her left eye due to a central retinal artery occlusion at the age of 23 with no obvious cause having been found. Since this episode, she was constantly anxious about her remaining vision.

She took no medication and her previous history included classic migraines. Following her left CRAO, she was investigated for hypercoagulability, which proved negative, although during her three successful pregnancies she was treated with clexane injections to prevent blood clots and thromboembolic episodes.

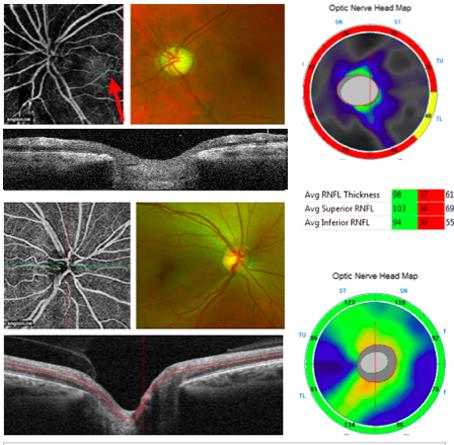

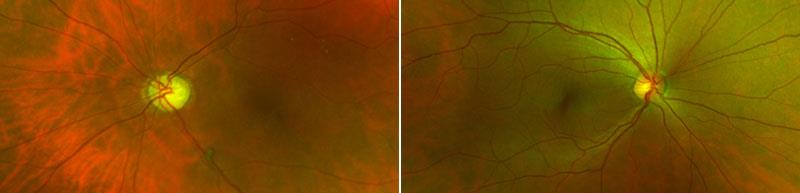

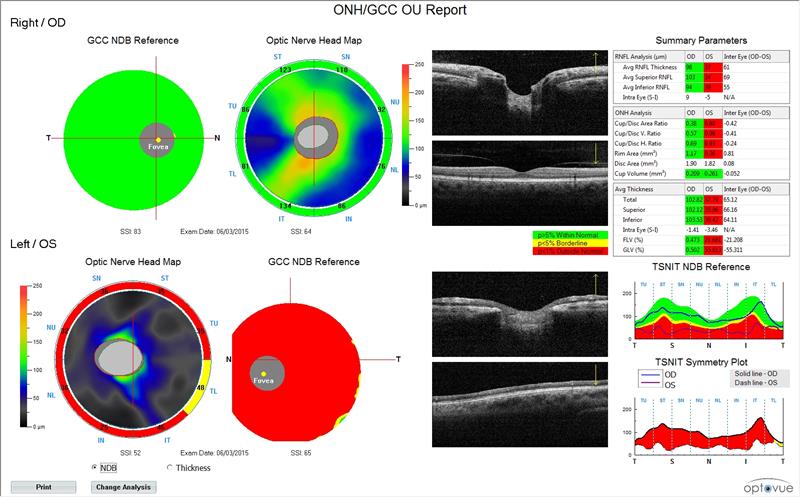

A thorough examination found she had unaided vision of 6/6 and N5 in the right eye and no light perception in the left eye. Fundus examination revealed no abnormality in the right eye while the left eye had an afferent pupillary defect and pallor of the left optic disc with attenuated vessels. Her intraocular pressures were R 16mmHg and L 14mmHg. Her visual field test revealed no scotoma in the right eye. Figures 3 to 7 show imaging data from the eyes.

She was referred to an eye specialist to throw some light on the visual disturbance. He arranged for full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, cholesterol, lipids and glucose levels to eliminate temporal arteritis, carotid artery patency and diabetes. Brain scans were also undertaken to rule out vascular abnormalities or intracranial neoplasms as well ruling out any abnormality of the optic chiasma or optic nerves.

All the tests were negative. A year later, she complained of frequent migraines, a recent episode involving stiffness in her left eye as well as bilateral scintillating scotomata. The ophthalmologist referred the patient to a neurologist to see if he could provide her with prophylactic migraine treatment.

The neurologist prescribed pizotifen as a prophylactic.

There followed frequent episodes of anxiety attacks as well as hyperventilation and no improvement in her migraines and visual auras. Seven years later (in 2010) she was seen by a cardiologist who diagnosed patent foramen ovale (a ‘hole in the heart’). This was a relief for the patient as there was a congenital reason for the premature central retinal artery occlusion in the left eye and maybe the frequent ophthalmic migraines.

After numerous appointments and cardiac tests, a decision was made to seal the atrial wall hole with a septal occluder which covered the hole with a disc on the right atrium side as well as disc on the left atrium. A catheter inserted through the vein in the groin and directed towards the heart was used to seal the hole in the heart wall. There was no guarantee that the ophthalmic migraines would be prevented but the cardiologist was hopeful, and more importantly this would reduce the risk of further occlusion or stroke.

How the heart works

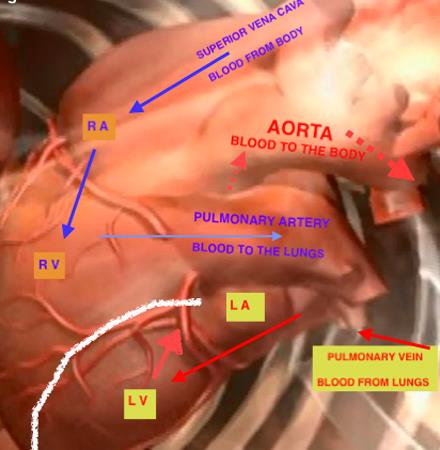

The heart circulates around 4.5 litres of blood throughout the body by contracting at 100,000 times a day. The superior and inferior vena cava (SVC and IVC) carry deoxygenated blood from the upper and lower parts of the body respectively to the right atrium (RA) and the right ventricle (RV) (figure 1). From the right ventricle, the pulmonary valve opens to allow deoxygenated blood to enter the pulmonary artery and into the lungs to pick up oxygen. The oxygen rich blood from the lungs then returns to the left atrium (LA) of the heart through the pulmonary veins. This blood enters the left ventricle (LV) which then pumps the blood out through the aortic valve into the main artery (the aorta) taking oxygen rich blood to the rest of the body (figure 2). Blood from the right atrium is separated from the left atrium by a septum. Valves allow blood to flow in one direction only and prevent blood leaking backwards.

Figure 1a: Heart illustration (courtesy of the Heart Society) showing the septum which prevents deoxygenated blood from the right atrium (RA) mixing with the oxygenated blood from the left atrium (LA). Figure 1b An echocardiogram depicting the flow of blood from the left atrium to the right atrium through the yellow glowing open septum (the patent foramen ovale)

Foramen ovale and migraines

In the foetus, the lungs do not function and the foetal heart has a structural opening between the left and the right atria called the patent foramen ovale (PFO). This opening allows the blood to bypass the lungs and flow directly to the left sided circulation, supplying blood to the brain and the body before returning to the placenta. The foramen ovale is kept open due to the right atrium being under higher pressure compared to the left atrium.

Figure 2: Flow of blood through the heart

At birth, the left atrium comes under pressure as blood arrives from the lungs resulting in closure of the foramen ovale. In 27% of patients after birth the foramen ovale does not close and remains fully or partially patent in adulthood. This hole is commonly known as ‘hole in the heart’. In most people the opening does not cause any complications but in some patients the opening can increase the chance of thrombus or blood clot (from deep vein thrombosis in the legs) to cross from the right atrium into the left atrium leading to a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Studies have found the risk of TIA and ischaemic stroke to be 50% in patients aged under 40 who have a patent foramen ovale, this dropping to 40% for the over 50s.

Figure 3: OCT-angiography (left eye top, right eye bottom) showing loss of fine capillaries around the left disc (black areas) with a tiny window of some capillaries in the lower temporal aspect (red arrow) which matches the optic nerve map (yellow sector TL)

It has also been found that about 23% of people with patent foramen ovale have a higher prevalence of migraine with aura, compared to 4% of the general population. The larger the hole the greater the risk of migraines with aura. One explanation might be that the passage of blood directly from right to left atrium allows unfiltered emboli, serotonin, nitric oxide and other migraine precipitating chemicals to reach the brain and induce migraine attacks. It has also been suggested that patients suffering migraine with aura have a higher frequency of underlying thrombophilic conditions which predisposes them to paradoxical emboli. The frequency of thromboembolic attacks appears to be reduced by administration of clopidogrel and aspirin. Finally, some researchers have suggested that 55% of migraine sufferers showed resolution of headaches and a further 25% had improvement following closure of the patent foramen ovale. NICE guidelines state that the safety and efficacy of PFO closure for the treatment of migraine is unknown and migraines should not be considered an indication for patent foramen ovale screening.

Figure 4: Left fundus image and right fundus image

Our patient had a history of a cryptogenic embolus that occluded her central retinal artery leading to a complete loss of vision in that eye at 23 years of age (figures 3 to 7). One can only conjecture that 20 years of anxiety at not knowing the cause of this sight loss could only have increased the risk of further problems.

Figure 5: Optic nerve head and ganglion cell complex data

Fear of further embolic events and loss of vision in the good eye along with the frequent migraines, hyperventilation attacks and numbness of extremities convinced the consultant of the value in undertaking the highly risky procedure of cardiac catheterisation for intra-atrial septal closure. It has been three years and our patient has not suffered a single further episode of migraine with aura.

Blood clots and anticoagulants

When tissue is injured the blood clots to stem bleeding and allow healing. Blood cells called platelets bind with the protein fibrin with activation of thrombin to form a blood clot (thrombus).

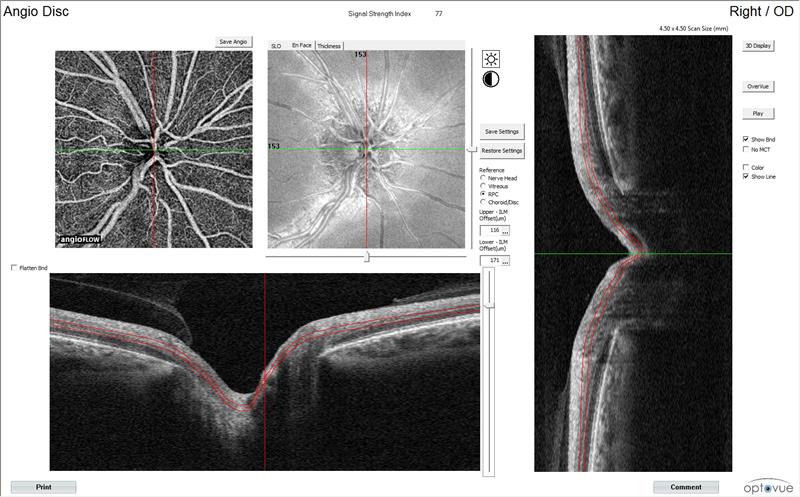

Figure 7: Right disc imaged with OCT-angiography

Sometimes, blood flow is sluggish enabling clotting factors to accumulate offering more opportunities for platelets to stick together and form a thrombus. The blood clot can detach and travel in the blood stream as an embolus, potentially by blocking blood flow to vital organs such as the heart, brain, eyes or lungs (pulmonary embolism). Immobility can also slow blood flow in the leg and pelvic veins (deep vein thrombosis).

Pregnancy, surgery, obesity and certain blood disorders can increase the risk of blood clots and anticoagulants may be required to prevent them. Warfarin is the most commonly used anticoagulant and is prescribed for certain medical conditions such as atherosclerosis or coronary heart disease. Low molecular weight heparin (clexane) is sometimes injected or given via a drip to inactivate thrombin and stop the formation of fibrin, the essential component of blood clots. Clexane is commonly used to treat deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, haemodialysis in kidney failure, myocardial infarction and to prevent clots following general or orthopaedic surgery.

Conclusion

I hope this article gives an insight into another important cause of migraines with aura and its eventual conclusion. Although one should bear in mind PFO, as a practitioner we should not alarm the poor patient unless definite evidence points to the contrary.

Kirit Patel works in private practice in Radlett, Hertfordshire.

Next year Kirit Patel begins a new series looking at rare and often life-threatening conditions presenting in optometry.