Scientists in Ireland think they may have found a way to assess brain health and nutrition through studying macular pigment in the eye, with implications for both the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). They have suggested a specific combination of nutrients and fish oil to enhance function and potentially slow the development of both conditions. The study still needs to be validated on a greater scale, but it could represent an exciting step forward in our understanding of the relationship between eye health and cognitive function.

The study

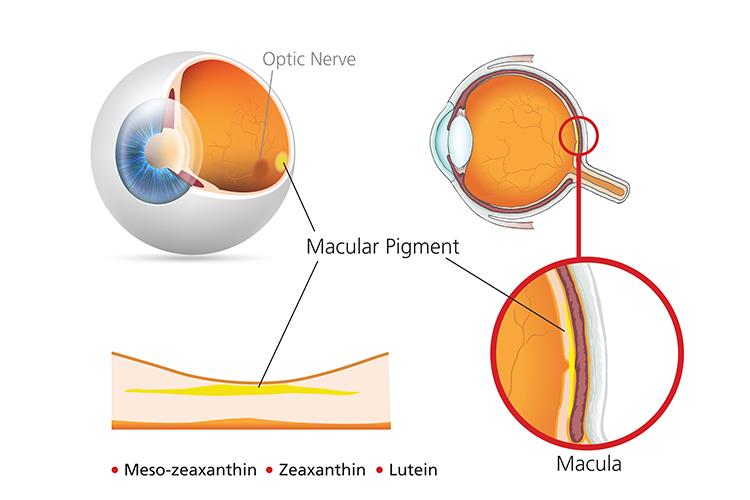

The research was led by Professor John Nolan of the Waterford Institute of Technology, who has spent the past 18 years studying the relationship between nutrition and eye health, and was conducted at the Nutritional Research Centre Ireland (NRCI). It investigated whether a combination of the macular carotenoids lutein, meso-zeaxanthin, zeaxanthin, along with Omega-3 fatty acids, would improve quality of life for patients with AD.

The researchers were already aware of the positive effect these carotenoids had on AMD – from a previous study by Prof Nolan – but were surprised to find a ‘significant relationship’ between macular pigment in the eye and a patient’s cognitive function.

‘When we did the study in Ireland with 5,000 participants, we measured their macular pigment,’ said Prof Nolan. ‘And when we measured their cognitive ability, we saw a striking relationship between nutritional, macular pigment in the eye and cognitive ability.

‘We know that the measures we do in the eye are a correlate for what’s going on in the brain in terms of these carotenoids. The eye is essentially a biomarker. It’s a window into brain nutrition and particularly by the measurement of macular pigment.’

Prof Nolan has shown that measuring macular pigment during eye tests enables an examination of brain health. The presence of very low levels of macular pigment is typically found in people with AD. When macular nutrition is enhanced, cognitive ability improves. Prof Nolan recommended taking the above combination of carotenoids and fish oil, which he said had positive effects on tissue concentrations of these nutrients.

Although the research needs to be scaled up, the findings are significant. Dr Alan Howard, founder and chair of the Howard Foundation that funded the study, called the work ‘one of the most important medical advancements of the century’. Currently, AD affects more than half a million people in the UK, with a cost to the NHS of £26bn a year. Wet AMD also costs the health service a substantial amount of money – £100m according to the National Institute for Health Research. The research was made even more timely as it coincided with Macular Health Week, which started earlier this week (June 25).

Teaming up with technology

The research would not have been possible had it not been for the advances in technology optics has witnessed. More sophisticated equipment, such as OCT, now enables greater accuracy in measurement and facilitates the identification of complex conditions, hitherto obscured by our relative inability to map certain parts of the eye clearly. One such piece of technology is Heidelberg Engineering’s Spectralis, which Prof Nolan has been using in his research since 2011.

The company has been collaborating with Prof Nolan and his team by providing a bespoke Spectralis OCT. A spokesperson for Heidelberg said: ‘Professor Nolan’s research utilises a customised Spectralis that uses dual wavelength auto-fluorescence to objectively measure macular pigment in the eye.’

‘We’ve used a bespoke module on the Spectralis that uses dual wavelength auto-florescence to excite the tissue at the back of the eye with different lights,’ Prof Nolan explained. ‘When you use different wavelengths of light, in this case blue and green, the system gives off different types of emission.

‘So essentially, you can digitally subtract the auto-florescence achieved with the blue light to that of the green light and you can map out the pigment profile. This is done very quickly and objectively,’ he said.

‘Professor Nolan’s work is very exciting and illustrates the potential of ophthalmic diagnostic imaging in a holistic approach to eye health,’ Heidelberg added.

The company is also hoping to make the module available to opticians in future. ‘We are hopeful that our collaboration with Professor Nolan will continue to yield the scientific evidence to make it possible for a macular nutrition module to become commercially available on the Spectralis platform in the future,’ said the spokesperson from Heidelberg.

A changing role for optometrists?

Optometrists already embrace the clinical dimension of their profession but there is a growing recognition of the need to do more, in part to ease the pressure on hospital services. This change in perspective was borne from a desire in the optical community to deliver the highest standards of care, and has been facilitated by new technology that enables more rigorous assessment.

For example, one Edinburgh based optometrist who Optician spoke to recently discovered an optical abnormality in a patient with a form of cognitive impairment. This was obtained through an extensive assessment using an OCT. After referring the patient to the nearby hospital, it transpired that they were living with a tumour close to their brain that was causing them enormous distress. While this may be an uncommon story, it serves to illustrate the expanding role that optical professionals are playing in the delivery of clinical care.

Prof Nolan (pictured) saw this clinical angle extend beyond that of referrals and the identification of potential conditions. ‘Optometrists should be looking at opportunities to objectively measure macular pigment,’ he said. ‘When they do that they can see whether the amount of this pigment is very high or very low. What our data shows is that typically in patients with Alzheimer’s, it’s very low.’

He would also like to see optometrists playing a greater clinical role in helping people understand the nutritional capacity in the brain and the concomitant effects on eye health. ‘The optometrist community is already very proactive in this space. They probably use nutritional supplementation more than the medical doctors at the moment in the UK,’ he added.

‘I certainly would suggest recommending nutrient supplements to patients. But I think the key thing is that they need to recommend supplements that have appropriate scientific testing in terms of stability and efficacy. There are a lot of different supplements out there,’ said Prof Nolan.

Much has been made recently of the health benefits of having a Mediterranean diet, but Prof Nolan asks, ‘what does that actually mean?’ He lamented the blanket recommendation of such diets given there is little probing into the specific parts of the diet that bring about benefits to health. ‘There are a lot of components to that diet, so full compliance to it is extremely difficult,’ he said. ‘Scale that up to an aged patient and they’re certainly not going to achieve a Mediterranean diet in appropriate substance.

‘The question then becomes: what part of the Mediterranean diet is most valuable for the retina and brain? Now we know that they both contain so much of these particular carotenoids and the brain also has these omega 3 fatty acids,’ he said. ‘It makes absolute biological sense to me to find a way to enrich those nutrients in the older population and those that do not get enough nutrition.’

Based on his previous work on visual performance, for which he is best known, he suggested the use of lutein, meso-zeaxanthin, zeaxanthin is best as a supplement for improving visual function. ‘I think it’s now accepted that for general eye health and visual performance these three carotenoids are key, not just because of their anti-oxidant properties but because of their optical, and specifically their blue light, filtration properties.’

He continued: ‘That’s really been what we’ve tested for 15 years. When you scale that up to AMD we know macular pigment is the risk factor for the condition. We know when we optimise this pigment in patients with early AMD, that we enhance their visual performance.’

It may also offer the potential for a reversal of information exchange. People with AD are often overlooked when it comes to eye care, perhaps because of its perceived triviality compared to their existing condition. But optometrists should now recognise that the two might be linked through a reference point of macular pigment. Encouraging people with AD to get an assessment of their eye, potentially finding other macular deficient conditions, could have a remarkably beneficial impact on their standard of living and quality of life.

Conclusion

Given the potential impact of such a discovery, if validated, optometrists may well find themselves in a position to expand the remit of their clinical care. A focus on macular pigment during eye examinations could enable a more holistic appraisal of brain health. Besides from the obvious benefits to patients, this could also increase the optometrists’ understanding of the relationship between eye health and the brain.

Prof Nolan currently thinks the relationship between eye health, nutrition and cognitive ability is under-appreciated. He argues that if it is recognised by optical professionals to the degree it should be, it would lead to greater understanding of all three and the role nutrition plays in sustaining both the eyes and the brain. ‘We can now use the eye as a window into the brain with respects to understanding its nutritional markers and that’s a hugely valuable asset to have, both in terms of research and clinical practice,’ he said.

Whether the research will revolutionise our understanding of AMD or AD will depend on further trials, but it is a positive step toward a greater understanding of the relationship between eye health, nutrition and cognitive ability.