It has now been nearly three years since the first blue light filtering lens products appeared on the market. While comfort and glare reduction made up part of the story, the headline for their introduction was the filtering of a band of light in the blue spectrum above 380mm.

Among those seeking to educate the public was Essilor with its Seeing Blue initiative, which formed part of the Think About Your Eyes awareness campaign. Earlier research, it said, from the Paris Vision Institute that suggested ‘bad blue light’ could damage cells within the eye. Essilor engaged 400 practices in an awareness campaign.

Professor John Marshall, who lectured to a packed audience at Optrafair earlier in 2014, sensationally featured in the Daily Mail. It said the eminent ophthalmologist had stockpiled incandescent light bulbs in preference over compact fluorescent lamps and linked the move to the same blue light wavelengths. Despite Prof Marshall’s comments playing down fears, the story was too good for the Daily Mail to resist and it ran a piece with dire warnings that the bulbs could lead to blindness and skin cancer.

Prof Marshall said at the time: ‘Low energy light sources have blue and UV components that do not in any way help in vision. They are redundant in vision and the shorter higher-energy wavelengths give rise to photochemical damage. These are not going to cause AMD and cataract but they are certainly potential risk factors. If you don’t need it why expose people to the risk of it?’

The watershed moment for optics came with the censure of Boots Opticians by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), which upheld a complaint about claims being made and the protection blue lenses might offer.

An advertisement in the national press in January 2015 had claimed that many modern gadgets, such as LED TVs and smartphones, as well as energy-saving light bulbs, emitted a certain type of blue light that could cause a person’s retinal cells to deteriorate over time. The multiple went on to say its Boots Protect Plus Blue lenses could filter harmful blue light and ease eye strain and fatigue.

In its assessments, the ASA said that while the advert acknowledged other factors that could affect people’s eyes, it considered that consumers would interpret it to mean that by filtering out harmful blue light in particular, they could reduce the deterioration of their vision later in life.

Boots had provided evidence for its claims but, said the ASA, it had been suggested that sunlight and not blue-violet light in particular, might be a risk factor for the early onset of AMD. The ASA went on to say the multiple did not provide evidence that the reduction in the amount of harmful blue light entering the eye would lead to a significant reduction in the amount of retinal damage caused.

The ruling dampened lens manufacturers’ keenness to promote the health benefits of blue lenses but elsewhere the idea continues to be pushed out to the public. This month’s Men’s Health carries a reader’s letter on eye strain in the office with an answer, from a New York university doctor, including the line: ‘One issue you may wish to be aware of is the gradual, insidious damage done by blue light coming from screens.’

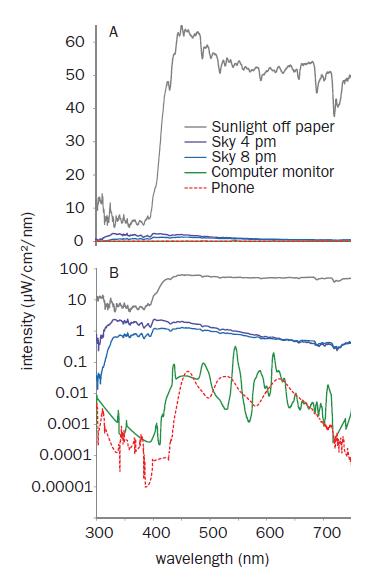

Figure 1: Comparison of the intensity of various sources of blue light

Misinformation surrounding the danger posed by the blue light emitted from digital devices abounds. This has prompted Bath community optometrist Mike Killpartrick to ask vision scientist, Dr Shelby Temple, senior research associate at the University of Bristol, to put the record straight.

He put together a document saying messages about the dangers of blue light from phones, tablets and computers were misleading and only consider wavelength not intensity.

He said: ‘We have followed the publicity given to the development and claimed benefits of various “blue light filtering” lenses with interest.

‘However, there appears to be a certain amount of confusion as a result, including the implication that blue light emitted by devices such as smart phones, tablets and computer monitors may contribute to the “blue light hazard” and resultant phototoxicity thought to be a possible contributory factor in the age-related processes associated with macular degeneration.

‘It is important to understand that although these devices do generate blue light in the 380-450nm range, the radiant energy is extremely low.

‘Measuring at 450nm the absolute irradiance of a phone with a white screen at its brightest setting produced an intensity of only 0.05µW/cm2/nm, whereas the blue sky at 90º to the sun at 4pm produced an intensity 400 times greater at 20µW/cm2/nm, and sunlight reflecting off of white paper produced an intensity at 450nm, a thousand times greater than the phone at 60µW/cm2/nm (see figure 1).’

Dr Temple said this meant to be exposed to the same amount of dangerous high energy photons during a 20 minute walk or drive to work, you would need to spend 133 hours looking at your phone or computer screen continuously. A one minute look at a white sand beach or snow on a sunny day, he said, would be the same as over 16 hours of looking at a phone. It should also be borne in mind that cellular repair mechanisms are likely to be more effective over long term exposure but less effective in short term bursts of high radiant energy though, he added.

‘This does not fully capture the true impact of the difference since these measurements were made at 450nm, which is close to the peak absorbance of macular pigments, but at 400-420nm a phone or LCD monitor produces almost no light, while the blue sky and reflected sunlight are just as intense as they are at 450nm, making the difference closer to 400,000-1,000,000.

‘These measurements should not be confused with the possibility of short wavelength light effects upon circadian rhythms or night driving performance, which are completely unrelated topics.

‘In summary, it would seem highly improbable that phones, tablets, monitors and other similar devices pose any significant risk in terms of age-related macular degeneration,’ Dr Temple said.

‘UV protection for all’

Paul Morris, director of optometry advancement at Specsavers

‘At Specsavers our advice, products and services are tailored to the needs of the customer in an evidence-based way. The current evidence suggests that the harmful blue light emitted by devices, lower energy bulbs, etc, is significantly below that emitted by normal sunlight and therefore the benefit to the patient of a bespoke product is limited. However, we are committed to educating the public on eye protection and UV protection for all, especially children, which remains a strong focus for us in individual consultations and as a wider message. All our children’s glasses contain free single-vision lenses with a UV filter.’

‘Order of magnitude’

Peter Black, immediate past president and an advisor to the Association of British Dispensing Opticians Board

‘While it may be that digital devices in the past emitted high levels of blue light, the evidence from Public Health England is that no digital device (smart phone, laptop, tablet computer) currently on sale, and indeed no currently available LED light bulb, emits a level of blue light even close, by an order of magnitude, to the exposure possible from a blue sky on a clear day, against which the devices were compared. It should be noted that the greatest exposure to blue light is from exposure to white light of which blue light forms a part, and as such direct exposure to the sun, or extended exposure to ophthalmic examination of the eye are the greatest risks.

‘That said there appears little doubt that blue light may be harmful, and since it is more easily scattered, it is beneficial to reduce its impact. As dispensing opticians we have long appreciated the benefits of attenuating blue light – traditionally using brown, yellow or amber filters of varying transmission profiles. Blue light attenuating ‘clear’ lenses – whether coated or within the mix of the lens material – are simply another weapon in our armoury and the feedback from patients is that most of them find the lenses more comfortable both when using screens and when driving at night, though some comment they prefer the more neutral reflex of traditional broadband AR coats. I think the jury is still out on the impact of blue light on circadian rhythm and sleep patterns and we should steer clear of making such claims until the evidence base exists.’