A study published in January this year has demonstrated the links between pandemic-related home confinement and rates of myopia in children. Conducted in Feicheng, China via optical school screening programmes, the study made use of 194,904 test results collected over six consecutive years.

The study found that confinement at home due to the pandemic appeared to be associated with a substantial myopic shift in children. In children aged between six and eight the prevalence of myopia increased by up to three times in 2020 compared to results from the previous five years. Compared to screening results from 2015-19, these children were, on average, -0.3 dioptres more myopic.

The growing prevalence of myopia in children has been the subject of a warning from the World Health Organization, which estimated that half of the world’s population would be myopic by 2050.

In previous studies too much time spent indoors, or not enough time outdoors, had been linked to both more severe cases of myopia in children and more prevalence of the condition. In the Feicheng study, researchers were able to test this theory on a large scale when the Chinese government enacted a nationwide school closure in January 2020. The study’s authors explained: ‘It is estimated that more than 220 million school-aged children and adolescents were confined to their homes.

‘Although these efforts have been shown to control the pandemic in China, concerns have been raised about whether the period of lockdown may have worsened the burden of myopia due to significantly decreased time spent outdoors and increased screen time at home.’

Scale of study

As Chinese schools were closed and children’s lessons moved online, the study’s authors were presented with an opportunity to investigate these concerns. All children in Shadong, Feicheng, aged between six and 13 had been screened for eye health

issues in September every year since 2015.

On the 2020 screening date, after schools had reopened, children wearing contact lenses were asked not to wear them while those using ortho-k were asked not to wear the lenses the night before the screen date. Children wearing spectacles were also asked to remove them for the refraction test.

Over 120,000 children were examined using a Spot Vision Screener, which flagged students for a complete eye exam if it discovered significant refractive error, anisometropia or strabismus. For the sake of the study, myopia was defined as a spherical equivalent refraction (SER) of -0.50 dioptres or less.

Results

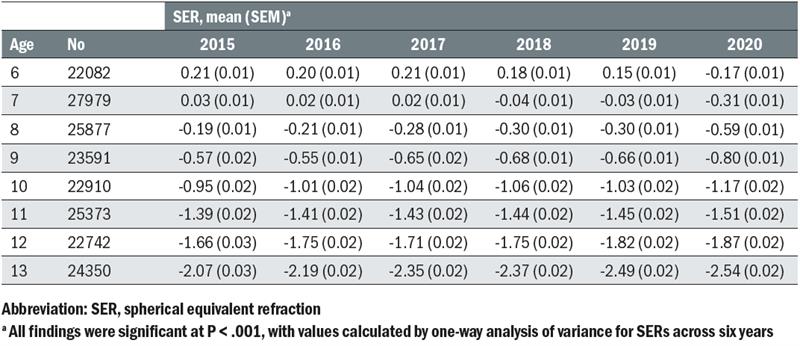

Researchers found that mean SER in children was relatively stable for all age groups in screenings conducted from 2015 to 2019. SER was significantly decreased in 2020 compared to previous years however, especially in children aged six, seven and eight.

The largest decrease in SER was found in the youngest children the study covered. The 2020 results showed that six-year-olds’ mean SER decreased by -0.32D from 0.15 in 2019 to -0.17 in 2020. Mean SER decreases were almost as large for the children aged seven and eight, with figures falling by -0.28 and -0.29 respectively.

Table 1: SER values during each year in school-aged children

Table 1: SER values during each year in school-aged children

Myopia was not just more severe in the children that formed part of the study, it was also more prevalent. Between 2015 and 2019, the highest prevalence rates for myopia were 5.7% of children aged six in 2019, 16.2% of children aged seven in 2018, and 27.7% of children aged eight in 2018.

In 2020, myopia was significantly more prevalent than these former highs. A total of 21.5% of children aged six were myopic according to the 2020 results, alongside 26.2% of seven-year-olds and 37.2% of eight-year-olds.

Nine-year-olds in 2020 also saw the highest prevalence for myopia across the six years of measurement, although the figure was not substantially different from the second highest prevalence for this age group in 2018. However, the prevalence of myopia in 2020 ceased to be the highest among children between the ages of 10 and 13.

In the discussion segment the study’s authors explained: ‘To our knowledge, we provide the first evidence that the concern [around lessened outdoor activity being significantly associated with a higher incidence of myopia] may be justified, especially for younger children aged six to eight years.’

They added: ‘If home confinement is necessary, parents should control the children’s screen time as much as possible and increase their outdoor activity while maintaining safe social distancing.’

The data also showed that mean SER in children was relatively stable across all age groups despite the higher rates for those aged between six and eight. The study’s authors explained that while there were statistically significant myopic shifts in children aged between nine and 13 the large sample size led them to not consider these shifts as clinically significant.

This was despite older children in the studied population completing more intense daily learning over 2.5 hours compared to those aged between six and eight, who completed just one hour of online learning. ‘These findings led us to the hypothesis that younger children are more sensitive to the environmental change than older children,’ explained the researchers. ‘Younger children’s refractive status may be more sensitive to environmental changes than older children, given the younger individuals are in an important period for the development of myopia.’

Limitations

While the Feicheng-based study provided solid evidence of a link between time spent indoors and myopia’s severity and prevalence, the researchers were keen to emphasise that the results were limited by certain factors.

‘There were factors that we were unable to evaluate in this study,’ the authors explained, ‘including the adherence to school offerings, the exact amount of near work or screen time and the exact number of daily outdoor activity hours for each child. The lack of such information could limit the interpretation of the results of this study.’ However, the authors went on to explain that, because younger children were assigned less online work than older children, it was unlikely that rapidly progressing myopia in younger children was due to more intense screen time or near work.

They added that ‘the period of environmental change may be the main risk factor for myopia development, with the younger children more sensitive to the environmental change than the older children.’ Because of this, they said that the study suggests children aged between six and eight could be more receptive to myopia control measures, while older children’s eyes may resist treatment.