A s one of the country’s most recognised direct to consumer eyewear retailers, Cubitts felt the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent lockdowns more than most independent practices.

Cubitts founder Tom Broughton says the overnight closure of its practices, which provide 80% of the company’s income, meant going into survival mode. ‘Like a lot of companies, we saw a big spike in online activity, but it was nowhere near enough to offset the decline caused by the stores closing,’ says Broughton. Even as practices could later open as essential services, patients were limited to one at a time, which, for a company that relies heavily on footfall, was a devastating blow.

After the initial shock, Broughton says the company quickly refocused and only worked on what it could control. ‘We took the time to start improving bits of the business that were lagging behind,’ he says. ‘We invested a lot in our technology. We basically spent a year rebuilding and adding functionality to our site, which launched just before Christmas, and generally doing a lot of housekeeping.’

Despite the difficulties experienced by the company, Broughton says Cubitts ‘weirdly’ emerged stronger after the most severe restrictions lifted lasted year. But the precarious nature of the pandemic remains a threat to the business, as witnessed in late 2021 with the arrival of the Omicron variant. ‘As soon as Boris Johnson spoke about working from home and transmissibility, we saw footfall, sales, dispenses and tests just fall off a cliff. Business fell by 60% in the week before Christmas, but we’re just going to have to keep rolling with the punches for a bit longer I think, because this thing isn’t going away,’ he says.

Trying new things

The pandemic presented both challenges and opportunities for optical practices. For Cubitts, assessing the touchpoints with patients during their frame purchasing journey was crucial. ‘The critical part of the dispensing process, the final fit and collection is something that has been hard to do remotely, but we found ourselves forced into a situation where people still wanted to order but couldn’t come into stores,’ says Broughton.

A more nuanced fitting process was undertaken, with more measurements being taken at the eye exam stage so a frame could be adjusted for the patient before shipping.

Existing services also became more popular. Cubitts had offered frame refurbishment long before the pandemic, but the ‘rehab’ service gathered momentum during lockdown, Broughton tells Optician. ‘Rehab had always ticked along, and people love it, but often didn’t get around to it. We found that with people stuck at home, looking at themselves on screens for hours a day, they suddenly realised they could take advantage. The number of people using the service increases week on week, and we fully expect it to continue.’

Expansion

Since the company opened its first practice in Soho, London, in 2014, there has been a slow but steady increase in the number of locations. Primarily around London, but also into key south-east locations in Brighton and Cambridge.

Before the pandemic, Leeds had been identified as a potential location. ‘I thought we were very London-centric, but we knew anecdotally a lot of our customers would visit the store on trips to London from the north of England,’ says Broughton.

It was a case of waiting for the right location, but Broughton admits the company is very picky when it comes to choosing a premises. ‘We have 10 rules that every site has to adhere to. Everything from feel and type of building, to ancillary space, to look, not having a step when you go in, and not having cars parked outside.’

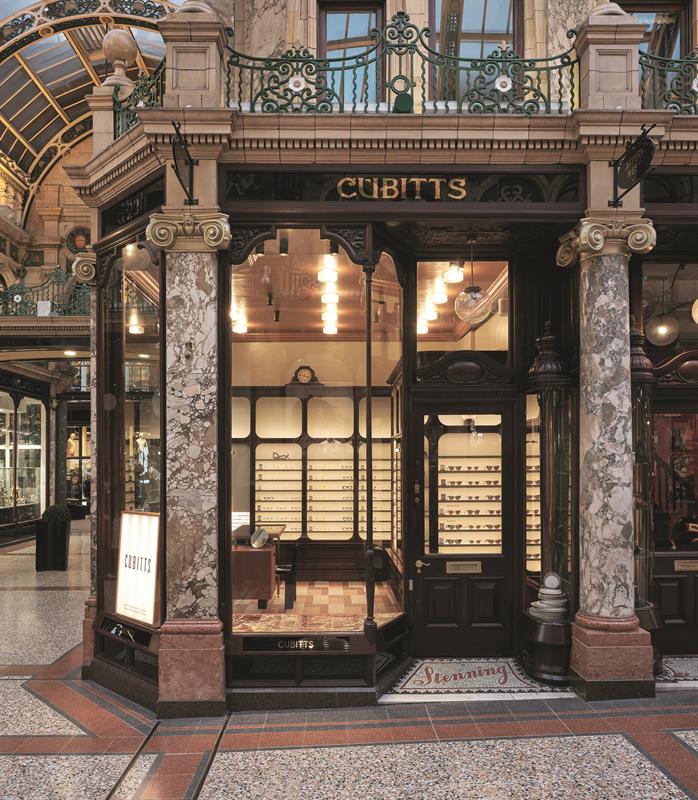

The new location in Leeds’ Victoria Quarter ticked all the boxes and was opened in November 2021, some two-and-a-half years after initially making an offer on the property. Even with the pre-Christmas Omicron downturn, Broughton is happy with how the practice is performing. ‘It has been brilliant so far,’ he says. ‘We introduced a whole bunch of local collaborations and designed a collection of frames, specifically for Leeds, to celebrate local history, which are really cool. The store also looks beautiful, which always helps,’ he adds.

The new Cubitts practice in Leeds’ Victoria Quarter

The new Cubitts practice in Leeds’ Victoria Quarter

Although the UK is experiencing a period of financial difficulty, other locations in the north of England, and even Scotland, are on the table for Cubitts. ‘We’d love to open in Edinburgh or Manchester,’ says Broughton. ‘We know from our existing customer database that we have really strong pockets in Edinburgh and Manchester, so we’d love to be in those places, but we’re not in a rush. I’ve been looking in Manchester for five years, but about when all the stars align, and we find the right location. We’d all rather wait for the right place, than rush it and try to force something through.’

Broughton adds: ‘But it’s worth saying, I don’t want loads of sites. We’ve got 12 now, soon be 13 and probably get up to 15 this year. But we don’t want 100. We don’t even want 50. We really want to preserve that sense of being fiercely independent and very service driven. We know from our customers that they’re willing to travel, so I don’t think we actually need that many.’

Crowded market

The number of direct-to-consumer eyewear brands has increased significantly in the past decade and accelerated further over the past five years. ‘When we opened in Soho seven-and-a-half years ago, we were the only branded optician or eyewear company, in the whole of Soho. There were one or two independents, and then there was a Vision Express on Oxford Street, but that was about it. Now, there must be 12 or 14, all in that same square mile,’ says Broughton.

Understandably, the increase in businesses operating in this space makes it harder for brands such as Cubitts to stand out, but Broughton thinks the saturation will lead to a correction in the next five to 10 years.

‘I think a lot of companies have entered the market having seen the success of Warby Parker in the US and then raised huge amounts of private equity and

venture capital money. Many of them will have then gone to agencies, put together a brand profile and then taken up retail deployment. But they haven’t really evolved that much and consequently, they end up feeling quite similar. I do think there’ll be a fallout and the ones offering something genuinely distinctive, with a stronger loyal customer base, will be the ones that survive,’ he says.

New direct-to-consumer brands are often labelled as disruptors. Is that a term Broughton feels suits Cubitts? ‘I would like to think that we’re innovators, rather than disruptors. I started the company with the idea of tackling some of the things that I was seeing in the industry, and I didn’t agree with from a customer point of view. I just thought that I could do better at some of the things.

‘We’re too small to be disruptive,’ he jokes. ‘I think our market share is 0.3%. We are an absolutely minuscule dot of a minnow compared to the big high street multiples. I’d like to think that we will have an impact that is wider than just us, but a positive impact on the industry and the consumer.’

The relationship between brands and how consumers perceive those brands is also changing in the wider retail sphere, something that could trickle down into optics. Broughton highlights a recent Nike announcement that the company will pull out of all wholesale accounts by the end of 2023 and shift entirely to direct to consumer stores and online retail. ‘That’s a big macro change, but to an extent and probably more slowly, it will affect optics and Cubitts is part of that.’

What remains traditional with Cubitts, is its approach to eye care. ‘We’re quite precious about the eye examination as a whole,’ says Broughton. ‘We don’t do free tests and they are 40 minutes long, with OCT available at some practices. Optometrists don’t have sales targets and only focus on clinical care,’ says Broughton.

‘I think the problem with free eye exams is it’s set an expectation in a consumer’s mind that, free doesn’t have value, which plainly isn’t the case and it’s an incredibly important clinical process that can genuinely save people’s lives and detect life threatening conditions. I do think one of the problems with the industry is that the eye exam has become a sales tactic all about getting people in and then upselling to them. It’s a bit like the pharmaceutical industry in the US, where important medical and clinical processes are conflated with sales approaches. Improving the patient’s perception of the importance of an eye exam is a good thing for everybody.’