On July 16, the Office for National Statistics released the latest figures concerning well-being among the population of Great Britain. With regard to mental health, they make uneasy reading. For all ages, the lockdown caused a peak in anxiety levels. Since then, anxiety levels have dropped again, but consistently remain higher than the pre-lockdown level (figure 1).

Well-being

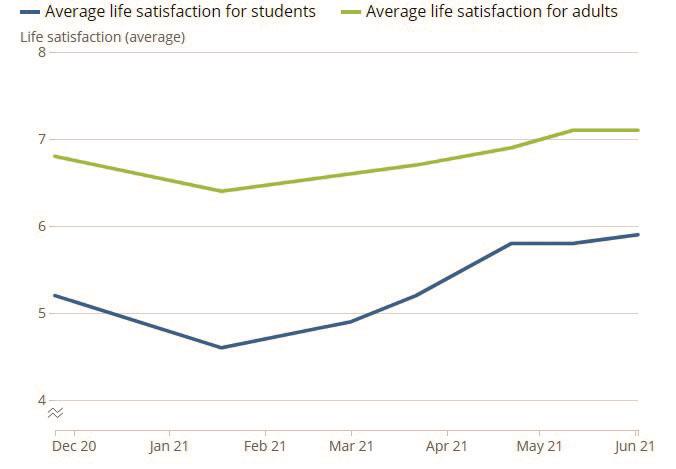

Matters related to well-being are assessed by the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey and so are subjective and determined by self-perception and sample selection. One set of data is based on the response from students about their ‘life satisfaction’. This is scored from 1 to 10 (‘not at all’ to ‘completely’) and the results show that the student population has scored significantly and consistently lower average satisfaction levels than adults since last December (figure 2).

Figure 2: Average life satisfaction for all students, England, November 2020 to June 2021 (ons.gov.uk)

Figure 2: Average life satisfaction for all students, England, November 2020 to June 2021 (ons.gov.uk)

Mental health

Less subjective data are based on diagnoses recorded by GPs and primary care. Unsurprisingly, when considering all diagnoses (mental and physical), the overall numbers correlate with age, with the greatest illness found in the over 75s. Also expected is a drop in diagnosis during 2020 because of the restricted access to health professionals.

When diagnosis of depression is selected, a different profile is revealed. The highest level of depression is among the 25 to 34-year-olds, some 215,564 diagnoses with a further 144,585 diagnoses in the under-25s. Remarkably, there is a significant (almost 2:1) female bias, which, I suggest, is more to do with women being more likely to seek help. This might also explain the worryingly high suicide rates among younger men and boys.

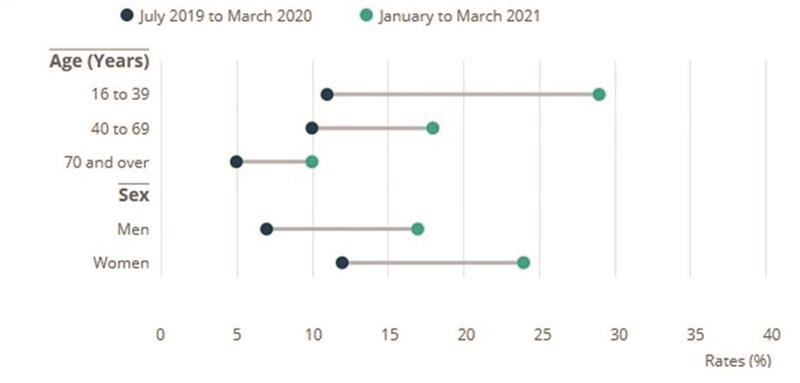

Since the start of the autumn 2020 term, almost a third (29%) of students said they had engaged with mental health and well-being services. The most frequently specified services used were GP or primary care (47%), online university services (40%) and NHS or Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme (29%). And younger adults, in general, appear to show the largest increase in rates of depressive symptoms in early 2021 when compared with pre-pandemic levels (figure 3). For adults aged 16 to 39 years, rates in early 2021 were more than double (29%) when compared with those before the pandemic (11%). In comparison, 10% of adults aged 70 years and over experienced some form of depression in early 2021 compared with 5% before the pandemic.

Figure 3: Changes in rates of depressive symptoms by age between July 2019 to March 2020 and January to March 2021 (ons.gov.uk)

Figure 3: Changes in rates of depressive symptoms by age between July 2019 to March 2020 and January to March 2021 (ons.gov.uk)

A thought

At present, a large proportion of the UK population is suffering some degree of mental health problem. Much of this might be alleviated with appropriate management. As lockdown restrictions ease, many patients will seek primary care services, including eye care. For some years now, many in low vision have argued for some involvement in the screening for depression and anxiety with a focused option for referral. Perhaps now is the time to consider whether we might have a broader role in recognising signs of mental health concerns in our patient base and be able to know what to do.

As details of the changes to ECP qualification are under scrutiny, surely now is the time to consider inclusion of some training in basic mental health screening as part of the ECP role? What do you think?

- bill.harvey@markallengroup.com