Case study

Patient initials: SC

DOB: 10/12/1999

Presentation: 24/07/2017

Reason for visit

Sudden onset of blurry vision in LE six days ago. Patient attended A&E who liaised with ophthalmology who requested a Band 1 EHEW assessment in our practice prior to being seen in secondary care. No pain, trauma, headaches, double vision, flashes or floaters were reported at initial assessment.

General health

Good, no systemic conditions or medication

Ocular history

This was their first sight test since childhood. No glasses or problems prior to this episode.

Family ocular history

No relevant issues

Lifestyle

Carpenter, driver, golf

Retinoscopy

RE Plano Clear reflex – no distortion

LE Plano / -1.00 x 90 Clear reflex – no distortion

Refraction

Vision Refraction VA NVA

RE 6/6 Plano / -0.25 x 80 6/6 N5

LE 6/120 +0.25 / -1.00 x 90 6/120 N24

Pupils

Normal DCN, PERRLA – No RAPD

Ocular motor balance

Orthophoric on cover test distance and near

Amplitude of accommodation

+10DS R and L and binocular

Amsler

RE Areas of distortion surrounding fixation

LE Central scotoma and peripheral distortion

Anterior assessment

VH Grade 4 – wide open

Eyes white and quiet R&L

No corneal scarring, staining or deposits

Lens clear with no opacities

Central corneal thickness

RE 478µm

LE 483µm

Goldmann Contact Tonometry

RE 11mmHg LE 8mmHg

Posterior assessment (with dilation)

Vitreous

Clear no significant floaters or evidence of vitritis

Optic discs

RE CD 0.4 LE CD 0.3

Healthy well-defined margins R&L

Healthy NRR R&L

Moderate Cupping R&L

ISNT obeyed R&L

Vessels

Normal A/V ratio of 2:3 R&L

Peripheral fundus

Normal with no breaks or tears or evidence of retinal detachment

Right macula

This shows several irregular semi-defined lesions of just less than one disc diameter (DD) in size. These cloudy lesions are of uneven colour with areas of both hypo and hyper pigmentary pigmentation. The central fovea appears essentially clear (figure 1).

Figure 1: Posterior pole, right eye

Left macula

This shows several lesions of similar appearance to the right eye (figure 2). However, there is also a ½ DD-sized lesion at the central foveal location which would explain the profound, sudden loss in VA.

Figure 2: Posterior pole, left eye

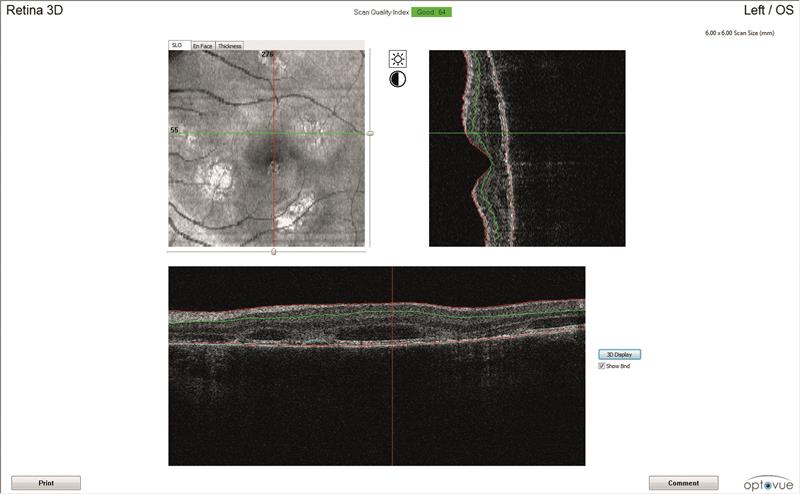

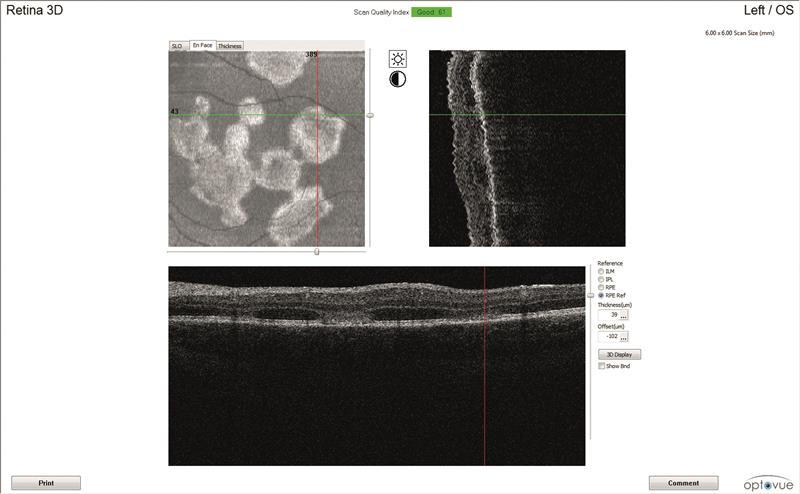

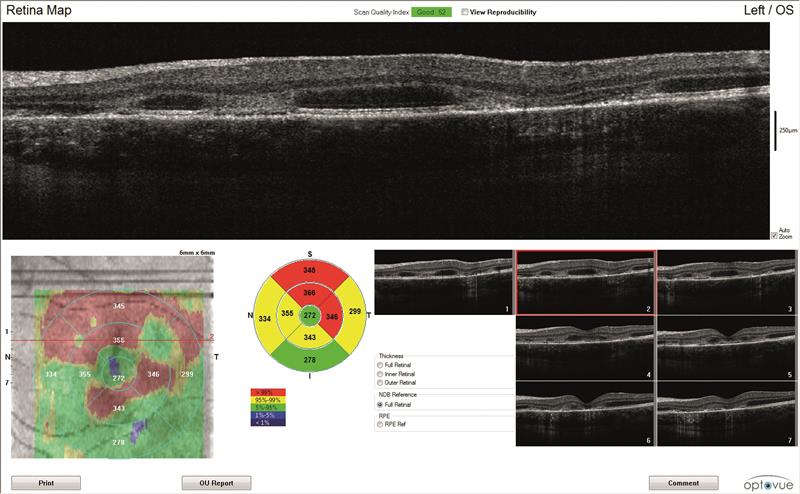

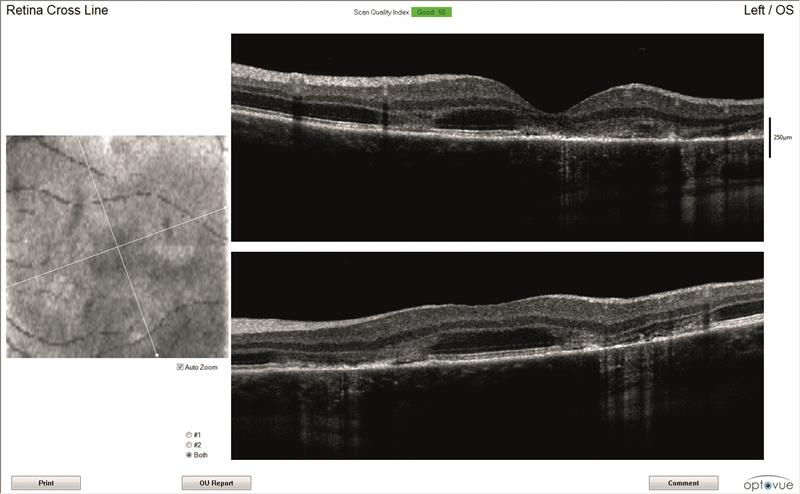

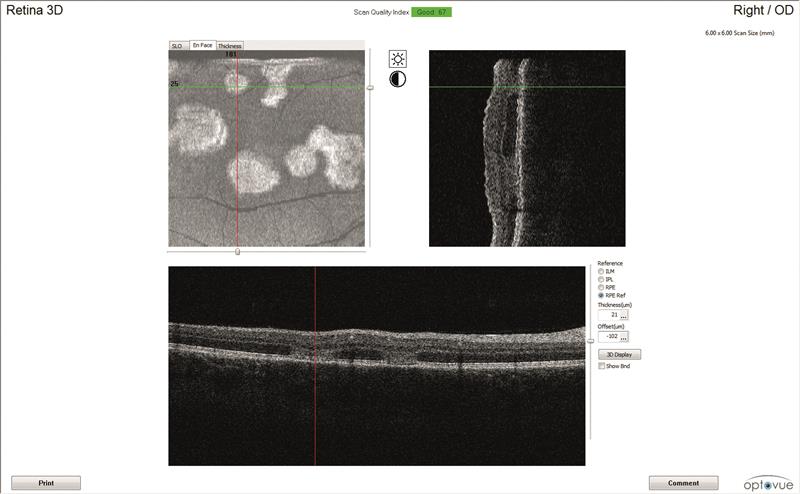

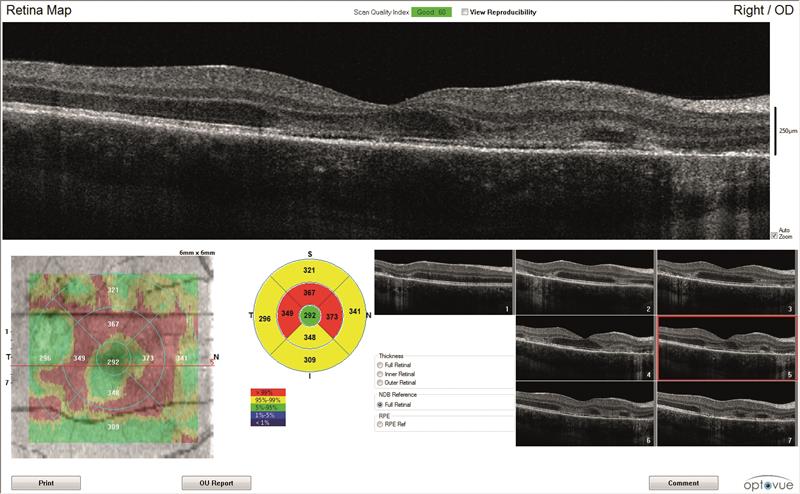

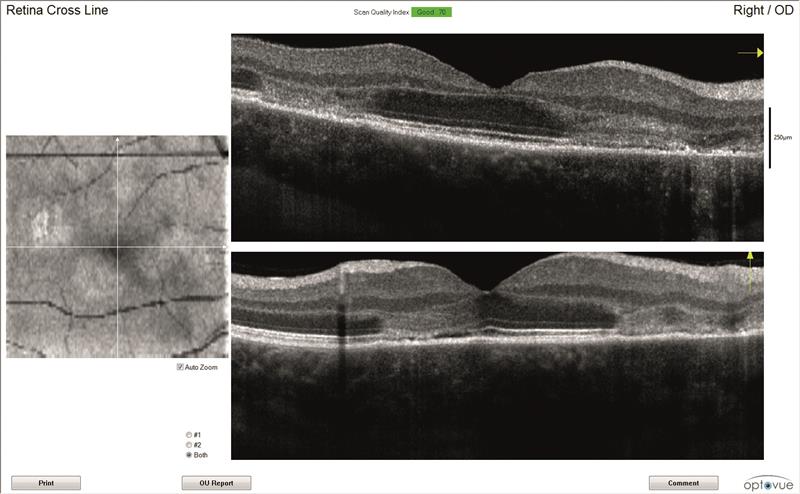

OCT scans (figures 3 and 4)

Both maculae have large cystic spaces with photoreceptor disruption and evidence of RPE scarring and increased retinal thickness. The en face images show the defined areas of damage quite well.

3A

3B

3C

3D

Figure 3: Left eye OCT scans. a) 3D scanning laser ophthalmoscopy image, b) en face report c) retinal thickness map, d) line scan

Action

Due to the recent onset of symptoms and the sudden dramatic loss of vision in the presence of bilateral pathology, the local eye department was contacted to arrange an urgent assessment in a macula clinic. This was requested as I felt that a fundus fluorescein angiogram (FFA) might be required. In my referral, I highlighted the bilateral nature of the presentation despite uniocular symptoms.

I suggested a tentative diagnosis of active bilateral chorioretinitis. I had initially thought that the right eye presentation and lack of symptoms might indicate a more chronic white dot type syndrome that was going through an active phase. An emergency appointment was confirmed in the macula clinic two days hence.

The patient was seen and initially treated with prednisolone (30mg per day) and Co-trimoxazole. This is an antibiotic consisting of a one to five mix of trimethoprin and sulfamethoxazole as toxoplasmosis was considered a possibility. The patient underwent extensive blood tests, and at a one week follow up the clinic reported that serology had come back negative for toxoplasmosis. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level was normal and a basic auto-immune screening proved negative.

It had been noted that the clinical picture seemed to be improving with the steroids and that the serology indicated that the Co-trimoxazole was no longer required. The patient was therefore advised to stop this but to continue taking the steroids.

4B

4C

Figure 4: Right eye OCT scans.

a) en face report

b) retinal thickness map

c) line scan

Additional comprehensive blood tests were ordered, including VDRL (this is the ‘Venereal Disease Research Laboratory’ test for syphilis). Screening for Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster alongside HIV, Lyme disease and cytomegalovirus tests were requested to eliminate a posterior uveitis from any of these causes. Specific HLA-B7 and HLA DR-2 tests were also requested.

The conclusion of this second appointment was that the diagnosis was a simple chorioretinitis at this stage. A further appointment was made for FFA and review in two weeks during which the dose of 30mg prednisolone continued daily.

The blood tests from the second review showed that the patient had tested positive for HLA B7 and HLA-Dr2. The FFA had shown an early blockage and light staining. At this stage a more specific diagnosis of acute posterior multifocal placoid epitheliopathy (APMPE) was made.

The initial inflammations were starting to settle and the creamy retinal pigment epithelium lesions were being replaced with hyperpigmentation and atrophy. The left acuity had improved to 6/24+ (with pinhole) from the 6/120 found at initial presentation. The patient was advised to keep taking the prednisolone (30mg daily) for a further month prior to clinic review, the results of which were not available at the time of writing.

The concern with this condition, once the initial acute phase has resolved, relates to the increased possibility of choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) developing.

Discussion

This case is interesting as it shows the difficulty even for hospital doctors in making a 100% accurate specific clinical diagnosis on initial presentation. To me, the most interesting element of this case was the correlation with both the initial treatment and the vast barrage of blood tests ordered which give an indication of the multitude of potential causative agents in chorioretinitis.

Blood tests

Here are some details of blood tests taken for this patient.

Serology

Looks at inflammatory markers and antibodies in the patient’s own blood serum, specifically for toxoplasmosis which is one of the most common causes of choroiditis in younger people. Lyme disease was also excluded at this stage.

C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

This is a blood test looking for a protein in blood plasma whose levels rise in response to inflammation.

Auto-immune screening

This looked for:

- ANA – Anti Nuclear Antibodies: These can identify the following. Note, the specificity of this test is not perfect as it is quoted that 95% of patients who test positive for SLE will not have lupus. However, 95% of patients with lupus will test positive for ANA.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Sjögren’s syndrome

- Scleroderma

- Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA)

- ANCA-associated vasculitis

- Polyangitis

- Churg Strauss Syndrome

- Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE)

- Levels of this enzyme will often be raised in sarcoidosis

These are all markers for autoimmune/inflammatory or infective causes of chorioretinitis. The further tests ordered (looking at HLA B7 and HLA DR2) are specific tests that can be positive in patients experiencing inflammatory episodes which have frequently been linked to episodes giving rise tochorioretinal inflammation.1

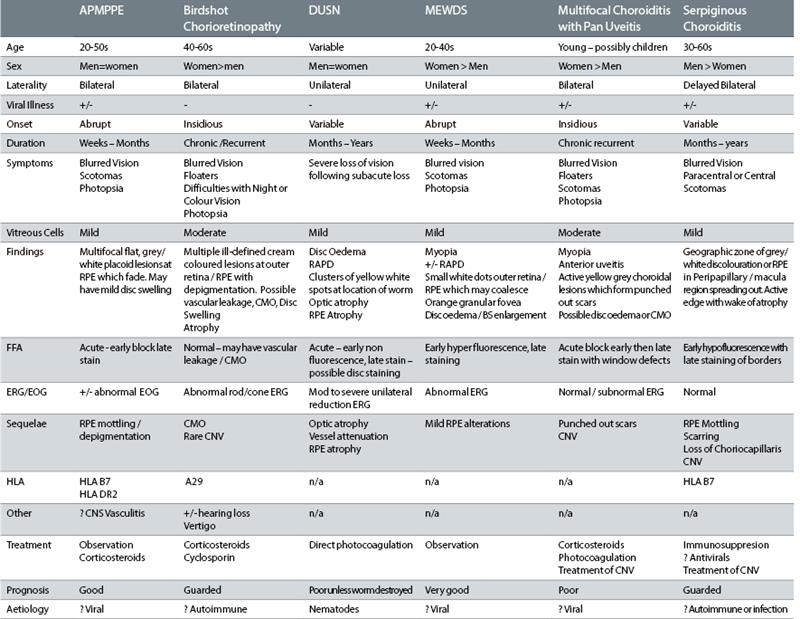

APMPPE is one of a group of conditions known as the ‘white dot’ syndromes which would also include birdshot chorioretinopathy and serpiginous choroiditis, multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS), multifocal choroiditis and pan uveitis, punctate inner chorioretinopathy (PIC) and diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis (DUSN).

As a group, they often present with multiple whitish yellow lesions at the level of outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium and choroid. APMPPE is typically found equally distributed between men and women, is bilateral and abrupt in onset. The condition may follow a recent viral illness, though a definitive link is not yet proven. Mild vitritis is often recorded, and though I had not noted this, the consultant has referenced their presence.

The FFA showed early blockage and light staining which are classic features of the disease. If the local eye department had access to indocyanine green angiography (ICG), then hypofluorescence of both active and healed lesions would have been likely due to a disruption of the normal choroidal perfusion.

The formal aetiology is not understood, but links to recent viral illness and an associated vasculitis may be implicated. Associations with sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, colitis and Lyme disease, HLAB7 and DR2 have all been made and explain the battery of blood tests ordered by the managing consultant.

Table 1: Common white dot syndromes (adapted from Quillen et al2)

A very small number of reports have been made identifying the development of a central nervous system vasculitis within several weeks of the acute phase of APMPPE, and so patients with headaches or other neurological factors need to be considered for MRI assessment.2

The visual prognosis will be dependent on the degree of central scarring. Recurrences have been noted to be rare and the larger risk is associated with the development of a CNV. In this case, the use of steroids seems to have been precautionary and the efficacy of this treatment is not proven.

Most optometrists are confident and competent at diagnosing anterior inflammatory conditions (such as iritis), but posterior affecting diseases are encountered much less frequently and our exposure to this group of conditions is much more infrequent.

The more widespread availability of practices to undertake OCT screening will facilitate accurate diagnosis, and the bilateral acute nature of this presentation would have led someone well versed in the appearance of white dot syndromes to identify APMPPE as the most likely diagnosis.

Table 1 shows the differential features of the most common forms of white dot syndromes.2

Andy Britton is an optometrist and co-director of Specsavers Haverfordwest in South Wales.

References

1 Wolf MD. 1990. HLA-B7 and HLA-DR2 Antigens and Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy. Archives of Ophthalmology 108(5), p. 698.

2 Quillen DA, et al. 2004. PERSPECTIVE The White Dot Syndromes. American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea 137(3), pp. 538–550.

Do you have an interesting case?

Look out for a second series of case studies from Andy Britton towards the end of next year. If you are interested in us publishing one of your more interesting cases, please contact clinical editor on bill.harvey@markallengroup.com. We will pay £250 for every case we publish. Full editorial support is provided.