As Arsenal and Manchester United prepare for tomorrow's FA Cup final in Cardiff, David Baker asks whether the colour of a team's kit can affect performance.

As Arsenal and Manchester United prepare for tomorrow's FA Cup final in Cardiff, David Baker asks whether the colour of a team's kit can affect performance.

The team colours of individual football clubs have many, often arbitrary or obscure, roots. For instance, the Italian Serie A club Juventus changed to black and white stripes in 1903 because an order for shirts placed with an English manufacturer was mistakenly made up in Notts County's colours. But it can be fairly stated that vision-related factors have probably not often entered into the equation. Given that fine margins can determine success or failure in modern professional sport, perhaps this issue now deserves deeper consideration. This article aims to discuss some aspects of football strip design.

The grey factor

The topic of football shirt colours came briefly to prominence in 1996 when both England and Manchester United used grey strips. One of the reasons, particularly in the Football Association's case, for the innovation was the growing popularity of football shirts as leisurewear. It was felt that grey, a neutral colour, would blend in well with jeans and other casual clothing. While logical in a marketing sense, this was exactly the reasoning that made grey a poor choice for a football strip: the United players complained after a 3-1 defeat at Southampton that they had difficulty picking out team-mates.Southampton may have something to say about the reasons for that result, but the United players' excuse may have some merit. It has been shown that a 'soothing' colour such as grey tends to be ignored by the peripheral visual system, so bright colours and strong contrast between the colours of a pattern (such as stripes) are preferable for good visibility1 - one reason why referee's assistants' flags are yellow and orange. Also, with around 8 per cent of males having some form of colour deficiency, there is a fair likelihood of at least one out of the 36 players and officials potentially involved in a professional match being affected. And for a strong red-green deficient, red can be mistaken for grey. In any case, grey shirts tend to blend in easily against the background of the crowd; a situation exacerbated for a myopic player with somewhat reduced contrast sensitivity.

These factors could indeed affect a player's performance. Significant visual and mental energy is required during a game for interpreting tactical situations and for controlling and playing the ball. Fatigue, which is inevitable as the match progresses, will occur sooner if vital time and energy is diverted to ascertaining the team and position of other players due to their being less obviously visible. As a result, decision-making is impaired.

There are also psychological aspects of colour choice inasmuch as, just as grey is considered 'soothing', other colours can be associated with, or promote, particular moods (eg red: strength, aggression). Many players are notoriously superstitious, something that should not automatically be ignored. For instance, the Jamaican national team, which plays in yellow and black, suffered a player revolt in 1998 after a change of shirt manufacturer and design.2 Their first game with a new strip coincided with a 6-0 defeat, so the players demanded a return to the old, now defunct, strip until a compromise could be reached with the manufacturer.

An historical perspective

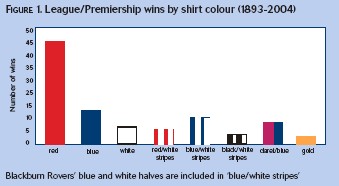

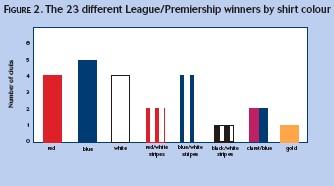

Is it possible, then, to gain any insights about 'successful' colours by looking at clubs' past achievements? The period 1893-2004, allowing for suspension during the two world wars, saw 100 seasons of competition in the top division of English football. The winners can be broken down by their predominant shirt colours as shown in Figure 1. This shows that red is comfortably in the lead with 46 wins and blue (sky, royal) a distant second on 14 wins. However, those 46 red wins are shared among only four clubs (Figure 2); only 23 different clubs having won the entire 100 championships. This seems to illustrate what might already seem common sense; that a football team's success is primarily down to such other factors as resources and choice of playing and coaching staff rather than the colour of the shirt.Had the 46 red wins been shared among many clubs, the colour factor might carry greater weight. It is unlikely, in any case, that a club would lightly change its colours - considering the connotations of history and tradition - for a small theoretical advantage. Still, during the formative years of many clubs, several changes of club colours were common until a regular scheme was settled upon. Manchester United/Newton Heath's green and yellow halves, recently revived briefly as a third strip, is one such example.

Second strips

There certainly could be scope for experiment with second, or change, strips. Professional clubs have one, if not two, change strips for use at away matches when their normal colours would clash with those of the home team. The choice of second and third strips traditionally would still have some association with the club's colours, sometimes being a straight reversal of first strip shirt and shorts colours. Nowadays this linkage is often much looser or absent altogether, with aesthetic and marketing considerations becoming paramount. It can, of course, occasionally go wrong, as anyone who remembers Coventry City's notorious all-chocolate strip of the 1980s must agree.Since the win-ratio of away teams is generally much lower than that of home teams, any additional advantage to be gained by a judicious choice of second strip, however small, is surely worth looking at. A bright colour together with strongly contrasting stripes, as mentioned previously, could be a starting point; the ideal being yellow with black stripes. Indeed, David Pleat, until recently director of football at Tottenham Hotspur, has indicated that a second strip with a design chosen for improved visibility has been a topic for discussion at board level.3

Clubs and their kit manufacturers are constantly trying to come up with new twists to traditional themes in order to sell more 'home' shirts. With kits being changed every two to three years, there is only so much that can be done to tweak designs within the parameters of clubs' colours. Second and third strips appear to provide more opportunities for experimentation and there is no reason why visual, as well as aesthetic, imperatives could not be addressed together. The short-lived experiment with grey, however, is unlikely to be repeated for a good while.

References

1 Cockerill I. Scientific evidence that Grey strips may have lost England the European cup [sic]. Sports Vision Association Newsletter 2: 3, October 1996.

2 Baker D. Favorite Shirts. Matchday (USA) 4: 19, May/June 1998.

3 Pleat D. Personal correspondence with Baker D, April 2001.

- David Baker is an independent OO who writes on optical matters and on sport