An interesting case was brought to my attention recently; in which the abnormal finding had nothing to do with the reason for the eye examination. These ‘surprise’ findings can easily disrupt our day and add considerably to decision making and patient interaction.

In this case, a 53-year-old gentleman was seen by his optometrist four weeks after routine cataract surgery. The patient was happy with his vision, which had improved from 6/12 to 6/5 and all the usual checks, including wound healing, pupils, quiet anterior chamber, centred IOL and healthy macula, demonstrated no operative or post-operative complications. It wasn’t until the optometrist examined the peripheral retina that anything out of the ordinary was found – figure 1.

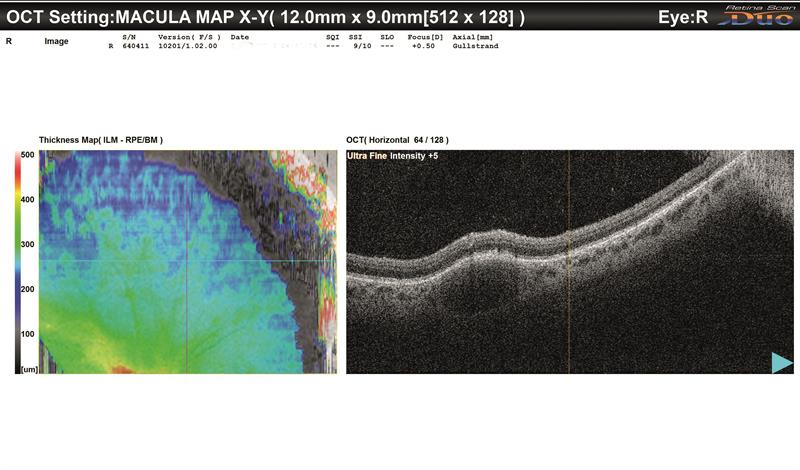

Clearly an abnormal finding and enough to worry many practitioners. The first thing to avoid is jumping to quick conclusions; for any given signs there are generally a handful of potential causes, so describing the characteristics you see first alongside any symptoms the patient is having can help organise your thinking. Here, I would note this as a slightly raised (confirmed by the OCT B-scan in figure 2), pale non-pigmented lesion, no more than two disc diameters in size in the superior mid-peripheral retina and with well-defined margins. There also appears to be the faint stippling of drusen present within the lesion and if you recall, the patient was asymptomatic. So the top two lesions we have in our minds are amelanotic choroidal naevus or amelanotic choroidal melanoma.

Figure 2: OCT B-scan of retinal lesion: The boundaries of a mass in the anterior choroid can be clearly demarcated, causing the retinal elevation above it. No sub-retinal fluid is present

Figure 2: OCT B-scan of retinal lesion: The boundaries of a mass in the anterior choroid can be clearly demarcated, causing the retinal elevation above it. No sub-retinal fluid is present

The prognosis for these lesions couldn’t be further apart: a choroidal naevus is a benign melanocytic tumour with a prevalence in the over 40s of approximately 5%1 with just under one in 9,000 cases mutating to develop into a melanoma,2 while a choroidal melanoma is a serious life-threatening intraocular malignancy at risk of metastatic disease, most often found in caucasians with annual incidence of around four cases per million.3

So how do we tell them apart? Remember you are not alone – it’s more important that you know where to look up relevant information or who to seek it from than to know everything yourself.

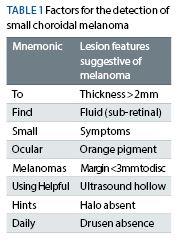

Research into risk factors for melanoma has enabled high-risk features to be grouped as a mnemonic – To Find Small Ocular Melanomas Using Helpful Hints Daily4 – to encompass all the key features.

In the UK, evidence-based recommendations exist to assist us in our decision-making process. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists advises referral to one of the Centres of Excellence for adult ocular oncology in Liverpool, London, Sheffield or Glasgow if the suspicious choroidal lesion has any one of the following features: thickness greater than 2.0mm; collar-stud configuration or documented growth, or any two features of thickness >1.5mm, orange pigment, serous retinal detachment or symptoms.

The College of Optometrists advises that the key high-risk features which would indicate urgent referral (within one week) to an ophthalmologist are a documented increase in size (especially thickness); symptoms; sub-retinal fluid; location within two disc diameters of optic disc or clumps of orange pigment on the tumour surface. Importantly, this action should be following a telephone discussion with an ophthalmologist.

Looking to apply these features to our case, the OCT scan indicates the thickness to be around twice the retinal thickness (and therefore less than 1mm), with no fluid, no symptoms, no orange pigment with a margin greater than two disc diameters from the disc (and therefore unlikely to be less than 3mm from it) you can see we are dealing with a lesion failing to display any high-risk features – therefore not for referral but (according to the College of Optometrists), requiring regular surveillance. Great, we can breathe a sign of relief for the patient. However, here is where the research and professional advice dries up somewhat in not stipulating what is meant by regular surveillance. Casting the advice net a little wider reveals a general consensus among ophthalmological colleagues that optometrists are perfectly placed to monitor low risk naevi annually. For those without access to any type of ocular imaging, to me it seems prudent to obtain good baseline imaging through routine referral to the

ophthalmologist.

This case highlights that we shouldn’t be too surprised to find an abnormal finding lurking in the eye – after all that’s what we are all trying to rule out at every eye examination – but also demonstrates that evidence is what lies beneath strong clinical decision making – giving us confidence that we are doing our very best for our patients.

Tim Manners, consultant ophthalmologist and Newmedica Ophthalmology Joint Venture Partner, Lincolnshire.

References:

Royal College of Ophthalmologists Clinical Guideline. Referral Pathways for adult ocular tumour (March 2019) Available online from https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/...

College of Optometrists Clinical Management Guidelines: Pigmented fundus lesions (Version 1 2017) Available online from https://www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/clin... -guidelines/pigmented-fundus-lesions.html

More references available at opticianonline.net

1 Qiu, M & Shields, C (2015). Choroidal Nevus in the United States Adult Population. Ophthalmology 122(10);2071-2083

2 Singh AD, Kalyani P, Topham A (2005) Estimating the Risk of Malignant Transformation of a Choroidal Nevus. Ophthalmol 112(10);1784-1789

3 Singh AD, Topham A (2003) Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1993-1997. Ophthalmol 110:956-961

4 Shields CL, Cater J, Shields JA (2000) Combination of Clinical Factors Predictive of Growth of Small Choroidal Melanocytic Tumors Arch Ophthalmol 118(3):360-364