You do not have to go far in contact lens practice, or indeed general optometry, in the UK these days without bumping into myopia management (or MM, the preferred term for myopia control these days). The concept inspires strong support from passionate enthusiasts, with wilder claims that the scourge of myopia is so significant that MM should be NHS funded and that practitioners who fail to offer or advise MM are potentially negligent and harming their patients.

There are, of course, solid reasons to be passionate about MM. Reducing the prevalence of high myopia with an intervention as commonplace as fitting contact lenses is to be thoroughly recommended.1 That said, some parts of the scientific picture remain somewhat blurred and will only likely come into focus as time progresses. However, we now know enough to influence any decision not to do something where we might have some impact.

The passionate, positive claims from the early adopters often fall on the deaf ears of the majority yet to embrace MM. ‘It’s all very well for you in academia, but does the business case stack up in a community practice? And more to the point, does it really, truly, actually work?’ Well, who better to answer such questions than us canny Scots, known for our unflinching commitment to finding reasons why new ideas should be rejected and for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory?

In this article, I hope to present the unvarnished truth about MM based on our experience in practice – warts and all. I will mention successes, failures, the good, the bad and the ugly as I look back, having this year reached a milestone of treating over 50 patients with MM. This represents over 1,000 patient months of wearing MM lenses. Neither Cameron Optometry (our practice) nor any of our optometrists have any financial interest in MM or any related product, although we have given some lectures and written some articles for some of the companies involved.

Background

Cameron Optometry is a large independent contact lens and therapeutics specialist practice in the centre of Edinburgh, with a team of five optometrists and 12 support staff. Despite offering specialised services, the bulk of the practice is ordinary community optometry with ordinary paying punters, so absolutely not the rarefied atmosphere of a research department or industry lab.

Our first official fit for MM was in August 2015, and with targeted marketing and patient education, we have steadily increased over the years to have more than 50 people currently wearing MM lenses on an ongoing basis. Details of the service provided have been discussed before,2 and details of the success and failures of our strategy to increase awareness in the local area will be the subject of future articles.

The Patients

Our MM patients are as follows:

• Females <17 years: 27

• Males <17 years: 21

• Total number of patients fitted with lenses for MM: 65.

• Number of patients age 17 or under wearing MM lenses regularly: 48

• Number of adults wearing lenses for MM: 3

• Average starting age of successful non-adult wearers: 11.4 years

At the time of writing, we have fitted 65 patients with MM lenses with 51 continuing in the longer term with the lenses. As expected, the vast majority (94%) of these are under the age of 17 years, with the average age being 11.4 years.

There are three adult patients with progressive myopia who have also been managed. These are:

• A 22-year-old woman in Ortho-K

• A 20-year-old woman in MiSight

Recruitment to MM is primarily through discussion with myopic parents during their eye exams as well as the detection of progressing myopia in our younger patients. However, it was really through targeted marketing in the early days that we managed to build numbers. This, in turn, help to build practitioner confidence and allowed the service to grow. As the service has matured, we have found patients seeking us out directly through recommendation from both patients and other practitioners.

The Treatments

The different MM treatments are as follow:

• Orthokeratology 17

• Biofinity MF (CooperVision) 9

• Mylo (Mark’ennovy) 1

The choice of method for MM is multifactorial; we are shaped as much by our habits as by what is in vogue at any time in history. Back in August 2015, the only option was Biofinity MF soft lens fitting. Orthokeratology (OK) was not part of our practice at that time. It was the planned move into providing an MM service that led us to set up our OK service and the uptake has been significant. Indeed, we may have struggled with MM without being able to offer this option. Other products, like Mylo and NaturalVue (vtivision), have since been fitted but have not formed a significant part of our dataset yet.

Recognising the benefits of contact lens wear for children, and appreciating the greater efficacy of contact lenses in myopia management modalities compared with spectacle lenses in the majority of patient groups,1 our tendency has been to recommend contact lenses over spectacle lenses. That said, one eight-year-old avid reader of -3.00DS, with a very myopic mum (-8.50DS), was dispensed with progressive addition spectacle lenses. She had an accommodation lag and near esophoria and had found contact lens handling very difficult. She tolerated the spectacle lenses well but, after one year of wearing them, continued to progress. So, after discussion with her family, we decided to go back to single vision lenses.

We always mention the future possibility of medical treatments, like atropine, and keep patients abreast of the latest research, like the CHAMP study currently ongoing throughout the UK. Despite us not offering or recommending atropine treatment, this has not prevented at least one patient’s parents from sourcing atropine from a clinic in Italy and administering it to their child.

The Outcomes

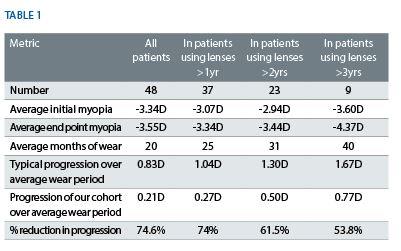

- Myopic progression is reduced significantly in children under 17. See table 1.

- All lens types reduce progression in line with published research.

The Failures

Patient details of those failing with MM include:

• Average starting age of non-successful wearers – 10 years

• Average starting age of those who dropped because they were not keen or struggled with handling – 8.9 years

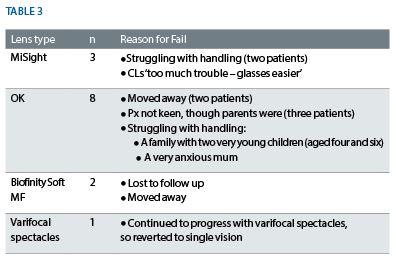

In total, 14 children dropped out of MM lenses. At an industry-wide level, a 20% drop out rate is fairly reasonable, particularly in a younger aged population. However, contact lens dropout rates at our practice have been studied carefully in the past3 and are typically nearer 10% and so the dropout rate in MM is roughly twice as high as average in our practice.

Difficulty in handling the lenses was a significant predictor of dropout. This is similarly a strong reason for dropout in a general contact lens wearer population and we have invested heavily in our teaching/handling methods to reduce this as much as possible. The staff undertaking MM handling training are extremely experienced with children, and we have invested in transforming the handling room into a calm, bright and uncluttered space. It includes comfortable furnishings and patients are never disturbed during the process.

Additionally, our staff have qualifications in the management of childhood anxiety and play-based learning. This helps them to better understand and work with children during the teaching process. Staff are allowed unlimited time with the patients, some of whom require a significant investment in training. Anecdotally, most children take one to two teaching sessions, rarely more than three, though there was a couple of exceptional cases needing up to five sessions before we would allow them to take their lenses away to try at home. Therefore, we feel we have evolved our handling/teaching as far as is possible, but still have twice the number dropping out because of this.

A related factor is the patient’s motivation for wearing contact lenses (CLs). Our practice is experienced in fitting CLs to children and, in our hospital work, to babies with aphakia. MM children, however, might be the first group we have dealt with where they may be less motivated to try contacts and are yet ‘forced’ to do so. We have always adopted the approach that, where a child did not want to wear contacts, we simply would not fit them – even where the parent was keen for various reasons. MM represents a shift in paradigm, where a child may not be keen but both parent and practitioner feel it is in the child’s best interests to be fitted. They therefore may have to be encouraged to persevere, somewhat against their will.

In our experience, the lack of motivation to wear, or indeed fear of, CLs is often overcome once children get the hang of them. They soon appreciate the specific advantages of correction in their daily life. That said, there are some cases where, despite our best efforts, this has not occurred and fitting has been abandoned altogether. Other times, children have learned to use the lenses successfully but still prefer not to wear them. We have found these patients to be likely dropouts after a few months of on/off wear, often after some battling with mum and dad. This seems to be closely correlated to younger age.

This is a new paradigm for us, and learning to manage concerned parents who wish for their child not to ‘end up like me’ with high myopia has been a learning curve for us. It certainly appears that young age is correlated with increasing levels of failure, most often due to handling. Having said that, our youngest patient who handles contact lenses competently without assistance is just five years old.

The Lessons

There are various lessons we can draw from the data but here are some of the stand outs:

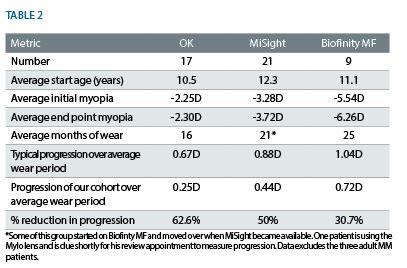

- MM actually does work in real life and in a non-study setting. We now have our own data on 48 patients that shows that our rates of reduction in myopia progression are very similar to those in the current literature. In fact, it is scarily similar. The IMI guidelines suggest a 30 to 60% efficacy with OK and 30 to 50% with multifocal soft CLs.1

- OK is more effective than the use of soft lenses, again in keeping with the research.

- We have a higher drop out of OK patients than those using MiSight. However, we typically try OK lenses with patients who are younger or who we presume may struggle with handling soft lenses, and so the younger age may impact upon the dropout rate as previously discussed.

- No patients who tried the lenses dropped out because of the multifocal visual effects of the lenses, but rather because of more general contact lens issues such as handling.

- In general, younger age (less than nine years) and, particularly, lack of personal initial motivation for CL despite parental support are the strongest indicators that a child will drop out. Older children seem to be able to overcome such anxieties in many cases.

- We have been promoting MM as hard as we feel we can alongside all our other competing focuses as a practice, and have fitted 50 people in almost exactly four years – which is roughly one person a month. When averaged out like that, it is hardly a remarkable figure given the effort we have gone to in setting up and refining the service. However, it is our hope that such a critical mass of patients means we are well positioned to ride the tsunami of myopia cases the experts tell us is heading our way in future. On average, we fit around two new private patients with contact lenses per week, and so MM represents a little over 10% of our new fits each month. In retrospect, it does not feel like there was a whole lot more we could have done to promote and advertise our service and so perhaps this figure of ‘10% of your new fits’ fairly represents the true level of interest in a normal population at the moment. Of course, others may be doing better than we are.

The Limitations

Clearly, these data are not derived from a well-controlled academic study and so should be understood only for what they are. These patients were primarily fitted with lenses because it was felt this was in their best interests. We kept what information we could manage in the midst of a busy practice so we could eventually audit the outcomes, but we had no intention of analysing the data in any statistically robust way, and there are inaccuracies throughout to be sure.

We have got better at considering and recording binocular vision factors, such as accommodation lag and near muscle balance, only recently and such data would be a valuable addition in analysing these outcomes.

Similarly, although we always discuss time spent outdoors by a patient and give out general advice leaflets on reducing the risk of developing myopia, this is not recorded in any robust, numerical manner which would allow incorporation into the report in a meaningful way. We are trying to improve, but the constraints of general record keeping and running a busy practice mean that such ‘additional’ metrics are the first to be overlooked.

The Future

From the start, we wanted our recommendations for MM to be borne out of the best available evidence and we have been committed in our discussions with patients to be rigorously honest about what we know, what we do not yet know, and expected outcomes.

We are glad to find that MM works and so we can recommend it more confidently. The science behind it is robust and borne out by our day to day practice.

What we have discovered is that there is a clear business case in terms of patient loyalty, patient recommendation and pure profit in undertaking this intervention. However, promoting the service and managing the increased time required to teach and work with young children in contact lenses is significant, and uptake has not been huge.

Like everyone involved in MM, we await the results of CHAMP with bated breath.4 If atropine is demonstrated to be effective, safe and well tolerated, and assuming an appropriate dose preparation is easily and legally available, we suspect that there will be a large number of patients keen to try this approach; either in addition to, or in preference to, contact lenses. As seen by the relatively high drop out rate in MM, there is a cohort who are motivated to intervene in their myopia but find the high bar of contact lens wear simply unassailable. It seems logical that a far easier intervention (like atropine) will be popular with such a group, and could be the factor that leads to wider MM recommendation and uptake.

It is certainly true that myopia is on the rise and becoming an area of interest to policymakers outside of optometry, and our profession would do well to prepare to be at the forefront of this preventative eye healthcare wave. This wave has not quite hit yet. Until it does, our experience with MM shows that it can still be interesting, financially rewarding, and that it really does work.

Ian Cameron is an independent therapeutic optometrist based in Edinburgh.

References

1 IMI – Interventions for Controlling Myopia Onset and Progression Report. IOVS, Special Issue, February 2019

2 Gillian Bruce. Why you shouldn’t be terrified about myopia management. Optometry Today, Jan 18, 2019.

3 Cameron I. The Dropout Challenge. Presentation, BCLA Clinical Conference 2015.

4 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03350620