Recently, reflective practice has taken centre stage in many new healthcare-related continuing professional development (CPD) schemes including those introduced by the UK General Optical Council (GOC) in 2022, and the CORU Optical Registration Board in Ireland in 2019 (the name CORU originates from an Irish word, ‘cóir’, meaning fair, just and proper). Reflection enables practitioners to view situations from different perspectives.

The GOC, for the first time this year, requires dispensing opticians to reflect on a peer review with professional colleagues in line with the requirements for optometrists and contact lens opticians that has existed for many years.

Eye care practitioners (ECPs) are encouraged to reflect on all CPD activities and in the UK the GOC identifies two different reflections to be undertaken:

- A reflection statement; this must be completed for all peer review and self-directed CPD activities, and ECPs are recommended to complete them in relation to all CPD that they do as a matter of good practice.

- A reflective exercise; this is a new requirement that GOC registrants will complete for the first time in the last six months of the current CPD cycle prior to the end of December 2024.

When logging a CPD activity, ECPs can either complete a short-written reflection statement, use the GOC reflection statement template, or alternatively use a reflection template they have devised themselves or one provided by their professional body or employer.

The GOC guidance on reflection tells practitioners what is involved in order to comply with the CPD scheme requirements and a glance at their statement template will give registrants a good idea of what is involved.1

Registrants need to describe the CPD they have completed, its format and whether they completed the CPD on their own or as part of a group. They should also state their reasons for completing it and link the CPD to the learning outcomes in their personal development plan. Registrants should reflect on the knowledge, skills or insights gained and whether or not they achieved the anticipated learning outcomes. If so, how? If not, why not?

There should also be reflection on how the CPD will impact professional practice, whether it will change as a result, and any benefits it will bring for the practitioner, patients, peers, practice, or organisation. Reflection often highlights further learning or development needs and, if so, registrants must state how these will be addressed.

Before we look further at the specifics of the GOC CPD scheme, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that reflection is something we all do often and, actually, we are pretty good at it. Reflection should be used daily, not simply as a chore related to CPD. It is therefore useful to have a formal understanding of some models of reflection in order to choose one that is best suited to one’s needs generally or to specific situations in particular. Where possible, case studies will be used to illustrate reflection as it has been applied in practice.

Background

John Dewey introduced the concept of reflective practice in 1933, describing it as ‘active, persistent and careful consideration… of knowledge’ that can help an individual explore their experiences to develop critical thinking and learning skills leading to new understandings and appreciations.2

Half a century later, in the 1980s, social scientist Donald Schön defined reflective practice as ‘the ability to reflect on one’s actions so as to engage in a process of continuous learning.’3 Around this time, David Kolb introduced the concept of experiential learning, suggesting that individuals make sense of concrete experiences by reflecting on them and, through abstract conceptualisation, can apply theoretical knowledge to inform further action and new experiences.4

Other popular models of reflection in healthcare practice include the framework for reflective practice from Rolfe et al,5 Honey and Mumford’s learning cycle,6, 7 and Gibbs’ reflective cycle.8 Burch’s four stages of learning, sometimes known as the learning curve, can also be usefully applied.9

Schön’s Model; Reflection Before, During and After Action

Many practitioners follow a pared down version of Schön’s model,3 one which differentiates between reflection during action and reflection after action; an in/on approach. Practitioners describe how they reflected while in action; how they were able to ‘think on their feet’ in the moment and adapt their approach to changing circumstances, such as a patient becoming agitated or revealing something in their history that changed the practitioner’s approach. They then reflect on their action, thinking retrospectively about what went well, what went less well, and what might be done differently if they had that time again.

School children are familiar with this model as a common way teachers give them feedback on their homework.

Schön’s model,3 when considered more fully, is concerned with reflection before, during and after action and, although prior reflection is often not carried out either in practice or in relation to CPD, it is of vital importance to patients if they are to have optimal outcomes. Rather than planning and preparing in advance to see a patient, all too often practitioners are reactive to the demands placed upon them. However, a little reflection in advance of seeing the patient maximises the chance of getting things right first time. For both optometrists and dispensing opticians, investing a few minutes at the beginning of the clinic reviewing previous records is time well spent. Nothing frustrates patients more than having to retell a story that is already well documented in previous records, especially if their story includes a history of error or complaint.

Case study

The dispensing optician took a call from Ms B to book a sight test. She related that she had been discharged from the hospital. She had been under the care of the ophthalmologist for strabismus surgery (due to Brown’s syndrome) and, subsequently, the orthoptist because the surgery had not been successful.

She wished to have glasses with ‘proper prisms’ instead of the stick-on Fresnel prisms she had been prescribed as they impeded her visual acuity. After booking the appointment, the optician reflected that the patient was well informed and likely to be very demanding and, also, that he did not know the first thing about Brown’s syndrome or what the patient was likely to require. He also reflected that the newly qualified optometrist Ms B was booked in with may also not be adequately informed and so resolved to identify online resources that might help improve the care of the patient. He informed the optometrist that they, perhaps, had some homework to do in advance of the patient attending. The optometrist was very grateful for the ‘heads up’ and, afterwards, felt it had made a big difference to how they were both able to adapt their approach successfully during the patient visit. The case was later used as a registrant-led peer discussion, completing the cycle of learning for the wider team of registrants in the practice.

The Four Stages of Learning

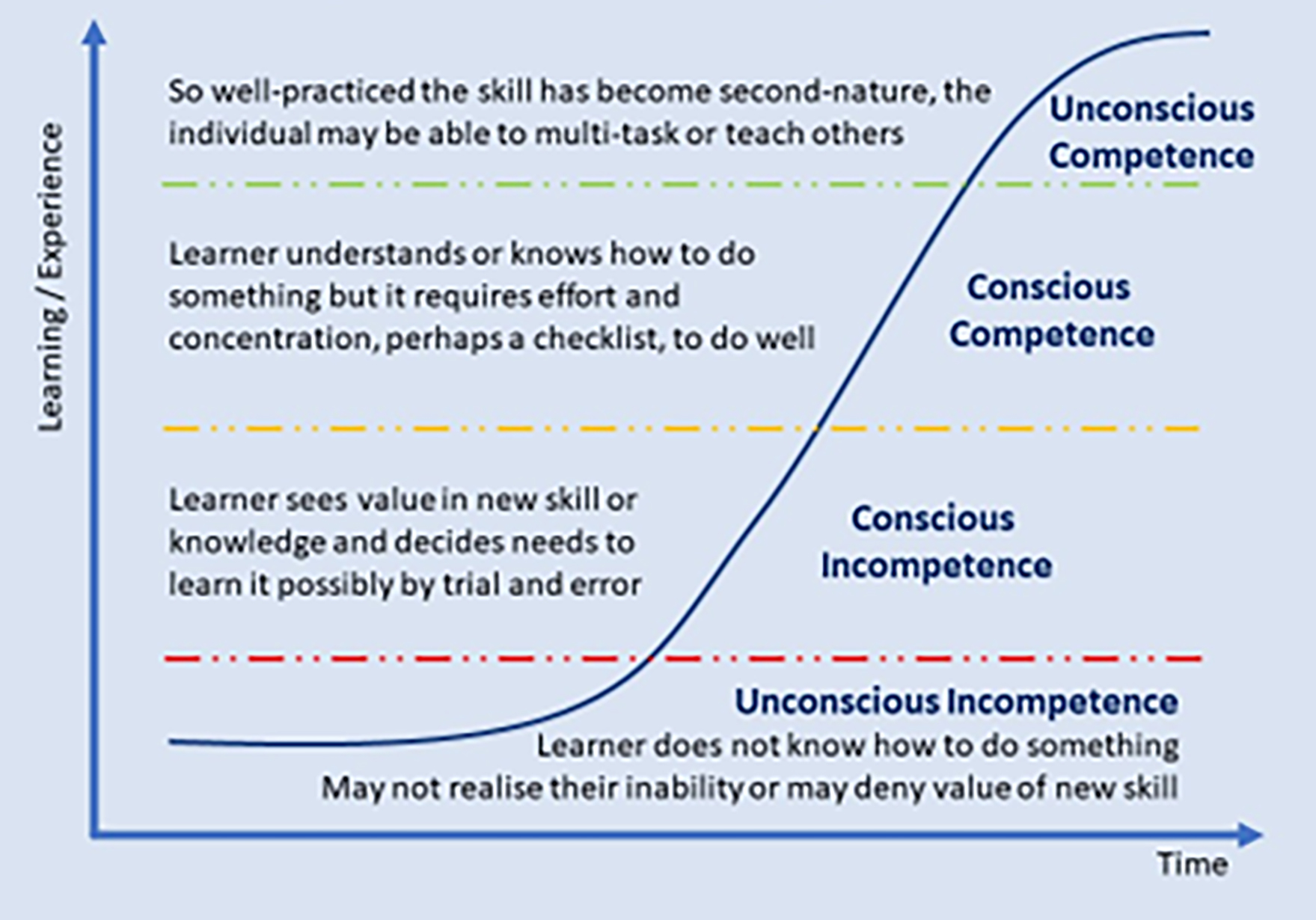

The case study above illustrates an important concept in healthcare practice; that of conscious incompetence. This is outlined as the second of the four stages of learning (figure 1) as first proposed by Burch.9

The four stages are:

- Unconscious incompetence; the individual does not understand or know how to do something and does not necessarily recognise the deficit. They may deny the usefulness of the skill. The individual must recognise their own incompetence, and the value of the new skill, before moving on to the next stage.

- Conscious incompetence; though the individual does not understand or know how to do something, they recognise the deficit, as well as the value of a new skill in addressing the deficit.

- Conscious competence; the individual understands or knows how to do something. However, demonstrating the skill or knowledge requires concentration.

- Unconscious competence; the individual has had so much practice with a skill that it has become second nature and can be performed easily. As a result, the skill can be performed while executing another task.

Figure 1: The four stages of learning first proposed by Burch.9

Patients continually present with new or unusual situations that a practitioner may never have dealt with before and may be beyond the scope of their knowledge or capability. At this point they are likely to realise that they are unlikely to be able to deal with the patient effectively and must resolve either to seek assistance or to gain the requisite skills themselves.

Case study

A contact lens patient attends a practice with a sore, red eye. The receptionist, of just two months’ experience, is on her own as it is lunchtime. However, being a contact lens wearer herself, she knows that, in this situation, the contact lens optician (CLO) would instil fluorescein. So, she resolves to do this herself and instils the fluorescein. Fortunately, before she is able to teach herself how to use a slit lamp, the CLO returns from lunch and is able to rescue the patient before any harm is done.

Non-qualified assistants who think they know what they are doing, but actually do not, are the cause of a significant number of adverse incidents in eye care practices, especially those with high levels of staff turnover. Staff training is an issue and, on reflection, it is best to have staff that are qualified at some level. The qualification provides an indication of their skill level to existing, new and locum practitioners, each of whom have responsibility for supervising and accountability in law for the actions of support staff.

Practitioners need to be assured that their assistants are competent at the appropriate level and understand what they can, and cannot, do. In the absence of registration for assistants, as currently exists for other professions, mandatory qualifications at levels 2, 3 and 4 (depending on the level of responsibility) are the best way of achieving this.

Rolfe et al What? So what? Now what?

Rolfe et al5 built on the work of Borton10 and recognised that, for reflection to be carried out at all by busy practitioners, it must be easy to do so quickly while memories are still fresh. The framework for reflective practice thus developed asks the simplest of questions:

- What? Briefly describe the episode and any actions, outcomes, problems and feelings.

- So what? Discuss and examine learning and ideas about practice, attitudes, and relationships.

- Now what? How can thinking and ideas be applied to improve future outcomes?

Case study

In a different era, when the GOC served claret with lunch and ABDO examiners could smoke during viva assessments, an optometrist, who was both a GOC council member and a bigwig in the local optical scene, arrived late for work. He was visibly drunk, with his shirt buttoned asymmetrically and his shirt tail protruding from his flies. The newly employed pre-reg dispensing optician helped him to dress himself properly and tied his tie for him, while the dispensing optician manager procured strong coffee and extra strong mints to try and sober him up and mask the smell of brandy.

The first sight test was a disaster, with the elderly patient in tears and her middle-aged son apoplectic at the arrogance of the optometrist who was clearly not used to his behaviour being challenged by anyone.

On reflection, this optometrist should have been sent home, for his own good, the good of the patient, and the reputation of the practice. Commercial pressures had over-ridden common sense as it was very difficult to get optometrist cover in those days. Faced with a patient in tears and her son demanding that something be done, the only sensible option was to contact the day’s remaining patients and rebook them for another day; but then what?

This episode resulted in the practitioner being reported to the GOC, whose subsequent investigations took a dim view that the dispensing optician manager allowed the optometrist to see the patient when clearly unfit to do so. Fortunately for the dispensing optician, but very unfortunately for the optometrist, the case never came to fruition as the practitioner died suddenly of a massive heart attack; glass in hand, at the bar of his favourite hostelry.

Practitioners are reminded that if they have a drink or drug problem, or may be unfit due to mental or physical health issues, they have a duty to declare this to the regulator with whom they are registered.

Kolb and Honey & Mumford

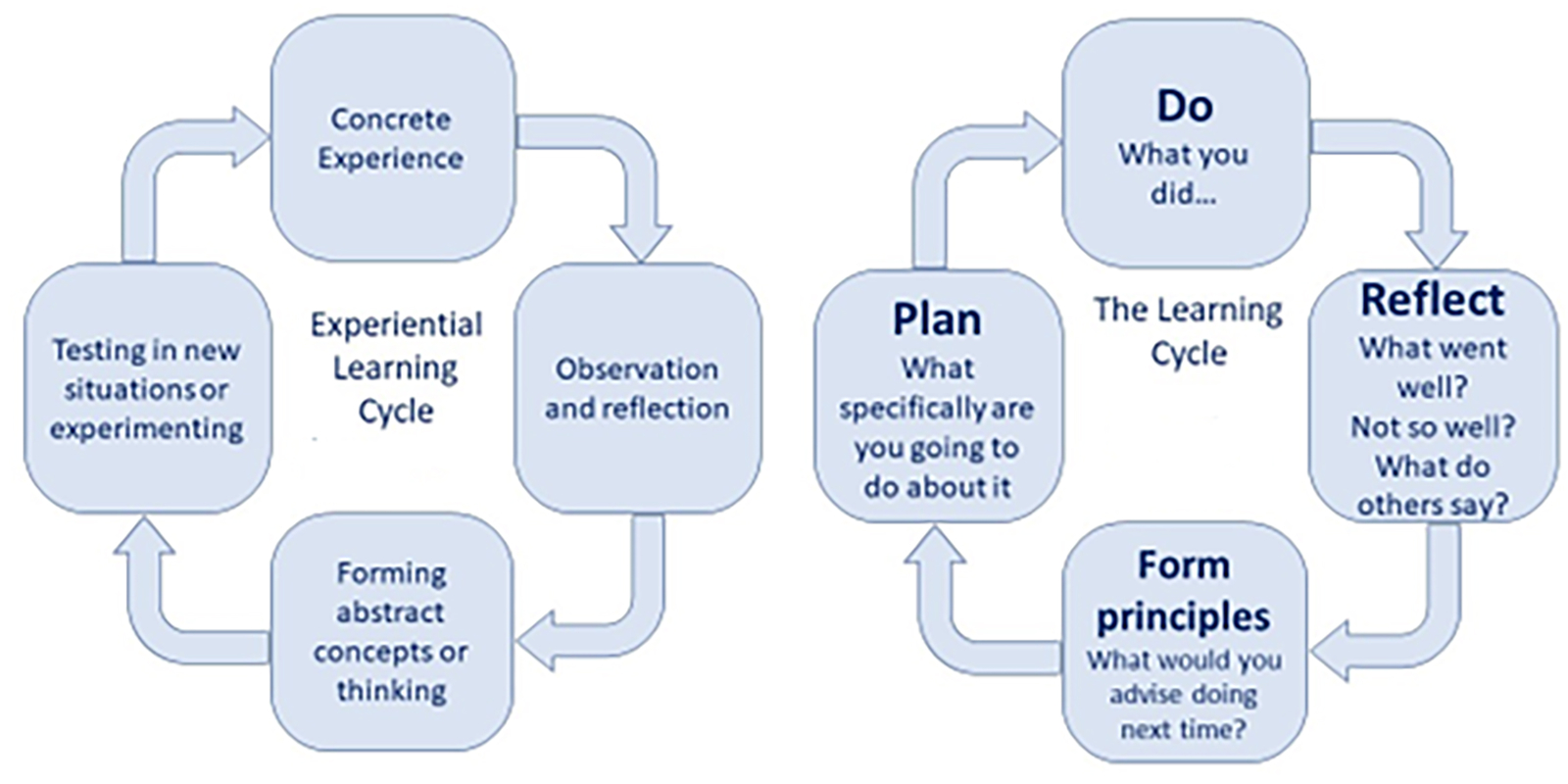

Kolb4 is known for developing the Experiential Learning Cycle (figure 3), which was developed further a couple of years later by Honey & Mumford into the slightly more user-friendly Learning Cycle (figure 4).6, 7

Figure 3 & 4: (left) Korb’s Experiential Learning Cycle,4 and (right) Honey & Mumford’s Learning Cycle6, 7

Both cycles require that following an action or experience an individual reflects on what happened, what went well, what could have gone better, and what the evidence and other people suggest. Then, it is necessary to hypothesise and generate ideas on how the situation might have been improved, and finally to devise a plan and procedures to put those ideas into practice.

Case study

The authors have met a large number of ECPs, at CPD events and elsewhere, who can reflect upon the following familiar situation. However, these comments are from a locum dispensing optician.

‘My first day of locum work at this practice, I was allocated to be “on concerns”. I wasn’t familiar with this term, but soon discovered it was a dedicated clinic, with appointments scheduled every 10 minutes, to address the concerns of patients who weren’t happy with their new spectacles and for whom any adjustments attempted by optical assistants hadn’t solved their problem.

‘Reflecting on the 30 or so patients I saw that day, around a third had their vision and/or comfort restored following frame adjustments and realignment. However, two thirds were beyond adjustment and had experienced problems due to a range of fundamental errors, which included:

- Refraction error

- Rx data entry error

- Inappropriate frame selection

- Measurement error

- Manufacturing error

‘After a few more days working there, I discovered that the practice “remake rate” (the percentage of new spectacles that require to be made again or refunded) was running at over 20% so far this year, and the year was already half gone.

‘I reflected that this was a ridiculous situation. An over-riding principle in eye care practice, or in any business for that matter, is GIRFT; Getting It Right First Time. I approached the franchise partners with a view to them employing me to carry out training for support staff and CET for registrants, with a target of getting the cumulative target down to 12% by the end of the year, and to 4% ongoing. We ran peer review for the optometrists, selecting actual case records where the patient had too much minus or had an inappropriate reading addition for their working distance or other refraction error, and also where they had signed off as supervisors on poor quality dispensing. The practice also brought in people to train support staff and invested in recruiting new dispensing opticians and providing the opportunity for several optical assistants to train as dispensing opticians. Finally, a new focimeter was purchased and the checking of all jobs, not just those relating to restricted patients, was introduced to hold the lab to account, as it was clearly either not checking its own work or it was allowing spectacles outside of tolerance to be supplied intentionally. The savings made more than covered the costs of these actions.’

A similar issue of spectacles that are not fit-for-purpose are routinely reported throughout the sector and could easily be solved with a little reflective practice and a concerted effort to improve. There seems to be an attitude, when gross margins are so high, that it does not matter if one in five spectacles need to be remade. However, the biggest costs are not related to the products themselves, but to the staff time wasted, the opportunity cost of lost appointments, and the reputational damage incurred.

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

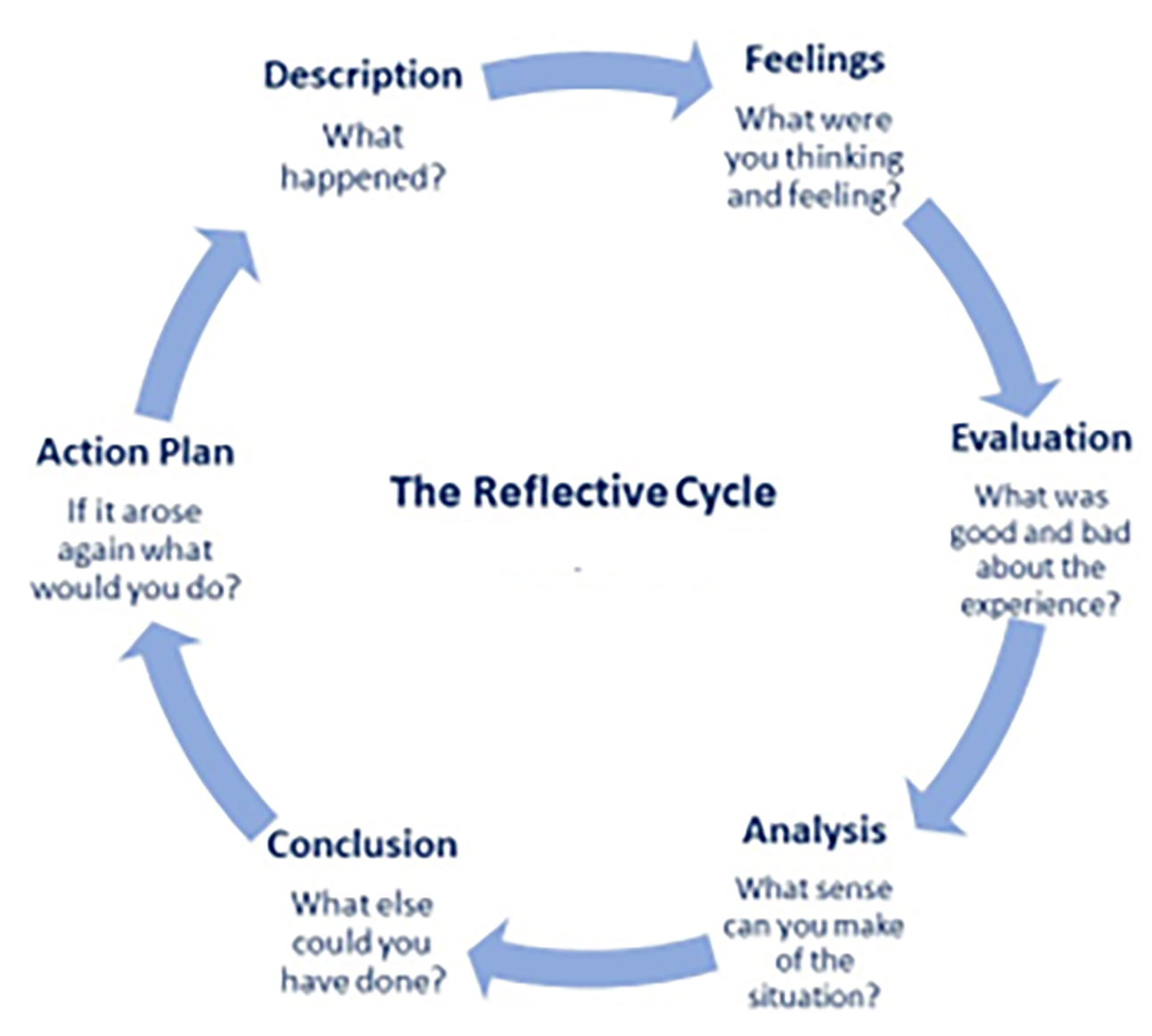

Moving beyond learning cycles, Gibbs adapted these models (figure 5) to recognise that feelings and emotions play an important part in learning, stating: ‘It is from the feelings and thought emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated. And it is generalisations or concepts that allow new situations to be tackled effectively.’8

Figure 5:

Case study

Models with multiple stages are particularly useful for larger pieces of reflective work such as the reflective exercise the GOC requires of registrants towards the end of each CPD cycle and Gibbs’ model is especially aimed at exploring feelings and emotions, as with this reported case.

‘How I feel following completion of my mandatory adult safeguarding training is angry. I’m angry because my employer just assumed I’d be able to get this CET through DOCET and was unaware of the inequity in DOCET funding not being open to dispensing opticians, yet we are still being required to carry out adult safeguarding training as contractors and clinicians taking part in GOS services.

‘I’m also angry because it seems to me that the GOC could do more to undertake some of this CPD itself as it seems derelict in its duties to protect vulnerable adults. Material and financial abuse, and to a much lesser extent, physical, emotional and sexual abuse, are a very real threat to members of the public who avail themselves of optical services in their own home. This risk is exacerbated many-fold when non-registrants provide services alone as happens routinely with domiciliary companies who send unregistered optical assistants to deliver spectacles unaccompanied.

‘I have reflected as a result of this training that vulnerable adults should be added to the restricted categories of ophthalmic dispensing. It is worth remembering that in the same way that paedophiles have been shown to be attracted to roles that enable them to be alone with children, people who want to abuse vulnerable adults will be attracted to roles where they can have time alone with them.

‘Currently, there is no protection from unregistered people who intend to groom such patients for future financial gain, amendment of their last will and testament and so on.

‘An elderly relative, who came to us for Christmas dinner for about 12 years after her husband died, left her ‘optician’ thousands of pounds and didn’t leave me a penny when she died some years ago. And another elderly relative, who is registered blind, has been conned out of thousands of pounds by so-called carers.

‘Harold Shipman, acting alone, not only murdered hundreds of people, but his prime motivation, initially at least, seems to have been financial.11 Registration and a DBS check should be compulsory for all providing ongoing care of vulnerable adults in their home environment. I also reflect that all patients who require home care and/or a GOS3 voucher for spectacles are vulnerable in some way, if only financially, according to this safeguarding training. The GOC does not seem worried about mere transactions or money, otherwise things dealt with by the Optical Consumer Complaints Service (OCCS) would result in fitness to practice proceedings against dispensing opticians and optometrists who supervise unqualified dispensers more often.

‘People who have been subject to material or financial abuse seem to be of the view that bruises heal but once someone has been deprived of their lifesavings or some other significant sum the psychological harm never goes away partly because the money cannot be regained and also because the abuse has taken place in their home and is relived every time they want or need something they can no longer afford to buy.’

Sometimes, when a practitioner is angry or upset, reflection may be better recorded as an ‘unsent letter’ that helps registrants to clear their heads of the immediate emotions that accompany distressing incidents. Later, the stages of evaluation and analysis can be conducted in order to draw more objective conclusions and plans.

Practitioners reflecting things that could have been done differently to produce a better outcome do not necessarily know how to take a different approach, so an important part of reflective practice is identifying areas where knowledge and understanding needs to be improved. Lifelong learning is a key aim of reflective practice, enabling practitioners to keep up to date.8

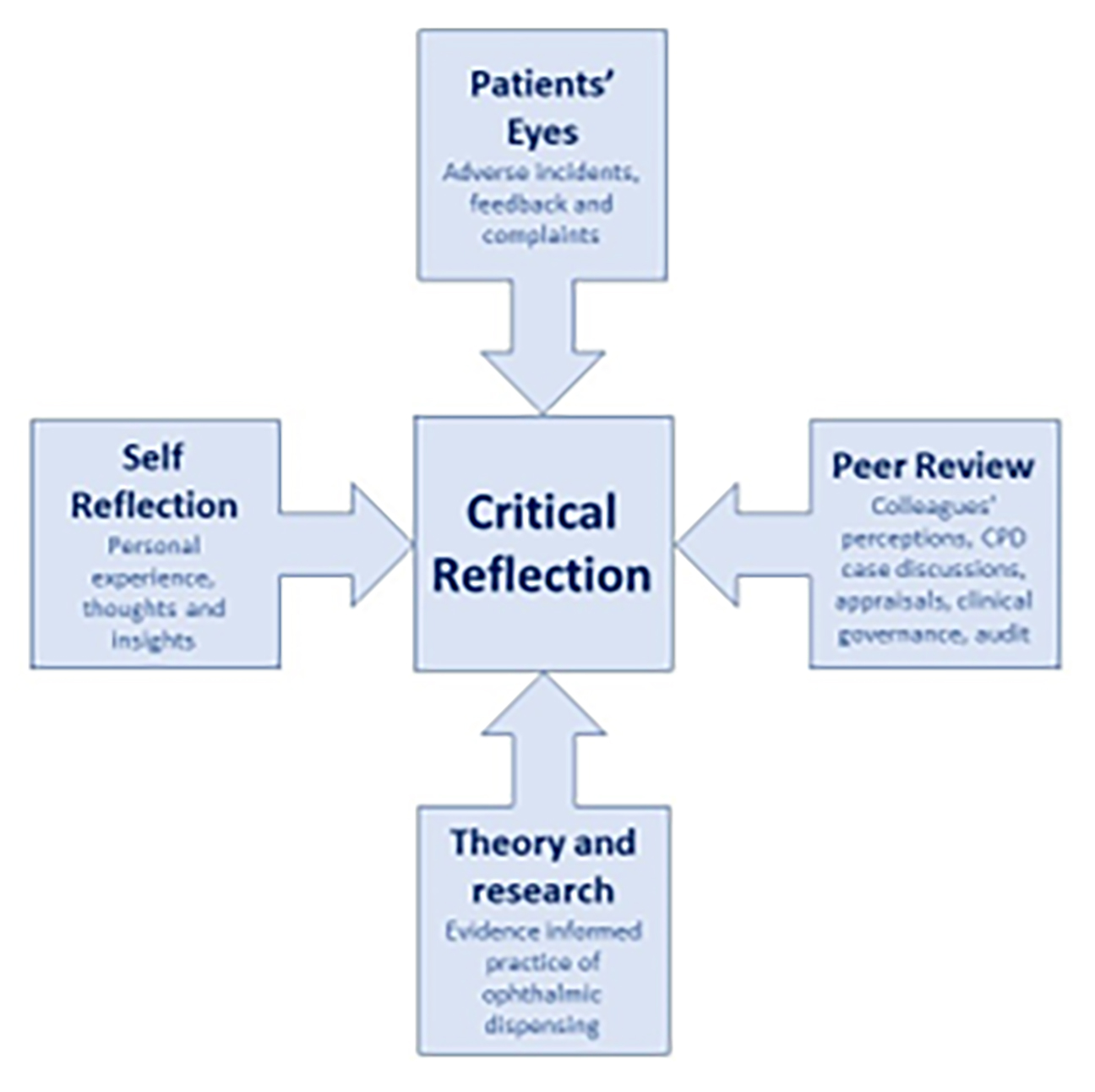

Four Mirrors of Critical Reflection

In higher education, a common model of critical reflection used by teaching practitioners is Brookfield’s Four Lenses of Reflection.12 Many aspects of Brookfield’s model are specific to teaching, and ECPs may quibble anyway that lenses refract and not reflect. So, these authors have borrowed and adapted the model to create the four mirrors of critical reflection (figure 6) to make the point that, whatever model of reflection is preferred, it is important to take into account these four different perspectives.

Figure 6:

It is worth pausing here to consider what we mean by the word ‘critical’ when we talk about critical reflection or critical thinking skills. In everyday life, critical can mean finding fault and lead to negative comments, or it can mean crucial, key, decisive or important, as in a ‘critical moment’, ‘critically ill’ or a ‘critical decision.’

Critical thinking is a key transferable skill that should result from all higher education and, within the context of pre-registration studies and post-registration reflective practice, ‘critical’ takes on a different meaning. Critical thinking refers to the processes of exploring possibilities and weighing up alternatives before making a rational decision what action to take. It requires a healthy dose of scepticism and the ability to imagine and explore alternatives, identify and challenge assumptions, and recognise the importance of context.

While it is perfectly possible to produce meaningful improvements in professional practice through critical thinking and self-dialogue, self-reflection is clearly limited in what it can achieve, especially for those who are newly qualified or at the early stages of their career and have fewer experiences to draw upon.

All ECPs can benefit from the experience of their peers, including colleagues, employers and fellow delegates at CPD events. It is also useful to gain the views of other healthcare practitioners involved in the care of patients. The authors have, over the years, enjoyed interprofessional CPD with pharmacists, doctors (including general practice, emergency medicine, diabetes care and ophthalmology), physician associates, ophthalmic nurses, orthoptists and sight loss support workers, including rehabilitation officers for the visually impaired (ROVIs) and eye clinic liaison officers (ECLOs).

The GOC requires its registrants to put the patient at the heart of all their decisions and the power of the patient voice in reflective practice cannot be underestimated. It is important to reflect on patient feedback, especially that given in relation to complaints or adverse clinical incidents. The authors have for some time been involved in the award-winning CPD programme Seeing Beyond the Eyes, which aims to introduce registrants to visual impairment from the patient perspective and discuss practical aspects of saving sight and supporting sight loss. The sessions are brought to life by the inclusion of visually impaired patients and support workers within both the presentation team and the discussion groups. It is clear these alternative perspectives force registrants to reflect more deeply.

The final mirror of reflection is the knowledge, theory, and research evidence that underpins and informs eyecare practice (see part 28 of this series, Optician 08.07.22). This is particularly important if prior reflection on a forthcoming episode reveals a lack of knowledge that must be investigated prior to seeing the patient. It is also important, if retrospective reflection reveals a lack of knowledge, that action is taken to address this so that the practitioner is ready to see the same patient again, or similar patients in the future.

Portfolio

A portfolio is a collection of documents that provides evidence of a practitioner’s achievements and professional development. Most healthcare professions, including doctors and nurses, are required to keep a portfolio as evidence of their continuing professional development and employers often review these annually to ensure compliance.

The GOC has stopped short of requiring a portfolio, although its MyGOC CPD system is a form of electronic portfolio in its own right. Regardless, it is a good idea for registrants to maintain a portfolio to facilitate compilation of the reflective exercise towards the end of the CPD cycle and to act as a record of self-directed and provider-led CPD. The GOC has indicated that it will audit up to 10% of CPD activity, and having everything in one place is clearly of benefit should a registrant be subject to this.

Most registrants should be familiar with what a portfolio involves, as they have long been a feature of undergraduate eye care education. Historically, ophthalmic dispensing portfolios have included learning outcomes relating to record keeping, demonstration of technical knowledge and justification of lens and frame choices, and have not been particularly reflective in nature. Since the outcome of the GOC’s education strategic review was completed in 2022, reflection will rightly take a much more prominent role in summative assessments prior to registration.

Reflective Journal

An alternative to a portfolio, or a constituent part of one, is a reflective journal. This is simply a notebook, diary or folder in which registrants record interesting or challenging patient episodes, adverse incidents, interactions with colleagues and so on, and reflect upon these using one of the models or a blend of frameworks that best suit their needs.

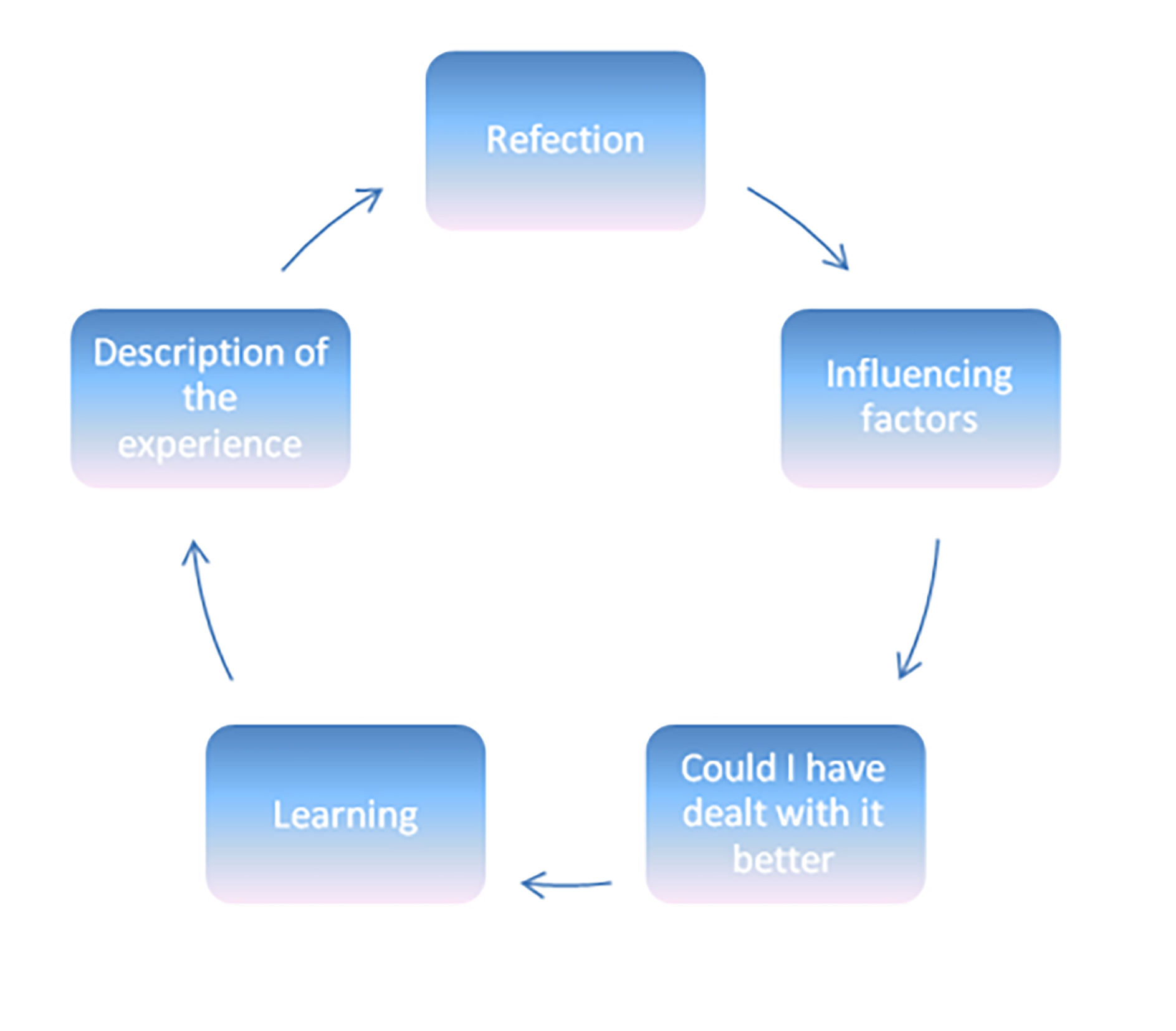

Johns’ model of structured reflection13 (figure 7), which was later updated by Rolfe et al,4 is highly suited to be used by both student practitioners and those involved in their supervision as it is designed to adopt a diary structure, asking a core question: ‘What information do I need to access in order to learn through this experience?’ Practitioners are encouraged to describe their experience including any causes, background and context.

Figure 7: Johns’ model of structured reflection13

When reflecting, practitioners should ask the following:

- What was I trying to achieve?

- Why did I intervene as I did?

- What were the consequences of my actions for each of the following?

- Myself?

- The patient and their family

- The people I work with?

- How did I feel about the experience when it was happening?

- How did the patient feel about it?

- How do I know how the patient felt about it?

Practitioners should also think about what internal and external factors and sources of knowledge influenced, or should have influenced their decision making. They should then ask themselves whether they could have dealt with the situation any better in the light of the choices they had at the time and the consequences of those choices. Finally, a structured reflection following Johns’ model should include recognition of the learning that has taken place in the light of past experience and future practice, and any changes to knowledge.

Substantial reflection, providing it involves some additional research, can also be recorded as self-directed CPD.

Case study

‘Mr A, an ex-pat Saudi oil worker, attended every six months or so to purchase new spectacles and sunglasses. We would normally debate how his coatings had broken down, how the practice offered a 12-month warranty, and how this didn’t apply because he left his glasses on the dashboard of the car in 50ºC heat and had been recommended not to have an AR coat at all. A 20% discount would be provided, and Mr A would spend another £1,000.

‘On this occasion when Mr A came to collect his glasses, I noticed a nasty looking multi-coloured lesion, about 10mm across, on the side of his head behind his left ear. I reflected that Mr A was entirely unsuited to working in sunny climes, being of pale complexion (now deeply freckled and with many moles), with ginger hair and now substantially bald. I was pretty sure that I was looking at some form of skin cancer.

‘I had already determined that Mr A was heading back to Saudi Arabia in a few days’ time, however, I felt that although not an emergency it was a matter of urgency that a medical opinion be sought. As it happened, we both attended the same surgery, and I knew that Dr S was also a specialist in dermatology who also did minor surgical procedures such as mole removal. I told Mr A, in the presence of Mrs A, that he should call in the surgery on his way home and ensure that Dr S had a look at it before he went back to Saudi Arabia.

‘On the same day, Mrs A ordered her new glasses, choosing from the selection of high end Silhouette frames we had got in on approval for her to try, and a couple of weeks later I telephoned to advise her that they were ready. I took the opportunity to ask how Mr A had got on at the doctors and was informed that he hadn’t bothered going and was going to get it looked at by the medic at work back in Saudi. This left me in a dilemma; should I tell her I thought he had skin cancer and worry her, perhaps unnecessarily? When Mrs A collected her glasses later that day, I had by then spoken with a colleague and had looked at the eyelid lesions section in the practice copy of Kanski. As a result, I decided that I should tell her of my suspicions and that she must ensure that Mr A was seen by a doctor out in Saudi.

‘The next I heard was a few months later, when Mrs A called to thank me for identifying the skin cancer, which turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma, and to express the hope that it could be treated. It later transpired that it had already metastasised and spread to other parts of the body. Mr A would be dead within six months of his diagnosis, just a few months before he was due to retire.

‘This case happened a long time ago and I have often reflected on it. Most recently, in the light of the tragic Vincent Barker case, GOC v Rose. This concerned the death of a child from a build-up of fluid on the brain, later confirmed to be acute on chronic hydrocephalus secondary to gliotic obstruction of the rostral part of the fourth ventricle. The case resulted in the involved optometrist being subjected to a decade of fitness to practice proceedings, including being convicted in 2017 of gross negligence manslaughter, which was subsequently overturned on appeal.14

‘Was I guilty of gross negligence manslaughter?

‘Although I had made a note of my advice on the record card at all stages I had failed to send a formal referral letter to the doctor because it would not have got there in time given that Mr A was travelling abroad within a few days and was going to be there for four or five months. At that time, in the same way GPs today just tell patients to get their eyes tested and do not complete any form of formal referral, it was common to simply give verbal instructions and expect the patient to act upon them. Unfortunately, in this case Mr A did not act on my advice and, even if he had, it is unlikely it would have made a difference, nevertheless I was troubled by how I could have persuaded him to do as advised.

‘It is not often, as a dispensing optician, I have to refer patients for medical treatment as I usually pass this on to optometrist colleagues. However, I resolved as a result of this and previous reflections, including a peer discussion of the case, to always do so formally using the ABDO recommended referral form or local protocol and to always give the patient a copy in an unsealed envelope so that they can read it and check online what it means if they wish before consulting the intended medical practitioner. This is in addition to always sending a copy to the medical practitioner.

‘I also feel that patients should always be told the truth and, if there is a level of uncertainty, be informed of this. I would use words along the lines of: “Mr A, I have found a nasty looking skin lesion behind your ear and I need you to get it looked at urgently. I don’t know for sure what it is, but I suspect it is a form of skin cancer. I know Dr S at your surgery specialises in dermatology and also has a clinic at the hospital, so he is probably the best person to see. I know you are going back to Saudi in a few days, would it be OK if I called the surgery for you now and arranged an urgent appointment?”

‘Nowadays, we all have a camera in our pockets and easy means of adding photographs to referral letters so, if this happened again, I would also be sure to include a photograph of the lesion so that its growth could be tracked more easily.’

The reflection about Mr A goes on and on; this is only a short extract. Although it does not answer Johns’ Model questions specifically, it largely covers all aspects. In terms of the feelings of family, this case transpired to resurface time and again over the next few years as it turned out Mr A’s death in service benefit applied only to accidental death, not cancer, and his pension died with him, leaving his widow and his mother, who lived with them in a large, detached house, surviving on state pensions and nothing else. The dispensing optician was able to persuade Mrs A they could avail themselves of state benefits that then entitled them to GOS3 vouchers, so they could at least reglaze their frames at little cost.

Reflective Exercise

It is hoped that ECPs now have a flavour of what reflective practice involves. It might now be useful to conclude with some guidance relating to the reflective exercise that GOC registrants are required to carry out and document, based on the content of their personal development plan, by the end of the CPD cycle. This will involve discussion with a peer, who may be another registered healthcare professional, including an optometrist or dispensing optician, but cannot be a close friend, employee or someone related to the ECP.

What is reflective practice?

The GOC defines reflective practice as the process where you think about your experiences to gain insights about your practice and to improve the way you work or the care you give to your patients. Reflection is part of the continuous learning and development expected of you as a professional throughout your career.

What are the benefits of reflective practice?

Reflection supports you in your professional development and practice. It helps to embed good practice and has been linked to improvements in the quality of care given to patients.

When should I carry out the reflective exercise?

The GOC advises you to carry out the reflective exercise when you have met all or most of your CPD requirements. They recommend undertaking your reflective exercise with your peer towards the end of the cycle, so that you can have a more meaningful discussion about progress against your personal development plan.

What should the reflective exercise consist of?

The reflective exercise must involve a discussion with a peer. The purpose of the exercise is to discuss and document reflections on your progress against your personal development plan and CPD requirements, and reflections about your professional practice more generally over the course of a cycle. The discussion must be documented by you and recorded as having been completed on MyCPD. You can use the GOC’s template to directly document your discussion, alternatively you may upload your own template, perhaps based on one of the models above, or one provided by your employer, contracting organisation or professional body.

You should reflect on:

- Your CPD plan

- Your CPD activity

- Any reflection statements already carried out to date

You should also be thinking about what other CPD activities you need to carry out for the remainder of the cycle (if any), and any other information you have collected about your professional practice. For example, do you have any feedback from your line manager or employer, patient satisfaction data, or results from a clinical audit if available.

Can I have the discussion remotely?

Yes, you can undertake the discussion either in person, via video call or telephone.

How will the GOC know I have completed the exercise?

You will be asked to self-declare that you have completed the reflective exercise. Your peer must provide evidence to confirm that they have undertaken the exercise with you. The GOC will randomly review a selection of written reflections to ensure compliance.

How will this exercise help me to plan my CPD for the next cycle?

You can use your reflective exercise to think about what you might want to do in the next CPD cycle. If you are using the GOC’s template on MyCPD, the written reflection will be displayed to you at the start of the next cycle to assist you in setting new goals.

What if my plans change and I have undertaken different CPD to that set out in my personal development plan?

This is absolutely fine, as long as you meet the minimum CPD requirements and set out clearly in your reflective exercise why you have undertaken learning in different areas than you originally planned.

Conclusion

By asking ECPs to reflect on their CPD, the GOC is at risk of reducing their effectiveness as reflective practitioners. Reflective practice should always be about real patient episodes or elements of professional practice, such as policies and procedures, that impact upon patient care and not simply about continuing professional development activities, such as training courses, important though they are.

By using the models and frameworks proposed by Schön, Gibbs and others described in this article, in the light of the four mirrors of critical reflection, and by keeping a reflective journal as part of a wider reflective portfolio, ECPs will find it easier to keep up to date. Registrants will be able to reflect on their actions, so as to engage in a process of continuous learning in order to improve their practice to the benefit of patients.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO AFHEA is Course Lead for BSc (Hons) Ophthalmic Dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, board member and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians.

- Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CPD provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College.

References

- General Optical Council. Reflection statement, reflective exercise. https://cpd.optical.org/registrant/reflect [Accessed 21 July 2022.]

- Dewey, J. Experience & Education - the Kappa Delta Pi Lecture Series, 1938. New York Free Press Edition (2015), Simon & Schuster, 978-0-684-83828-1.

- Schön, D.A. (1992). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

- Rolfe G. et al. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1986) The Manual of Learning Styles, Peter Honey Associates

- Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1986) Learning Styles Questionnaire, Peter Honey Publications Ltd

- Gibbs G (1988). Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford

- Burch, N. (1970). The four stages for learning any new skill. Gordon Training International, CA

- Borton, T. (1970) Reach, Touch and Teach. Pp99 -105. London: Hutchinson

- Keith Soothill & David Wilson (2005) Theorising the puzzle that is Harold Shipman, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 16:4, 685-698

- Brookfield SD. (2017) Becoming a critically reflective teacher. 2nd edition. J Wiley Brand, 2017

- Johns C (1995) Framing learning through reflection within Carper’s fundamental ways of knowing in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 22, 2,226-234

- https://www.opticianonline.net/news/suspension-for-optometrist-cleared-of-manslaughter