It is incumbent upon all registered opticians to keep their knowledge and skills up to date in order to comply with the Standards of Practice expected of the professions by the General Optical Council (GOC) in the UK.1 In other jurisdictions where optics is regulated, very similar responsibilities apply such as those laid down by CORU in Ireland.

Dispensing opticians and optometrists must be competent in all aspects of their work, including face-to-face patient interactions (in other words, clinical practice) and any other responsibilities they have relating to their role, such as supervision of student and post-graduate trainee registrants and non-qualified dispensing assistants, management, teaching, and research.

Furthermore, it is also clear that registrants must not perform any roles for which they are not competent. With regards to ophthalmic dispensing, this increasingly poses something of a conundrum as dispensing has become a smaller and smaller part of optometrists’ training, few optometrists in community practice regularly dispense, and even fewer could be said to be truly ‘up to date’ with regards to dispensing. This then poses the question whether many optometrists are competent to supervise ophthalmic dispensing if such supervision is meant to provide for more than just ‘safe episodes’, but also ensure trainees learn the requisite practical and communication skills too, including appraising the latest evidence.

Optical professionals must comply with the requirements of the scheme for Continuing Professional Development (CPD) as part of their lifelong learning commitment to maintaining and developing their knowledge and skills throughout their career as a registrant. This means being aware of current good practice, taking into account relevant developments in clinical research and applying this to the care provided.

Eye care practitioners must also reflect on their practice and seek to improve the quality of their work through activities such as case record reviews, peer discussions, clinical audits, performance appraisals and risk assessments, and by acting on any areas for improvement that are identified.

A key aspect of evidence-based practice is that it ensures practitioners are up to date, and therefore they can properly inform their patients in order to assist them in making decisions relating to their eye care and optical appliances in order to obtain valid consent when interacting with patients. The sale and supply of optical appliances is specifically mentioned in the UK regulations2 as an area of practice where consent is required. Being informed enables eye care professionals (ECPs) to listen to patients and take account of their views, preferences and concerns, and respond honestly and appropriately to their questions.

Before looking at the specifics of evidence informed practice of ophthalmic dispensing, it is worth considering the history of evidence-based practice and its background in medicine.

Before evidence-based medicine

These days, Evidence Informed Practice of Medicine (EIPOM) is a standard module running through all medical school training. However, doctors have not always adopted an evidence-based approach and much advice given was instead based on clinical opinion from unsystematic observations.

A famous example of where clinical opinion has been proved wrong, with disastrous consequences, is the best-selling book Baby and Child Care, by Dr Benjamin Spock, (figure 1), which the authors had a copy of when their children were young. First published in 1945, this book contained erroneous advice to sleep babies on their front to avoid choking if they vomited. This led to the death of an estimated 10,000 babies in the UK and over 50,000 throughout the developed world3 and continued to be printed long after scientific evidence demonstrated that sleeping position was an independent risk factor for Sudden Infant Death (SID).4

Figure 1: Poor advice in Baby and Child Care led to over 50,000 infant deaths

(cover of the book used by the authors when their children were young)

The 1991 ‘Back to Sleep’ campaign in the UK reduced SIDs by a staggering 75%5 and, as a result, the advice in subsequent editions of Spock was changed, but not until over 20 million copies were in circulation worldwide that no doubt continued to be passed on to new mothers for many years.

Aside from this catastrophic advice, these authors can testify that Spock is an excellent common sense manual and, now in its 10th edition last published in 2018, remains a worldwide best seller. Nevertheless, it failed to recognise that babies are helpless to move if they become smothered by bedding, (sleeping bags are a great way to prevent this) whereas babies that are sick while lying on their backs have a very well-developed gag reflex and ability to produce projectile vomit to prevent them from choking.

Patient Questions

It is important, as part of the process of gaining valid consent from the patient for the supply of optical appliances or any other services provided in practice, that registrants, and indeed non-registrants working under their supervision, are able to answer questions honestly and with due regard to the certainty of any knowledge they are imparting, especially with regards to risk. Here is a list of common questions in practice to which the answer is by no means certain, and where it is highly likely the patient will receive a different answer from different practitioners.

- Will wearing glasses make my eyes worse?

- Do vitamins for AMD really work?

- Is myopia management for my child going to be worthwhile?

- Am I right to be worried about having cataract surgery?

- Should I be worried about blue light?

- Which dry eye drop is best for me?

- Which blepharitis product is most effective? Will I get better results if I use more than one?

- What is the maximum time I can wear my contact lenses safely?

- Does it really matter if don’t wash my hands before handling my lenses?

Contrary to popular belief there is a right answer to all these questions. The right answer is to give an honest appraisal of what the research evidence actually says and to stress that we can never guarantee that a particular course of action will definitely produce the desired result in a given individual. We can, however, outline the risks that the research identifies and quantify the odds of success versus adverse outcomes. So, how can we evaluate what evidence actually exists?

Evidence-based practice

Since the 1990s, interest in evidence informed practice of medicine has grown and has been adopted by all healthcare professions under the banner of ‘evidence-based practice’. Optometry was an early adopter of evidence-based practice under the leadership of the College of Optometrists, and contact lens practice has also been research-based for many years with longstanding clinical conferences, such as that of the British Contact Lens Association (BCLA), leading the way. It has to be said that dispensing opticians have been rather late to the party, and Evidence Informed Practice of Ophthalmic Dispensing (EIPOD) has only really been on the agenda since April 2016 when the GOC published new Standards of Practice requiring it.

By comparison to contact lens practice and clinical optometry, a quick search of Google Scholar reveals that there is very little research published in relation to dispensing optics and almost all of it is carried out by optometrists, and even psychologists and public health practitioners, rather than dispensing opticians. This is because most dispensing opticians, including these authors, qualified with a level 6 diploma rather than a bachelor’s degree, which provides institutional access to research databases and prepares students for an evidence-based practice of lifelong learning. At some point in the future, it is likely that, like nursing and many other healthcare professions, dispensing opticians will need to attain an undergraduate degree in order to register.

Indeed, the recent GOC Education Strategic Review6 has elevated the minimum educational level for dispensing opticians from level 5 (foundation degree) to level 6 (bachelor’s degree). Similarly, optometry will be elevated from level 6 to level 7 (master’s degree).

Dispensing opticians who, like these authors, have engaged with further qualifications such as the ABDO ‘top-up’ degree,7 master’s degrees and level 8 qualifications, such as the longstanding Doctor of Ophthalmic Science from Aston University,8 have a head start with getting to grips with evidence-based practice, as reviewing the research literature and critical reviewing is central to all of these courses.

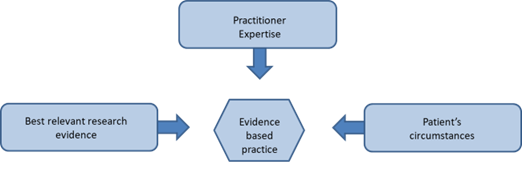

The aim of evidence-based practice (EBP) is to aid clinical decision-making by integrating the best relevant clinical research with practitioner clinical skills and patient preferences, values and expectations.9

As shown in figure 2, it is a process, not just about research evidence but how each practitioner interprets and incorporates evidence from many sources using experience and professional judgement. It is often referred to as clinical reasoning, and places the patient at the centre of all decisions, finding the best option for every person.10 An essential aspect is that EBP provides opportunities to update delivery of patient care and improve patient outcomes.

Figure 2: Evidence-based practice

Looking for evidence

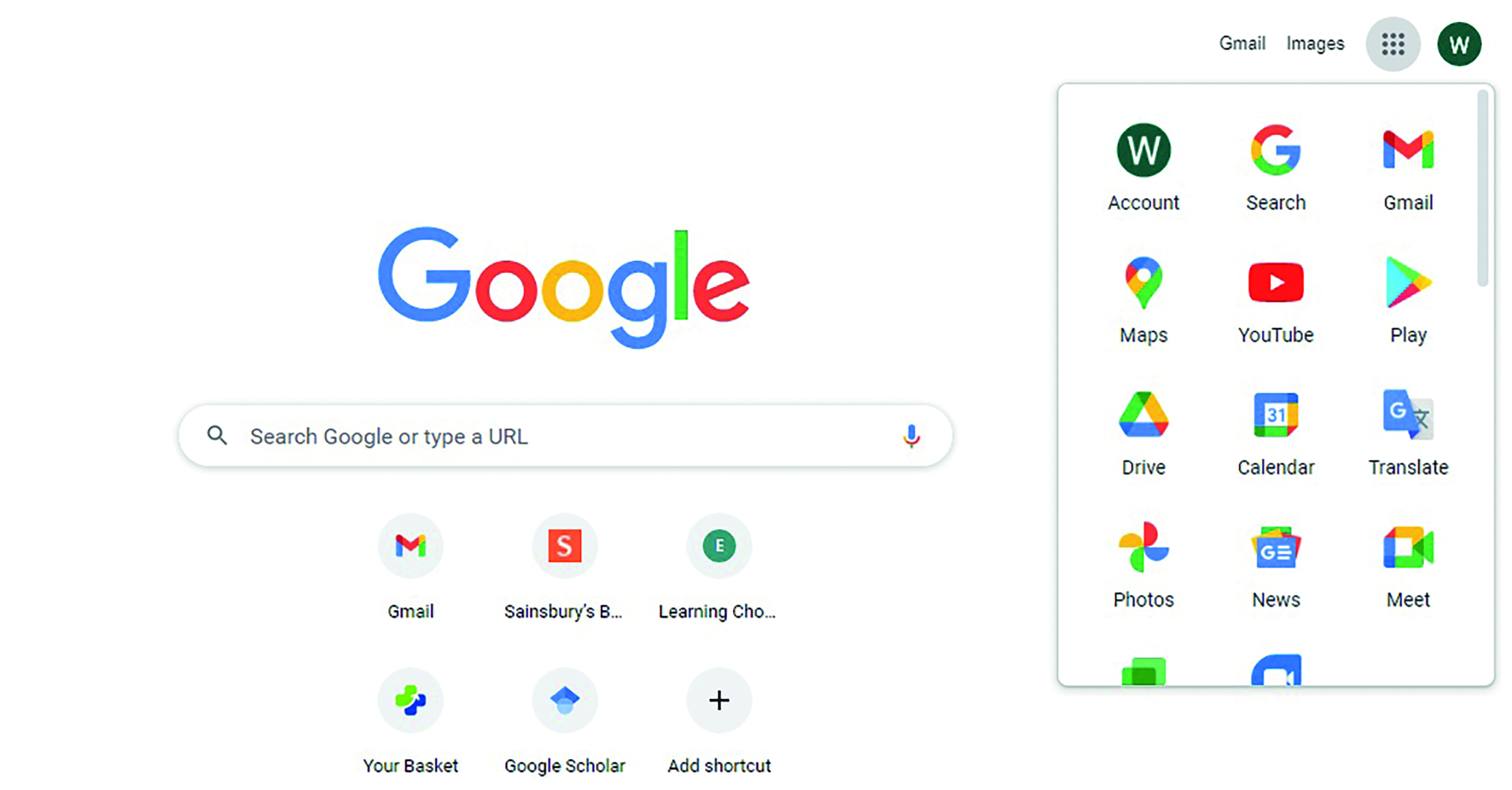

The first thing most of us do when we want to know something is to 'Google it', but is Google an appropriate search engine for academic evidence? The short answer to that is probably not. However, it is often a good starting point and can yield good results if terms are chosen carefully. Google also applies machine learning to monitor your viewing habits so, whereas before the authors embarked upon this series of CPD articles searches would often yield thousands of commercial websites of retailers and manufacturers related to ophthalmic dispensing, today’s searches, even on the standard Google platform, yield increasingly academic results.

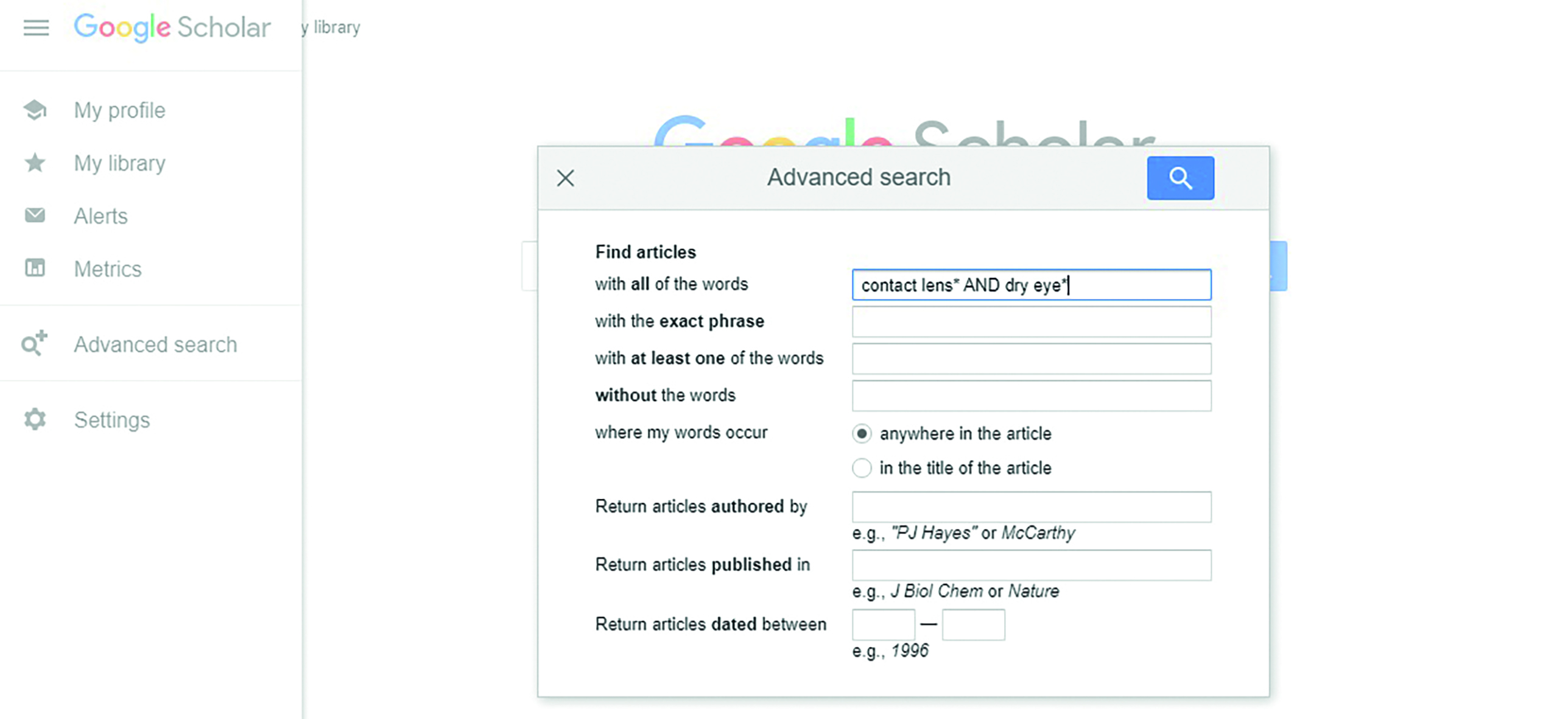

For identifying academic research, a better option is Google Scholar, which can be found within the ‘more from Google’ menu within the Google Apps menu indicated by the nine dots icon towards the top right of the screen in figure 3, although it is probably quicker to simply Google ‘Google Scholar’ and then save to favourites or add a shortcut to the opening screen as shown. Practitioners embarking on further courses of study, whether through a university, the NHS or the College of Optometrists, will also have access to formal academic databases such as OpenAthens, which are often revealed as sources in Google Scholar searches. Unfortunately, to use these databases you require an account or, to pay what will seem to many an exorbitant fee to purchase a paper.

Figure 3: Google Scholar is a great starting point for academic research if you do not have access to an academic database system. Scholar can usually be found in the list of services shown when clicking the nine dots at the top right of Google. Alternatively, it can be added as a permanent shortcut using the URL https://scholar.google.com

Thankfully, much academic research these days is designated Open Access, either from the date of publication or within a period of a year or two, and there is considerable movement towards open access for both patients and practitioners alike so everyone can be informed without bearing undue cost.

The following databases are subscription free:

- Cochrane Library; up to date systematic reviews of healthcare research (analysis of a collection of studies combined)

- Pubmed, Pubmed Central (PMC); full text archive, reviewed and selected by the US National Library of Medicine

- Trip; Medical database basic version. Trip Pro, for which a subscription is required, has greater functionality and greater access to full texts

- Science Direct; free to access but not all journals open access

Search strategy

Whatever database or search engine you are using, you will need to have a strategy for your search in order to find what you are interested in. You will need to think of key words and any possible synonyms, for example:

- Age related macular degeneration, age-related macular degeneration, ARMD, AMD

- Optical centres, optical centration, OCs, OC

- Progressive Power Lens, PPL, Progressive Addition Lens, PAL, Varifocal

It is best to keep it simple to start with, and then vary the approach to either expand or narrow your search depending on the results you have obtained. It is also worth keeping a search diary, especially when conducting research for an academic assignment or an important work project, so that time is not wasted repeating the same searches.

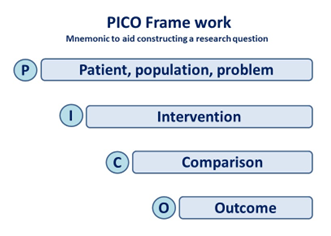

A useful tool for asking focused clinical questions is PICO (figure 4), which helps the practitioner or student to frame their research question or search based on the patient, population or problem that is presenting, the proposed or actual intervention, comparison to other possible interventions (including doing nothing or a placebo), and the possible outcomes which may be favourable or otherwise and can often be quantified in terms of risk.

Figure 4: PICO, a useful tool for asking focused clinical questions

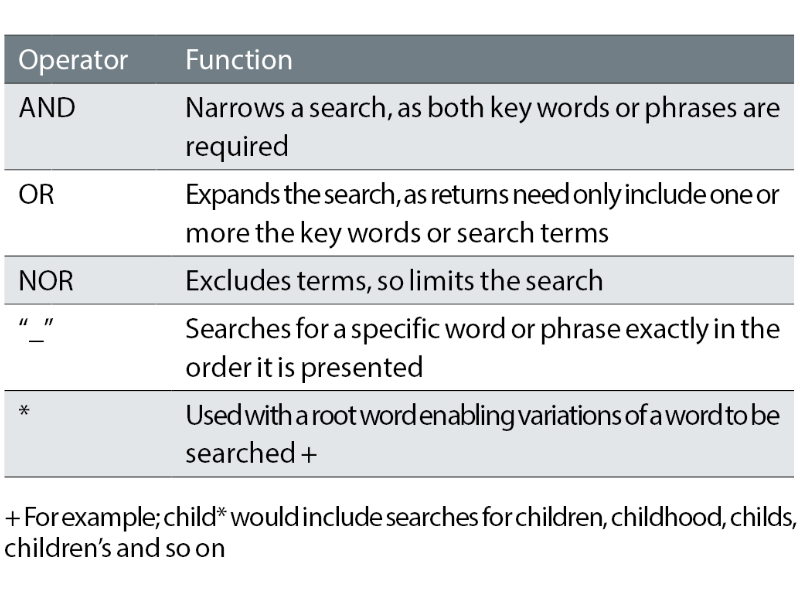

The use of search engines and databases are made very much easier by the use of Boolean operators, based on Boolean logic named after the English mathematician George Boole (1815-64).

The operators are essentially words or symbols that are used to combine search terms to enable a more specific search strategy. A few examples are outlined in table 1.

Table 1: Examples of Boolean operators that might be used in a search of data

This is easiest to understand if you try it for yourself. For example, say you are interested in the effects of contact lenses on dry eye, or the effects of dry eye on contact lens wear. A simple Google search in June 2022 of contact lenses dry eyes yielded nearly 34 million results, with almost all results on the first few dozen pages being commercial organisations. A search of contact lenses OR dry eyes expands the search to 733 million results, whereas contact lenses AND dry eyes narrows things down to 27 million results but still at a level that is far too great to be useful.

Moving to Google Scholar the same search term narrows the results down to ‘only’ 82,800. However, it is immediately obvious that the results on the first page are likely to be of some use rather than just adverts for online contact lens sales.

Using the advanced search function in Google Scholar facilitates a more targeted approach. In figure 5, the * expands the search to include ‘lens or lenses’ and ‘eye or eyes’, but then the search is narrowed by including a date range. This searched yielded 51,800 results and many of the results on the first page will give the researcher ideas for words to exclude in order to narrow the search further. For example, placing the search term in “speech marks” yields a very usable 136 results and has been made more usable by the inclusion of the * after lens and eye as this then shows terms such as ‘Contact lens wear and dry eye: beyond the known’ and ‘contact lens wear, and dry eye signs and symptoms in healthy young females’, etc.

Figure 5: Advanced search in Google Scholar enables much more targeted results

Hierarchy of evidence

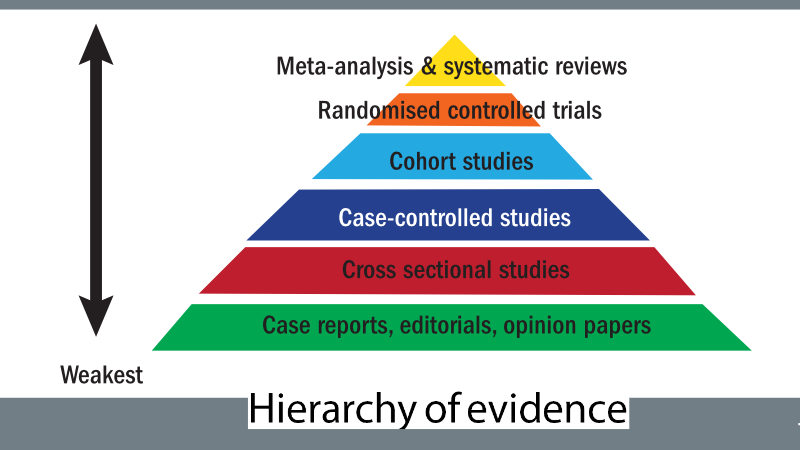

When reviewing research papers and study reports, it is important to have an understanding of what constitutes valid and reliable evidence. In terms of a single experiment that seeks to prove a hypothesis, then a randomised controlled trial is considered the best. However, a single study should never be taken as certain evidence until the experiment has been replicated many times with the same results. As a consequence, analyses that attempt to put together all the research into a particular question, so-called meta-analyses and systematic reviews, are considered the strongest evidence (figure 6).

To clarify further, let us consider each level in turn.

- Systematic review; results from many studies relevant to research question meeting specific quality criteria are appraised, results synthesised, and a summary of results created.

- Meta-analysis; results from many studies are pooled, and a statistical analysis performed on the data.

One of the benefits of systematic reviews and meta-analyses is they are apt to outline errors in previous work and also highlight where previous studies produce different outcomes to similar questions. For example, a paper reviewing 21 systematic reviews relating to open angle glaucoma treatments shows that nine of them use inappropriate statistical methods and demonstrates similar errors are perpetuated in future studies that seek to replicate the same results.11

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs); subjects are randomly allocated to a group. One group receives an intervention while the other does not, so acting as a control. Double blind means both the researcher and the subject are unaware of which group any subject is in. A single variable can be rigorously assessed, and the format minimises bias and allows for meta-analysis. However, RCTs are very expensive and require funding from large research bodies.

- Cohort study; compares groups of subjects and are observational. Longitudinal studies follow subjects for a number of years recording differences in any outcome. A downside is that subjects may drop out over a period of time.

- Case-controlled study; subjects with an outcome or disease are matched with subjects without the disease or outcome. This helps to identify risk factors.

- Cross-sectional study; an observational study taking a population sample at a specific point in time (snapshot) and collecting data to assess, for example, prevalence and associated risk factors.

- Case reports; reports of subjects who have had an intervention or exhibited an interesting behaviour, trait or presentation. Where more than one subject is considered, this format is referred to as a ‘case series’. Ideal for the starting point of any further investigation as, on their own, they cannot provide conclusive evidence.

- Editorials and opinions; an author’s position or opinion based on existing evidence, often an expert in a given field. Do not contain new information.

Figure 6:

Evidence relating to the practice of ophthalmic dispensing is generally low down on the hierarchy, largely because dispensing opticians are only just emerging as graduate professionals. There is, therefore, a lack of evidence from the apex of the hierarchy evidence pyramid, and the little that exists is largely carried out by optometrists and research scientists who, in the main, are less interested in dispensing than clinical optometry and contact lens practice. Therefore, the research consists mostly of literature reviews, case reports, opinion piece articles and research carried out by manufacturers.

Questioning the evidence

It is important to realise that researchers are unlikely to have posed themselves the same question that you are seeking the answer to and, even if they have, it may not have been legally or ethically possible to carry out an experiment that answers the question directly. This is especially true of questions relating to paediatric practice and maternity, where the healthy development of a foetus or baby could be impeded by an experimental intervention or lack of the usual treatment.

When reviewing research evidence, it is important to ask questions such as:

- What is the purpose of the study?

- Is the evidence from a reliable source?

- Is it relevant to my patients?

- Has the evidence been reviewed?

- How old is the evidence?

- What is the study design?

- Accurate measurements?

- Can it be duplicated?

- Is there likely to be any bias?

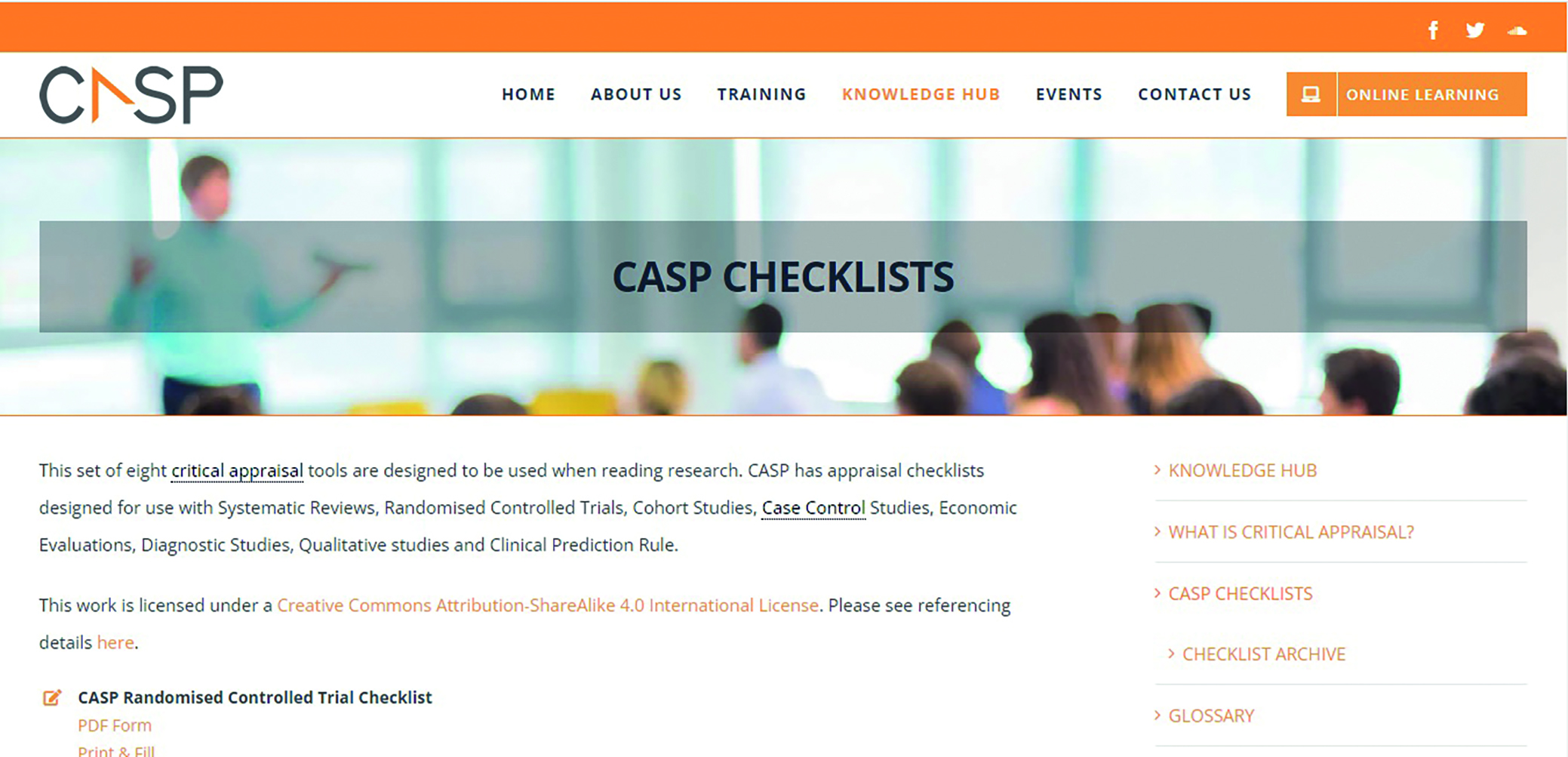

Critical thinking skills can be honed through the use of standard tools and checklists such as those provided by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), which provides a series of tools relevant to each type of study design at https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (figure 7).

Figure 7: The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) provides a series of tools relevant to each type of study design

Another well-known appraisal method is the CRAAP test:

C: Currency, date of publication. If a website, when was it last updated?

R: Relevance. Is the information/research relevant to your topic?

A: Authority. Is the author known, a recognised specialist in this topic?

A: Accuracy. Is the article peer-reviewed or the information supported by references?

P:Purpose. What is the aim of the article or information? Is it commercial?

It is always worth remembering that if something seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Comparing papers – myopia management

A hot topic of research in the fields of dispensing optics, contact lens practice, optometry and ophthalmology at the moment is myopia management. This has been written about extensively in this publication, and will be covered further in some detail in a future article in this series with the aim of bringing readers up to date from an ophthalmic dispensing perspective. However, it is useful to take a look at how different research is presented and consider three relatively recent papers that are all available via open access.

Figure 8: Recent papers on myopia control

The papers pictured in figure 8 are all open access papers cited in a recent CET webinar relating to myopia management. They are:

- Lam et al. 2020; Defocus incorporated multiple segments (DIMS) spectacle lenses slow myopia progression: two-year randomised clinical trial (double blind)

- Chamberlain et al. 2019; A three-year, randomised clinical trial of MiSight for myopia control (multicentre, double blind).

- Cooper et al. 2018; Case series analysis of myopic progression control with a unique extended depth of focus multifocal contact lens. Retrospective real-world evidence.

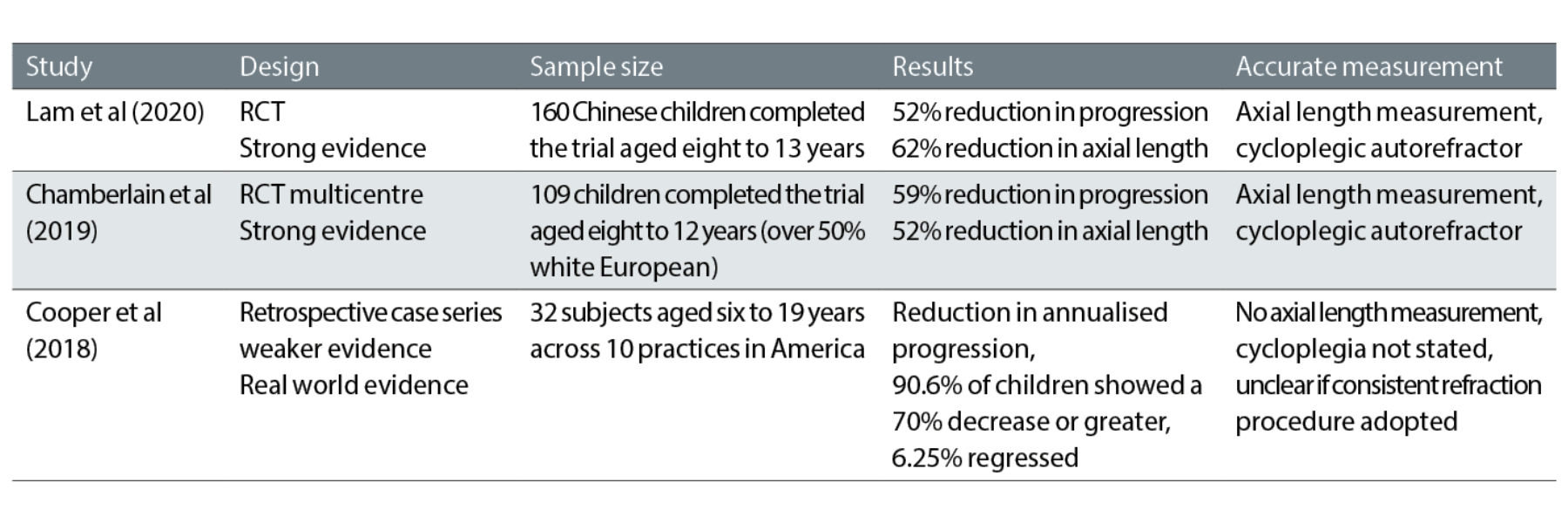

In table 2, differences between the three papers are highlighted.

Readers are encouraged to access all three papers for themselves and not to take these authors’ words for granted. However, it becomes apparent that what is said can be very confusing. For example, in table 2, it states that axial length is reduced when, in fact, it means the rate of growth of axial length is reduced by approximately half. In other words, if in a given time the children’s eyes would have been expected to have lengthened by say 1mm, then the interventions tested lead to the growth slowing to around 0.5mm. Similarly, if the control group might be expected to have shown myopic progression of -1.00DS in a certain timescale, then the group receiving myopia control interventions might be expected to have progressed by only -0.50DS

approximately.

It does not take too much time honing your appraisal skills to start to pick holes in the research. For example, is it fair to compare studies of entirely Chinese children with those relating to children with a variety of ethnic heritages? Do the numbers of subjects need to be above a certain level to be statistically

significant?

Much is made in one study of the regression of myopia in a small minority of subjects, as though this somehow demonstrates the efficacy of the intervention when, actually, it could potentially be that the child had an incorrect refraction at the first consultation (over-minused, as commonly happens especially with autorefractors and children not subject to cycloplegia) and at the second refraction was given the correct prescription. Even if the myopia had regressed it would be useful to have an explanation of how that might be possible since it would mean that either the eye had grown shorter or the cornea flatter (or both), both of which seem unlikely.

Table 2: Comparison of three papers on myopia management

Statistics

Statistics can be a daunting subject and it sometimes appears researchers have set out to deliberately confuse. However, there are a host of free websites dedicated to explaining statistics including the Khan Academy (www.khanacademy.org) and www.mathsisfun.com.

Here are a few important statistical terms we all should be familiar with.

- Averages:

- Mean; the total of all values divided by the number of

values - Median; the middle value (or average of two middle values) when all values are arranged sequentially in size

- Mode; the most common value in any series of values

- Variance; a measure of the variability of any property, it is the average of the squared difference from the mean of the values of that property

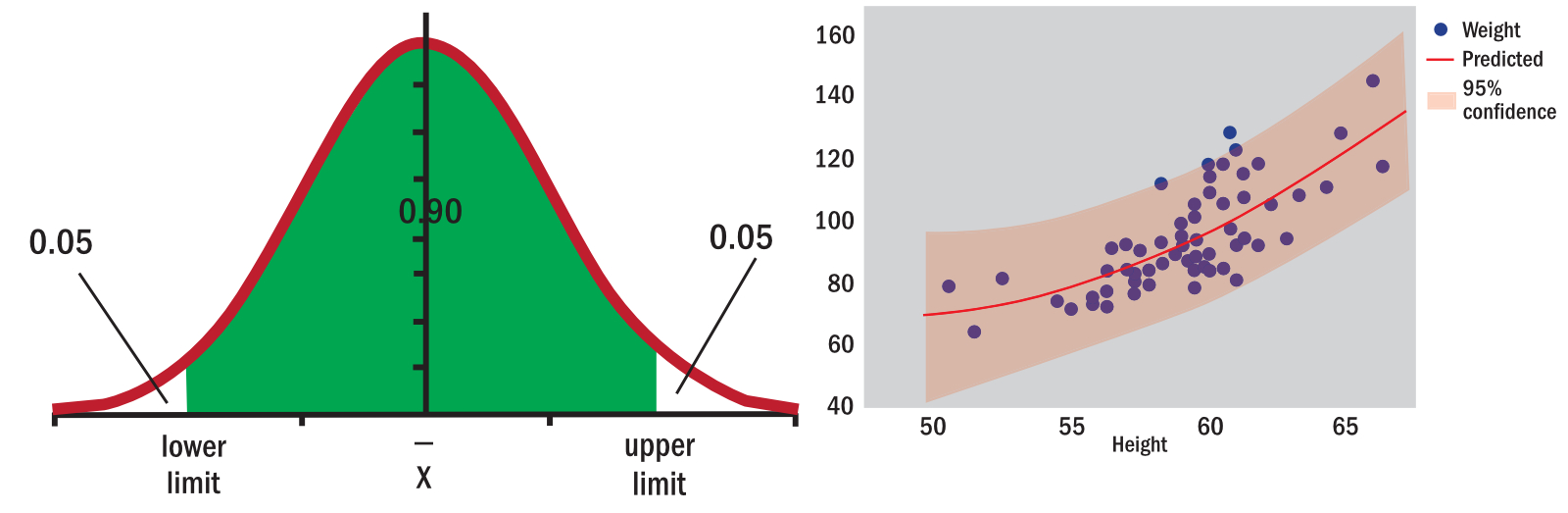

- Normal distribution; a classic bell-shaped graph that applies to many datasets (figure 9)

- Standard deviation; the square root of the variance

- Mean; the total of all values divided by the number of

- Confidence interval:

- How confident we are that the true answer lies within the range of sample data

- The smaller the interval (or range), the more confident you can be that the study reflects results you would find in a larger population

- A 95% confidence interval means we can be 95% sure the true value for a population (such as prevalence of a disease) lies between the lower and upper confidence interval range (figure 10)

- P-Value; the probability value, indicating the probability that any particular set of results were down purely to chance. The lower the number the better the probability. A few points worth remembering include;

- Look for a value under 0.05

- Where p = 0.05, there is a 1 in 20 chance that the results were just down to pure luck

- Robust research looks for p<0.01 (less than 1 in 100 chance of pure luck)

- Be suspicious of p = 0.00000 (there is never zero chance of serendipity; remember the infinite monkey cage)

- This is a common indicator of a presenter’s statistical acumen; the authors have seen p = 0.5 on a slide at a CET conference, suggesting a result which had a 50% chance of being arrived at by pure luck.

Figure 9: A normal distribution curve; Figure 10: Predicting confidence values

Conclusions

Evidence-based practice ensures eye care practitioners stay up to date, informs clinical decision-making and helps to keep the patient at the centre of all decisions. It enables practitioners to critically appraise new research, and new products that are introduced on the back of such research, objectively. Practitioners must make time for reviewing clinical and research literature cited in journals, textbooks and magazines, which combined with clinical experience facilitates the application of clinical reasoning.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO AFHEA is Course Lead for BSc (Hons) Ophthalmic Dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, board member and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians.

- Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CPD provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College.

References

- General Optical Council. Keep your knowledge and skills up to date. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. London : GOC, 2016, p. 10.

- GOC. Obtain valid consent. General Optical Council. [Online] April 1, 2016. [Cited: June 12, 2022.] Standard 3. Obtain valid consent. https://optical.org/media/201flx0e/standards_of_practice_for_optoms_dos.pdf.

- Medical Classics Dr Spocks. BMJ. [ed.] Elizabeth Loder. 339, s.l. : British Medical Association, July 14, 2009, British Medical Journal.

- Interaction between bedding and sleeping position in the sudden infant death syndrome: a population based case controlled study. Fleming, P J, et al. s.l. : British Medical Association, 1990, BMJ, Vol. 301, pp. 85-89.

- Major epidemiological changes in sudden infant death syndrome: a 20-year population –based study in the UK. Blair, P S, et al. 9507, 2006, The Lancet, Vol. 367, pp. 314-319.

- GOC. Education Strategic Review. General Optical Council. [Online] March 16, 2022. [Cited: June 12, 2022.] https://optical.org/en/education-and-cpd/education/education-strategic-review/.

- ABDO College. BSc (Hons) Vision Science. [Online] 2017. [Cited: June 13, 2022.] ttps://abdocollege.org.uk/news/bsc-hons-vision-science/.

- Aston University. Doctor of Optometry / Doctor of Ophthalmic Science DOptom/DOphSc. Aston University. [Online] [Cited: June 13, 2022.] https://www.aston.ac.uk/study/courses/doctor-of-optometry-doctor-of-ophthalmic-science-doptom-dophsc/january-2000.

- Straus, G E, et al. Evidence-Based Medicine. 5th. Edinburgh : Elsevier, 2019. p. 1.

- Hoffmann, T, Bennett, S and Del Mar, C. Evidence-Based Practice. 3rd. Australia : Elsevier, 2017. p. 4.

- Li T, Dickersin K. Citation of previous meta-analyses on the same topic: A clue to perpetuation of incorrect methods? Ophthalmology. 2013;120(6):1113–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4730544/