The first two parts of this series offered an overview of autistic visual sensory experiences and the challenges faced by autistic people in accessing adequate and appropriate eye care.

Is Healthcare Accessible for Autistic People?

Autistic children and young adults are 11 times more likely,1 and autistic adults five times more likely2 to develop poor health compared to the general population. Therefore, it is unsurprising that autistic people are expected to access healthcare more often.3-6 However, significant issues surround healthcare provision to this population.7,8

A survey conducted by the Westminster Commission on Autism9 found that 74% of autistic, parent-advocate and professional respondents felt that the autistic population receives poorer healthcare than non-autistic people. This could be because some of the physical symptoms of health issues presented by autistic people are erroneously attributed to features of autism instead.10

In comparison to non-autistic people with or without other disabilities, autistic individuals experience greater barriers to accessing healthcare,11 and potentially eye care services specifically. Raymaker et al11 found that the top five barriers to healthcare for autistic people were: fear and anxiety, slow information processing, which means they cannot have a real-time conversation with healthcare professionals, cost implications, sensory issues, and communication issues with service providers.

Interviews conducted by Nicolaidis et al12 with autistic adults and individuals who supported autistic people in a healthcare setting concluded autism-related factors, such as verbal communication deficits and sensory sensitivities impacted service use on the part of the patient. Lack of autism knowledge, incorrect assumptions about abilities of patients and unwillingness to adapt created barriers from the part of service providers. The complexity of the healthcare system, physical features of healthcare settings and stigma about autism created system-level barriers.

Dern and Sappok7 arranged meetings involving autistic adults, who could verbally share their personal experiences, and autism professionals, who spoke on behalf of autistic adults who could not verbally share their experiences. These discussions highlighted that the sensory and communication issues surrounding autism need to be understood by service providers to make sure that their services are autism-friendly. Some of these appear very relevant to the eye care setting.

For example, arranging appointments by phone call is difficult for autistic people. Proximity to strangers, sensory issues and stress due to uncertainty create challenges in waiting areas. Sudden touch during the examination causes discomfort. Communication during appointments is testing due to literal thinking, lack of time to think and respond to questions and general issues with communication. Saqr et al13 conducted focus groups with autistic people, and found that the key issues associated with stress during a medical appointment were sensory issues, anxiety and lack of mutual understanding, communication and trust. Communication was perceived to be poor on the part of the practitioner.

In the previous article (see Optician 26.08.22), we explored the key concerns that autistic adults have about eye care services. Autistic adults can face barriers throughout accessing eye care: booking the examination, arriving at the practice and undergoing various tests with different staff members.14 The combination of these factors creates significant anxiety and stress, causing some autistic adults to avoid important eye care. When considering how to improve eye care accessibility for autistic people, the service needs to be reflected upon holistically.

Multiple Eye Tests, Multiple Challenges

The eye examination is at the core of eye care, assessing different ocular functions and eye health. It is important that tests are understandable and comfortable for patients so that optometrists can gain accurate information. The variety and number of tests employed by an optometrist can pose various challenges for autistic adults. Tests involve strong sensory stimuli, close proximity and decision-making. These factors can cause stress and anxiety for autistic adults.14 Although it may not be possible to eliminate these challenges, optometrists can consider how they could be reduced. To facilitate this, Parmar et al14 provided thorough eye examinations for 24 autistic adults and simultaneously interviewed them to understand the following:

- a) What they liked about the way tests were carried out

- b) What they did not like about the tests

- c) What could be improved about the way the tests were conducted

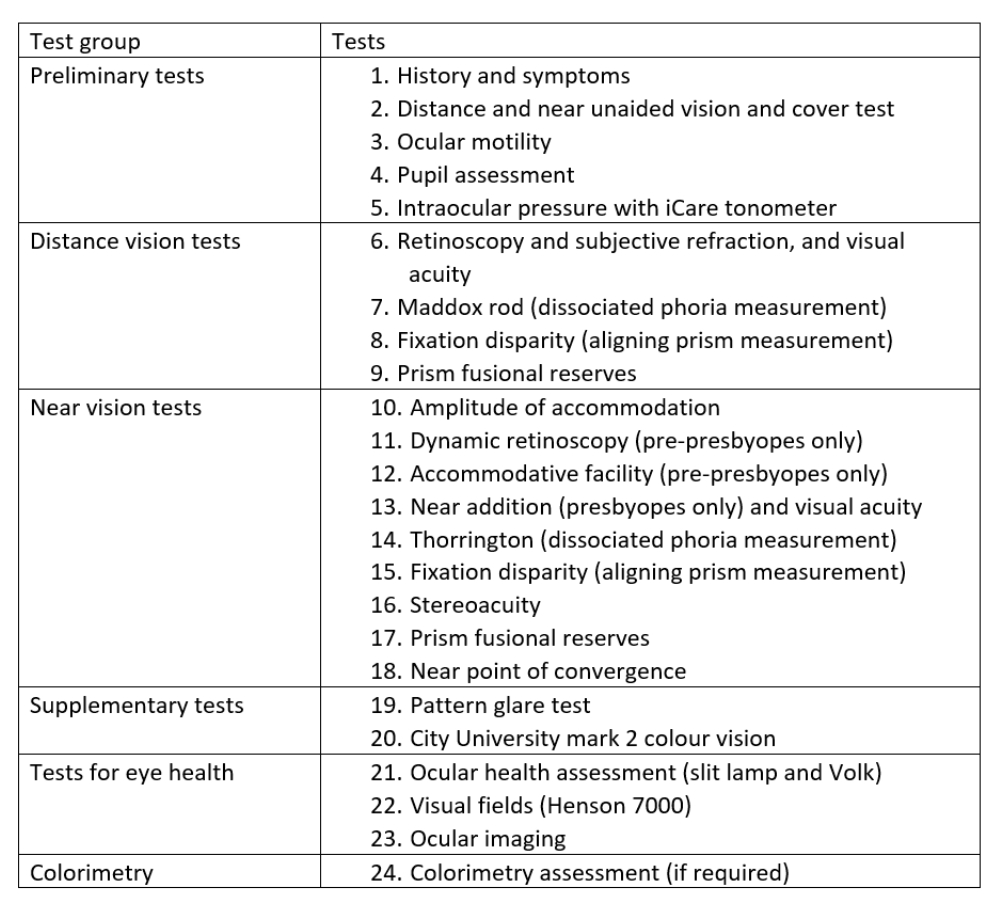

A variety of tests were conducted (table 1), all common in everyday optometric practice. Before each test, the optometrist told participants what the test was for, what would be involved and what the participant was required to do, if anything.

Table 1: The tests (in order) conducted during eye examinations for autistic adults as part of a study by Parmar et al.14 Participants were presented with three interview questions after each test group

Taking pupil assessment as an example (figure 1), participants were told: ‘In the next test I will be checking your eyes’ reaction to light and I will need to lower the room lights for this. This involves me shining this bright light into your eyes [showing participant pen torch] and your job is to keep looking straight into the distance.’14

Figure 1: Tests involving bright lights, such as pupil and slit lamp assessment, can trigger pain and be difficult to handle

Eye-test specific feedback from autistic adults

Overall, autistic adults enjoy eye examinations because of the variety of tests and equipment used. The process does not feel monotonous, and is quite fascinating.14 Knowing what to expect during an eye examination is particularly useful for autistic people:

“I never would have thought, prior to finding out about my autism and everything, that this sort of stuff would be helpful for me… I’m surprised how much less anxious I feel…it just takes a little bit of the load off.”14

Receiving ‘what to expect’ information in advance of the appointment date allows autistic people to come prepared for the variety of tests they will undergo, the different rooms they will visit and who they will meet. They can therefore have greater capacity to deal with any other unexpected occurrences. For those who regularly go for eye examinations this information serves as a useful reminder. Photos and videos should be used alongside text descriptions. Autistic adults have described such information to have ‘…allayed any fears there may have been.’14

The remainder of this section will discuss the feedback received by Parmar et al14 from autistic adults, question-by-question.

Are there any tests that you did not like? Why?

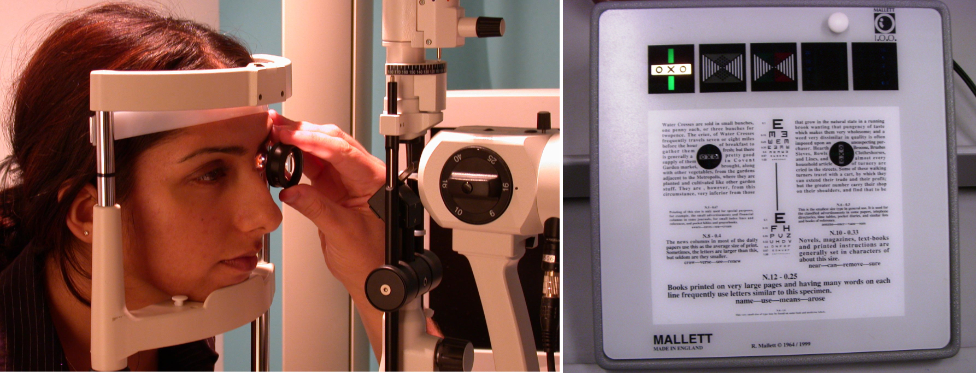

Altered sensory reactivity is experienced by the majority of autistic people.15, 16 This can involve an increased or reduced sensitivity to sensory stimuli; see part 1 of this series (see Optician 29.07.22). Sensory experiences cause significant stress for autistic people, and this is no different during an eye examination. Tests involving bright lights, such as pupil and slit lamp assessment, can trigger pain and be difficult to handle:

“I didn’t like the ones where you’ve got bright lights in your eyes like the flash and this machine here [slit lamp]. I sort of had to tense myself to cope with it…it was at the edges of what I could tolerate.”14

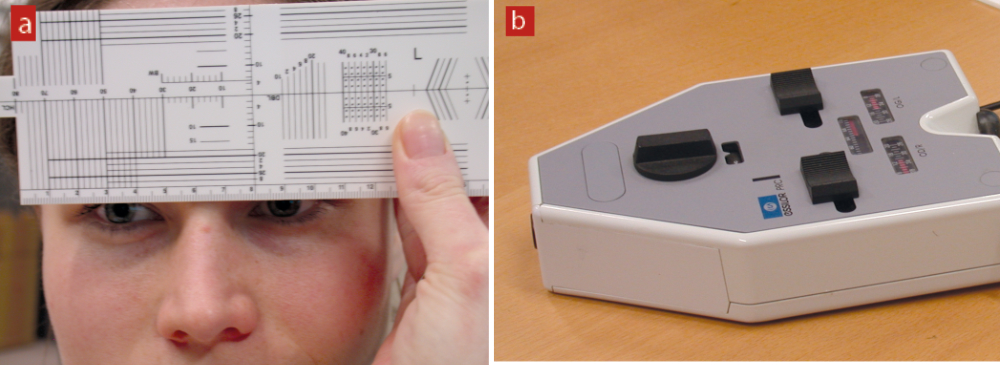

Figure 2: Measuring PDs, either by (a) a rule or (b) a pupillometer, can be uncomfortable because of the measuring tool being cold

Some tests require physical contact, for example an RAF rule or pupilometer (figure 2). But these can be uncomfortable because of the object being cold. Instruments which have a narrow area of contact can feel more intrusive. Autistic adults can prefer firm, obvious contact rather than ‘hovering’ contact, for example when a Volk lens is held close to the eye or the irritating sensation of iCare tonometry (figure 3).

Figure 3 & 4 (left to right): Autistic adults can prefer firm, obvious contact, as with the fingers here, when rebound tonometry is undertaken; An image of a Mallett unit which can be used to assess near vision and fixation disparity. When assessing one visual function, the other features of the Mallett unit can be a distraction for autistic adults14

Studies have suggested autistic people struggle to ignore irrelevant sensory stimuli,17-20 and have impaired attention.21 Autistic adults have described difficulty attending to their central vision and ignoring stimuli in the peripheral field.17 In terms of eye examinations, this impacts autistic adults’ ability to concentrate on tests that have other targets around the fixation point, for example when assessing near vision or fixation disparity using the Mallett Unit (figure 4). Participants in Parmar et al14 commented on measuring amplitude of accommodation using the RAF rule (figure 5): ‘…I found the words underneath [the N5 print line] too distracting ’cos my eye is generally drawn elsewhere.’14

While Parmar et al14 gave an explanation of the tests and what would be involved, participants commented that they would have preferred to have seen what was going to be held in front of their eyes such as the cross-cylinder or occluder. Although participants could see the RAF rule when amplitude of accommodation was being assessed, some felt that the target being brought closer felt intrusive. Evidently, tests requiring close proximity, of practitioner or instrument, are not popular among autistic adults. Although this can be expected for non-autistic people too, such tests cause significant stress and anxiety for autistic people.

Figure 5: An RAF rule set up to measure amplitude of accommodation. Although directed to concentrate on the N5 print, the other text can be difficult to ignore for autistic adults14

Was there anything you liked about the way in which these tests were carried out?

Good communication is important for all optometric patients. A recent study by Kim et al22 concluded that better optometrist communication resulted in better patient satisfaction, among a general Korean population. Autistic adults have described low satisfaction with patient-practitioner communication.8, 11

Communication challenges cause stress for autistic people during medical appointments.13 Autistic adults largely appreciate clear explanations during eye tests: what the test is for, what would be involved and what they are required to do. Being told when bright lights would be used, if there would be any physical contact or close proximity is helpful: ‘I understood what was happening, I understood the purpose for it so that put me at ease and I could understand the reasoning for it.’14

Additionally, using visual guides to explain some tests, such as pointing a pen torch in the direction the patient should be looking, gives autistic adults confidence that they are following instructions correctly. Giving a demonstration of tests, for example the experience of diplopia when measuring prism fusional reserves, allows autistic adults to fully understand what to expect ‘…rather than just being thrown into it.’14

Autistic adults can think very literally,3 and in the previous article we discussed the implications of this on test instructions. To recap, optometrists need to provide clearer instructions for subjective tests, and mention if no difference or improvement in vision should be expected. For example, during cross-cylinder assessment, optometrists commonly ask: ‘Are the circles rounder and sharper with lens 1 or 2?’ Autistic people can interpret this as there must be a difference between the two options, subsequently becoming distressed if they are not noticing it. Rather, the optometrist should ask: ‘Are the circles rounder and sharper with lens 1 or 2, or about the same?’ (figure 6):

“One thing that definitely made a big difference was actually telling me that I should be aiming for no difference, because normally opticians don’t tell you that. They just say ‘can you see a difference’ but they don’t tell you that you are supposed to be aiming for a point when there is no difference…it is very stressful for the autistic person because you are looking for a difference that isn’t there…”14

Figure 6: The optometrist should ask ‘are the circles rounder and sharper with lens 1 or 2, or about the same?’

Autistic adults appreciate the opportunity to ask questions when they have difficulty understanding instructions: ‘I like that I’ve been able to ask questions without feeling that I’m wasting your time too much.’14 They also like being told test outcomes as the examination progresses, and especially seeing results being interpreted from images and plots: ‘I liked seeing the results from scans and you describing what the retinal scans…and the layers at the back of the eye were.’14

Optometrists being aware of patient comfort has a significant impact on autistic people’s experience of eye examinations. Autistic adults value optometrists having a reassuring tone and paced voice, allowing them to better process what they are being told: ‘If you have a clinician who speaks to you quite abruptly it’s very, very difficult to feel comfortable.’14 Not being under pressure to have to respond and complete tests ‘ultra-quickly’ makes autistic people feel relaxed. They also appreciate the option to take a break if feeling overwhelmed.

Finally, some autistic people prefer holding instruments themselves, such as near vision charts and the Mallett unit, giving a sense of control: ‘I feel a lot more comfortable when I’m holding something and looking at it myself.’14

What could have been improved about the ways these tests were conducted?

Although Parmar et al’s14 participants were satisfied, they provided further tips to enhance practitioner communication. Informing how long tests would approximately take, if equipment is not working and allowing them to handle equipment before it is used are methods of allowing autistic people to feel more relaxed during an eye examination. Autistic adults prefer very specific questioning rather than having to assume even the slightest detail: ‘…what if I’m paying attention to the wrong dynamic in this visual thing, and so I’m giving you wrong information so you get the wrong prescription?’14 To help avoid such confusion, optometrists could show autistic patients printed examples of what they may experience during subjective tests, such as different presentations of the Mallett unit OXO (figure 7).

Figure 7: Printed examples, such as the various Mallett outcomes, can help to clarify test outcomes

These could also be used to help autistic patients describe what they are experiencing during the tests: ‘It would have been interesting to see some examples of what other people experience with the [pattern glare test]…and say “is it anything like this?”’14

Autistic adults have recommended rearranging the order of eye tests, with more demanding tests conducted earlier in the examination. The effort required to respond to a variety of eye tests can be draining for autistic people, impacting their ability to concentrate and respond progressively. Referring to prism fusional reserves, a participant in Parmar et al14 said:

“I think that test is quite hard to do at the end of all these other tests, is it possible to do it earlier on? Anything that requires quite a lot of explanation about what you’re doing I think is easier to do when you’re less tired.”

Although sensory issues cannot be eliminated, simple changes can reduce the impact. For example, when instilling eye drops, autistic people can be asked if they would like to hold their own eyelids. During slit lamp examination, autistic people should be allowed to take an optional break from the bright light. Sudden bursts in noise outside the consulting room can be distracting, but this could be overcome with ‘…some constant [white] background noise, whether it was sort of waves of a sea…just something to amalgamate all the sounds together.’14

Key messages

It is easy to forget the complexity of an eye examination. Although an interesting process, the variety of tests introduce multiple challenges for autistic adults, all overarched with stress and anxiety. A crucial tool to help reduce these is good practitioner communication: providing clear instructions, asking specific questions, and having a reassuring and paced tone. Optometrists should be aware of patient comfort, realising the impact this can have on the course of the examination. Although sensory issues are expected due to the nature of many eye tests, reasonable adjustments can be made to reduce these.

The final article will bring together all that has been covered in this series, and discuss some recommendations for providing autism-friendly eye care.

- Dr Ketan Parmar is a research optometrist at Eurolens Research, and Optometry Clinical Tutor for the undergraduate Optometry degree programme at the University of Manchester.

For a range of free-to-download resources, go to: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/autism-and-vision/eye-care-provider-resources.

References

- Rydzewska E, Hughes-McCormack LA, Gillberg C, Henderson A, MacIntyre C, Rintoul J, et al. Age at identification, prevalence and general health of children with autism: observational study of a whole country population. BMJ open. 2019;9(7):e025904.

- Rydzewska E, Hughes-McCormack LA, Gillberg C, Henderson A, MacIntyre C, Rintoul J, et al. General health of adults with autism spectrum disorders – A whole country population cross-sectional study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2019;60:59-66.

- Mason D, Ingham B, Urbanowicz A, Michael C, Birtles H, Woodbury-Smith M, et al. A Systematic Review of What Barriers and Facilitators Prevent and Enable Physical Healthcare Services Access for Autistic Adults. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2019;49(8):3387-400.

- Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U. Emergency department use among adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(4):1441-54.

- Weiss JA, Isaacs B, Diepstra H, Wilton AS, Brown HK, McGarry C, et al. Health concerns and health service utilization in a population cohort of young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(1):36-44.

- Zerbo O, Qian Y, Ray T, Sidney S, Rich S, Massolo M, et al. Health care service utilization and cost among adults with autism spectrum disorders in a US integrated health care system. Autism in Adulthood. 2019;1(1):27-36.

- Dern S, Sappok T. Barriers to healthcare for people on the autism spectrum. Advances in Autism. 2016;2(1):2-11.

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, Dern S, Boisclair WC, Ashkenazy E, et al. Comparison of Healthcare Experiences in Autistic and Non-Autistic Adults: A

- Cross-Sectional Online Survey Facilitated by an Academic-Community Partnership. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(6):761-9. Christou E. A Spectrum of Obstacles: an enquiry into access to healthcare for autistic people. Huddersfield: The Westminster Commission on Autism; 2016.

- Sala R, Amet L, Blagojevic-Stokic N, Shattock P, Whiteley P. Bridging the Gap Between Physical Health and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2020;Volume 16:1605-18.

- Raymaker DM, McDonald KE, Ashkenazy E, Gerrity M, Baggs AM, Kripke C, et al. Barriers to healthcare: Instrument development and comparison between autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. Autism. 2017;21(8):972-84.

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, McDonald KE, Dern S, Baggs AE, et al. “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2015;19(7):824-31.

- Saqr Y, Braun E, Porter K, Barnette D, Hanks C. Addressing medical needs of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders in a primary care setting. Autism. 2017;22(1):51-61.

- Parmar KR, Porter CS, Dickinson CM, Pelham J, Baimbridge P, Gowen E. Autism-friendly eyecare: Developing recommendations for service providers based on the experiences of autistic adults. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2022;42(4):675-93.

- Green D, Chandler S, Charman T, Simonoff E, Baird G. Brief report: DSM-5 sensory behaviours in children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(11):3597-606.

- Kientz M, Dunn W. A Comparison of the Performance of Children With and Without Autism on the Sensory Profile. The American journal of occupational therapy. 1997;51(7):530-7.

- Parmar KR, Porter CS, Dickinson CM, Pelham J, Baimbridge P, Gowen E. Visual sensory experiences from the viewpoint of autistic adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12.

- Smith RS, Sharp J. Fascination and isolation: A grounded theory exploration of unusual sensory experiences in adults with Asperger syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2013;43(4):891-910.

- Adams NC, Jarrold C. Inhibition in Autism: Children with Autism have Difficulty Inhibiting Irrelevant Distractors but not Prepotent Responses. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(6):1052-63.

- Christ SE, Kester LE, Bodner KE, Miles JH. Evidence for selective inhibitory impairment in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(6):690.

- Liss M, Saulnier C, Fein D, Kinsbourne M. Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism. 2006;10(2):155-72.

- Kim S-J, Sim J, Kim H. Effects of the Communication and Professional Technical Skills of Optometrists on Customer Satisfaction. J Korean Ophthalmic Opt Soc. 2020;25(3):219-25.