Communication is so much more than words. Effective patient communication can benefit all areas of practice, from improving clinical outcomes to making more efficient use of our time, and from increasing patient value to building loyalty. Success in attracting and retaining patients as valuable customers can turn on a single conversation with any one of your practice team.

Reflect for a moment on an occasion when you’ve received excellent service. Besides exceeding your expectations, your experience may have created loyalty, recommendation and a better understanding of the service you received. The chances are that communication was a key part of this experience.

In the same way, every interaction with a patient provides us with a multitude of opportunities to communicate, and the potential either to do it adequately, or to really build a rapport. While we may all like to consider ourselves as proficient communicators, our patients may well disagree.

Identifying what to look and listen for is the first step towards more productive conversations in practice. But it’s important to keep in mind the old cliché that any conversation is a two-way process; being understood is a combination of what you say and do, and how others respond.

Effective communication will benefit you, your patients, your practice and your team. The outcome for all is the same: excellence in eye care and eyewear.

[CaptionComponent="114"]Routine isn’t routine

It’s often the tiniest changes that have the most impact. A subtle change to a single word, different intonation or volume, alternative body language, how and when you deliver a phrase – each, any and all of these elements will impact on the patient’s interpretation of a conversation and their consequent responses.

Most of our contact is carried out, to some degree, on autopilot. Most of what we do, what we say and how we behave – in fact how we choose to communicate – is indeed ‘routine’. This is understandable when the patient might be the 10th you’ve seen that day but, from the patient’s perspective, it could be two years or more since their last visit. For patients, their visit is the only consultation their practitioner has that day.

Because we’re trained to recognise signs and symptoms, we learn to listen and respond automatically. We tend to say less or ask fewer questions to investigate, whereas the patient may want and expect us to say more.

Treating each patient as an individual, and recognising that the way we conduct our conversations needs to be tailored to their needs, is essential to getting the most out of every relationship.

Instead of thinking ‘treat others how you want to be treated’, think ‘treat your patients how they want to be treated’.

Understanding how you are perceived by others, your personality, distinctive interaction style and reputation, can also help identify your own strengths and weaknesses, and improve your communication skills.

Put down the comfort blanket

In the consulting room, most practitioners begin an appointment with the same well-oiled line or phrase, which is like a comfort blanket. That opening gambit is a selection of words, said in a specific tone or manner, which is often accompanied (in our own minds at least) by a comforting facial expression. We want to create the right impression of ourselves and our practice: to be friendly, open and welcoming, but also professional and trustworthy.

We may have experimented with a few options along the way, but once we find the phrase that works we tend to keep it. It takes the examination down a predictable route and sets us off once more on our well-travelled course.

Using stock words and phrases, while often well meaning, lacks the sincerity of a genuine conversation. We all know someone whose standard response to anything is ‘lovely’ or ‘great’, regardless of the situation. ‘Take a seat – I’ll be right with you’, is another example, whether you’ll be right with them or not! Without context and meaning, such statements risk becoming the ‘Have a nice day’ we all know and ignore.

These comfort blankets extend beyond the consulting room, to the reception desk, the office, the dispensing area; in fact they are found all over the practice and are individually loved by each member of staff. You may find it easy to identify them when used by your colleagues yet struggle to recognise and acknowledge this trait in yourself.

The problem with any comfort blanket is that over time it becomes worn and old, and parting with it is challenging. Sometimes, to make improvements, we have to be brave and try an alternative approach.

Build rapport

Instead of fitting the patient in to your ‘routine’, think about establishing a relationship with each individual in a similar way that you would in social situations. Rapport is the process by which two people become mutually responsive to each other and is the key to every successful interaction.

Building a rapport with your patient will give you better information which, in turn, helps you make better decisions and higher quality recommendations. You know you have achieved rapport when your patient tells you what they think and why. They will also tell you how they feel.

You achieve rapport through active listening, which demonstrates empathy and the full consideration of others. It also satisfies the clinical argument to include patients in decision-making. This is because rapport creates the conditions in which patients feel more enabled and empowered.

If the patient understands more about what’s happening (and why), your recommendations for eye care and eyewear become more informed choices, agreed between both parties.

Psychologist Will Schutz describes a human element to communication in a way that stresses three factors underlining rapport: the need to feel significant, competent and likeable.1 The more we recognise these needs in our patients the more skilful we will be at meeting them.

Step back and consider what you want from your consultation; as full a picture as possible of your patient’s health, vision and any recent changes that could impact on the examination, and all within a short time span. Spending time thinking about how you establish and maintain rapport with your patient will improve how you use your time and the quality of the conversations you have.

[CaptionComponent="115"]See the bigger picture

There is of course, a ‘bigger picture’ when it comes to communication during an examination. Yes, we need to elicit information, but it’s not just about asking questions. It’s about the accuracy and relevance of the information we are retrieving.

Small changes to your listening and questioning techniques that allow patients to voice their opinions and feelings, and to agree an agenda before and during the consultation, can make a big difference in avoiding distorted messages and misinterpretation.

While the practitioner absorbs the information and considers the answers given, the patient may think: ‘I’ve answered all the questions but feel as if I’m being ignored.’ With some eye examination procedures, patients may wrongly believe there to be a right or wrong answer (‘one or two’, ‘red or green’) and need reassurance accordingly. This may be one of the few examinations they undergo where the answer ‘I don’t know’ (or ‘no difference’) is acceptable (or even welcome).

We’re also required to give information back, be it good news or bad, in a format that the patient can understand and accept. We need to deliver advice and instructions in such a way that they are likely to be followed. It’s all too easy to blame patients for not doing as they’re advised, but it may be our own ability to communicate these requirements that is actually at fault.

Communication skills are now an integral part of training and a core competency for professional staff, yet are often neglected. Many complaints received by regulatory bodies centre around failure to communicate or breakdown in relationships. The highest levels of knowledge and practical skill will have only limited benefit if powers of communication are lacking.

Perhaps the biggest challenge that faces us as practitioners is to remember that the things we do routinely, over and over again, day in, day out throughout our careers, is anything but routine for our patients. They need to know they have your full attention and that their own specific concerns are addressed.

[CaptionComponent="116"]Take a patient-centred approach

Dr Fiona Fylan is a health psychologist who has worked extensively on communication in eye care. She explains that there is increasing recognition of the importance of a patient-centred approach.2 ‘This involves the patient and eye care practitioner working in partnership to agree the best outcome for the patient and how to achieve it.’

The practitioner contributes their clinical knowledge and experience while the patient is an expert on their own requirements, expectations and lifestyle. In contrast, in the more traditional, paternalistic approach, the practitioner identifies the ‘best’ outcome from their own perspective and gives the patient instructions about what needs to be done to achieve that outcome, she says.

Many of the basic principles of effective communication apply to every patient interaction, whatever your role and responsibilities within the practice team and at all stages of the patient journey.

Optometrist Andrew Millington has examined how models of health consultation apply to eye care. He points out that while it may be tempting to divide the optometric consultation into three distinct stages – history and symptoms, examination and ‘disposal’ – this is a very doctor-centred approach.3

‘Although an eye examination falls naturally into these three phases we need to look at them as part of the whole patient experience,’ says Millington. ‘It’s worth remembering that, from the patient’s point of view, the experience starts with booking the appointment and ends when they return home; it’s not simply the half hour spent in the consulting room.’

Table 1 lists just some of the principles commonly put forward for effective communication, both verbal and non-verbal, that can be applied throughout the patient journey.

Skilled communicators know the importance of key points of contact within each patient interaction; from the initial call to book an appointment to the first greeting on entering the practice, and from the final ‘sign off’ on leaving to a follow-up call to check on progress. The handover between each member of the team is also crucial.

Staff training should address all these issues and involve the whole team. Interactive exercises, such as role-playing or observing real-life conversations in practice, are an ideal learning format for communication skills.

Staying in contact

Contact lenses are an area of practice where these principles are arguably even more important and in which every member of the practice team has a role to play, starting from the initial telephone enquiry and first face-to-face interaction.

With new contact lens wearers, lack of information about what’s involved and apprehension about touching or putting something ‘in’ the eye means that there are greater barriers to overcome. Establishing trust and rapport from the outset is crucial to success, since positive initial experiences can help to avoid dropout in the early stages of lens wear.

There can be emotional, social or psychological reasons for trying contact lenses. You may discuss personal issues, such as how they feel about their appearance or how they’re viewed by others. Their interest in contact lenses may be sparked by defining moments in their lives, such as changing schools or getting married, that they might not otherwise discuss during the course of an eye examination.

With more frequent visits, more contact and the need for constant reinforcement of wear and care procedures, the ongoing relationship between the contact lens practitioner and wearer is often closer than with other patients. The clinical consequences of a breakdown in communication can therefore be serious and the importance of professional care needs to be clear.

The personal rapport needed during the contact lens teach may be stronger still given the physical and emotional barriers involved. Trying, and failing, to handle lenses for the first time in front of someone else is a daunting proposition for any patient.

Seek concordance, not compliance

Poor compliance is heavily influenced by inadequate or infrequent communication. Helping patients understand the advantages and consequences of key compliance behaviours, then supporting verbal advice with written instructions is known to enhance compliance.6,7

Try thinking about gaining ‘concordance’ rather than compliance – this requires you to ask more questions, understand motivation and use more persuasive language. Talk about the positive outcomes of complying with wearing schedule, lens replacement or cleaning: they are more likely to enjoy better vision, comfort and continue wearing lenses. Patients will agree and want to take action on what you recommend.

Optometrist and staff training consultant Sarah Morgan argues that applying the principles of social interaction can also improve compliance in contact lens wearers.7,8 ‘Don’t criticise, condemn or complain,’ she observes. ‘This serves only to alienate the patient towards the practitioner and should be avoided.’

Being genuinely interested in patients and their interests, and making them feel important by inviting their feedback on a new lens or solution, are just some of her tips for enhancing interaction with contact lens wearers and making them more receptive to advice.

Consider the barriers to conversation from a patient perspective:

[CaptionComponent="117"][CaptionComponent="118"][CaptionComponent="119"][CaptionComponent="120"]Tailor your talk

Tailoring your conversation to the individual has never been more important than with contact lens patients. Whether suggesting an update to a satisfied patient, discussing a new payment plan, talking to parents about the benefits of contact lenses for young children or using sport to open a contact lens discussion with the 40-year old male, each conversation is different and can always be improved.

Better communication leads to a better experience for all involved. We all have expectations of ourselves, each other and of our patients, and likewise they of us. Bad experiences are shared so much more quickly and widely than great ones, while good experiences often don’t get shared at all.

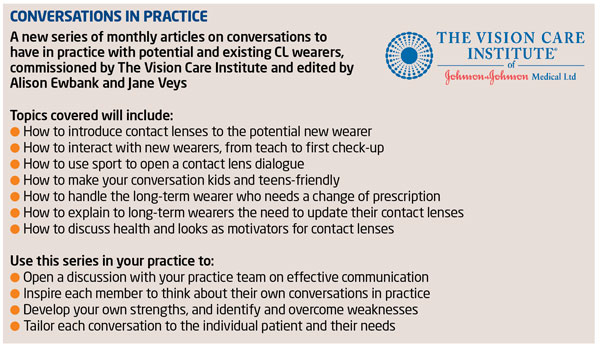

In this series of articles our aim is to provide simple, practical advice and examples to help you enhance your conversations with patients within the practice. We’ll share communication tips from some of the most effective communicators in our profession, and discuss ways of engaging the whole practice team in contact lens conversations. It’s good to talk!

References

1 Schutz W. Profound simplicity. San Diego, CA: Learning Concepts (1982).

2 Fylan F. Communicating confidently. Optician, 2011;242:6319 30-31.

3 Millington A. Patient-centred consultation. Optician, June 13 2008;18-22.

4 Webb H and vom Lehn D. Eye contact and gaze in optometry consultations. Optometry Today, 2011; 51:11 16-18.

5 Webb H, vom Lehn D, Evans B et al. Communication: part 1 – soliciting information from the patient. Optometry Today, 2014; 54:5 52-55.

6 McMonnies CW. Improving patient education and attitudes toward compliance with instructions for contact lens use. Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 2011;34:5 241-8.

7 McMonnies CW. Improving contact lens compliance by explaining the benefits of compliant procedures. Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 2011;34:5 249-52.

8 Morgan S. How can we influence CL wearers to take our advice? Optician, 2013;245:6387 20-24.

Further reading

College of Optometrists, Guidance and Professional Standards. AO4 Patient-practitioner communication.

Millington A. Medical models of consultation. Optician, 2008; Apr 11 30-33.

Millington A. Language of empathy. Optician, 2008; Jun 13 22-24.

Millington A and Court H. Balance of power. Optician, 2009; Aug 14 22-24.

Morgan S. Communication skills: Parts 1-7. Optometry Today, Jul 2011 – Jan 2012.

? Optometrist Clair Bulpin is in independent practice in Gloucestershire, and is an examiner and assessor for the College of Optometrists. Andy Cole is a business coach and leadership development specialist. Both are Faculty members at The Vision Care Institute of Johnson & Johnson Medical