Me and contact lenses go back a long way – 45 years in fact. When I arrived at university in 1972 as a myopic 18-year-old I am not even sure I had heard of contact lenses. I had been wearing glasses since late primary school, having migrated from the back to the front of the classroom until I gradually accepted that I was squinting to see the blackboard.

But I was also sporty, increasingly so at secondary school, playing club football and school rugby regularly. So my curiosity was peaked during my first winter at University of Kent at Canterbury when I saw a notice on campus for a contact lens trial aimed at students.

I went along, had my eyes tested, listened intently at the wonders of the new technologies and signed up. I took to the hard lenses quite quickly and profited from them while playing sport, especially as I had taken up squash since arriving at university.

For the next 20 years or so I just got on with it. Naturally, I lost or broke the odd lens but never really suffered from eye infections or discomfort. However, as the years went by opticians told me I was wearing them too long each day than was good for my eye health.

So eventually when distance RGP lenses became the new norm I swapped to these; better oxygen penetration and so better for the eye. But as my days playing contact sports diminished I wore my lenses less and as I passed deeper into my 40s, I was having to use reading glasses over my distance vision RGP lenses anyway. It was an easy step to take to use varifocal glasses.

But by now soft lenses were increasingly common, the daily disposables the new kid on the block. Family friends and colleagues were switching to them. But not me. I admit partly I was happy with my RGP lens and a new pair online cost me £70. So as long as I did not break or lose one (rare) this was a lot cheaper than my wife’s £30+ a month for her soft lenses daily disposables.

But there was an even more important reason why I did not make the shift. I was repeatedly told by Specsavers and Boots Opticians that ‘my eyes were not suitable’ for soft lenses as I had an astigmatism in my left eye.

On subsequent visits when I enquired about the possibility of multifocal soft contact lenses for my condition I was met with a flat no. It seems that the toric and presbyopic combo made for a difficult customer. Unless the fitting is relatively uncomplicated and standardised the optometrist is not really interested.

And so it is by this circuitous route that I find myself in Leighton Buzzard at the HQ and UK lab of Ultravision being examined by Lynn White, the company’s clinical director. White’s motto is ‘always say “yes” to fitting a soft lens’ and has been trying for some time to get this message across to practices around the country.

She has little time for the idea that specialist eye conditions like mine rule out soft lenses. ‘The technology exists and has for some time’, White says. ‘The problem is that for specialist lenses the chair time for the fitting experience in the practice proves too expensive for their business model.’

State of the art production

But before I sit down with White for my eye MOT and explore my lens options I am given a tour of the company facility, including the lab, by Thomas Hedley from the marketing department.

About 60 people work at the Leighton Buzzard site, explains Hedley. This includes every department – from production, testing, R&D, IT, finance, distribution and sales.

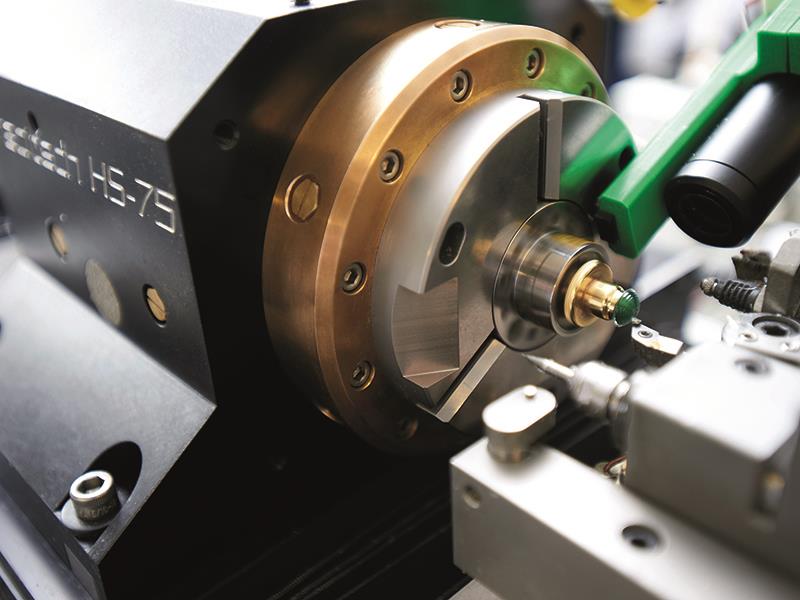

The lab produces both lathed and moulded lenses. The lathed lens is the more traditional method. A pre-programmed diamond drill first cuts the back surface of the lens from a plastic blob after which a second drill cuts the front surface. The lens is then hydrated and, finally, polished and ready for inspection.

I expected the production process to be much more automated than it is. Thomas estimates that each lens passes through the hands of 10 people before it is ready for dispatch.

The moulded lens process is a relatively recent undertaking for Ultravision. The lens starts life as a liquid which is injected into trays of moulds, making it suitable for the mass production of standardised lenses.

Hedley says: ‘You partner a male to the female mould. Liquid is inserted into the gap and it cures, producing the lens. This way we can produce hundreds of identical lenses as opposed to a unique one-off lathed lens.

‘We started doing this about a year ago for hospitals, starting with bandage contact lenses – effectively a plaster for the eye. It’s much cheaper for the hospitals and they can buy it off the shelf. In future we plan to roll out paediatric lenses for babies.’

I was surprised to learn that approximately 50% of the lab’s output is destined for hospitals where there is a huge market for off the shelf emergency, post-surgery and prosthetic lenses.

Whether being packaged in blister packs or vials, the soft lenses are placed in a sterilisation unit for 15 minutes at 115 degrees, after which they are ready to be shipped. Their biggest market outside the UK is the Netherlands but they also have a growing market in the Middle East.

Eye MOT

Back in White’s office-cum-practice area I am ready for my test and fitting. She has used the prescription for my existing RGP distance lenses to make three sets of distance monthly soft lenses, each with a different base curve for my astigmatic left eye. It is easier to start with distance lenses when dealing with specialist fitting since the optometrist does not have to take into account the added complication of different zones for near and distance on a multifocal lenses.

But before we get onto that she realises there is another problem to deal with as she takes topography measurements.

‘Since you have worn RGPs for 43 years, your corneas have been moulded by the rigid material. If you move to soft lenses, there will be a change in corneal shape as your eyes “relax” and you may find your prescription will keep changing,’ I am told.

The problem is particularly acute in my right eye.

‘Soft lenses are quite complicated’, adds White. ‘You need to take a lot of measurements when you have a complicated condition.’

She introduces me to an eye surface profiler, one of only a handful in the country. ‘This measures the whole of the front of the eye rather than just the 8mm or so that a practice will normally do. But if we are doing lens design then we need to measure the whole of the front of the eye,’ White says.

Ultravision has collaborated with Liverpool University on producing the world’s first realistic computer modelling of soft lens and front of the eye. Liverpool helped design the model that programmes tissue strength, density properties and intraocular pressure. Ultravision worked on lens design and tear properties so it can see how the soft lens sits on the eye.

White explains: ‘With a hard lens you put the dye in, put the blue light on and so you see the gap. You can’t do that with the soft lens – the lens sucks up the dye. So what we do is create computer maps where we can see the fit.

‘We create maps where we can see the fitness through the model. We aim to improve fit. Without good fit you don’t get good vision. In this country we have lost the art of working with good fit.

‘The majority of practices only measure a fraction of the diameter of the eye, which gives a little bit of the central shape, but soft lenses are about 14.5mm and nobody has really correlated the full lens and the eye.’

This means that for most practices, when it comes to fitting soft lenses, which flex, they either fit or they do not. It is a bit hit or miss.

The practice of fitting lenses for complicated conditions is something of a lost art, White says. When she worked in a Manchester practice many years ago hospitals contracted out their patient eye care. This meant she got to see very difficult cases routinely: cataract removals, babies born with cataracts, trauma injury cases. But the bulk of this was taken back into the hospitals and practices lost this experience with the result that many optometrists are falling down on fitting for specialist conditions.

White explains that most practices are not set up to deal with patients like me with astigmatism.

‘One of the reasons an optician would have difficulty fitting you with any kind of disposable lens is the axis. It’s not the amount – there are a lot of disposables that would deal with that since yours is not a high power prescription. It’s the fact that it’s oblique, it’s 55 degrees.

‘The majority of the population have a similar horizontal and vertical axis and so that’s what most lens manufacturers make, and they make vanishingly little in oblique range. So even if you get a lens it’s usually compromised on that axis, whereas we can actually do it spot on.’

After putting in the first, flattest, set of distance lens (silicone hydrogen at 74% hydration with a base curve of 6) I do an eye test on the Snellen chart. While I remarked that I could not remember the last time I saw as crisply and clearly Lynn was interested in the fit. ‘The lens is too flat. These are dropping too much, they’re too loose.’

She inserts the second pair with a base curve of 8. ‘These should be a bit more stable, a bit tighter.’

They were but the vision was worse in both eyes to start. It appears the lens on the left eye was a little tight and so the orientation was taking a little while to come around and settle itself. If its 90 degree out it can take a minute to come around.

With the first set the flatter surface is pressing like a rigid hard lens on the front of the eye and so gives good vision but after a while, because it is too flat, it starts to irritate.

All that remains on my first visit is to prescribe the multifocal lens. White tests to see which is my dominant eye. Surprisingly given I am right-handed (most people who are use their right eye for distance) my left eye was dominant even despite my developing cataract.

Nevertheless, she will use right eye for distance and left eye for near because of the cataract.

Three weeks later I returned to Ultravision to have my multifocals fitted. The lens fitted well, stabilising very quickly in the right position in each eye. The vision was excellent, both distant and near, and the ‘compromise’ at both ends of the spectrum seemed, and still do, much less than with my multifocal spectacles.

Naturally, White is happy with the outcome and tells me that getting the monthly multifocal soft lens right is the holy grail for Ultravision and the industry as a whole. Presently, you have to combine a zone for distance (usually middle) with a zone for near vision (usually outer ring), and all fitting within the pupil area. This reduces contrast since the lens is not concentrated at one power. So it is a compromise and it is very difficult to get it right for everyone.

Many optometrists do not supply multifocal lenses but will supply one distance and one near lens. But monovision does not provide the depth perception and is no use really for driving or sports like golf.

The Avanti custom-made lens allows us to change the multifocal zone areas. So we can make the distance zone bigger, use the dominant eye to see for distance and use the other eye for reading and let the brain put it together, says White.

Avanti disposables can be custom made

The challenge is to get the technology right to allow custom-made multifocal lenses at a cost that is commercially viable. With daily disposables that simply is not possible.

Daily lenses by their nature are limited in scope when it comes to fit and power because you are producing 30 lenses a month and this is very expensive if you are making them with very custom-made specifications in base curve, power and so on. It would not be economical to make them for only a few customers.

Monthlies allow you to customise as much as you like because one lens is going to last longer.

The other part of the solution to commercially viable, very customised, specialist lenses lies in the production method itself. The R&D section of the lab at Ultravision is testing out the semi-lathed, semi-moulded lens. Here the back surface is moulded leaving only the front surface to be lathe cut, making the final lens much cheaper. The whole industry is moving in that direction, according to White, but it will be one or two years down the line before such lenses are ready to market.

Despite the success of my multifocals White is not dogmatic about which solution is best for me. ‘There are 20 ways of skinning a cat when it comes to presbyopia,’ she says.

She thinks for my needs – running, driving and minimal computer work, then distance lens with reading glasses might suit me best if I felt I liked the quality of the distance and did not want the compromise that multifocals bring.

I plan to use both sets of lenses in the coming months and see what works for me.

Before I take my leave, White examines my eyes for cataracts. She says it is starting in the right eye and reasonably pronounced now in the left eye. This will increasingly affect my use of the lenses since the lens operates in the area effected by the cataract.

The next stage of my journey will undoubtedly involve surgery at some point. And when that happens it could well involve a date with another of Ultravision’s lenses since they also make intraocular lenses, a sector that White believes will increasingly converge with the contact lens industry.

But that’s another story.