Bill Harvey describes a recent presentation where the vaguest of symptoms were later found to be due to a significant diagnosis

The patient attended for an eye examination on the recommendation of her general practitioner.

The 57-year-old female Caucasian, a heavy smoker, had consulted her doctor regarding an increasing number of dizzy spells, the majority on standing up, but occasionally of sporadic onset. Of more concern were a number of 'mini blackouts' which worried her as she depended on driving for her living.

Of more concern were a number of 'mini blackouts' which worried her as she depended on driving for her living.

Somewhat mysteriously, she was aware that colleagues and friends had noticed and remarked upon some changes in her behaviour - the word 'impetuous' being most memorable.

Eye Examination

The eye examination results were unremarkable. Obviously, accurate fields are essential in such cases and a full Humphrey (central 30-2 and peripheral) were carried out and the results showed good reliability and no loss. Refraction showed the patient near emmetropic for distance with an expected presbyopic addition.

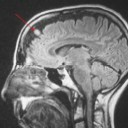

The discs (Figure 1 captured undilated) showed good definition and cupping, so no evidence of any intracranial pressure abnormality. In view of the symptoms, however, she was re-referred to her GP with a full report of the examination. She was subsequently referred on to neurology where she underwent a magnetic resonance interferometry (MRI) scan.

Magnetic Resonance Interferometry

Magnetic resonance interferometry exploits the changes to the body's atoms when subjected to a strong magnetic field.

The patient lies inside a large, cylinder-shaped magnet. Radio waves 10,000 to 30,000 times stronger than the magnetic field of the earth are then sent through the body. This affects the body's atoms, forcing the nuclei into a different position. As they move back into place they send out radio waves of their own. The scanner picks up these signals and a computer turns them into a picture. These pictures are based on the location and strength of the incoming signals. In this way, highly detailed views of the head and its contents are possible.

Sagittal slices (Figure 2), horizontal (Figures 3 and 4) and coronal (parallel to the face) sections allow for a sensitive search through the head for any lesions. Figure 5 shows a small, dense lesion in the falx near the frontal meninges. A diagnosis of falx meningioma was made (arrowed in the close-up).

Meningioma

Meninges are three layers of tissue that cover and protect the brain and spinal cord. From the outermost layer inward they are: the dura mater, arachnoid and pia mater.

In the brain, the dura mater is made up of two layers of whitish, inelastic (not stretchy) film or membrane. The outer layer is called the periosteum. An inner layer, the dura, lines the inside of the entire skull and creates little folds or compartments in which parts of the brain are neatly protected and secured. There are two special folds of the dura in the brain, the falx and the tentorium. The falx separates the right and left half of the brain and the tentorium separates the upper and lower parts of the brain.

A meningioma is a slow-growing tumour of the meninges and most (around 90 per cent) are benign, their effects related to their space occupation. They represent 27 per cent of primary brain tumours and, as such, are the most common. Around a quarter of all meningiomas grow at the falx or parasagitally. They are most common in people between the ages of 40 and 70 and affect women three times more than men.

They can cause seizures and headaches, focal neurological defects (dependent on their location) and occasionally visual loss. Diagnosis is often late due to the vagueness of many of the symptoms (such as carelessness, memory loss, unsteadiness, even 'impetuosity').

The management of such lesions, as in this case, is often to monitor growth of the lesion. As the majority are slow growing, the risk of leaving them is outweighed by any risks of surgery. The proximity of falx meningiomas to major blood supply makes this the best course of action in this case.

Meningiomas growing around the optic nerve cause significant vision loss and eventual blindness so had these symptoms presented with uniocular field loss with no horizontal or vertical respect, as well as olfactory hallucination, an optic nerve meningioma would be a reasonable assumption.

Were growth to represent a worry in future, the lesion may be treated by removal.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Optician Online. Register now to access up to 10 news and opinion articles a month.

Register

Already have an account? Sign in here