The optometric profession has a chance to move forward and play a far greater role in patient care, delegates at the National Optometric Conference in Birmingham were told last week. Changes within NHS primary care, while disruptive, were creating opportunities for individual practitioners and local optometric committees alike.

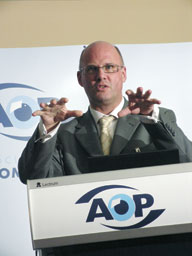

Addressing delegates, Chris Town, acting chief executive for Cambridgeshire Primary Care Trust, explained the rationale behind the changes. Despite increased investment, Town said there were still rising deficits and duplication of effort among PCTs. The 'transformational changes' that the government envisaged had not happened.

Addressing delegates, Chris Town, acting chief executive for Cambridgeshire Primary Care Trust, explained the rationale behind the changes. Despite increased investment, Town said there were still rising deficits and duplication of effort among PCTs. The 'transformational changes' that the government envisaged had not happened.

The far-reaching changes would make PCTs the custodians of the health care budget, and their focus would shift to commissioning health services, rather than providing them. Within the PCTs, practice-based commissioners would be looking to 'buy' community-based services that would prevent hospital admissions. Such changes presented both challenges and opportunities for optometrists, Town said. The biggest challenge, he said, would be making PCTs aware of the role and capabilities of optometrists.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Optician Online. Register now to access up to 10 news and opinion articles a month.

Register

Already have an account? Sign in here