A combination of a headstrong medical student, a physician with some eccentric (and possibly dangerous) ideas and a highly addictive new drug had the potential to be an explosive mixture. Vienna in the last quarter of the 19th century provided the backdrop to experiments with cocaine that were to transform the life of eventual ophthalmologist, Carl Koller, and nearly ruin the reputation of the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud.

The cosmopolitan city of Vienna, the imperial capital of the Austrian Empire was, in the late 1880s, a ferment of ideas ranging across the arts and sciences. News of a new drug with interesting effects, including local anaesthesia, was swirling around. Reports of experiments with cocaine on animals were intriguing but their import was not yet appreciated. One such description runs as follows:

‘A few grains of the substance were thereupon dissolved in a small quantity of distilled water, a large, lively frog was selected from the aquarium and held immobile in a cloth, and now a drop of the solution was trickled into one of the protruding eyes. At intervals of a few seconds the reflex of the cornea was tested by touching the eye with a needle…

‘After about a minute came the great historic moment, I do not hesitate to designate it as such. The frog permitted his cornea to be touched and even injured without a trace of reflex action or attempt to protect himself – whereas the other eye responded with the usual reflex action to the slightest touch.’

Von Anrep, at the University of Würzburg, who published an article on the effects of cocaine in 1880, while noting its numbing effect on the tongue and dilation of the pupil, mused that it might one day be of use in medicine but concluded that, ‘the animal experiments have no practical application; nevertheless I would recommend trying cocaine as a local anaesthetic in persons of melancholy disposition.’ In other words, cocaine might be of use in relieving depression caused by severe chronic pain. This piqued Sigmund Freud’s interest. Freud (1856-1939), was working at the General Hospital in Vienna and was interested in the potential analeptic, or restorative, action of cocaine that von Anrep’s experiments had hinted at. He hoped to help a pathologist friend of his who, after cutting his hand while performing a post-mortem examination, had developed an excruciatingly painful neuroma. His friend subsequently became addicted to morphine and Freud thought that cocaine could be used to cure the dependency. He obtained a supply of cocaine and suggested to a medical colleague who lived on the same floor of his building that they conduct some experiments of their own. Freud’s neighbour was Carl Koller (1857-1944) who, as an intern in the ophthalmology clinic at the University of Vienna, was eyeing a coveted assistant’s post that a piece of original research might gain him; so he was only too keen to oblige.

While Freud experimented on himself to investigate cocaine’s fatigue-suppressing effects and as a treatment for depression and indigestion, Koller noted the numbing effect it had on his tongue and collaborated on a series of animal experiments with Dr Joseph Gartner who was based at another Vienna centre of learning, Stricker’s Institute for Pathological Anatomy. They dissolved a small amount of powdered cocaine in distilled water and instilled it in the conjunctival sac of a frog. They found the frog’s cornea could then be touched without any defensive reflex being elicited. The same results were obtained with a rabbit and a dog. And then, in Koller’s own words:

‘One more step had now to be taken. We trickled the solution under each other’s lifted eyelids, then placed a mirror before us, took pins, and with the head tried to touch the cornea. Almost simultaneously we were able to state jubilantly, “I can’t feel anything.”’

The implication was clear: cocaine had potential for providing local anaesthesia in eye surgery. This would be a huge improvement over the only two options then available, general anaesthesia, which had been discovered around 40 years earlier, and no anaesthesia. The disadvantages of the former were, firstly, that the equipment for anaesthesia then in use was physically cumbersome, which tended to impede surgical access to the eye; and, secondly, the common side-effects of post-operative nausea and vomiting and the consequent rise in pressure in and around the eye would often tear the sutures. The disadvantages of the latter are obvious. Indeed the author, Thomas Hardy, provides a graphic illustration by reporting a local man’s testimony of cataract surgery: ‘It was like a red-hot needle in yer eye whilst he was doing it. But he wasn’t long about it. Oh no. If he had been long I couldn’t ha’ beared it. He wasn’t a minute more than three-quarters of an hour at the outside.’

Armed with his new aqueous solution of cocaine, Koller shortly afterwards performed the first eye surgery, a glaucoma operation, using topical anaesthetic on September 11, 1884. The prestigious Congress of Ophthalmology being just a few days away, Koller quickly wrote up his results in a paper to be presented there. But there was a snag. The meeting was in Heidelberg and the cash-strapped young medic could not afford the train fare. Fortunately, one Dr Brettauer, an ophthalmologist who was visiting Vienna en route, agreed to take Koller’s paper to Congress. News of the new discovery spread quickly around the world. Almost overnight cocaine was being used as a local anaesthetic in all sorts of operations, rapidly becoming a standard procedure – especially once the American doctor, William Halsted, had pioneered local anaesthesia by injection of cocaine.

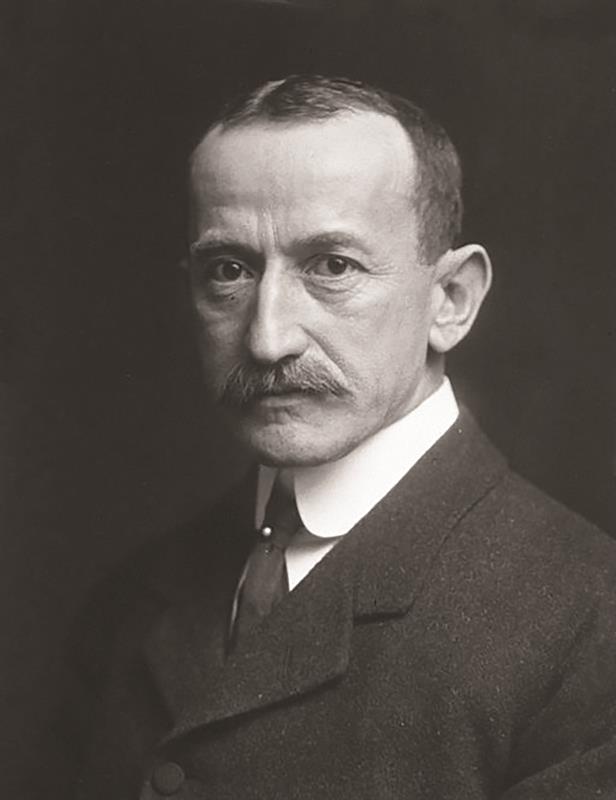

Carl Koller experimented with aqueous cocaine solution

Carl Koller experimented with aqueous cocaine solution

Koller was famous but his future was uncertain. His fiery nature and the ever-present latent antisemitism in Vienna combined to thwart his ambitions there when he got into an argument with a Dr Zinner over the prompt removal of a tourniquet that he believed saved a patient’s injured finger; but the patient being nominally in the other doctor’s care, Zinner called him ‘an impudent Jew’. Admittedly, as Koller’s daughter later said of him, he was ‘a difficult tempestuous young man, one who could never be compelled to speak diplomatically even for his own good’, but you can decide for yourself whether he was justified in slapping Zinner’s face for the insult. The unwritten code of the Patriotic German Student Society, to which they both belonged, dictated that honour must be preserved, Zinner challenged Koller to a duel by sabres the following day. Koller injured his opponent, both men were prosecuted and Koller was later pardoned. But his career in Vienna was over.

Koller felt he had no other option but to emigrate to further his career. In 1885 he moved to the Netherlands to further his ophthalmological training under Herman Snellen. Finding opportunities for advancement limited there, he emigrated again, in 1888, to the United States where he practised successfully for the rest of his life, becoming head of the ophthalmology department at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. He was the first recipient of the Lucien Howe Medal of the American Ophthalmological Society in 1922; and in 1930 received the New York Academy of Medicine Medal.

Sigmund Freud, meanwhile, continued to experiment with cocaine for several years. His efforts to detoxify his pathologist friend, Ernst Fleischl von Marxow, from morphine addiction were a failure; in fact Fleischl became addicted to ever-increasing doses of cocaine too. As the situation became desperate Freud speculated in a letter to his fiancée, Martha Bernays, whether Fleischl (who had been one of Freud’s patrons): ‘He will lend me anything. If so, he may no longer be there when we need to think about paying back.’ A morphine addiction specialist, Albrecht Erlenmeyer, questioned Freud’s results on the use of cocaine for this condition, claiming that not only had patients not given up morphine, they had also developed an addiction to cocaine (as had indeed happened with Fleischl). Erlenmeyer stated presciently that, in addition to alcohol and morphine, Freud had added a ‘third scourge of humanity, cocaine.’

Some commentators believe that Freud was unhappy that his researches concerning cocaine were overshadowed by Koller’s discovery of local anaesthesia for eye surgery. Others point to correspondence between the two friends, which maintain a friendly tone. But Freud is also quoted thus: ‘The cocaine business has indeed brought me much honour, but the lion’s share to others.’ A case for psychoanalysis, perhaps.