Ultra-widefield imaging is increasing in popularity in routine optometric practice. The many reasons for this are diverse, but broadly fall into a number of groups. These are:

- Covid-19 related;

- Ease of remote imaging as a result of Covid-19

- Ease of review of images with social distancing from patient

- Ease of transfer of data to third party clinician

- Ease of use;

- In most cases, dilation is not necessary

- Quick to obtain images

- Non-invasive for patient

- Painless

- Clinical benefits;

- Rapid to use

- Wider area of retina viewed routinely

- Retina viewed at different depths

- Autofluorescent (functionality) images available

- Comparison modules available

The following case study demonstrates many of these benefits and demonstrates why it is essential to view the peripheral retina in all cases at all visits and how scanning laser ophthalmoscopy assist diagnosis of pigmented lesions.

Choroidal Naevus

A choroidal naevus is a very common finding in an otherwise normal healthy retina, present in about 1 in 20 of the general population.1 With the advent of ultra-widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy systems, such as Optomap, the presence of naevi has been greatly highlighted and it is not uncommon to see upwards of 80 naevi a week in a routine cohort of patients. Fortunately, the risk of a naevus converting over time to a choroidal melanoma is slight, fewer than 1 in 8,845 according to some estimates.2 However, this means that all naevi do, to some extent, pose a risk. It is, therefore, very important to be aware of their presence at all times. It is also important to have the means by which any progression can be looked for and monitored over time.

In this case study, we consider an image captured of the retina of a three-year-old white male. The young patient was totally asymptomatic on presentation, with no remarkable history and no family history of note. His visual development appeared normal and his mother had brought him along for a routine first eye test to establish a baseline for future examinations.

All elements of the test appeared normal, confirming good acuity and good binocular development. Direct ophthalmoscopy, not easy to perform due to the active nature of the child, showed no abnormality in either eye while a Volk lens examination was not possible as cooperation was limited.

The child was, however, highly receptive to the concept of having his eyes imaged and so we turned the act of imaging into a game, resulting in good cooperation and an excellent retinal image as a result.

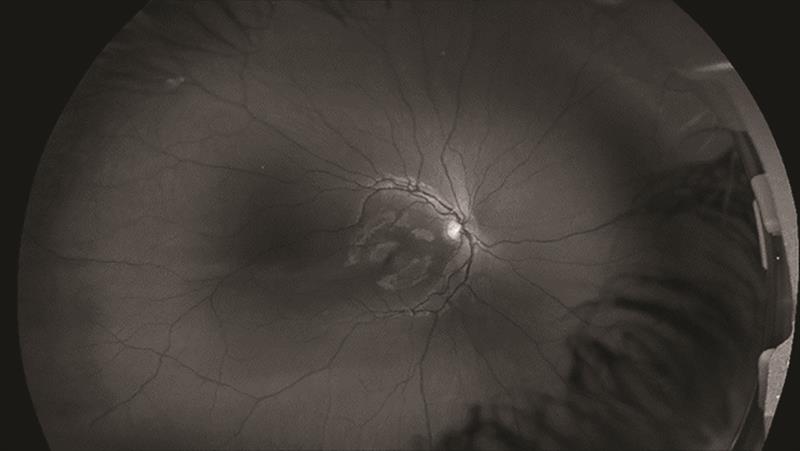

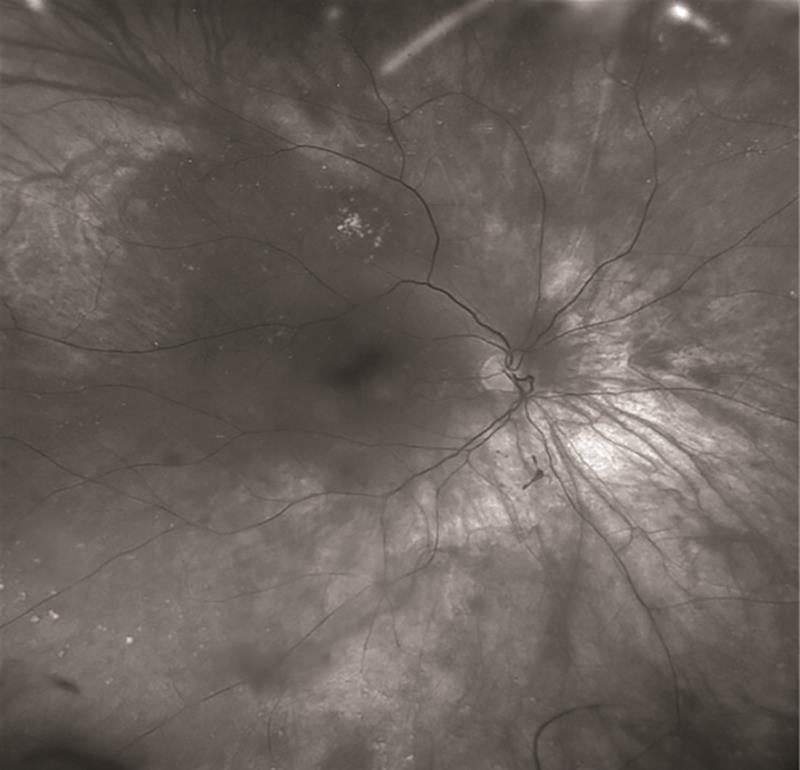

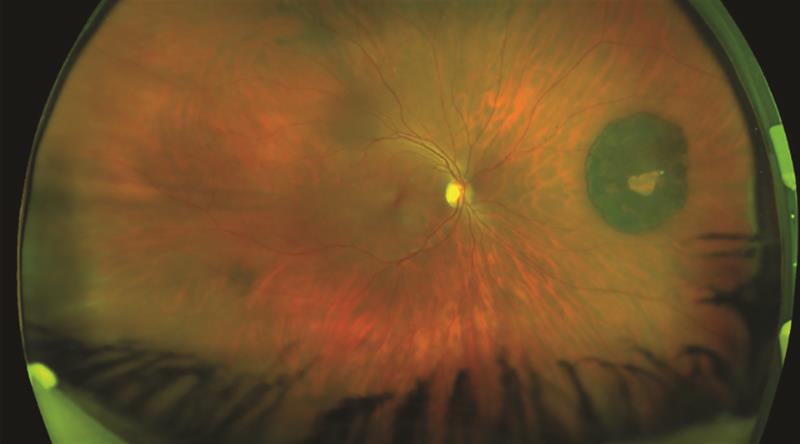

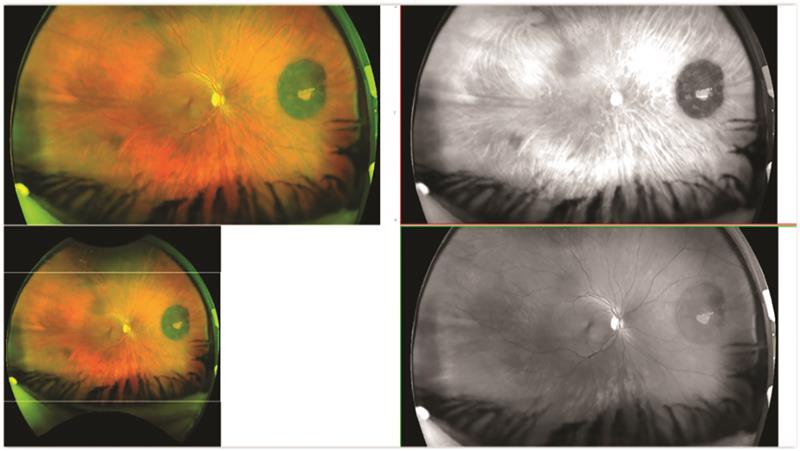

Figure 1 shows the colour image obtained for the right eye, revealing a large, pigmented lesion nasal to the optic nerve head. Figure 2 shows the green channel selected images of the same view, revealing the lesion is not seen at the retinal surface level. Figure 3 shows the red channel image, where the clear view of the lesion suggests its location to be deeper, at the choroidal/RPE interface level.

Figure 2: Image of the retinal surface (green channel)

Figure 2: Image of the retinal surface (green channel)

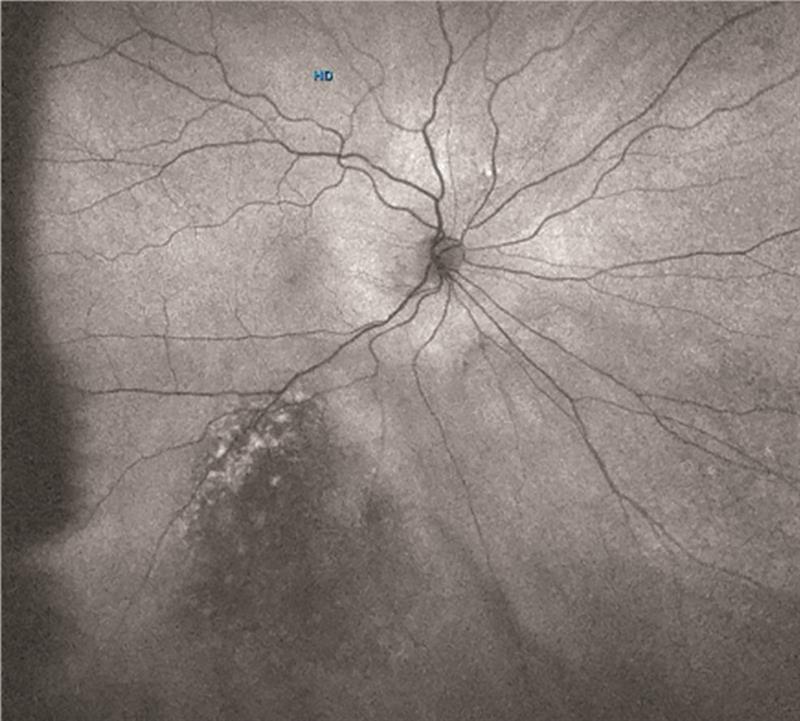

Figure 3: Image of deeper retinal levels (red channel)

Figure 3: Image of deeper retinal levels (red channel)

This confirmation of the pigmented lesion as residing at the deeper level while absent from the retinal surface level immediately aids with the diagnosis and helps to differentiate from retinal pigmentary disturbances, such as CHRPEs (congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium) as will be discussed later.

Discussion

With all lesions of this type, it is important to establish their status and then act accordingly. The immediate question to be asked has to be whether this dark lesion is benign, and so unlikely to impact on other tissue, or has the potential to become malignant. Ultimately, this decision will influence whether the lesion needs to be referred or not. While the decision made at this stage is very important whoever the patient, in a very young patient, with a long life ahead of them, it is even more critical.

The Optomap diagnostic software (Optos Advance) offers several tools to be utilised to aid in diagnosis. The first thing to do here is to establish whether the lesion is flat or raised. In this case, magnifying the image greatly facilitates analysis of the course of the retinal surface blood vessels as they traverse the lesion. The magnified images for this patient clearly showed there was no sign of vessel deviation and hence the lesion is very likely to be flat.

Secondly, analysing the images as seen in the two different channels shows that the lesion is clearly observed at the deeper level but is not seen at the retinal surface. This suggests the lesion is at choroidal level and does not invade higher levels. This also, again, suggests it is flat. This type of imaging is highly characteristic of a benign choroidal naevus. The fact that the lesion is not seen with the green channel may well explain why many optometrists see so few naevi in a normal cohort of patients using standard fundoscopy means. Hence, it may well only be when a naevus has altered and become malignant that they may see the resultant lesion. This transformation, of course, occurs much later and is potentially life-threatening to the patient. Establishing the presence of this lesion at a young age is vitally important.

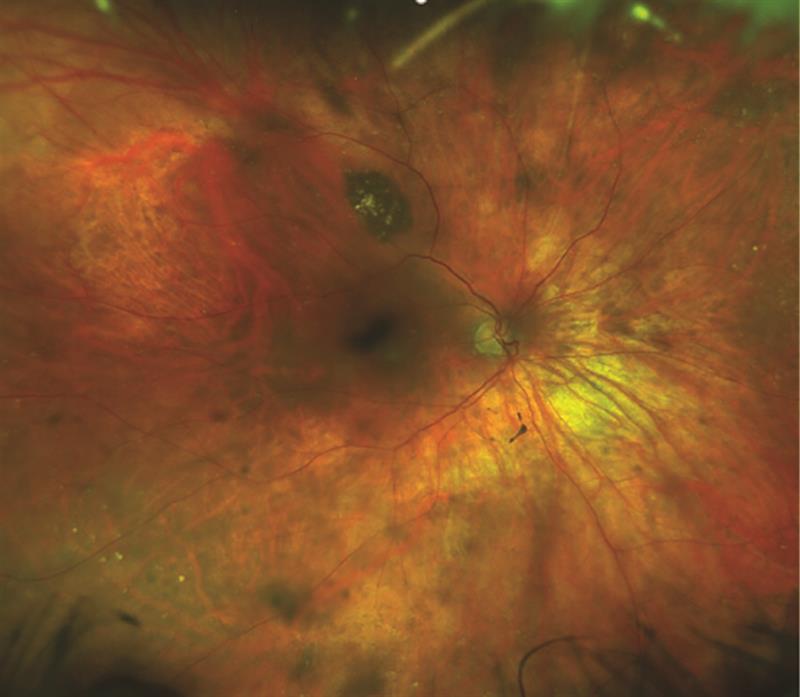

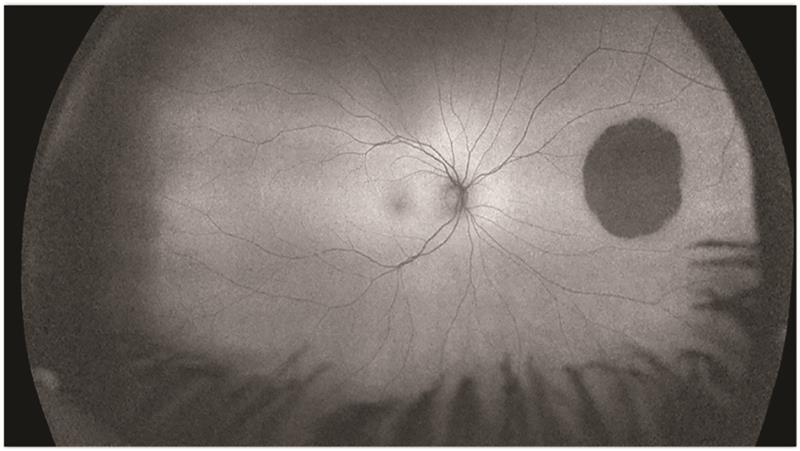

While not used on this particular patient, fundus

autofluorescence (FAF) imaging provides an excellent adjunct to diagnosis. If there is lipofuscin present on the retinal surface, as shown by hyperfluorescence on the retinal surface, then this is much more likely to indicate a malignancy requiring urgent referral to an oncologist for action and treatment (figure 4). The absence of any hyperfluorescent areas over a pigmented lesion would tend to suggest normal metabolic activity lending strength to the diagnosis of naevus.

Figure 4: Autofluorescent image of an amelanotic melanoma, showing the presence of lipofuscin on the retinal surface as areas of hyperfluorescence

Figure 4: Autofluorescent image of an amelanotic melanoma, showing the presence of lipofuscin on the retinal surface as areas of hyperfluorescence

With a child of this age, the debate as to whether to refer or not is always a reasonable one. It is not good practice to load up busy secondary care clinics with patients who do not need to be there. But then again, is it good practice to leave one so young without a second opinion about a lesion with even the tiniest chance of it becoming a concern?

In this case, given the results already discussed, it was decided it would be safe at this stage not to refer and instead to regularly monitor the patient. I would always give the parents a copy of the images on a memory stick in case they were to move away from my area, in which case their next optometrist would have the relevant data to hand. I would also inform the eye clinic of my findings with copies of all images, sent electronically via a secure network. This way, the clinic has the opportunity to intervene if they wish, or to allow you to continue to monitor. I would then arrange a set schedule of timings to reimage the child over time. Once again, the Optos Advance software has a system known as ‘comparison overlay,’ by which successive images can be overlain. Then, by scrolling up and down through the images, changes can be observed very easily when occurring. It should, of course, be remembered that lesions such as this in a young child are highly likely to increase in size over formative years quite normally in line with growth of the child. So, lesions changing in size in young patients may well not be of concern. In adults, changes in the size of a pigmented lesion would be regarded as highly suspicious.

The presence of drusen overlying a naevus is not an uncommon finding and represents where a naevus has been present for a long time. This suggests an element of chronicity and is actually a positive indicator for the clinician, suggesting that transformation is unlikely to be occurring. Often, because a naevus has not previously been seen with standard fundoscopy, the presence of a random clump of drusen can cause confusion. However, this can be readily explained as shown in figures 5 to 7.

Figure 5: Naevus with overlying drusen

Figure 5: Naevus with overlying drusen

Figure 6: Naevus clearly visible in the red channel with overlying drusen

Figure 6: Naevus clearly visible in the red channel with overlying drusen

Figure 7: Naevus apparently absent in green channel with only drusen present

Figure 7: Naevus apparently absent in green channel with only drusen present

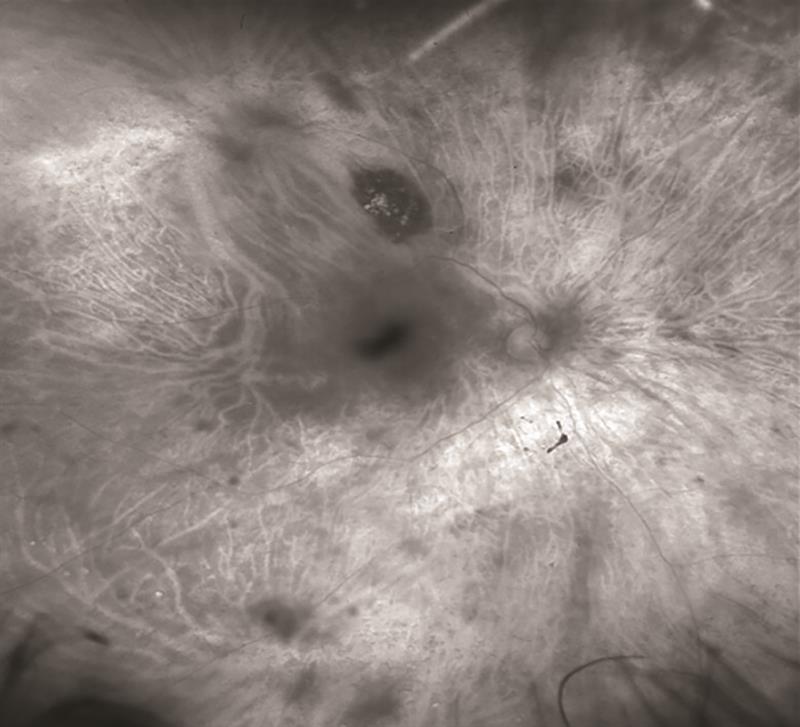

Another common dark lesion that can cause confusion is a benign congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (better known as a CHRPE, usually pronounced as ‘chirpy’). The clue as to significance of this lesion is held within the first two words; namely ‘congenital’ and ‘benign.’ These do not present a problem, and on an Optomap image will appear dark on the colour image (figure 8) and will also be present on both the red and the green channels (figure 9). Possibly the most significant aid to diagnosis with CHRPE is the autofluorescent image. This will always appear totally dark across the whole of the lesion, as there is no functionality within the RPE in this area and hence no lipofuscin production with the RPE. Some CHRPEs, as they age, will develop depigmented lacunae, and may depigment almost across their entirety. This can cause confusion when diagnosing, but the autofluorescent image for the area will not change, despite changes to the pigmentation, and will remain totally dark (figure 10). Hence, the reason why fundus autofluorescence is such an important diagnostic tool.

Figure 8: Colour image of CHRPE with central depigmented lacuna

Figure 8: Colour image of CHRPE with central depigmented lacuna

Figure 9: Composite image showing CHRPE visible on both red and green channels both showing depigmented lacuna

Figure 9: Composite image showing CHRPE visible on both red and green channels both showing depigmented lacuna

Figure 10: Autofluorescent image of CHRPE showing total dark area including region of lacuna

Figure 10: Autofluorescent image of CHRPE showing total dark area including region of lacuna

Summary

While choroidal melanoma is a rare finding for optometrists, the presence of naevi within the retina should never be ignored. There is always a remote possibility that a naevus may transform over time to a malignant state. It is, therefore, very important to monitor all choroidal naevi for change over time, especially when detected in young or more vulnerable groups. The ability to recognise the presence of naevi is, therefore, vital in routine eye examinations. Choroidal naevi are known to be common and therefore not seeing them on a regular basis should be a cause for clinical reflection. The College of Optometrists, within its clinical management guidelines, has produced a useful synopsis on pigmented fundus lesions.3

Simon Browning is an independent optometrist who ran his own practice for many years until two years ago when his practice became a part of the Hakim Group. He has used ultra-widefield imaging devices for over 20 years and now dedicates much of his time to his new role as an educator specialising in delivering training to practices and individual optometrists specifically associated with the Optos family of instruments. He has delivered lectures and training throughout the UK, and in Europe the USA and Australia. He has developed a suite of interactive training materials, all GOC CET approved, to develop knowledge, confidence and ability around the use of ultra-widefield and autofluorescent retinal imaging.

References

- Chien JL, Sioufi K, Surakiatchanukul T, Shields JA, Shields CL. Choroidal nevus: a review of prevalence, features, genetics, risks, and outcomes. Current Opinions in Ophthalmology. 2017, May;28(3):228-237

- Singh AD, Kalyani P, Topham A. Estimating the risk of malignant transformation of a choroidal nevus. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1784-1789

- www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/clinical-man...