As eye care professionals (ECPs), we are used to identifying eye conditions and making onward referrals if a person’s eye condition cannot be treated in the community. But do we stop and think about the impact on a patient when we identify a problem during an eye examination?

How does a patient respond to a diagnosis or to uncertainty about a diagnosis? What are their immediate thoughts when the ECP shares their findings? If a patient is told that their sight cannot be fully restored, how does that make them feel?

What is the impact of sight loss on their everyday function, their emotional wellbeing and their social interactions? What is the impact of good communication throughout a person’s sight loss journey and what can we do as ECPs to support our patients? These questions will now be considered.

Support at the point of diagnosis

When an ECP identifies a problem with a patient’s vision, this can be a very anxious time for the patient. Some patients immediately think about the worst-case scenario; they might be reminded of a friend or relative who lost their sight and worry that the same could happen to them.

At this point, it is important to create a supportive environment for the patient, whereby the practitioner gathers and provides information,responding sensitively to the patient’s emotions.1 Transparency about the diagnosis and discussing the reason for further investigations, as well as shared decision-making, contribute to better outcomes and improved patient satisfaction.2,3

ECPs can ensure that patients receive their diagnosis in a supportive environment, whereby patients are signposted to relevant sources of information and local support.

Emotional impact of sight loss

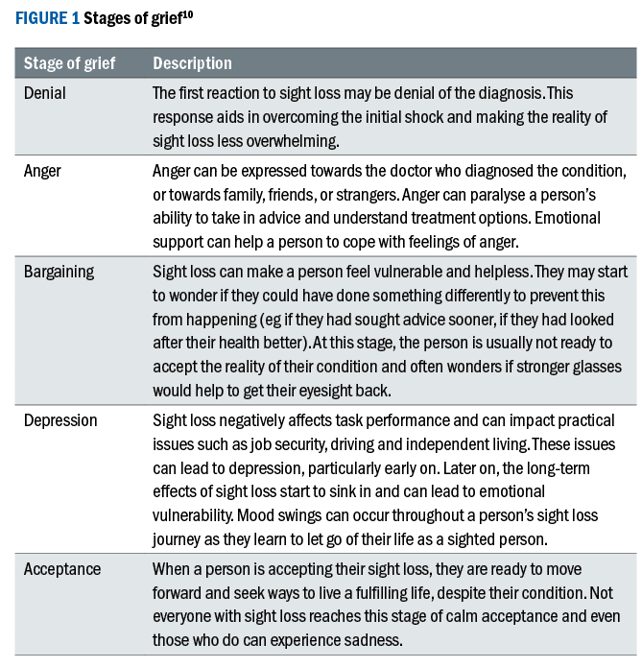

It is common for patients with visual impairment to experience low mood, anxiety, depression and reduced quality of life.4-8 For those who lost their eyesight later in life, the response is often akin to bereavement, whereby patients experience some or all stages of grief, namely denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance (see figure 1). Fear of sight loss and feeling isolated are also common reactions.9

In the first two years after visual loss patients often experience greater denial and lower acceptance than at a later stage. As a result, people are more likely to engage with strategies and rehabilitation when they have made progress in accepting their vision impairment.11

Nevertheless, low mood and depression can be experienced at any time in a person’s sight loss journey.12 Studies have shown that depressive symptoms are common (up to 43%) among patients attending low vision services and that many patients do not receive treatment or support for these symptoms.13,14

A small proportion of patients with depression, who are otherwise psychologically healthy, go on to develop suicidal thoughts. This is especially true for patients who experience fear of going blind. Patients with total blindness tend to accept their new social role and are more likely to engage in rehabilitation.15

For patients to engage in rehabilitation and wellbeing programs, they need to be made aware of these services and the services need to be accessible.16 Health care professionals play an important role in raising awareness and therefore training is recommended to address any lack of knowledge, skills and attitude and to enhance clinician-patient communication on mental health.17

The role of eye care professionals

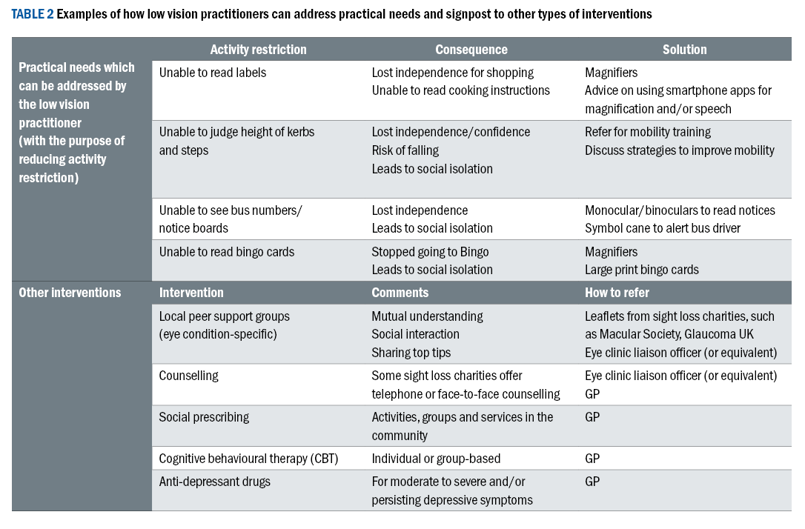

Visual impairment typically affects a person’s ability to perform tasks, which in turn leads to activity restriction and potentially to reduced participation in society. Reduced social participation is a contributing factor for depression in adults with visual impairment.18 Low vision practitioners are well placed to manage patients’ practical needs and to signpost patients to other types of interventions (see table 2).

Depression screening

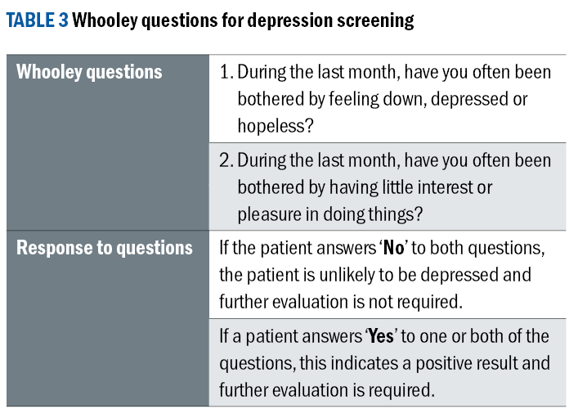

In the author’s experience, it is helpful to create a relationship of trust and to normalise emotional responses to sight loss before introducing questions to formally screen for depression. Fenwick et al19 explored how depression can be identified and managed in an eye care hospital and realised that clear guidelines about clinicians’ responsibilities and referral pathways could improve patient outcomes.

NICE guidelines20 recommend using the Whooley questions21 for depression screening (see table 3). The questions are designed for adults who are at risk of depression due to a chronic physical health issue. If a patient screens positive, they are usually referred to their GP. At the same time, support can be sought from sight loss charities and local support groups.

Perspectives from people living with sight loss

Each person has a unique response to sight loss and as low vision practitioners we can learn from listening to our patients. This section contains three stories from people living with sight loss. The first two ladies met each other at their local support group from the Macular Society.

They have been working closely together with the author to raise awareness of the Macular Society within the local hospital eye service (HES). The third person works as a patient support officer (equivalent to eye clinic liaison officer) at the HES, where she offers support for people with sight impairment.

Case 1

Cleodie was diagnosed with macular degeneration about 20 years ago and experienced gradual sight loss over this time period with episodes of sudden deteriorations at the start and at other points throughout her journey. She is now seeing very little, but has ‘just enough peripheral vision to walk around safely’.

Cleodie first noticed that there was something wrong with her eyesight when she saw the letters on shop windows double and when actors in the theatre appeared to have long thin faces. She immediately arranged to see her optometrist and was referred to the HES on the same day.

A week later she was told that treatment was likely to cause more harm than good, but that she would not go blind. Anti-VEGF treatment was not yet available. Information provision was very minimal:

'No one said there was a Macular Society. Nobody said that there would be help at the RNIB. I could have done with getting a leaflet.'

Her son did a Google search on macular disease and discovered the Macular Society. Two friends from church who were members of the Macular Society tried to get her along to their meetings. Her initial response was that she did not need this, because she could still see alright, but eventually, she ended up giving her friend a lift to the meeting as she was still able to drive.

Afterwards, she got in touch with some of the organisations who were presenting at the meeting, and she to attend the meetings with the Macular Society:

'At one of the meetings a person from the library came and wanted to start an audio book group and asked for support. This audio book group became a support group. After the book discussion, we would chat to each other about our everyday life. The big macular

meeting was not really a support group. The smaller groups were better for talking about our problems. That was emotional support for me. There were other people who were prepared to talk about it.'

It was only six months after initial diagnosis that Cleodie had to give up driving:

'Having to give up driving was not good. I felt upset. It took away

some of my freedom. Luckily, I live in a place with good public

transport. But my roots are up in the Highlands and it became

very difficult to get there now. As a result, I cannot see

my family as much as before.'

Cleodie shares about other times when her vision suddenly deteriorated:

'At some point I went to Venice with a friend. Before I went,

I visited a local art exhibition and I could see the paintings

quite well. When I went to Venice to see some favourite

paintings, I could not see any of the detail. I sat down

and wept. That had happened very suddenly.'

Cleodie explains that you must constantly adapt to your sight loss and do things differently. She explains how sight loss affected her emotional well-being:

‘It’s just like bereavement. I started off with denial. “I don’t belong to these people.” Then I started being anxious. Mostly it went quite slowly. I was diagnosed in January and by the autumn I had to give up driving. That was quite a stage really. More lately, my sight has deteriorated quite a lot. I’ve found that quite upsetting. With a gradual loss, you adapt to the way it is, but then it gets worse, and you have to adapt all over again. Big steps are more challenging. You realise that what you could read a few days ago, you cannot read now. I’m having difficulties pouring things out, I knock things over, I break things and that’s infuriating. In the early stages, I found myself using quite a lot of strong language and I’m now using strong language again. I’ve had a more difficult time in the past few months. It’s not going to get any easier.’

The Macular Society and the friendships that were formed at the local macular support groups have been a lifeline for Cleodie and she feels that support groups are the best form of emotional support for her. Finally, when I asked her for some advice for optometrists, Cleodie said:

‘Optometrists and eye departments should send information and appointment letters out in large print.’

Case 2

At a routine sight test 24 years ago, Jean was told that she had the early stages of macular degeneration. It was not until 10 years later that she was diagnosed with wet macular degeneration. Jean shares her experience:

‘The optometrist said: “I’m sorry to say, but there is no treatment. You will probably be blind by the age of 80.” This was 24 years ago and I’m in my late 80s now. She gave me dietary advice. Ten years later, I started to see vertical lines ‘dancing’ and my friend urged me to see my optician. I was seen the same day and shortly after, I started my anti-VEGF treatment. My optician advised me to take vitamin supplements and I feel that these have kept my eyesight going.’

Jean explains how her vision affects her in her daily life:

‘I can see quite well. I have difficulties with writing, because I can’t see the tip of my pen. I can’t see what I’ve written. I find the clarity of print almost more important than the size of the print. With the right lighting I can still read and do my jigsaw puzzles. I use talking books. I used to do eccentric viewing training, which taught me that sometimes, I’ve got to look at things from a different angle.

Outside, I carry a stick because I can’t see the edge of pavements. The speed at which cars are coming…I have to stand for a little while. I’m not depressed, but frustrated. I can no longer sew the bottom of my trousers, because I can’t see the needle and the black thread.'

The Macular Society has been an important source of information and peer support and she may not have found out about it if she had not met the local group leader during a holiday. She explains that it is difficult to find information about the Macular Society and other available support for people with sight loss as the eye care liaison officer (ECLO) service is tucked away in the HES and information is not routinely handed out to patients.

Jean’s final piece of advice for ECPs is that it would be good if opticians and eye departments could familiarise themselves with local support groups and raise awareness about these. For patients with AMD she recommends to go along to support groups and information centres while they can still see, rather than wait until the vision is gone.

Case 3

Seven years ago, Jo attended her optometrist with a five-day history of ‘spots in front of her eye’. The consultant at the HES on that same day thought she presented with the first stages of multiple sclerosis and arranged for a six weeks follow-up. Jo remembers how she felt:

‘This was a massive shock for me. I was thinking ‘wheelchair, wheelchair’. I was in tears at that consultation, where she misdiagnosed. She should never have said that. I was given a box of tissues and was advised to go home.’

Her vision deteriorated rapidly and within 10 days her vision in the right eye reached the stage it is at now. She is able to see bright colours and contours and she can read large print. However, she relies on speech technology for most things.

At the time, she was told by the neuro-ophthalmologist that her other eye would not be affected. However, there was no clear diagnosis at that point. She continued to live a near-normal life:

‘I just lived with this hazy eye with blocked out vision for about six months. I was not that worried. I thought: “one eye is not working,

I’ll just carry on.” I was working full-time at that point and I couldn’t understand why I was so drained and fatigued. People would come up to my right hand side and I would suddenly notice them. I got a shock when they appeared. So I said, “please come over to my left,” and I realised my right eye really was not working. I had no support from anybody. Looking back now, I should have had support from somebody who is understanding of the situation, who could point me in the direction of other support services, peer support, just to know that this is not so rare. But on the flip side of that I was managing pretty well, apart from the fatigue. I still didn’t have a diagnosis... It didn’t register until the second eye went six months later.’

Jo presented to the HES with the same symptoms as with her first eye and was kept in hospital for four days. She had many tests and high dose steroid treatment to ‘try to save the eye’. Eventually, she was given the diagnosis of non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION).

‘On day one, it hit me that my sight might actually deteriorate and that I might lose as much in the second eye as in the first. It was late at night and I was in the ward. Everyone had gone home. I was given so may steroids I could not sleep. At about 11 o’clock at night I was in tears and actually got out of my bed and went up to the desk and said: “Is there anyone that I can talk to?” The nurse could see I was upset and she said: “We have a service upstairs, the RNIB, and they can come down and speak to you in the morning.” So that’s what happened. The first day of support. My vision dropped over the next 10 days. I was discharged on day five and the ECLO helped me thereafter.’

‘After being discharged from the hospital we went on a weekend break to Perthshire with the family. I realised I couldn’t see in the dark, I couldn’t walk properly in the woods and I had to keep to the tarmac. I walked really slowly, my balance was all lost. It was just such a weird experience. I felt I was floating really. I wasn’t stable in any way. I couldn’t really do things for myself. When I came home, I was signed off work, in fact, I was signed off for a year and then left. But ultimately my employer was not helpful at all and I had a lot of stress. Everything had been taken out of my hands. We were financially stuck. I couldn’t do the shopping any more, so my husband had to take up the food shopping. I couldn’t see the TV and that stressed me. I was considering all my losses: I will never be able to go camping again, I’ll never be able to drive… I used to dream about driving. It’s a really hard loss.’

Jo’s sight loss did not only affect her work and independence, it also affected her relationships with her husband and her two daughters, aged 12 and nine:

‘My husband was terrified I would lose all my eyesight altogether. He was very emotionally scarred by it all. It took a long time for my husband to adapt. There was a lot of difficulty in our relationship. The ‘Sighted Guiding’ course was good. My husband learned how to help me cross the road by offering his elbow, rather than dragging me. My younger one got it. I would ask her to read the back of packaging. We used to read to her at that point and we just turned it around. She said: “Mummy, why don’t I just read to you.” So her reading is brilliant now. She is reading to me and that is the bed-time story. She was totally great. We’d go to bus stops and she would read the timetable on the bus stop and tell me when the next bus was coming, so that helped her grow up a bit.’

Jo sought support from a counsellor who encouraged her to go out and stay active. Nevertheless, she did experience loneliness and felt that her ‘identity chipped away’. She describes her emotional response to sight loss:

‘I think I was upset because my husband was so upset. I was obviously angry. But what was the first thing… I was so sad. Well, I went through the grief cycle: Sadness, anger, frustration, really frustration was the first thing. I remember the ECLO saying to me ‘what you’re experiencing is normal when you’re going through this’ and that was such a relief. I burst into tears and I thought: “I’m not alone.” I can’t really remember at what point in that first year I did what, but the RNIB ran a sight loss course. I also volunteered there to try and get back into working in an office. I think that was year 2. I didn’t work for 2 years. But I pushed myself to walk to the beach every day. I’ve heard from many people who had suddenly lost their sight that they stay inside all the time because they cannot do

anything. I thought: “I can’t go like that.”

The first two years after she lost her vision were very difficult, but she reached a turning point when she had decided to leave her job after one year:

‘I felt so relieved, because I got all my holiday pay and a lump sum of money, so I was able to buy a MacBook and learn how to use it.

I started to turn things around and do more things for myself. I went to an organisation called ‘Into Work’, who help disabled people to find a work place and they were brilliant. They helped me find my current job. I had structure. So that was probably the turning point when I was able to do more things for myself and think about looking for a job. I wanted to be able to go into work and I wanted to do a training course at the Apple store. Then I volunteered at the RNIB. So I was kept really busy. I felt I had some purpose and I wasn’t ill any more. The first wee while I was on steroids and had to have injections. Once this was over I didn’t have to lie on the sofa all the time, feeling exhausted. The hallucinations had gone. I felt better in myself. I am not the same person as I was before this happened. My life was going in one direction and now it’s going in the other direction, so it’s completely different. It’s not to say it’s any worse: it’s

different. It’s great, because I do the job I do, I picked up my singing more, I do things differently, I’m helping others.’

Jo’s advice for ECPs is to be careful about how information is passed on, especially to younger people who are not used to having eye or health problems and are suddenly confronted with sight loss.

Conclusion

This article shows that every person responds differently when they experience visual loss. ECPs have the opportunity to support patients throughout their sight loss journey. Sharing the diagnosis can be done sensitively to help patients with the initial emotional response at this time.

Signposting to sight loss charities and support groups help patients for information gathering and peer support and referral to low vision services can aid people with their practical needs. Depression screening is particularly recommended in a low vision setting.

- Cirta Tooth works as a specialist low vision optometrist in the hospital eye service as well as in private practice and has just completed a Master’s in clinical optometry at Cardiff University. She enjoys supporting adults and children with visual impairment through teaching, research, raising awareness and involvement in the local community.

References

- King, A and Hoppe, RB. Best-practice for patient-centred communication: A narrative review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2013;5(3):385-393. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00072.1.

- Berger, ZD et al. Patient centred diagnosis: Sharing diagnostic decisions with patients in clinical practice. British Medical Journal. 2017;359. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4218.

- Dahm, MR and Crock, C. Understanding and communicating uncertainty in achieving diagnostic excellence. Journal of American Medical Association. 2022;327(12): 1127-1128. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.2141.

- Choi, HG, Lee, MJ and Lee, S-M. Visual impairment and risk of depression: A longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(2083). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20374-5.

- Court, H, McLean, G, Guthrie, B, Mercer, SW and Smith, DJ. Visual impairment is associated with physical and mental co-morbidities in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medicine. 2014;12(181). doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0181-7.

- Crewe, JM, Morlet, N, Morgan, WH, Spilsbury, K, Mukhtar, A, Clark, A, Ng, JQ, Crowley, M and Semmens, JB. Quality of life of the most severely vision-impaired. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2011; 29: 336-343. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02466.x.

- Finger, RP, Fenwick, E, Marella, M, Dirani, M, Holz, FG, Chiang, PP-C. And Lamoureux, EL. The impact of vision impairment on vision-specific quality of life in Germany. Investigative Ophthalmology and Vision Science. 2011;52(6):3613-3619. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-7127.

- van der Aa, HPA, Comijs, HC, Penninx, BWJH, van Rens, GHMB and van Nispen, RMA. Major depressive and anxiety disorders in visually impaired older adults. Investigative Ophthalmology and Vision Science. 2015;56: 849-856. doi:10.1167/ iovs.14-15848.

- Macular Society. Emotional impact of sight loss. Available at: https://www.macularsociety.org/media/2rxhckfy/emotional-impact-ms021-2021.pdf [Accessed 8th February 2024].

- RNIB (Royal National Institute of Blind People). Good mental health: the five stages of grief. Available at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/your-eyes/navigating-sight-loss/resources-for-mental-wellbeing/guides-to-good-mental-health/good-mental-health-sight-loss-five-stages-grief/ [Accessed 8th February 2024].

- Pollard, TL, Simpson, JA, Lamoureux, EL and Keeffe, JE. Barriers to accessing low vision services. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2003;23: 321–327.

- Bergeron, CM. Psychological adaptation to visual impairment: The traditional grief process revised. British Journal of Vision Impairment. 2013;31(1): 20-31. doi:10.1177/0264619612469371.

- Evans, JR, Fletcher, AE, Wormald, RPL. Depression and anxiety in visually impaired older people. Ophthalmology. 2007;114: 283-288. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.006.

- Nollett, CL et al. High Prevalence of Untreated Depression in Patients Accessing Low-Vision Services. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(2): 440-441. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.009.

- de Leo, D, Hickey, PA, Meneghel, G and Cantor, CH. Blindness, fear of sight loss and suicide. Psychosomatics. 1999:40(4): 339-344.

- Dillon, L, Tang, D, Liew, G, Hackett, M, Craig, A, Gopinath, B and Keay, L. Facilitators and barriers to participation in mental well-being programs by older Australians with vision impairment: community and stakeholder perspectives. Eye. 2020;34: 1287-1295. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-0992-z.

- van Munster, EPJ van der Aa, HPA, Verstraten, P and van Nispen, RMA. Barriers and facilitators to recognize and discuss depression and anxiety by adults with vision impairment or blindness: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06682-z.

- He, W, Li, P, Gao, Y, You, J, Chang, J, Qu, X and Zhang, W. Self-reported visual impairment and depression of middle-aged and older adults: The chain-mediating effects of internet use and social participation. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.957586.

- Fenwick, EK, Lamoureux, EL, Keeffe, JE, Mellor, D and Rees, G. Detection and management of depression in patients with vision impairment. Optometry and Vision Science. 2009;86(8): 948-954. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181b2f599.

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: Recognition and management. 2009. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91 [Accessed 8th February 2024].

- Whooley, MA, Avins, AL, Miranda, J and Browner, WS. Case finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12: 439-445.