Dr Ilse Daly delves into the incredibly acute vision of the eagle

When it comes to vision, eagles are widely considered to be at the pinnacle of visual evolution. And this reputation is well-earned; that they can spot their prey from distances that would have us reaching for the binoculars strongly implies the acuity (the ability to resolve fine detail) of their eyes far exceeds our own. Indeed, in comparable experiments, eagles are able to discriminate detail that is almost twice as fine as the finest detail that we can see. So what is it about eagle eyes that make them so keen?

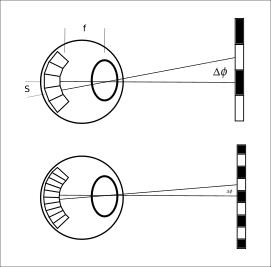

There are two ways an animal can increase the resolution of its eye; they can reduce the space (see figure 1) between their photoreceptors (cones and rods) and they can increase their eye size. Due to the physics of light, the absolute minimum separation between cones for an eye to function correctly is 2µm (0.002mm).

Figure 1: Eagles increase the resolution of their eyes by reducing the space between their photo-receptors (cones and rods).

Figure 1: Eagles increase the resolution of their eyes by reducing the space between their photo-receptors (cones and rods).

f is the focal length.

s is the spacing between photoreceptors.

∆θ is the minimum resolvable angle.

As s, the spacing between photoreceptors, decreases, so does the minimum size of the detail (as shown by the black and white grating) that can be discriminated by an eye.

Intuitively, having smaller photoreceptors should also benefit the animal as more could be packed into the same area of retina. However, photoreceptors, and therefore vision, is energetically costly. As a compromise, animals (ourselves included) have a region with a high density of narrowly separated photoreceptors called the fovea.

Eagles, like many other birds, actually have two foveas. In the central, main fovea that it uses for hunting, the separation between the cones is 2µm, the absolute limit for the eye to still function correctly. In comparison, our cones are separated by 3µm. The secondary fovea allows the birds a high-resolution field of view to the side of their head as well as directly in front of them. The size of the eyeball is also limited by energetics as well as flight dynamics.

How does packing as many photoreceptors into as small a space as possible increase an eye’s resolution? Consider a digital camera on a phone. When camera phones first came out, the quality of the image was poor, but nowadays, the photos we take with our phones are really very good. That is because engineers have figured out how to add more and more pixels into the small area available for the phone camera chip. This is exactly the same for the tightly packed cones in the eagle eye; more photoreceptors is akin to more pixels, which means a higher sampling of the field of view, which means they can pick up more detail; like a rabbit in bushes from 10,000 feet up.

Visual trade-off

However, by packing more cones into an area, the size of the photoreceptors themselves must decrease. The sensitivity of a photoreceptor to light is directly proportional to its diameter, which makes sense. The larger the area, the more photons it is going to be able to ‘catch’, just like a bigger net will catch more butterflies and any other number of examples you care to think of. So smaller photoreceptors need more light. This is something we struggle with too; how many times when dealing with a small, fiddly task like removing a splinter from someone’s finger have you had to drag them across the room to stand directly under the light in order to see it better? So acuity (resolution) comes at the expense of sensitivity. The old adage; ‘you don’t get something for nothing’ really rings true when it comes to vision. Eagles are faced with a trade off; they need to have eyes capable of detecting very small prey from very far away, but in order to achieve such high resolution, they need a lot of light.

The pupil is another way of controlling the amount of light reaching the photoreceptors. However, a large pupil, while it lets in more light, affects image quality. It reduces the depth of field, the range of objects that are in sharp focus, plus it can cause other image degrading effects such as chromatic aberration. This is where different wavelengths (colours) of light are refracted through the lens by different amounts, which leads to an apparent rainbow effect around the edges of objects that causes a degradation in image quality. So to maintain the integrity of the image, vital when detecting small animals from far away, eagles cannot use pupil dilation. Therefore, the only remaining option is to hunt only when there is sufficient light in the environment. As a consequence, eagles are purely diurnal, returning to their roost as soon as dusk falls and their vision starts to fade.

Rock steady

Eye and head movement is a big factor too. Eagles stabilise their heads very precisely to avoid the degrading effects of motion blur. Almost all animals stabilise their gaze to a certain extent; but eagles are outstanding. Using the phone analogy again, how many times have you watched back footage where the video was barely comprehensible because the phone was moving, even just a little, during filming? The same thing would happen to an eagle’s view of the world if it did not keep its head isolated from the movement of its body in flight; all of those extra photoreceptors, packed into the smallest possible size, would be for nothing.

While eagles have far more powerful eyes than our own when it comes to spotting small objects from far away, it comes at a cost. As soon as the light levels drop, as they do every evening at dusk, an eagle’s acuity quickly falls to below our own. But they have adapted to suit their particular niche; the undisputed monarchs of the sky during the day. Best of all – most of us can accurately claim to have eyesight better than an eagle, just not in the daytime.

Dr Ilse Daly is a research associate at the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol.