[CaptionComponent="2982"]

Accurate and repeatable recording of ocular conditions is fundamental to ‘best practice’ and is of particular importance where successive appointments may well be conducted by more than one eye care practitioner. In order to improve and standardise anterior eye evaluations between practitioners, subjective grading scales were first popularised back in the mid-1990s. These allow the eye to be referenced to standard ‘anchor’ images chosen to comprise a range of clinical presentations of a particular feature or surface of the anterior eye.

Benefits of Grading Scales

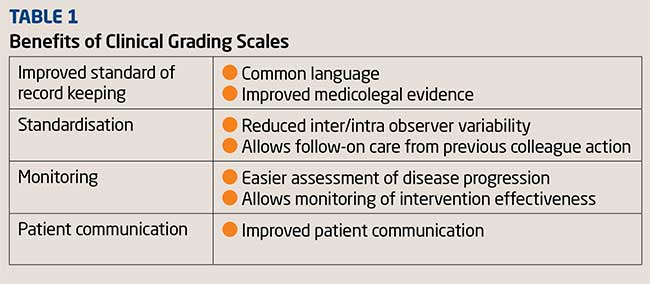

The benefits of clinical grading scales include accuracy and consistency in clinical record keeping leading to more meaningful communication of clinical cases to fellow health professionals. Increased focus on clinical records in cases of complaints and potential legal action means standardised and comprehensive record keeping has added relevance for today’s eye care practitioner.

Clinical grading scales also offer practitioners the most effective way of monitoring the health of an eye wearing a contact lens. They allow for an accurate means of detecting change that can occur during lens use and provide the practitioner with the necessary information to intervene to minimise the risk of a chronic adverse reaction to the contact lens. Table 1 summarises the benefits.

Ideally, prior to contact lens wear, the baseline data for a range of clinical variables should be collected and then be continually monitored throughout the course of the patients wearing experience.

Existing Scales

Clinical grading scales specifically designed for contact lens complications include the original CCLRU (rebranded IER and more recently published under the name of the Brien Holden Vision Institute or BHVI, Figure 1) and Efron scales (Figure 2), both having their supporters and detractors. The latter consists of a series of artist illustrated depictions of 16 different conditions, while the former comprises photographs of 6 conditions, two of which are presented in multiple manifestations.

[CaptionComponent="2983"]

The BHVI photographic scales have been criticised for the lack of perfect homogeneity between images representing the same condition, either in terms of different illumination conditions or variability of size of the area under display. Whilst Efron overcomes these difficulties by encouraging artistic clarity and licence so as to emphasise and isolate the condition that is being evaluated, it is considered by some a departure from the real life situation in as much as different conditions feed and depend on each other and, therefore, occur simultaneously and should appear as such in a single image.

Both clinical grading scales have been published in prominent textbooks and widely distributed around the world, free of charge, by several major contact lens companies. Indeed it is estimated that over 200,000 copies of these scales – usually in the form of laminated A4 reference cards but also in large poster format – have been provided to practitioners in the past 20 years.

More recently, other clinical grading scales have been introduced (see Figure 3)

[CaptionComponent="2984"]

Repeatability

Researchers have examined the repeatability of discrete and continuous anterior segment grading. They conclude that grading scales that are too coarse generally allow less sensitivity in the detection of meaningful clinical changes. Practitioners often overcome this limitation by adopting half-point scales, or by assigning plus and minus symbols next to an integer scale. They also believe that increasing the number of intervals to make the grading scale finer may reduce the degree of concordance between repeated measurements of the same clinical event.

Finer scales have the advantage of being capable of recording clinical change more sensitively. By grading to decimal places that are representative of points in between two successive integer points on the scale, (1.2, 2.4, 3.6) the scale is expanded and the sensitivity (ability of the scale to discriminate a difference) is thereby increased. However, there is a limit to such interpolation; 0.1 increments are generally considered optimal as any finer intervals would promote poor concordance between observers. The variability of grading scores between practitioners can be wide and they generally tend to form clusters around whole numbers. Evidence suggests that concordance tends to improve with training or practice.

Another concern with existing clinical grading scales is that they do not cover all possible clinical appearances, particularly at the severe end of the scale, and that they may not be linear. Objective analysis of digital images provides an attractive alternative to the current subjective nature of practitioner grading, and this has the potential to be more sensitive. The subjective judgement that a practitioner makes at the slit lamp is however a complex one to mimic objectively. The objective grading of ocular redness involves judgement of both the hue and vessel size, relative to the area under question. This is difficult for software to achieve accurately. Approaches to this challenge are still emerging and further developments in this area are anticipated.

One interesting development is the use of ‘morphing’ grading scales, which are accessible digitally within the consulting room either on disc or via customised software, which can be used to show gradual changes from one grade to another by manipulation of a slider (Figure 4).

[CaptionComponent="2985"]

Computerised grading removes the problem of grading between ratings. This may involve the use of movie sequence of images, a CD for the Efron gratings, a phone app, or computer software programs.

The Vision Care Institute Clinical Grading Scales App (Figure 5), compatible with the iPhone, allows practitioners to assess nine conditions (based on TVCI modified Efron Scale) using severity levels that lessen and increase with real-time animation controlled by touch. The app enables levels of severity to be compared side-by-side in 0.1 increments. A report can then be exported for practice records without collecting patient personal data.

[CaptionComponent="2986"]

Nowadays, many practitioners record clinical information electronically by entering data into defined fields within computer-based clinical management software programs – a practice that in effect prompts practitioners to capture all relevant aspects of the presenting signs and symptoms. For example, there may be specific fields for each eye, separate fields for slit lamp findings and previously drawn sketches of the eye, over which text or drawings can be interposed. Paper records may also have specific sections for recording clinical information, as well as previously drawn ocular sketches for annotation.

Practitioners who use photography to document complications admit, in many cases, to also use grading scales. This duplicitous practice represents a conservative approach to record keeping and suggests that many practitioners consider the recording of clinical grades and clinical photography to be complementary approaches.

What can we do to improve clinical grading?

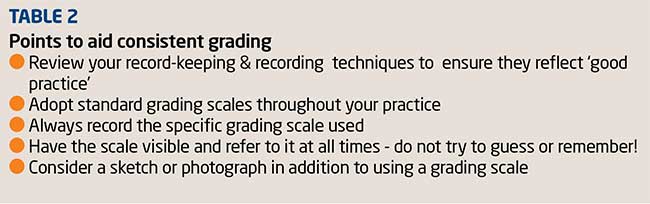

Individually, our grading is repeatable, so we should continue to use the scales in the way we are doing now. What we are not that good at, however, is being consistent with our colleagues. If we are working in settings where patients are being seen by multiple practitioners, it is critical that the same scales be used and the same rules applied, to ensure that numbers assigned to appearance by different practitioners match.

Grading scale grades are not interchangeable, with scales starting either at grade 0 or 1 and with a wide range of values for the highest grade. Practitioners must record the grading scale used, and ideally standardise this within an individual practice or corporate groups. Table 2 summarises some key points to consider.

Two important recent studies help us to reach a more standardised approach. The British Universities Committee of Contact Lens Educators (BUCCLE) circulated a web-based survey covering topics such as the use of description, sketching, grading scales/photographs, paper/computerized record cards, level of precision and average amount of time spent on anterior eye health recording.1 809 practitioners from across the world completed the survey. Word description, sketches and grading scales were used more for recording the anterior eye health of contact lens wearers than other patients, but photography was used by a similar number.

Description, sketches and grading scales were used more for recording the anterior eye health of contact lens patients than other patients, as was photography. 84.5 per cent of respondents used a grading scale, the original Efron (51.6 per cent) and CCLRU/BHI (48.5 per cent) being the most popular, with the more recent published Vision Care Institute (modified Efron) (16.5 per cent) and Jenis (Alcon) (4.4 per cent) less frequently used (Figure 6).

[CaptionComponent="2987"]

Most practitioners graded to the nearest whole unit (47.4 per cent )with just 14.7 per cent to one decimal place (Figure 7). The average time taken to record anterior eye health was 6.8 minutes (+/- 5.7 minutes).

[CaptionComponent="2988"]

The study reached a number of important conclusions summarised in Table 3.

A second study was by Efron et al. 2 An anonymous postal survey containing 16 questions was sent to all 756 members of the Queensland Division of the Optometrists Association Australia, to investigate the extent and pattern of use of grading scales for contact lens complications in optometric practice. The response rate was 31 per cent. The majority of respondents (61 per cent) used grading scales of which 65 per cent were Efron and 25 per cent were CCLRU (BHVI). 53 per cent referred to a hard copy of a grading scale when assessing ocular conditions. 76 per cent used a method of incremental grading rather than grading with whole numbers, 36 per cent utilised plus and negative signs, and a further 36 per cent numerical increments of 0.5 to grade severity of conditions. 53 per cent referred to a hard copy of a grading scale when assessing ocular conditions. Conclusions of this second study were that optometrists grade a diverse array of anterior eye conditions, the three ocular conditions that were found to be the most frequently graded were corneal staining, papillary conjunctivitis and conjunctival redness. This is perhaps not surprising, given that these are common complications often related to patient symptoms and also the subject of extensive discussion in the literature and at conferences.

Another interesting finding was that grading scales are more likely to be used by optometrists who have recently graduated, have a postgraduate certificate in ocular therapeutics, see more contact lens patients or use other forms of grading scales.

The primary reason cited for not using grading scales was a preference for recording clinical data using other means, such as sketches, photographs or written descriptions. These alternative approaches to record keeping can all be considered as representing good clinical practice. The view expressed by a small minority of optometrists was that grading scales constitute an unreliable or inaccurate method of recording clinical data is contrary to published evidence.

The Eye Grading App by Johnson & Johnson Vision Care Companies is currently being upgraded and the latest iOS 9 compatible version will be released in summer 2016. Included in the improved version will be high definition images and compatibility with iPads as well as iPhones.

References

1 JS Wolffsohn et al and the British Universities Committee of Contact Lens Educators (BUCCLE). Cont. Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38:266-271

2 Efron et al - Contact Lens Grading Scales in Practice Clin Exp Optom 2011; 94: 2: 193–199.

Caroline Christie is an independent optometrist specialising in contact lenses