In the first part of this series, we looked in detail at vascular occlusive diseases. To conclude, we will look at hypertensive retinopathy, anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy and some less common but still significant vascular disorders that seriously impact upon the eye.

Hypertensive retinopathy

Hypertension is no doubt a major health concern, affecting about one third of the world’s population1 and is a key risk factor for preventable premature death and disability.2 Hypertension is also known to have many effects on the eye, two of which have already been looked at in the article last month but also others such as cranial nerve palsies and macroaneurysms. Hypertensive retinopathy itself comprises a spectrum of disease ranging from innocuous signs leading the optometrist to refer the patient to their GP to sight and life-threatening signs indicating immediate referral to secondary care.

Risk factors for hypertension

- Increasing age

- Male gender

- Afro-Caribbean race

- Living in an industrialised environment

- Lack of exercise4,6

Accelerated, or malignant hypertension (ie BP over 220mmHg systolic, 120mmHg diastolic) is a major risk factor for more severe forms of hypertensive retinopathy.3

Symptoms of hypertensive retinopathy

Patients are largely asymptomatic, however, accelerated hypertension may cause headaches as well as symptoms resulting from its ocular complications such as visual loss from macular exudates and relative field defects in serous retinal detachment.

Fundus signs

- Diffuse and focal arteriolar narrowing (figure 1 and 2).

- Copper and silver wiring (opacification of arteriole walls leading to an increasingly shiny appearance).

- Arteriovenous nipping (compression of venules by arterioles).

- Haemorrhages (often flame-shaped).

- Cotton wool spots.

- Hard exudates – typically in a ‘macular star’ pattern.

- Papilloedema – severe hypertension leads to an increase in intracranial pressure and optic nerve ischaemia causing the disc to swell.4

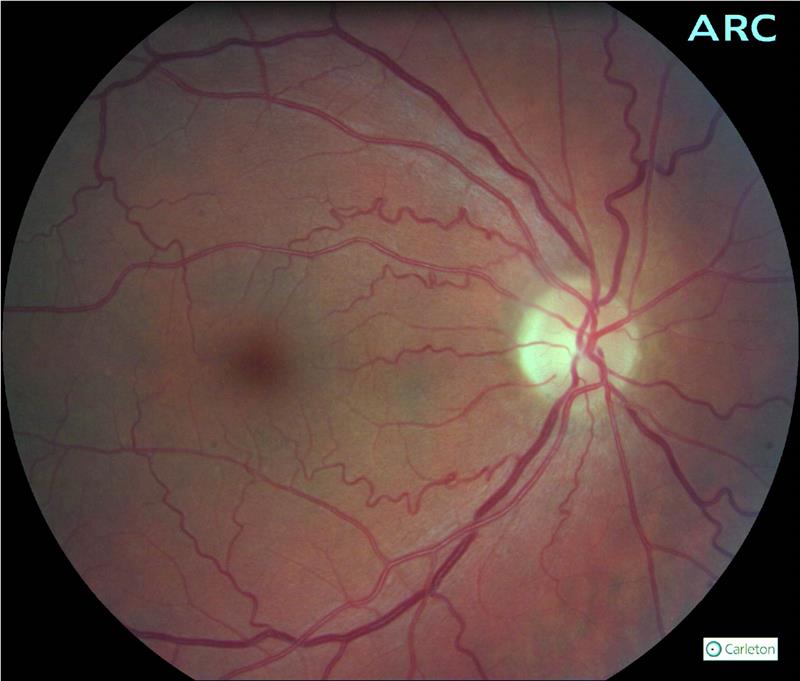

Figure 1: Hypertensive patient showing tortuosity and arteriovenous nipping

In clinical optometric practice, it is common to grade the level of arteriolosclerosis. A common grading scale used is as follows:5

Stage 1 – broadening of arteriolar reflex, arteriolar attenuation, vein concealment.

Stage 2 – more obvious broadening of the reflex, deflection of veins at arteriovenous (AV) crossings

Stage 3 – arteriolar copper wiring, tapering and banking of veins close to AV crossings

Stage 4 – arteriolar silver wiring

Figure 2: Diabetic with hypertension showing tortuosity and arteriovenous nipping

While being choroidal rather than retinal, it is perhaps worth mentioning here Elschnig’s spots (which appear as black spots surrounded by yellow haloes)6 and Siegrist streaks (linear hyperpigmented lesions)7 which are both signs of hypertensive choroidopathy. If severe enough, pathological changes in the choroid may lead to serous retinal detachment.5

Management

Patients with mild hypertensive changes should be referred to their GP for BP measurement and the relevant management. It is outside of the scope of this article to go into the management of systemic hypertension, however, treatment is usually considered when the BP is over 140mmHg systolic or 90mmHg diastolic on two separate occasions.3

Patients with malignant hypertensive changes should be referred to secondary care immediately as they require admission and careful anti-hypertensive therapy.4

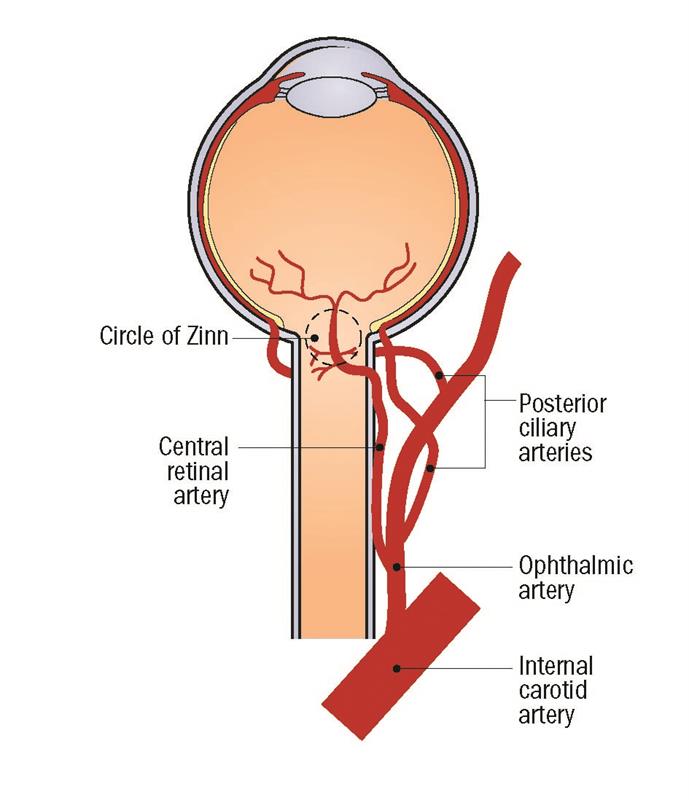

Figure 3: Blood supply to the eye

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

As mentioned in the first article, the short posterior ciliary arteries supply the choroid, outer retina and the anterior optic nerve via the Circle of Zinn (figure 3). Disruption of this blood supply here can lead to infarction of the optic nerve head, leading to anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION) as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

Based on the underlying aetiology AION can be classified as arteritic (A-AION) or non-arteritic (NA-AION). It is important to differentiate the two as, if left untreated, the risk of vision loss in the contralateral eye in A-AION is extremely high (95%). Even when treated this may occur in up to 10%.3 The incidence of NA-AION is approximately 10/100,000,8 and A-AION approximately 1/100,000.9

Risk factors

NA-AION

- Age – patients are typically between 60 and 70 years old (although almost a quarter are under 50).10

- Crowded optic discs11 (also called ‘disc-at-risk’) are thought to cause reduced axoplasmic flow leading to oedema, compression and consequent ganglion cell apoptosis.12

- Disc drusen (figure 5) are thought to contribute to disc

- crowding.13

- Diabetes – around a quarter of patients with NA-AION are diabetic.14

- Hyperlipidaemia – the risk of developing NA-AION is increased by over three times, particularly in younger, non-diabetic patients.15

- Sleep apnoea – almost three-quarters of patients have sleep apnoea.16

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor drugs (eg sildenafil – Viagra).17

- Cataract extraction, especially if there is a history of NA-AION in the fellow eye.18,19

Figure 5: Disc drusen are a risk factor for AION

Hypertension is often listed as a risk. However, studies show mixed results, with some even suggesting a protective effect.10 Smoking is another commonly claimed risk, but has been shown to have no effect.20,21

A-AION

- Giant cell arteritis (GCA) if by far the most common cause.

- Age – patients have a mean age of 76 years.22

- Rarer causes include systemic lupus erythematosus and

- herpes zoster.23

Symptoms

NA-AION

Patients usually present with acute, painless, loss of vision or scotoma in one eye. Two-thirds of the time this is noted on waking, and has been shown to be significantly more common in the summer.24 Unlike A-AION there are no acute systemic symptoms.

A-AION

Patients present with extremely reduced vision in one eye, often preceded by amaurosis fugax and photopsia. Patients also complain of the classic symptoms of GCA;

- Scalp tenderness (eg pain on brushing of the hair).

- Jaw claudication (pain on chewing or talking).

- Malaise.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Headache (localised or generalised).

- Polymyalgia rheumatica (stiffness of proximal muscles, particularly the shoulders).

Clinical investigations

NA-AION

- Hyperaemic disc with segmental swelling.

- Crowded disc in the contralateral eye.

- VA – better than 6/60 in most cases (almost half are 6/9 or

- better).10

- Colour vision – reduced colour vision proportional to VA.

- Pupils – RAPD.

- Visual fields – altitudinal defect (inferior is more common than superior) – figure 6.

Figure 6

A-AION

- Extremely pale, oedematous disc.

- Thick, tender temporal artery which has no pulse.

- VA – usually less than 6/60.

- Pupils – RAPD.

Management in primary care

In both cases, same day referral to ophthalmology is advisable in order to rule out GCA.

Management in secondary care

NA-AION

There is no treatment for NA-AION, but it is important to elicit the underlying systemic cause and initiate the relevant treatment. Patients have their BP, lipid and glucose tested, and the tests for A-AION outlined below.5 Patients are generally referred to vascular physicians and low dose aspirin is often prescribed but there is no proven treatment.25

A-AION

The patient undergoes urgent medical assessment to include ESR, CRP, platelet levels, and urgent temporal artery biopsy (TAB). Treatment is aimed at preserving the vision in the contralateral eye and patients are generally placed on IV or oral prednisolone.

Duration depends on ESR and CRP levels but most receive treatment for 12 to 24 months, but some patients are on a maintenance dose forever. Aspirin is often used. Visual improvement is uncommon and minimal.26

Sickle-cell Retinopathy

Sickling haemoglobinopathies are a group of conditions, which affect more than one in 2,000 births in England. It is more common in people of African, eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern origin.27 They cause abnormal haemoglobin formation leading to unusual erythrocyte morphology (ie they take a sickle shape). The most common forms are:

- Sickle-cell disease (SS) is the most common, and can cause severe systemic symptoms – including chronic haemolytic anaemia, vaso-occlusive disease and excruciating bone marrow infarcts. It causes relatively mild ocular complications.

- Sickle-cell C disease (SC) is the second most common form, and causes less severe systemic symptoms but more severe retinopathy.

- Sickle-cell thalassaemia (SThal) again causes less severe systemic problems, but more severe retinopathy.

- Sickle-cell trait (AS) usually causes no problems, unless patient is under conditions of severe hypoxia.28

Sickling haemoglobinopathies can cause various non-proliferative retinal changes including venous tortuosity, ‘salmon patches’ (preretinal haemorrhages at the equator) and ‘black sunbursts’ (hyperplastic RPE changes secondary to retinal haemorrhage), which are often self-limiting.5 Proliferative changes were first classified by Goldberg in 1971 and they are:29

Stage 1 – peripheral arterial occlusion.

Stage 2 – peripheral arteriovenous anastomoses (‘hair-pin’).

Stage 3 – neovascular proliferations (‘sea fan’).

Stage 4 – vitreous haemorrhage.

Stage 5 – tractional retinal detachment (figure 7).

Figure 7: Tractional retinal detachment

Despite these changes, no treatment is usually required due to autoinfarction of the new vessels. Pan-retinal photocoagulation is occasionally used,3 and intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy has been put forward but not yet widely adopted.28,30 Vitreoretinal surgery is reserved for persistent vitreous haemorrhage, and of course retinal detachment.28 Current NICE recommendations are for all patients with sickle-cell disease is to have an annual ophthalmological assessment.31

Retinopathy of Prematurity

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a proliferative retinopathy affecting children of low gestational age (less than 32 weeks) and weight (less than 1,501g, 3lb 5oz), and exposure to high oxygen tension.3 Up to 68% of babies born with a weight of less than 1,251g develop some form of ROP but most do not require treatment.32 The current joint guidelines from the Royal Colleges of Paediatrics and Child Health and Ophthalmologists state that babies of less than 32 weeks gestational age and 1,501g weight should be screened. Less than 31 weeks and 1,251g must be screened.33 Depending on staging based on the International Classification of ROP34 treatment includes laser photocoagulation, which has replaced the mainstay of many years, cryotherapy. Anti-VEGF therapy is becoming more popular as a treatment, but further investigations into safety and efficacy are indicated.35

Summary

Retinal vascular diseases are a group of conditions which are relatively commonly encountered in optometric practice. With the majority of these conditions having preventable risk factors, preventative eye care will no doubt become more of a part of an optometrist’s day-to-day job. Moreover, treatment of conditions within this realm are rapidly evolving and it is imperative that optometrists keep up-to-date with them.

Ceri Probert is an optometrist who practises in south Wales.

References

1 Falaschetti E, Mindell J, Knott C, Poulter N. Hypertension management in England: a serial cross-sectional study from 1994 to 2011. Lancet 2014;383(9932):1912-1919.

2 Floyd CN. Hypertension – state of the art 2015. Clinical Medicine 2016;16(1):52-54.

3 Denniston AKO, Murray PI. Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2014. xxxiv, 1,069.

4 Wong T, Mitchell P. The eye in hypertension. Lancet 2007;369(9559):425-435.

5 Kanski JJ, Bowling B, Nischal KK, Pearson A. Clinical Ophthalmology: a systematic approach. Expert consult. 7th ed. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2011.

6 Devenecia G, Wallow I, Houser D, Wahlstrom M. The eye in accelerated hypertension .1. Elschnig spots in nonhuman-primates. Archives of Ophthalmology 1980;98(5):913-918.

7 Puri P, Watson AP. Siegrist’s streaks: a rare manifestation of hypertensive choroidopathy. Eye 2001;15:233-234.

8 57. Hattenhauer MG, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, Grill R, Gray DT. Incidence of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1997;123(1):103-107.

9 Hayreh SS. Posterior ciliary artery circulation in health and disease – The Weisenfeld Lecture. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2004;45(3):749-757.

10 Kerr NM, Chew SSSL, Danesh-Meyer HV. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: A review and update. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2009;16(8):994-1000.

11 Jonas JB, Xu L. Optic disc morphology in eyes after nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 1993;34(7):2260-2265.

12 Beck RW, Servais GE, Hayreh SS. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy .9. Cup-to-disk ratio and its role in pathogenesis. Ophthalmology 1987;94(11):1503-1508.

13 Purvin V, King R, Kawasaki A, Yee R. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in eyes with optic disc drusen. Archives of Ophthalmology 2004;122(1):48-53.

14 Newman NJ, Dickersin K, Kaufman D, Kelman S, Scherer R. Characteristics of patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy eligible for the ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial. Archives of Ophthalmology 1996; 114(11):1366-1374.

15 Deramo VA, Sergott RC, Augsburger JJ, Foroozan R, Savino PJ, Leone A. Ischemic optic neuropathy as the first manifestation of elevated cholesterol levels in young patients. Ophthalmology 2003;110(5):1041-1046.

16 Mojon DS, Hedges TR, Ehrenberg B, Karam EZ, Goldblum D, Abou-Chebl A, Gugger M, Mathis J. Association between sleep apnoea syndrome and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Archives of Ophthalmology 2002;120(5):601-605.

17 Pomeranz HD, Bhavsar AR. Nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy developing soon after use of sildenafil (Viagra): A report of seven new cases. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 2005;25(1):9-13.

18 McCulley TJ, Lam BL, Feuer WJ. Incidence of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with cataract extraction. Ophthalmology 2001;108(7):1275-1278.

19 Lam BL, Jabaly-Habib H, Al-Sheikh N, Pezda M, Guirgis MF, Feuer WJ, McCulley TJ. Risk of non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION) after cataract extraction in the fellow eye of patients with prior unilateral NAION. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2007;91(5):585-587.

20 Hayreh SS, Jonas JB, Zimmerman MB. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and tobacco smoking. Ophthalmology 2007;114(4):804-809.

21 Newman NJ, Scherer R, Langenberg P, Kelman S, Feldon S, Kaufman D, Dickersin K, Ischemic Optic Neuropathy D. The fellow eye in NAION: Report from the ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial follow-up study. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2002;134(3):317-328

22 Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1998;125(4):509-520.

23 Hayreh SS. Management of ischemic optic neuropathies. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 2011;59(2):123-136.

24 Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: Time of onset of visual loss. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1997;124(5):641-647.

25 Hayreh SS. Ischemic optic neuropathy. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2009;28(1):34-62.

26 Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B, Kardon RH. Visual improvement with corticosteroid therapy in giant cell arteritis. Report of a large study and review of literature. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica 2002;80(4):355-367.

27 Dick M. Sickle cell disease in childhood standards and guidelines for clinical care. In: Programme, London: NHS Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Screening Programme; 2010.

28 Elagouz M, Jyothi S, Gupta B, Sivaprasad S. Sickle Cell Disease and the Eye: Old and New Concepts. Survey of Ophthalmology 2010;55(4):359-377.

29 Goldberg MF. Classification and pathogenesis of proliferative sickle retinopathy. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1971;71(3):649-&.

30 Mitropoulos PG, Chatziralli IP, Parikakis EA, Peponis VG, Amariotakis GA, Moschos MM. Intravitreal Ranibizumab for Stage IV Proliferative Sickle Cell Retinopathy: A First Case Report. Case reports in ophthalmological medicine 2014;2014:682583-682583

31 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2010 28 June 2016. Sickle cell disease. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

33 Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, Royal College of Ophthalmologists,. Guideline for the Screening and Treatment of Retinopathy of Prematurity. London 2008.

34 Gole GA, Ells AL, Katz X, Holmstrom G, Fielder AR, Capone A, Flynn JT, Good WG, Holmes JM, McNamara JA and others. The international classification of retinopathy of prematurity revisited. Archives of Ophthalmology 2005;123(7):991-999.

35 Tawse K, Jeng KW, Baumal CR. Practice Preferences in Treatment of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP). Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2015;56(7)