This series has so far looked at the nature of retinal detachment and posterior vitreous detachment, the various risk factors and causes, and how it might be best identified and assessed. This final article looks now at the various management options available to the eye care professional.

The challenge

Patients with new onset flashes and floaters commonly present initially to their optometrist. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate co-management with secondary care in the Hospital Eye Service (HES) is essential. Pathways have been developed in Scotland and Wales, but the situation in England is much more varied. Some districts have a protocol initiated by the local eye unit (eg Norfolk & Norwich Hospital1) but in many areas there is still no structure to support optometrists and allow them to play a role in relieving some of the pressure on secondary care. The need for this was highlighted in the recent NHS England eye health summit ‘Immediate solutions to address demand and capacity pressures in the Hospital Eye Service’.2 Fortunately the profession has, for some time, been developing Minor Eye Condition Services (MECS) and an increasing number of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) are making use of these local schemes. A report3 on the original Welsh Pears scheme listed the most common reasons for patients to present to an accredited optometrist in Wales. Flashes and floaters were the third most common symptom after red eye and discomfort/ irritation. The challenge is for optometrists to take on the role of triaging patients with PVD symptoms to exclude retinal detachment or tears.

Incidence of tears and associated signs

It is known that 10-15% of acute symptomatic PVD cases will develop a retinal break,4 most likely a horse-shoe tear (HST). At least half of symptomatic HSTs would progress to a retinal detachment if they were not treated. Thus it is vital all HSTs are identified and referred urgently for laser retinopexy, to prevent them developing into a retinal detachment. Two other signs are highly predictive of retinal tears. When vitreous haemorrhage is associated with PVD there is 70% chance that a retinal break will also be found.5,6 Tobacco dust (Shafer’s sign) correlates with a 90% risk of retinal tears.7,8

Figure 1: Copious tobacco dust, left, and small area of harder to spot dust, right

Symptoms

Scrutiny of legal complaints shows that the most common failure is in recognising that a PVD has occurred and acknowledging that a dilated exam is necessary. Analysis of history and symptoms, bearing in mind risk factors, was described in part two of this series. Remember that flashes and floaters are not the only symptoms of PVD. When the posterior hyaloid membrane comes forward away from the retina it can disrupt vision in a vague way that patients find difficult to describe. Some say a veil drifts across their central vision, while others say it is like looking through a dirty pain of glass. Usually there is no definite reduction in Snellen acuity. If a patient over the age of 50, reports a change in the quality of vision that is both sudden and in one eye, the optometrist should rule out any obvious causes and then manage this as a symptom of PVD. The term ‘fuzziness’ does not adequately describe the visual symptoms caused by the detached posterior hyaloid membrane, but it serves as a reminder that flashes and floaters are not the only symptoms of a PVD.

Symptoms can include:

- Floaters

- Flashes

- Fuzziness

Retinal detachment symptoms may also include:

- Field defect

There is a temptation to regard multiple symptoms, for example flashes combined with floaters, as being more serious and more deserving of full examination by dilation. Several studies have tried to analyse symptoms, but it was found that it was not possible to predict the likelihood of a retinal tear on the basis of symptomatology alone.8,9 When an optometrist is presented with a patient whose symptoms suggest PVD, the approach should be: this patient has a one in 10 chance of having a retinal tear. The symptoms will not tell me if he is among the unlucky 10%, he needs a dilated examination in order to find out. How this fits in to the appointment schedule is a practice management problem and there should be a contingency plan for this. It is important that optometrists should feel free to make the correct clinical decision, without being swayed by time constraints and other practical considerations. Remember that there is the option of dilated examination the next day or referral either to the HES or to another optometrist.

Examination

Examination is directed towards detecting retinal detachment, tears, tobacco dust, and vitreous or pre-retinal haemorrhage.

Tobacco dust

Some optometrists believe tobacco dust can be detected without dilation because it appears in the aqueous that lies between the lens and the anterior vitreous face (Berger’s space). This would be good if it were true. Unfortunately it is unlikely that pigment cells or granules could readily penetrate into the aqueous. The anterior hyaloid membrane is composed of densely packed cross-linked lamellae of collagen fibrils, and forms a strong boundary which is firmly attached to the underlying retina at the vitreous base. There is no reason to suppose that the anterior hyaloid membrane becomes disrupted by the processes of PVD. It is of course possible that there could be a defect in this membrane, for example following posterior capsule rupture in cataract surgery, but even if tobacco dust does get into the aqueous occasionally this does not mean this is a good place to look for it. Nor is there any reason for it to come to rest behind the lens rather than fall to the lowest point. Tobacco dust occurs when RPE cells are liberated from the site of the retinal tear into the vitreous. Optometrists must search in the vitreous and must disregard this misleading notion about Berger’s space. Both pupil dilation and agitation of the vitreous by abrupt eye movements are essential in order that as much of the vitreous as possible passes through the slit lamp field of view.

Some retinal tears can be easily missed which makes the search for tobacco dust even more important. One small study10 suggested that training and experience is related to the ability to detect Shafer’s sign. It showed a moderate agreement between the consultant and the SHO grade trainee, but only a fair agreement between consultant and the optometrist. This emphasises that using the correct technique is vital and sessions observing in a VR clinic could be beneficial.

Dilation

Optometrists must dilate in order to be able to justify that they have done enough to exclude the presence of a tear. Dilation is also essential to allow an adequate search for tobacco dust and haemorrhage. This does not mean you could never find these features without dilation, just that you must dilate in order to say they are not present. Some advocate a quick vitreous and fundus examination while the patient is at the slit lamp for the pre-dilation check for narrow angles. It is possible this could reveal a tear, tobacco dust, or haemorrhage and the patient could be referred on immediately, taking less chair time and arriving at secondary care sooner. Remember, if nothing is found then you must proceed to dilation in order exclude referable pathology.

Obviously maximal dilation is required so you can search as far as possible into the periphery. This is best achieved by the use of both an antimuscarinic to relax the sphincter and a sympathomimetic to stimulate the dilator. Tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine 2.5% should be instilled after checking for RAPD and excluding a narrow angle with the Van Herick technique. Optometrists can be reassured by the systematic review by Pandit and Taylor11 that the risk of inducing acute closed angle glaucoma, even with combined agents is very low (between 1 in 3,380 and 1 in 20,000). This risk is infinitesimal when set aside the 10% risk of there being a tear which you could miss by not dilating. If the modified Van Herick grade is 25% or 15% warn the patient about the symptoms of a closed angle attack (pain, hazy vision, nausea) and give information about the nearest eye A&E. If the post mydriatic IOP is increased by more than 5mmHg consider immediate referral, but remember the spike in IOP may be delayed. A patient with a modified Van Herick grade 5% may need to be managed in the HES.

Is scleral indentation necessary?

The gold standard technique for detection of retinal tears has always been considered to be indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral indentation, which permits dynamic examination right up to the ora serrata (figure 2). However, this procedure has its disadvantages. It is more time consuming, uncomfortable to the patient12 (but never painful if performed correctly), and is best carried out with the patient lying down, which may be impractical. Most importantly it is a skill that takes time to master and continual practice to maintain. With this in mind, a year-long prospective study was carried out to compare the diagnostic accuracy of slit lamp Volk lens examination with head-set BIO and indentation, in the detection of retinal tears. The results of this small study,13 published in 2003, showed while the majority of tears were picked up at the slit lamp, two (11%) were missed.

Figure 2: Headset BIO with indentation has disadvantages

These two missed tears would seem to confirm the need for scleral indentation, but it is worth looking at them in more detail. One was very close to the ora serrata, which is unusual in the absence of trauma. Scleral indentation is definitely required to check for retinal dialysis which does occur at the ora, but this is not a break that is related to PVD and flashes or floaters. Remember that when you are investigating flashes and floaters, it is PVD-related breaks you are looking for, which are most likely to occur between the equator and the vitreous base. PVD does not normally progress into the vitreous base because of the very strong attachment there, so very few tears will be missed by not inspecting up to the ora. On the other hand, seeing the ora serrata is confirmation you must have examined all the at-risk area of retina up the vitreous base.

The other missed tear was located in an area of pigmented lattice degeneration. The flap of the tear only became visible when the indenter was rolled under the lesion, allowing it to be viewed from a slightly different angle. This illustrates the main advantage of indentation in the detection of tears and emphasises the need for optometrists to refer urgently any lesions they are not certain about. It is easier to detect tears if you remember the underlying retina viewed through a fresh tear will appear more red than its surroundings. Also remember to use maximum illumination when inspecting suspicious areas. Patients can generally tolerate a bright light when it is shone on the peripheral retina and not at the posterior pole.

Scleral indention still has its devotees, but in the UK many ophthalmologists believe when slit lamp Volk lens examination is carried out competently it will detect almost all tears. Table 1 summarises the differences between the two techniques. This is also a topic of debate in the USA. A small study12 published last year, concluded scleral indentation did not provide any additional diagnostic benefit. The author noted the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines were only supported by the lowest strength of evidence and he called for further discussion about the most effective and efficient way to detect peripheral retinal pathology. Here in the UK, a study is being set up in Cambridgeshire to test the diagnostic accuracy of community optometrists against indirect ophthalmoscopy with indentation by a VR specialist.

Table 1: Comparison of slit lamp BIO and head set BIO with indentation

If the optometrist relies on a slit lamp indirect lens it must be one that it is designed for the purpose, such as the Volk Superfield (figure 3) or Volk Digital Widefield, which will provide a clear view further into the periphery. Remember you must gain a view up to the vitreous base. Unfortunately this is not a structure that can be identified visually and the only landmark in the far periphery is the ora serrata, which you are unlikely to see without scleral indentation. There is no equivalent in retinal examination of the sat-nav to tell you how much ground you have covered, so the strategy must be to view as far as you possibly can into the periphery. You need the co-operation of the patient to best achieve this. Ask them to move their eye as far as possible in each of the eight cardinal directions of gaze. Check they can do this properly by having a demonstration run without the lens. This will save confusion and missed areas of retina if the eye is moved erratically in the wrong direction, or by an insufficient amount. Also, hold the lens at the correct distance from the eye (4 to 5mm in the case of the digital widefield) and manipulate it carefully to optimise the field of clear vision. It is best to have a routine, for example, starting superiorly and working your way around the clock in one direction. Perform as many circuits as necessary to feel confident that you can exclude a tear, and do not miss areas in the mid periphery because you are concentrating on the outermost retina. Peripheral lens opacities or the edge of intraocular lens can be a distraction and the best approach is to try to focus through them to the underlying retina.

Figure 3: Field of view should influence choice of fundus viewing lens – the SuperField lens, left, or Digital Widefield is preferable

Other fundus examination methods

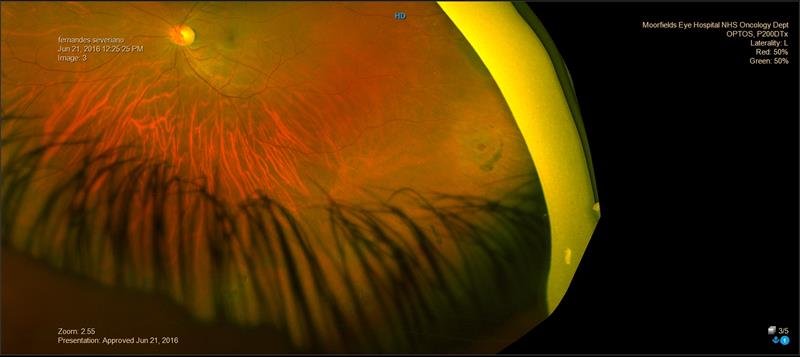

Head-set BIO will give a slightly wider view than a slit lamp, even without scleral indention. The same applies to slit lamp lenses that contact the cornea such as the three mirror lens. The Optos scanning laser imaging gives an extremely wide angle view (figure 4) and would be useful as an initial screening device, but small tears could be missed, especially in areas that are obscured by lashes. Optos should therefore not be relied on to be the sole method of excluding the presence of retinal tears or detachment.

Figure 4: Optos image of atrophic round hole with pigment tide-mark. Note, there are other holes but these are obscured by the lashes

Redundant tests

Some protocols require checking for a relative afferent papillary defect (RAPD), and for lower IOP in the affected eye. These are both signs found in retinal detachment, but only if a substantial area of retina has become detached, which would be easily seen when dilated ophthalmoscopy is carried out. This does not mean it is not good practice to check pupil reactions and IOP prior to dilation. It just means these tests add no diagnostic value to the dilated fundoscopy that is to follow. Similar arguments apply to visual field testing. Sixty degree fields will only reveal a large detachment and will miss a small peripheral detachment.

Is follow up required?

The current policy is that all flap tears are treated with laser as soon as possible to prevent them developing into a retinal detachment. We know from work done before laser retinopexy was available that if a tear is to develop into a detachment it will do so within six to eight weeks14 of the first symptoms. This means that PVD symptoms of over two months’ duration are of much less concern than ones of recent onset. Do patients require follow up during this six to eight week period? Is there a chance that a new tear could develop in the weeks following the initial examination for a symptomatic PVD? A study9 in 1996 addressed this question. They found that new breaks, not apparent at the initial examination, were detected at 1.9% of the follow-up visits. Only one was a flap tear, and therefore only one required treatment, but the authors believed this demonstrated the need for follow-up visits. Three years later a different group15 published work refuting this. They found that round holes were missed in two patients at the first visit because of vitreous haemorrhage, but no new breaks developed in the patients that could be examined fully at the initial visit. Later a meta-analysis16 of previous studies found that 1.8% of patients had retinal tears that were not seen on initial examination. Of the 29 patients with delayed-onset retinal breaks,24 (82.8%) had at least one of the following: vitreous haemorrhage at initial examination, haemorrhage in the peripheral retina at initial examination, or new symptoms. The current practice in the majority of eye departments is not to follow up symptomatic PVD patients who were clear of retinal tears at the initial visit. However, it is always stressed to the patient that they should return without delay if they get new symptoms. This includes a very definite change in floaters, for instance the simultaneous appearance of numerous black dots, which could indicate a new vitreous haemorrhage. Patients are also asked to return if there is a marked increase in the frequency of light flashes. The most ominous new symptoms are, of course, deteriorating vision or a visual field defect (a shadow or veil that remains in a constant position in the peripheral vision). Verbal explanation should be supported by printed material (available to download from various websites).17,18,19

Guidance and protocols

The gradual acceptance of a role for optometrists in triaging patients with flashes and floaters has meant that guidance has had to be amended. In March 2015 the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) published a revised clinical knowledge summary (CKS)20 This provides guidance for primary healthcare professionals who are presented with patients experiencing new onset flashes and/or floaters. The revised guidance draws up two different pathways. One is for high risk patients and stipulates immediate examination on the same day, by an ophthalmologist. The other requires assessment within 24 hours, but this can be done by any practitioner competent in slit lamp examination (of the vitreous) and indirect ophthalmoscopy, which are both core competencies for optometrists (table 2). The mode of indirect ophthalmoscopy is not specified and there is no mention of scleral indentation. The route that the patient takes depends on whether there are changes in visual acuity, visual field loss or signs seen on fundoscopy.

Table 2: Referral pathways for detachment symptoms

These criteria are designed to filter out those patients who are most likely to have a retinal detachment and send them directly to ophthalmology. Field loss is an obvious sign of detachment. Distorted or blurred vision is supposed to take in cases of macula off detachment or vitreous haemorrhage (which is a strong indicator of a retinal tear). It is not intended to encompass the vague change in the quality of vision that is caused by the detached posterior hyaloid membrane.

The revision of the NICE KCS was requested jointly by the Colleges of Ophthalmology and Optometry. Its significance is that it permits a role for optometrists, which was unclear in the previous version. The NICE guidance is really aimed at GPs, and optometrists will find the guidance21 produced by their own College much more helpful.

It states that if you suspect a retinal break or tear you should, as a minimum:

- Take a detailed history and symptoms, looking for particular risk factors.

- Examine the anterior vitreous to look for pigment cells.

- Perform a dilated fundal examination, using an indirect viewing technique.

The guidelines state if you take on the task of examining the patient you should continue until you have sufficient information to make a clinical decision. Two outcomes are proposed. The first is urgent, within 24 hours referral to the HES if any of the following are found:

- Retinal detachment.

- Tobacco dust.

- Haemorrhage (vitreous, retinal or pre-retinal).

- Any retinal break (tear, atrophic round hole, operculated hole).*

- Lattice retinal degeneration.*

*In the presence of PVD symptoms

The second outcome is to manage the patient in your practice. This can be done providing:

- There is a PVD.

- Vision is unchanged.

- No retinal tear or detachment.

- No tobacco dust.

- The patient is well informed about the symptoms that should prompt an urgent review.

- You issue written information to support your diagnosis and advice.

Other useful guidance is given on general principles. Optometrists who do not feel competent to examine a patient presenting with flashes and floaters are encouraged to refer to the HES or another optometrist. The same applies if you are not confident your examination has ruled out the important diagnostic signs. Frontline or support staff should be trained to deal with such a patient who contacts the practice. Patients should be told a diagnosis cannot be reached without an examination. Full and accurate records of all patient contact should be kept. The most important guidance is you should follow local protocols for the management and referral of these patients.

The College guidelines have to apply to all optometrists, regardless of expertise and experience, and therefore have to take a cautious approach. According to the College guidelines, cases of lattice, atrophic round hole or operculated hole, which are relatively low risk, have to be seen within 24 hours along with tears and detachments which definitely do need treatment. This is partly because the College guidelines have only two clinical outcomes, which are either, immediate referral within 24 hours or manage within your own practice. This means all cases requiring an ophthalmology opinion have to be seen urgently regardless of the magnitude of risk. Schemes for accredited optometrists are better able relate the urgency of referral to the actual risk. For example the protocols for the LOC Central Support Unit Mecs pathway22 and the Eye Health Examination Wales (EHEW) clinical manual,23 have the option to have the patient seen in the next vitreoretinal clinic rather than within 24 hours. However, these protocols cannot take into account the variation in clinical practice between different eye units. For example, at one hospital they perform laser retinopexy around all operculated holes as a precaution, even when there are no longer any symptoms. In contrast, the policy at another hospital is not to treat any operculated holes, because the presence of the operculum, floating above the hole, demonstrates that there is no longer any traction there. The best option is to request your local eye unit to draw up an urgency of referral ranking for the different retinal breaks, indicating how this changes with the presence of risk factors and symptoms. You also need to know how to make the referral, whether it is, by phone, by fax, NHS.net secure email, or by letter given to the patient. It is wise to confirm that a fax or email has been received.

The protocol drawn up by the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital1 stipulates the routine for tobacco dust search should be ‘slit lamp exam with dilated pupil’. This important point is often not made clear enough in other guidelines. Trevor Warburton24, clinical adviser to the AOP legal team, confirms dilation is necessary. Unfortunately, he sees clinical records with the note ‘Shafer negative’ when the pupil has not been dilated. This would leave the practitioner very vulnerable in the event of a complaint. If you see tobacco dust without mydriasis that is definitely Shafer positive, but if you do not see it, you cannot be certain it is not there. You must dilate in order to exclude tobacco dust (or vitreous haemorrhage).

Referral letters

In the case of a retinal detachment, it is vital the patient is directed to an eye unit that has the facilities and specialist clinicians for vitreoretinal surgery. Delay in treatment of macula on detachments can have serious implications for the eventual visual outcome. Always refer direct, never via the GP.

The Locsu pathway22 gives a good summary of the requirements for a referral letter:

- A clear indication of the reason for referral (eg retinal tear).

- Brief description of any relevant history and symptoms.

- Location of any retinal break, detachment or lattice

- degeneration. Use clock hours as well as terms like superior temporal. A drawing with the macula and disc included for scale is useful.

- In the case of retinal detachment whether the macula is on or off.

- Your estimate of the urgency of referral.

Conclusion

This series of articles set out to promote an understanding of retinal breaks and the different mechanisms of detachment, with particular emphasis on those associated with PVD. Assessing symptoms and risk factors is very important. The SOAP format provides a good template for directing the questioning and examination of a patient who presents with flashes and floaters. Optometrists have the skills to examine the fundus and are ideally placed to triage patients, referring when appropriate and counseling the remainder. This takes pressure off the hard pressed HES, promotes our profession, but most importantly, it is a satisfying way to help our patients.

Dr Graham Macalister is a specialist optometrist at Moorfields Eye Hospital.

References

1 www.nnuh.nhs.uk/publication/flashes-floaters-referral-guidance-for-community-optometrists-v3.

2 england.nhs.uk/2016/06/eye-health-summit-2.

3 Sheen NJ, Fone D, Phillips CJ, Sparrow JM, Pointer JS, Wild JM. Novel optometrist-led all Wales primary eye-care services: evaluation of a prospective case series.Br J Ophthalmol. 2009 Apr;93(4):435-8.

4 D’Amico, DJ (2008) Clinical practice. Primary retinal detachment. New England Journal of Medicine 359(22), 2346-2354.

5 Sarrafizadeh R, Hassan TS, Ruby AJ, et al. Incidence of retinal detachment and visual outcome in eyes presenting with posterior vitreous separation and dense fundus-obscuring vitreous hemorrhage. Ophthalmology 2001;108:2273-8.

6 Hikichi T, Trempe CL. Relationship between floaters, light flashes, or both, and complications of posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:593-8.

7 Brod RD, Lightman DA, Packer AJ, Saras HP. Correlation between vitreous pigment granules and retinal breaks in eyes with acute posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1366-9.

8 Tanner, V, Harle, D, Tan, J, Foote, B, Williamson, TH, Chignell, AH. Acute posterior vitreous detachment: the predictive value of vitreous pigment and symptomatology. British journal of ophthalmology, Nov 2000, vol 84, no 11, p 1264-1268.

9 Dayan MR, Jayamanne DG, Andrews RM, Griffiths PG. Flashes and floaters as predictors of vitreoretinal pathology: is follow-up necessary for posterior vitreous detachment? Eye. 1996;10 (Pt 4):456-8.

10 Qureshi, F, Goble, R. The inter-observer reproducibility of Shafer’s sign. Eye, Mar 2009, vol 23, no 3, p 661-662.

11 Pandit RJ, Taylor R. Mydriasis and glaucoma: exploding the myth. A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2000 Oct;17(10):693-9.

12 Shukla SY, Batra NN, Ittiara ST, Hariprasad SM. Reassessment of Scleral Depression in the Clinical Setting. Ophthalmology. Nov 2015, Volume 122, Issue 11, 2360-2361.

13 M Natkunarajah, C Goldsmith and R Goble. Diagnostic effectiveness of non-contact slitlamp examination in the identification of retinal tears. Eye (2003) 17, 607-609.

14 Davis MD. Natural history of retinal breaks without detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;92:183-9.

15 Richardson PSR, Benson MT, Kirkby GR. The posterior vitreous detachment clinic: do new retinal breaks develop in the six weeks following an isolated symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment? Eye. 1999 Apr;13 (Pt 2):237-40.

16 Coffee RE, Westfall AC, Davis GH, Mieler WF, Holz ER. Symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment and the incidence of delayed retinal breaks: case series and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 Sep;144(3):409-413.

17 college-optometrists.org/en/knowledge-centre/publication/patient-leaflets/download.cfm.

18 aop.org.uk/advice-and-support/for-patients/eye-conditions/flashes-and-floaters.

19 moorfields.nhs.uk/condition/flashes-and-floaters.

20 cks.nice.org.uk/retinal-detachment.

22 locsu.co.uk/uploads/community_services_pathways_2015/locsu_mecs_pathway_rev_14_03_16,_v3.pdf.

23 www.eyecare.wales.nhs.uk/ehew.

24 Warburton T, Detachment issues. Optometry Today. March 2016 vol 56.03.