Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness registration in the western world.1 As mentioned in part one of this series, a rapidly ageing population has raised the priority of reducing the risk for age-related eye diseases; the Macular Society has recently called for collaboration so that more AMD research is conducted and additional help is given to those with the condition.

Our research shows that patients with AMD would appreciate greater clarity from eye care professionals regarding their diet and nutritional supplementation. Patients reported that eye care practitioners were not giving consistent advice regarding nutrition, and reported confusion as to what advice, if any, to follow.2 However, there are currently no clear-cut guidelines for practitioners to follow when advising patients about nutrition. Practitioners are often unsure, or lack confidence, when giving advice outside of their area of expertise, even when this advice is consistent with general health advice.3

Clinical decision-making aid

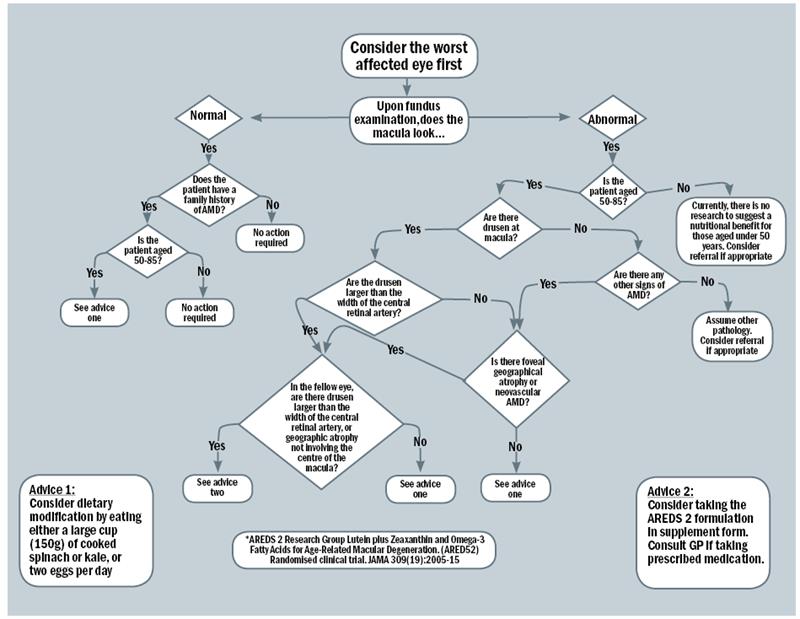

In order to facilitate best practice for patients, eye care professionals need to be providing consistent advice to patients, ideally face-to-face. In part two of this series, the design and evaluation of a clinical decision-making aid will be discussed – an aid that can help eye care professionals provide accurate advice to patients. Such tools can be described as decision ‘trees’, flow diagrams, information flow diagrams, pathways or flowcharts, and show the visual representation of the sequence of steps and decisions needed to perform a process linked together by connecting lines and arrows.

Because they use symbols or diagrams, they are able to be used in settings where time is limited since users can absorb information very quickly. Flowcharts are often space efficient too, and can be placed on clinic walls or pin boards so practitioners can have easy access. As such, a flowchart makes an ideal clinical decision-making aid for all practitioners to use, and an ideal way to implement an intervention for consistent nutritional advice for patients with AMD.

The team at Aston University designed a clinical decision-making aid to help practitioners decide ‘when and what nutritional advice to give to patients with, or at risk of, AMD’. The AREDS 2 supplement is the most up-to-date formula that has been proven to be beneficial in a large randomised clinical trial. The AREDS 2 inclusion and exclusion criteria can be used to decide when it is appropriate to advise the AREDS 2 supplementation. Participants of the AREDS 2 trial were either men or women aged 50 to 85 years at the qualification (initial) visit. They had to have bilateral large drusen (≥125 microns) or large drusen in one eye and advanced AMD in the fellow eye. A study eye (eye without advanced AMD) may have had definite geographic atrophy not involving the centre of the macula without evidence of drusen.4

The flowchart (figure 1) was initially drafted with ‘yes’ and ‘no’ decision lines. The top of the flowchart started with consideration of the retinal examination of the worst affected eye. If a patient had a normal macula but had a family history of AMD, a branch of decisions was created to determine whether they would benefit from dietary modification. If the patient’s macula had an abnormal appearance or there were abnormal signs, the branches following determined whether the patient fitted into the AREDS 2 inclusion criteria, or whether they would benefit from dietary modification only. If the findings were not related to AMD, referral for an ophthalmological opinion was advised. The final outcomes were split into either dietary modification (advice one), or supplementation (advice two).

Figure 1: The clinical decision making flowchart

Pilot testing of the flowchart was conducted by sending the flowchart to 25 optometrists connected to Aston University who worked in hospital, independent, multiple and university practices by email, asking for their input into the usability of such an aid. The optometrists were asked to comment on any aspect of the flowchart. All 25 provided positive feedback, with some also providing useful comments about how to amend the aid to make it more user-friendly – for instance by defining terms like ‘geographic atrophy’ with photos. These suggestions were incorporated into the final version.

Practitioner intervention

A key outcome of using the flowchart is not only to identify which patients would benefit from nutritional supplementation or dietary modification, but also to increase the confidence of practitioners in giving advice on dietary intake. Self-efficacy is a measure of the confidence a person has in their ability to perform a behaviour, such as give dietary advice to AMD patients.5 Self-efficacy was measured to assess the impact of using the flowchart on practitioner’s confidence. Evaluating self-efficacy using scales gives researchers an idea of whether a subject is likely to accomplish a task in the future. Self-efficacy scales have been used in many surveys of medical practitioners’ confidence in performing certain procedures, or giving advice to patients.3,5,6 Moreover, a survey of clinicians’ perceptions of computerised protocols demonstrated that the biggest predictor of intention to use a computerised protocol was beliefs about self-efficacy,7 highlighting how important self-efficacy is in following advice.

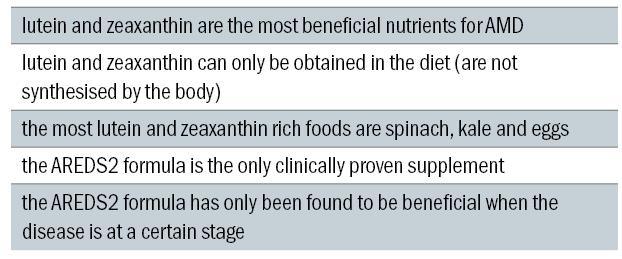

Table 1: Key facts for patients

A practitioner intervention was designed as a two-pronged project as it was conducted on two groups of participants; qualified optometry practitioners and student optometry practitioners. Qualified practitioners initially completed a baseline self-efficacy survey, and then received the flowchart and completed a final self-efficacy survey after two week’s use in optometric practice (hospital or high street). Student practitioners were split into two groups – those that received the flowchart, and those that received a CET article. Student participants initially completed a set of clinical scenarios where participants had to decide which course of treatment, referral or advice was appropriate for a set of hypothetical patients. The student participants also completed a baseline self-efficacy survey, then received the flowchart or article and asked to repeat the clinical scenarios and complete a final self-efficacy survey.

The qualified eye care practitioners felt more confident giving nutrition advice to AMD patients after using the flowchart for two weeks. This is regardless of the gender or age of the participant, or number of years practising. Qualified practitioners gave positive feedback about the flowchart and felt that it had enhanced their clinical practise skills. The results show that the flowchart is a useful tool in a qualified eye care practitioner population regardless of how long they had been a practitioner.8

Student optometric practitioners also felt more confident giving nutrition advice after having received the flowchart. Those using the flowchart reported higher self-efficacy scores than those that received the continuing education article, and receiving the flowchart led to participants making more correct decisions than participants receiving the article. Impressively, flowchart participants appeared to improve the most at the hardest scenarios.

Once the participants had received their educational materials, Group ‘article’ increased the average correct responses in scenario three to 8%, but group ‘flowchart’ increased the average correct responses to 57.7% – this is a 25-fold increase. Group ‘flowchart’ appeared to have performed best at the tasks which were the hardest. The results also show that the flowchart is a useful tool in a student practitioner population and could be used in final year undergraduate studies.8

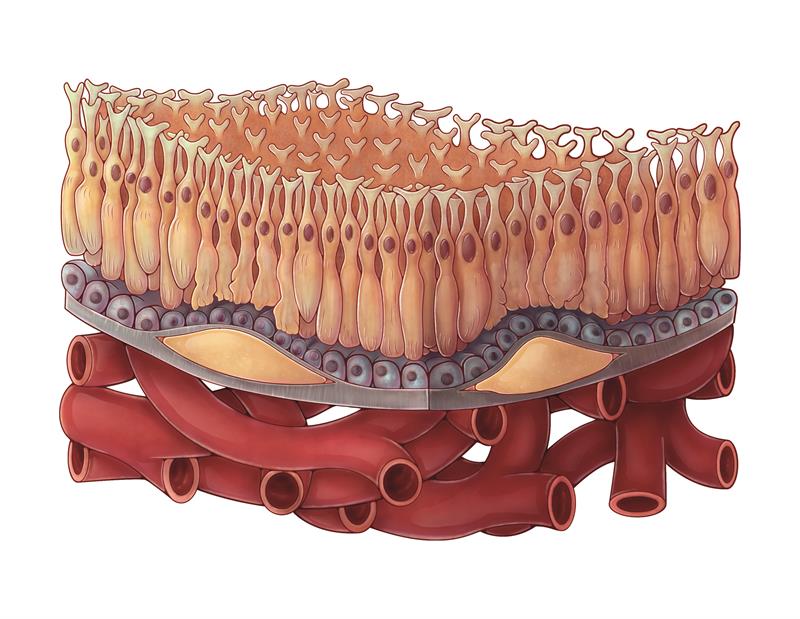

Dry AMD

Patient intervention

To maximise behavioural changes in patients with AMD, a patient intervention is required as well as an eye care practitioner intervention. Successful previous nutritional intervention studies all had nutrition messages that were limited to key nutrients or one/two simple messages to reduce cognitive demands and facilitate effective decision-making. Interventions that were successful in these studies were practical or targeted to specific needs (eg lowering sodium in hypertension). In general, behavioural changes are successful if participants were at risk of, or suffering from, a health condition; often, more serious conditions and symptoms were more motivating.9 Positive outcomes to the intervention were more likely if there was active interaction between participants and health professionals. Interventions including face-to-face meetings with participants have proved beneficial.10-12

Eggs are one of the best sources of lutein and zeaxanthin

Research has shown that people are able to cope with around 7 new concepts at one time and so new ideas need to be introduced gradually.13 The main nutrition concepts that patients with AMD need to understand are:

1 lutein and zeaxanthin are the most beneficial nutrients for AMD

2 lutein and zeaxanthin can only be obtained in the diet (are not synthesised by the body)

3 the most lutein and zeaxanthin rich foods are spinach, kale and eggs

4 the AREDS2 formula is the only clinically proven supplement

5 the AREDS2 formula has only been found to be beneficial when the disease is at a certain stage.14

Not only do eye care practitioners need to be providing correct, consistent advice to patients, but they also need to deliver this advice at a suitable time, face-to-face. When asked about how they would prefer to receive advice in a recent focus group of AMD patients, participants responded that they would only like advice given from an eye-care professional (optometrist or ophthalmologist) at a later date from the initial diagnosis. Many patients feel overwhelmed when they first receive an AMD diagnosis, and report that much of what was said in that initial appointment was not remembered. Often, patients need time to come to terms of what AMD will mean for their quality of life before beginning to investigate ways of slowing down the progression of the condition.

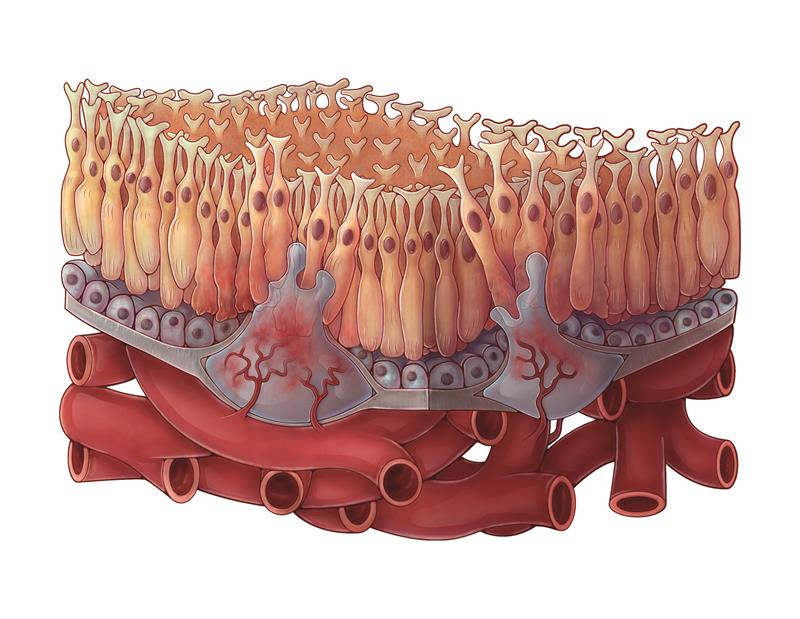

Wet AMD

Wet AMD

Participants of the focus groups also reported that written advice given to them in the form of leaflets or booklets on AMD were often vague regarding nutrition advice and supplementation, and the advice is often hidden in among other information on the condition and lifestyle. These participants would prefer more clarity rather than the often used advice of eating more leafy green vegetables. While they felt that there was no comparison for advice given vocally directly from an eye-care professional, leaflets or handouts could be used to remind patients what advice to follow if they were short and to the point and were easy to read. The Macular Society has provided useful guidelines regarding creating written material for AMD patients: documents with a large print or font size (14/16 where possible), limited italics and underling, and high contrast primary colours make it much easier for those with visual impairment to read.

In another recent study funded by the College of Optometrists, patients responded very well to a specially designed leaflet and prompt card that adhere to the Macular Society guidelines that was given alongside face-to-face nutrition advice. This response was statistically better than those that did not receive face-to-face advice and a standard booklet on AMD. Participants increased their consumption of spinach, kale and particularly eggs, and some switched their supplementation to an AREDS 2 formula, or starting taking a supplement if it was appropriate. The majority of participants reported a greater confidence in talking to their optometrist or ophthalmologist about nutrition and confidence in following their advice.15

Conclusion

Patients with AMD appear to respond well to face-to-face nutrition advice given by an eye-care professional with a simple leaflet to take home. Eye care professionals appear to be more confident and more consistent with giving correct advice by using a clinical decision-making aid, in the form of a flowchart. It is recommended that all patients with AMD receive nutritional advice in this manner – face-to-face advice, delivered at a later date than the visit where the patient is told their diagnosis (it is likely that a patient will not remember much advice at this time), with a simplified leaflet to remind the patient of the key messages.

Optometrists are uniquely placed to give nutritional advice to patients, and if ophthalmologists refer patients back to their optometrists after the diagnosis to receive the advice, patients would be at their most receptive and this would relieve some burden from busy ophthalmology departments. All optometrists need to be providing the same advice to patients (spinach, kale, eggs with the amounts needed, and supplementation if appropriate) so that patients are not confused by conflicting guidance. Providing nutritional advice in this manner can be considered gold standard eye care.

Dr Hannah Bartlett is a senior lecturer and Dr Rebekah Stevens is clinical demonstrator and doctoral researcher in the Department of Vision Science, Aston University

References

1 Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), 2013. AMD information. Retrieved from www.rnib.org.uk/eyehealth/eyeconditions/conditionsac/pages/amd.aspx.

2 Stevens, R, et al. Age-Related Macular Degeneration Patients› Awareness Of Nutritional Factors. British Journal Of Visual Impairment, 2014. 32(2): P. 77-93.

3 Turner, KMT, JM Nicholson, And MR Sanders, The Role Of Practitioner Self-Efficacy, Training, Program And Workplace Factors on the Implementation of an Evidence-Based Parenting Intervention In Primary Care. Journal Of Primary Prevention, 2011. 32(2): P. 95-112.

4 Chew, EY, et al. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (Areds2) Study Design And Baseline Characteristics (Areds2 Report Number 1). Ophthalmology, 2012. 119(11): P. 2282-2289.

5 Lyons, B, T Dunson-Strane, And F Sherman, The Joys Of Caring For Older Adults: Training Practitioners To Empower Older Adults. Journal Of Community Health, 2014. 39(3): P. 464-470.

6 Chapin, JR, G Coleman, And E Varner, Yes We Can! Improving Medical Screening For Intimate Partner Violence Through Self-Efficacy. Journal Of Injury & Violence Research, 2011. 3(1): P. 19-23.

7 Banning, M, A Review Of Clinical Decision Making: Models And Current Research. Journal Of Clinical Nursing, 2008. 17(2): P. 187-195.

8 Stevens, R, H Bartlett, And R Cooke, Evaluation Of A Clinical Decision Making Aid For Nutrition Advice In Age-Related Macular Degeneration. British Journal Of Visual Impairment, In Press.

9 Sahyoun, NR, CA Pratt, And A Anderson, Research: Perspective In Practice: Evaluation Of Nutrition Education Interventions For Older Adults: A Proposed Framework. Journal Of The American Dietetic Association, 2004. 104: P. 58-69.

10 Glasgow, RE, et al, Improving Self-Care Among Older Patients With Type Ii Diabetes: The ‘Sixty Something...’ Study. Patient Education And Counseling, 1992. 19(1): P. 61-74.

11 Van Den Arend, IJM, et al. Education Integrated Into Structured General Practice Care For Type 2 Diabetic Patients Results In Sustained Improvement Of Disease Knowledge And Self-Care. Diabetic Medicine, 2000. 17(3): P. 190-197.

12 Gilden, JL, et al. Diabetes Support Groups Improve Health-Care Of Older Diabetic-Patients. Journal Of The American Geriatrics Society, 1992. 40(2): P. 147-150.

13 Miller, GA, The Magical Number Seven, Plus Or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity For Processing Information. 1956. Psychological Review, 1994. 101(2): P. 343-352.

14 Chew, EY, et al. Lutein Plus Zeaxanthin And Omega-3 Fatty Acids For Age-Related Macular Degeneration The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (Areds2) Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama-Journal Of The American Medical Association, 2013. 309(19): p. 2005-2015.

15 Stevens, R, H Bartlett, and R Cooke. Development of nutritional educational interventions for people with age-related macular degeneration. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2017.