Previous articles in this series concentrated on the formal accountability of the optometric/optical practitioner in England. Many aspects detailed have similarities, or indeed apply in other parts of the UK, and to business registrants of the General Optical Council (GOC). This series is not intended to be a substitute for formal legal counsel and this, the final article in the series, will cover aspects of avoidance of successful litigation against optometric and optical practitioners.

Interrelated accountability of practitioners

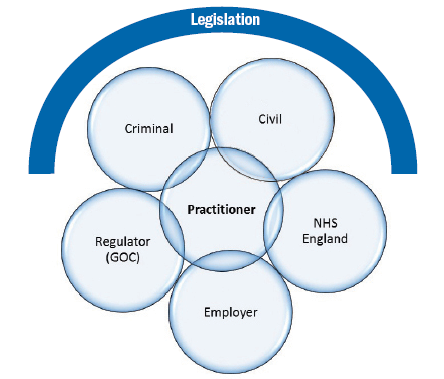

The fundamental notion to come to terms with in the first instance, is that the five key areas of practitioner accountability are interrelated and underpinned by legislation (figure 1). That is to say that if for example a practitioner was found guilty of a criminal offence (eg dishonesty) then ‘hearings’ could be held in the other four key accountability areas/authorities. The practitioner could thus find that they are removed from the relevant register by the General Optical Council, dismissed by their employer, removed by NHS England as a ‘performer’ and/or a ‘contractor’, and ordered to pay compensation as a result of a civil action in the courts. However, that is not invariably the case and it is quite possible that one or more ‘authority’ may decide differently.

Figure 1: Five key areas of practitioner interrelated accountability underpinned by legislation

This will be subject to the personal circumstances of the practitioner, the misdemeanour concerned, the standard of proof adopted by the ‘authority’, and the remit of the ‘authority’ concerned. Suffice it to say that falling foul of any one of the five key areas of accountability will, more of often than not, result in a ‘knock-on’ effect on one or more of the other ‘authorities’ of accountability.

The scope of optometric practice has expanded considerably over the years. Not so long ago, there was reluctance by optometrists to diagnose cataracts. Nowadays many optometrists have therapeutic privileges and are increasingly involved in diagnosis and management of a wide range of ocular diseases either independently or in co-management schemes with medical, optical and/or other healthcare practitioners. However, we have little information about the risk of legal action against the optometric/optical practitioner – if it has indeed altered with the expansion in the scope of practice of optometry, the increase in the practitioner population, the advent of the internet and the increasingly litigious society in the UK.

Key categories of complaints/grievances

Legal actions stem from complaints and/or patient dissatisfaction. However, information on litigation against optometrists and/or opticians is not easy to gauge, not least because most grievances do not get to court and those that are likely to, are often settled out of court.

In 2001, Timothy Cox, the then head of legal services at the Association of Optometrists (AOP) wrote in the Optometry Red Book1 that five categories dominated the list of claims upon which AOP members sought help. They included:

- Corneal grazes as a result of contact tonometry.

- Cataracts – failing to tell the patient for fear of causing alarm.

- Retinal detachments – failure to detect and/or advise appropriately.

- Glaucoma – failure to detect and refer.

- Intraocular tumours – failure to detect and refer.

However, he did not provide details of the numbers involved in each category and how many, if any, of those members that sought help from the AOP regarding the above complaints ended up being arraigned in a court of law.

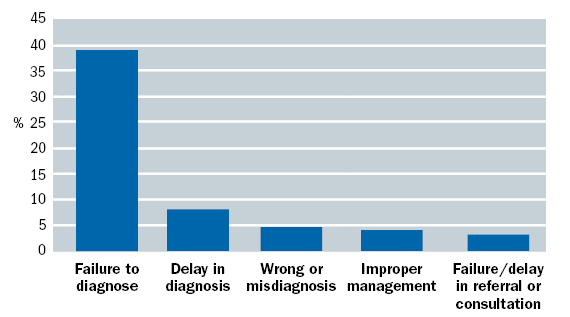

In the USA, however, there is, as a result of legislation, a national repository of information including payments for malpractice on behalf of licenced healthcare practitioners – the National Provider Data Bank (NPDB).2 An analysis of this data since the inception of the NPDB in 1990 through to 2008 was conducted in 2011 to better understand the impact of the expanding scope of practice in the USA and malpractice payments.3 Although it was suggested in 1994 that the leading cause of all malpractice claims in the USA was contact lens related,4 analysis of the NPDB data from 1991 to 2008 indicated that the most common successful litigation against an optometrist was in fact for failure to diagnose or a delay in diagnosis3 (figure 2).

Figure 2: Of the 527 allegations, five reasons accounted for two thirds of all cases

Interestingly the NPDB data analysis3 showed only a slight increase in successful litigation against optometrists over 18 years in the USA despite expansion of the scope of optometric practice, an increase in the number of licensed optometrists (11.7% up 1996 to 2008) seeing more patients, in an increasingly litigious environment for healthcare practitioners. Possible reasons as to why this might be so, include better quality of optometric care, more competitive entry into optometry courses, improved and expanded post-graduate residency programs; more rigorous licensing exams, continuing education, better risk management and of course defensive practice.3

An analysis of 50 cases where optometrists were either defendants in a civil court or appeared before the General Optical Council’s Disciplinary Committee between 1999 and 2004 revealed that the most frequent complaint was failing to detect glaucoma (15 cases), followed by failure to detect retinal detachments (13 cases).5 In the same cohort, there were failures to detect six cases of papilloedema in young adults or children, four cases of neoplasms (choroidal melanomas detected by a second optometrist) and in one case, an iris neoplasm was detected along with asymmetric intraocular pressures, but the optometrist had failed to act on the findings. Professor Woodward’s key recommendation as a result of this analysis was that ‘optometrists must practice defensive optometry’ and as the scope of optometry expands ‘more optometrists are liable to find themselves as [defendants] co-defendants in actions for clinical negligence’.5

Good optometric practice is defensible optometric practice

Defensive clinical practice is often regarded as practicing in such a way as to avert the future possibility of patient complaints and/or grievances ultimately to avoid successful litigation. Defensive clinical practice also carries the negative connotations of increased referral rates, increased follow-ups, increased diagnostic testing, and avoidance of treating/managing complex conditions/patients in community practice. However, defensive practice has a lot to commend it too including:

Staying within your own level of competency and expertise

The first rule of defensive practice and avoidance of successful litigation, which may seem obvious but must be stated, is to work within your own level of competency and expertise. This competency requirement also extends to anyone you delegate to so that you have to be satisfied that the person you are delegating to is indeed trained and competent to perform the task before you delegate. Related to this is the need to keep up-to-date with developments and the evolving and expanding scope and knowledge in optometry and related disciplines, while updating your own clinical skills regularly.

Ensuring informed consent

Competent patients are required to give of their own volition, informed consent for optometric assessment, treatment and care. Therefore they need to know what is going to be done to them or what is going to be expected of them before and during an optometric consultation along with any risks associated. There is ample material available in the form of guidance as to what makes a valid consent and the legal perspective regarding the need for it.6,7,8

Patients are also required to give consent to data being collected about them to be held by the practice in accordance with the Data Protection Act (1998) and used to provide them with relevant optometric services. To do this, again, they have to know about the data handling and data processing policies of the practice.

Consent by definition means that competent patients must have the option to accept or refuse any part of the optometric assessment, treatment or care. In the same vein, patients have the right to give or withdraw permission for the use of data about them in certain ways (eg for marketing purposes, etc); and must be able to ask questions, and have them fully answered before any consent is given.

The law does not stipulate if informed consent should be verbal or written. However, when written, it provides some evidence that consent was obtained – it is not, however, proof the consent was valid. Then there is the issue of explicit and implied consent. Explicit or express consent occurs when a competent patient freely agrees to undergo the procedure/test, having been given relevant information and having had an opportunity to ask questions.

Implied consent is deemed to have resulted when the patient adopts particular behaviours, consistent with understanding and complying with the requests of the practitioner, eg when undergoing a non-invasive procedure such as a slit-lamp exam, the patient leans forward and places their head on the chinrest to enable the examination. Implied consent is generally considered to be acceptable for non-invasive procedures. However, for any invasive procedures or any procedures that carry an increased risk, express or explicit informed consent is the norm.

To help expedite this process, practitioners could give patients information before they attend the practice regarding routine optometric procedures, and about the practices’ data handling and processing policies either as a ‘welcome pack’ of leaflets and/or by directing them to websites that provide this information. Thus when attending, patients can ask questions as necessary about the information they have been provided/accessed, acquire any further information, before consenting to the procedures, policies, etc.

Good clinical records that show dialogue with patients and sound clinical decision making are probably the best evidence of informed consent.

Making detailed contemporaneous clinical records

Lawsuits are won and lost on the evidence presented. Inadequate clinical records, lost or illegible records, unclear procedures may all lead to an inability to rebut the claimant’s case and loose an otherwise defendable case for the lack of credible evidence. The most important piece of evidence of defensive practice and avoidance of successful litigation, are good contemporaneous clinical records. They are a permanent documentation of patient contacts and state the basis for the decisions that flow from these encounters and consultations.

Diligent record keeping will pay dividends if there is a legal issue

Records are the most tangible evidence of the authors’ clinical practice, and in litigation, they may ‘illuminate’ or unfortunately ‘cast a shadow’. A very useful format for effective clinical record keeping was proposed by Weed9 when he published his proposals of the Problem Oriented Medical Record (POMR) in 1968. Subsequently he published the Subjective Objective Assessment and Plan (SOAP) approach to clinical record keeping in 1969.10 Today, the SOAP format and variations of it are used around the world by a variety of healthcare professionals and is effectively applied to optometry to structure record keeping, analysis and clinical decision making. The acronym SOAP-F, a variation developed by the author11 stands for:

S = Subjective (the patient’s perspective) – everything that the patient tells the practice/practitioner. This includes the patient’s demographics/profile data, presenting complaint(s), symptoms, and any secondary concerns, ocular history, medical history, a review of systems (necessary to establish any correlation/connection with systemic disease), social history, and family ocular and medical history.

O = Objective (the practitioner’s perspective) – the practitioner’s observations and tests: including vision, visual acuity, ocular muscle balance, pupils, motility, near point of convergence, examination of the external eye and adnexa, internal eye exam, objective and subjective refraction, accommodation, supplementary tests/data (eg Amsler, colour vision, slit lamp, fixation disparity, visual field analysis, tonometry, stereopsis, cycloplegic exam, etc). These should be recorded with details of times, instrumentation and the techniques utilised where appropriate/applicable.

A = Assessment (the analysis) – This is the practitioners’ understanding of the problem: the diagnosis(es) and differentials where appropriate for the patient, ie conclusions reached, based on the collected information from the subjective and the objective perspectives, and possible secondary problems that need to be considered.

P = Plans – The practitioner’s goals, actions, advice or counselling, etc in the best interest of patient care. This would include details of any interventions, eg therapeutic measures or interventions, dispensing of optical appliances, orthoptic exercises, additional diagnostic tests or procedures, patient (and family, if applicable) education, handouts given, referral letters sent, etc, as applicable based on the assessment.

F = Follow-up – What is done to monitor the plan, and recall/review appointments. This enables the practitioner to gauge the success or otherwise of the clinical decisions and plans made.

It is essential when making clinical records that practitioners and their practice teams should ensure their records are:

- Factual, consistent and accurate.

- Written in preferably black ink (indelible).

- Written during the patient contact time or consultation, or as soon as possible after and certainly no later than 24 hours (if the date and time differs significantly from that of when the patient contact or event occurred, then this should be clearly noted under the signature of the author, his/her printed name and position).

- Written clearly, legibly and in such a manner that they cannot be erased.

- Not altered with erasers or liquid correction fluids to delete errors. A single line should be used to cross out and cancel mistakes or errors and this should be signed and dated by the person who has made the amendment.

- Dated, timed and signed.

- Written with minimal use of abbreviations.

- Consecutive.

- Collated and stored so that loss of documentation is minimised.

- Without unnecessary jargon.

- Restricted to professional judgements on clinical/relevant matters.

The above, where appropriate, apply to records on electronic media and additionally practices that use such media and associated technology should:

- Have protocols in place to clarify access, ensure security and ensure confidentiality.

- Show the date and time of the record entry and identify the member of staff making the record entry in the absence of a signature.

- Ensure the original information can still be accessed when additions or alterations are made.

- Have a mechanism to lock down and clear screens when not in use automatically after a very short period.

Giving detailed explanation of procedures/options to patients

There are a variety of patient information leaflets, websites and other publications available covering a variety of topics for practitioners to utilise. These, if used must be up-to-date, and to comply with the Montgomery judgement,13 must indicate known contemporary alternative treatment options where appropriate, and associated known evidence based risks even if they are small or rare. As an example, patients considering contact lens wear, should be told about the actual risks of microbial keratitis with differing types of contact lenses and modalities of wear,14 and that contact lens wear is not a risk free treatment option, even if they follow practitioner’s advice and have regular check-ups, due to non-modifiable risk factors.15

Full and frank explanations can save a lot of difficulties later

Pre-exam optometric data collection routinely in practice

The collection of specific optometric data from patients prior to the commencement of the optometric examination, using non-contact tonometry, auto-refractors, electronic visual field analysers and capturing images of the fundus is increasingly common in community optometric practices – a defensive practice activity indeed. This activity is most useful when conducted on patients identified as ‘at risk’ (eg over 40 years, Afro-Caribbean over 35 years, relevant family history, relevant medical history) and as part of a complete optometric examination process.

Developing an audit within practice

Clinical audit is ‘a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change. Aspects of the structure, process and outcome of care are selected and systematically evaluated against explicit criteria. Where indicated, changes are implemented at an individual, team, or service level and further monitoring is used to confirm improvement in healthcare delivery’.16 The essence of clinical audit is continuous improvement in clinical performance brought about as a result of changes in planning, organising and managing the optometric practice, aimed at the delivering better optometric care.17

Introducing patient and customer satisfaction surveying activities

Feedback is the breakfast, not only of champions, but also of defensive practitioners.

Before beginning to collect feedback from patients and customers, be clear about what exactly you are seeking feedback on, else feedback can confuse rather than enlighten understanding of your patients and customers’ experience.

Begin with a simple individual patient satisfaction survey to be completed after each visit to the practice. It is important to ask patients and customers about their satisfaction with their interactions with practice personnel and products (eg before attending, during the visit, and after the visit).

This could be done while the patient is in the practice and posting the survey into a feedback box, or better still by encouraging them to use an electronic tablet to complete the survey in the practice at any time, or if they choose, via your website. And then always analyse the data collected and act upon the insight thus obtained.

You may periodically want to walk through the patients’ journey through the practice, and see it from their perspective to identify areas of improvement. Remember it may be useful to try this as a patient with specific needs, eg as a wheelchair user, or as someone whose first language is not English, or as one who has difficulty hearing.

Patient participation panels – a small number of patients and customers (usually between four and 15, but typically eight) could be brought together with a moderator to focus on a specific service, product or topic. These ‘focus’ groups are encouraged to discuss a topic or question to provide more qualitative data (preferences and beliefs). Although useful, their views may or may not be representative of the wider patient and customer base, so the information gleaned from such activity must be deduced and employed with caution.

Mystery shopper – using a mystery shopping service is a way of gaining an unbiased insight into the optometric service experience that the practice offers. This means that a mystery shopping service when engaged by the practice, will send in a mystery shopper unannounced on an agreed or regular basis, and provide feedback regarding their experience of attending the practice for an optometric service or product.

There are many more options for feedback, eg face-to-face presentations, via telephone, email, smart phones and by harnessing internet technology including ‘In App feedback’ options and more.

With social media taking an increasingly higher prominence in modern lives, social media ‘listening’ can be a very useful means of gathering feedback from patients and customers who may be commenting on social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn about your practices’ services and/or products. Tools like Sprout Social18 Audisense19 and Google Alert can all help take account of this feedback if used imaginatively.

Finally, any expression of dissatisfaction with any optometric services or products provided must be acted upon promptly with the intention of resolving the matter amicably. This feedback should be recorded and regularly analysed to identify trends and/or learning points for the practice as a whole.

Hopefully, as a practitioner you will never have the occasion to become answerable for your clinical practice to any of the five key authorities detailed in figure 1. However, if you are, then hopefully good defensive clinical practice will stand you in good stead against any potential litigation.

Dr Nizar K Hirji, optometrist and principal consultant, Hirji Associates, Birmingham. www.hirji.co.uk.

References

- Cox, T (2001) “Litigation by patients and others” in The Optometry Red Book, chapter 6 p91-100; Hirji, N.K.(Ed); Association of Optometrists, London,ISBN 0-9541272-0-X

- https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/ last accessed Feb 2017

- Duzack, RS and Duzack, R. (2011) Malpractice payments by optometrists: an analysis of the national practitioner database over 18 years. Optometry 82, 32-37

- Classe, JG. (1994) Avoiding liability in contact lens practice, Optometry Clinics 4 (1) 1-12

- Woodward, EG. (2006) Clinical negligence, Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 26: No 2, 215-216

- College of Optometrists http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/last accessed Feb 2017

- General Medical Council http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_index.asp last accessed Feb 2017

- Blakeney, S (2011) Consent, Optometry in Practice Volume 12 Issue 1 21 – 28

- Weed, LL. (1968) Medical records that guide and teach, NEJM, 278: 593-599

- Weed, LL. (1969) Medical records, medical education, and patient care. The problem oriented record as a basic tool, Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University,cited Savage, P. (2001) A book that changed my practice – Problem oriented medical records. BMJ, 322:275 3 Feb.

- Hirji NK. (2007) A structured approach to the Clinical Decision Making (CDM) exam administered by the College of Optometrists as part of the Final Assessment, cited McCallister G and Wickham L. Clinical Decision Making VI: Diagnosis of Visual loss; Posterior Segment, Optometry Today, 2008; p28-37, December 2000.

- Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11

- Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, Naduvilath T, Dart JK, Holden BA. (2008) The Incidence of Contact Lens-Related Microbial Keratitis in Australia, Ophthalmology Volume 115, Number 10, October 1655-1662.

- Stapleton, F et al (2007) The Epidemiology of Contact Lens Related Infiltrates, Optometry and Vision Science Vol 84, No 4, PP. 257-272.

- Research and Professional Development http://rpd-research.org.uk last accessed Feb 2017.

- Benjamin, A. (2008) Audit: how to do it in practice, BMJ 2008;336:1241-5.

- Clinical Audit, College of Optometrists http://www.college-optometrists.org/ last accessed Feb 2017.

- Sprout Socials http://sproutsocial.com. Last accessed Feb 2017.

- Audiense https://audiense.com/ last accessed Feb 2017.