Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, a group of disorders characterised by progressive cognitive decline. It is estimated that of the 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK1 more than 123,000 suffer from serious sight loss at a level that makes their day to day life very difficult due to the inability to perform basic orientation and recognition needs.2 This number is expected to quadruple by 2040.

Current Situation

Ageing is a major risk factor for both dementia and sight loss, and as the UK’s population is getting older many more people will be living with both conditions. Dementia in association with sight loss can result in isolation, risk of falls, learning difficulties and loss of independence. It also leads to anxiety, aggression and hallucination. Therefore, it would seem that vision correction and diagnosis of ocular diseases should be a priority in these patients. However, even routine eye care is often overlooked in AD individuals as their visual complaints are commonly interpreted as being entirely attributable to dementia (source: Dementia and Sight Loss Conference, 2010). In a speech to the House of Commons, Jim Shannon MP said that it is often assumed that someone with dementia ‘will not gain any benefit from sight testing and vision correction’ because they are no longer involved in any activities. But he added that if the patients are given the chance to see well, they will be more active, therefore, vision correction ‘plays an important role in supporting the well-being of a person living with dementia.’

A low level of knowledge in the general public concerning the link between vision loss and AD could also contribute to the fact that visual disabilities are not properly diagnosed and treated in AD patients. We have conducted a structured interview that included 1000 participants randomly selected from the UK general population (Gherghel et al, unpublished work). Our results show that although a high percentage of the general public recognised symptoms such as memory decline (70% of the participants) and confusion (30% of the participants) as being part of the AD’s clinical picture, only 9% of the responders believed that visual impairment and increased susceptibility to certain eye diseases were common occurrences associated with AD. It is possible that this lack of awareness leads to the fact that AD patients and their families are not actively seeking optometric or ophthalmologic advice when experiencing problems that are, in fact the result of an ocular disease. In addition to this, in the UK only very few eye care providers are properly trained to manage visual impairments in AD patients.3 Indeed, defective memory, unreliability in providing accurate answers, confusion, slow response, and low attention span, make the examination of AD patients very challenging for any professional. Therefore, vision threatening conditions may be missed as often patients with advanced dementia are often deemed ‘untestable’ by conventional means. Nevertheless, every effort should be made to increase the number of optometrists trained to treat AD patients.

The College of Optometrists (CoO), is taking great steps in creating guidelines for managing patients with AD. The Guidance for Professional Practice, has a section on ‘Examining patients with dementia or cognitive impairment.4 In addition, this organisation, in association with Alzheimer’s Society and Thomas Pocklington Trust organised a Visual Impairment and Dementia Summit (VIDem), which took place in February 2015 in London. At this event it was demonstrated that there is a high need for research in dementia and visual impairment. These three organisations have also collaborated for an application to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Programme. In this way, the Prevalence of Visual Impairment in People with Dementia (the PrOVIDe study), a cross-sectional study of people aged 60–89 years with dementia and qualitative exploration of individual, carer and professional perspectives, was born.3 The results of this study so far show a high level of visual impairment associated with dementia. This level was higher in patients living in care homes. In addition, it was also found that a very high percentage of the visual loss found in these patients is correctable with either spectacles or cataract surgery.

RNIB, Alzheimer’s Society, Thomas Pocklington Trust and Arup also took the initiative to set up a special interest group about dementia and sight loss, known as the Dementia and Sight Loss Commitee (DaSLIC), as part of VISION 2020 UK. Members also represent the CoO, General Optical Council (GOC), Royal College of Ophthalmologists, Macular Society, Blind Veterans UK, and other organisations. In January 2017, this committee has published three documents: Dementia and Low Vision Fact Sheet, Wearing Spectacles with Dementia, and Eye Examinations for People with Dementia (http://www.vision2020uk.org.uk/vision-2020-uk-dementia-sight-loss-committee-release-updated-dementia-factsheets) These documents are useful for patients, carers but also for eye-care professionals.

Vision impairment and ocular pathologies associated with AD

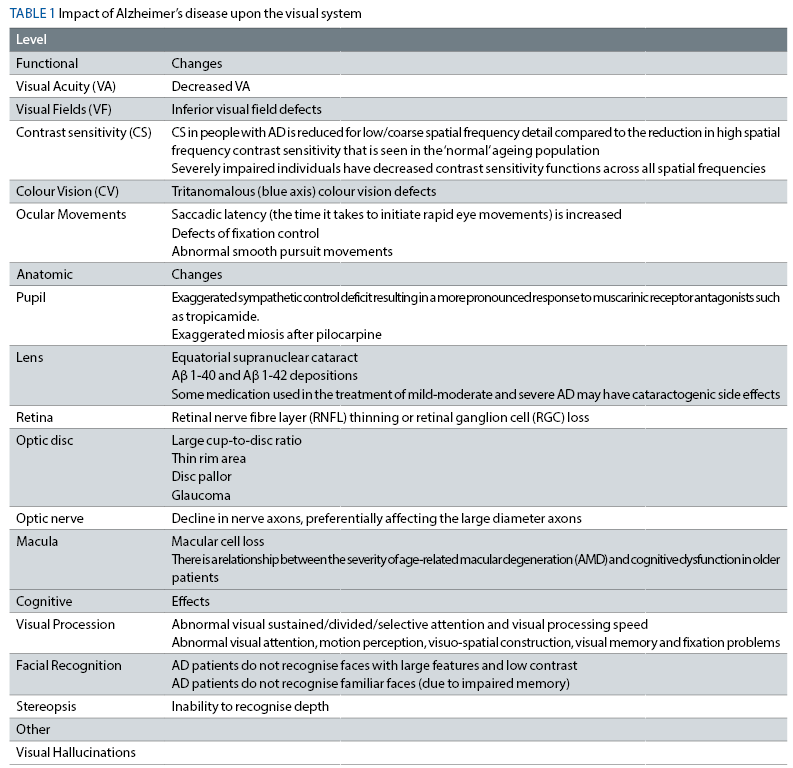

It seems that presently, important steps are made to ensure that patients with AD and other forms of dementia will benefit from early intervention to correct existent vision impairments. Optometrists should, therefore, be equipped with the theoretical and practical knowledge to diagnose and manage these occurrences. Table 1 outlines various effects on the visual system in patients suffering from AD.

A few of these abnormalities are discussed below:

1 Pupillary function and AD

Healthy older individuals show reduced pupil diameters and a possible sympathetic deficit when compared to young subjects. This sympathetic deficit appears to be exaggerated in individuals with AD. It has also been widely reported that AD patients exhibit an exaggerated mydriatic response to tropicamide (a muscarinic receptor antagonist).5,6 A possible mechanism for this may be parasympathetic disinhibition due to the loss of the noradrenergic inhibitory control of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus from the locus coeruleus.6 A prospective study followed participants who had an initial exaggerated response to mydriatics over a period of two to four years found that an exaggerated pupil response to mydriatics predicted a three-fold risk of the development of clinically significant cognitive impairment, and when there was an associated ApoE4 genotype, the risk increased to four times.5 However, the practical application of tropicamide as a diagnostic biomarker for AD has not yet been established. As it is difficult to deliver a precise known quantity of eye drop to the eye, as well as the fairly simple methods available for measuring pupil dilation there is a high number of false positives thus the test lacks sensitivity and specificity to be applied as a conclusive diagnostic tool.7,8 Interestingly miotic drops such as pilocarpine, which constrict the pupil, also have an exaggerated response, further suggesting defective innervation in AD.5,7

2 Cataracts and AD

AD patients may have a risk for different types of cataracts than age-matched individuals. Goldstein et al noted equatorial supranuclear cataracts in lenses from people with Alzheimer’s disease, but not in normal controls.9 The equatorial region of the human crystalline lens remains active even in older individuals, allowing for cell and protein transport in to the lens matrix. Higher concentrations of amyloid beta proteins were found in the aqueous of those with AD when compared to the aqueous of control participants, uptake of these proteins in the equatorial region of the lens results in the equatorial supranuclear cataracts seen. Additionally Goldstein et al hypothesised that the molecular pathological findings seen in AD overlap in the lens and the brain. They identified Aβ 1-40 and Aβ 1-42 in lenses from both AD patients and healthy controls at concentrations that were comparable to that found in the brain; and Aβ 1-40 in primary aqueous humour at concentrations comparable with cerebrospinal fluid.9 These findings suggest that the extent and type of cataract noted during eye examinations may lend itself to identification and monitoring disease progress in AD. However, at present this theory is fairly rudimental and requires further investigation.

Some medication used in the treatment of mild-moderate and severe AD may also have catarogenic side effects. Thus careful monitoring and recording of lens opacities in these patients would prove useful in disease and treatment management.5

3 AD and Glaucoma

Glaucoma, like AD, is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with ageing. When AD and glaucoma are present concurrently then the course of vision loss is usually more rapid.5,10 It has previously shown that glaucoma occurrence is significantly increased amongst patients with AD. In addition, it has been reported that patients with AD exhibit optic nerve degeneration and loss of retinal ganglion cells. However, despite numerous studies investigating the clinical and genetic relationship between these two diseases, no conclusive relationship is known. It is unclear whether the clinical association between the two diseases is due to shared risk factors or the influence of one disorder on the other.10,11 It has been observed that mean cerebrospinal fluid pressure (CSFP) is on average 33% lower in subjects with primary open-angle glaucoma than that of non-glaucomatous controls. Interestingly, it was also reported that a substantial proportion of AD patients have very low CSFP. This is of interest because it supports the theory that abnormally high trans-lamina cribrosa pressure differences (which could be as a result of high IOP, reduced CSFP or a combination of the two) could play a role in optic nerve damage seen in glaucoma. This observation may explain why patients with AD have a greater risk for developing glaucoma.10,11 In addition, vascular risk factors associated with both diseases have also been implicated.12

4 Macular degeneration and AD

A report from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) group indicated that there is a relationship between the severity of age-related macular degeneration and cognitive dysfunction in older patients.5 Brain deposits in AD are similar to drusen in that both types contain proteins such as amyloid beta,13,14 amyloid P, and apoliproprotein E (ApoE).5 Moreover, there is significant thinning of the retina of patients with AMD which is likely caused by retinal cell death; there have also been reports of notable retinal thinning in AD patients through retinal ganglion cell death at the macula.

Optometric care for AD

Although not easy, managing patients suffering from AD could be extremely rewarding for the eye care provider; improving the vision of these patients could have a dramatically positive effect on their quality of life (QoL). Communication skills are of extreme importance; even from early stages, patients suffering from dementia find it difficult to select the correct words to express their thoughts or to remember simple things. The best strategies for communicating with AD patients can be developed from nursing practice.15 In addition, the CoO’s Examining Patients with dementia or other cognitive impairment guidlelines4 also offer important information on the subject. Below are presented a few techniques that can be used in the practice:

- Present yourself and explain your role

- Always address the patient directly. Assess the patient’s needs and be patient, waiting for the patient’s answer

- Reassure the patient by voice and a gentle touch; patients suffering from AD can become easily frustrated

- Use simple questions that require either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ as an answer

- Give choices/response options

- Use the same language as the patient and ask the caregiver about the possible meanings of words/sentences

- Do one thing at a time and repeat instructions

- Don’t patronize and don’t argue with the patient. Always thank and praise the patient

- Observe and note any characteristics that indicate visual dysfunction, such as unsteady gait or abnormal head position;

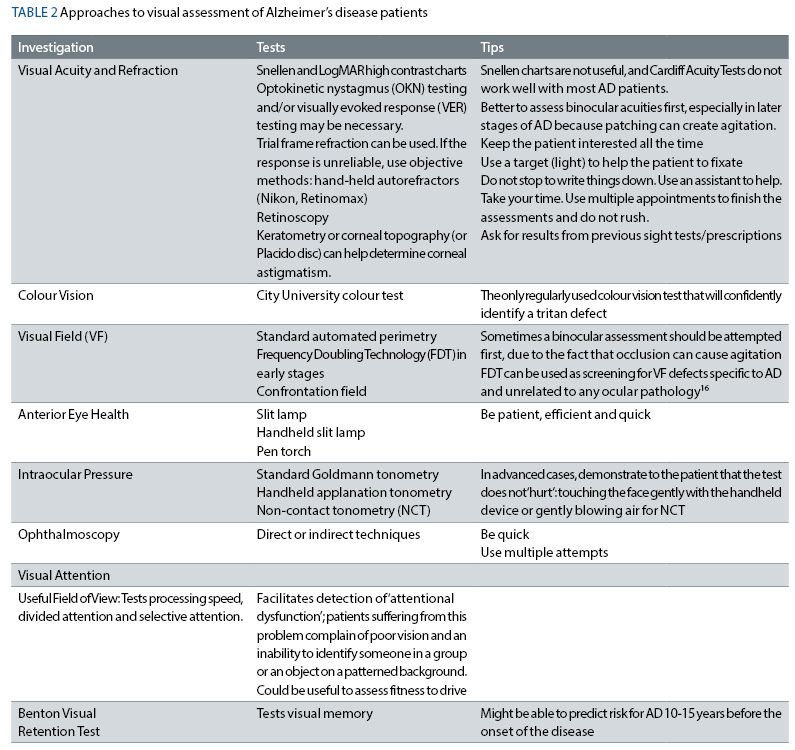

Many of the vision tests that are currently available are fairly inexpensive and more importantly can be carried out quickly and reliably by a variety of clinicians and other specifically trained individuals. Thus an effective, sensitive, appropriate and reliable battery of visual tests catering specifically for individuals with dementia may prove invaluable in terms of screening for early Alzheimer’s as well as monitoring disease

Table 2 describes the possible tests that help determine the extent of visual impairments in AD patients. The tips are adapted from a very interesting publication that deals with visual tests in mentally challenged patients (https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/adapt-and-improvise-for-the-mentally-challenged).

Before making decisions about treatment for patients who lack capacity, including AD patients, the optometrists should be aware of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 of England and Wales (in Scotland this is governed by the Adults with Incapacity Act 2000 and in Northern Ireland by common law). In addition, the practitioner should always act in the patient’s best interest.

Correcting any deficits in refraction should not be considered unnecessary in any AD patient. Caregivers should be trained to encourage the patient to wear the correction whenever necessary. However, there are reports from the caregivers showing that some patients will not wear their correction because they do not understand the reason or because of the confusion between different spectacles for distance and for near.3 Other reasons were spectacles being lost or broken with high frequency. However, it has been suggested that using high quality varifocals can increase the chance of patients wearing their correction because the quality of image is very good giving more comfort to the patient. Labelling glasses is also a good practice.

The eye-care provider could also apply other methods to increase the quality of vision in patients with AD. It has been shown that using yellow filters, which have been proven to increase reading speed and contrast sensitivity in patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and glaucoma is also beneficial in AD. In addition, cataract removal could be a good solution to improving vision. However, this procedure carries problems associated with possible coping abilities of the patients if complications occur, especially in those with challenging behaviour. However, it is proposed that once cataract is diagnosed in a dementia patient with capacity to consent, the patient should be referred immediately to the Hospital Eye Service (HES) for evaluation and treatment discussions while the patient still has capacity.17

Other ways to help AD are applying measures such as increasing colour contrast in a patient’s familiar environment. For example, it has been proven that using red coloured tableware can increase food intake by 25% and liquid intake by 85% in patients suffering from AD.18

All the above actions can have not only a very important benefit on the outcome of the AD but also on the quality of life of both patients and their caregivers. Through their clinical decision- making skills, optometrists can decide upon appropriate care of AD patients.

In addition, optometry schools should include in their programmes lectures and practical skills sessions on specific ocular healthcare-related issues in patients with AD to prepare students for than challenges that come with an ageing population.

Dr Dhoina Ghergal is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

References

1 Alzheimer’s Society 2014: Dementia report statistics. URL: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/statistics (accessed 12th October 2016)

2 Dennison C, Sheehy R, Ursell PG, 2015. Supporting people living with dementia and serious sight loss. Vision 2020 UK, Dementia and Sight Loss Interest Group. URL : http://www.careinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Dennison-Sheehy-Ursell.pdf

3 Bowen M, Edgar DF, Hancock B, Haque S, Shah R, Buchanan S, Iliffe S, Maskell S, Pickett J, Taylor J-P, O’Leary N. The Prevalence of Visual Impairment in People with Dementia (the PrOVIDe study): a cross-sectional study of people aged 60–89 years with dementia and qualitative exploration of individual, carer and professional perspectives. Health Services and Delivery Reseach Volume 4 Issue 21 JULY 2016

4 The College of Optometrists. Examining patients with dementia and other cognitive loss. http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and-performance-domain/examining-patients-with-dementia/?searchtoken=examining+patients+with+dementia. (accessed February 2017)

5 Denise A, Valenti OD. Alzheimer’s disease: Visual system review. Optometry, 2010; 81 (1): 12-21.

6 Prettyman R, Bitsios P, Szabadi E. Altered pupillary size and darkness and light reflexes in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1997;62:665-668.

7 Granholm E, Morris S, Galasko D, Shults C, Rogers E, Boris Vukov B. Tropicamide effects on pupil size and pupillary light reflexes in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2003; 47: 95–115.

8 Gomez-Tortosa E, Jimenz-Alfaro D. Pupil response to tropicamide in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;94:104-9.

9 Goldstein L, Muffat J, Cherny R, et al. Cytosolic Beta-amyloid deposition and supranuclear cataracts in lenses from people with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2003; 361:1258-1265

10 Wostyn P, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP. Alzheimer’s disease: Cerebral glaucoma? Medical Hypotheses 74, 2010: 973–977.

11 Wostyn P, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP. Alzheimer’s disease and glaucoma: Is there a causal relationship? Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:1557–1559.

12 Mroczkowska S, Benavente-Pérez A, Patel S, Qin L, Bentham, P & Gherghel, D 2014, Retinal vascular dysfunction relates to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, vol. 28, no 4, pp. 366-367

13 Dentchev TMA, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Amyloid-beta is found in drusen from some age-related macular degeneration retinas, but not in drusen from normal retinas. Molecular Vis 2003; 9:184-90.

14 Ding D, Lin J, Mace B, et al. Targeting age-related macular degeneration with Alzheimer’s disease based immunotherapies: anti-amylid beta antibody attenuates pathologies in an age-related macular degeneration mouse model. Vision Research. 2008; 48: 339–345.

15 Baker, SK. Twenty strategies for communicating with patients with dementia. Medi-Smart: Nursing Education Resourses. Nursing practice topics.

16 Velenti DA, Alzheimer’s Disease: Screening biomarkers using Frequency Doubling Technology Visual Field. ISRN Neurology 2013, 1-9

17 Hancock B, Shah R, Edgar DF, Bowen M. A proposal for a UK dementia eye care pathway. Optometry in Practice 2015 Volume 16 Issue 2 71 – 76

18 Dunne TE, Neargarder SA, Cipolloni PB, and Cronin-Golomb A. (2004) Visual contrast enhances food and liquid intake in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Nutr. 23, 533-538.