Currently in the UK (outside Wales), National Health Service (NHS) low vision services are most often provided through the hospital eye service (HES). These services include low vision assessments, and provision of optical magnifiers on a ‘permanent loan’ basis.

Electronic vision enhancement systems

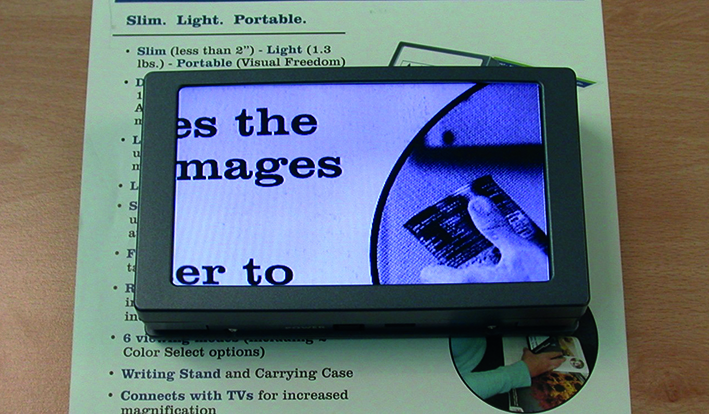

Electronic vision enhancement systems (EVES) have been in use for many years (for a review see Dickinson et al1 ), but have not been supplied through the HES. These devices consist of a camera and light source, and a screen on which to display the image. Early EVES devices were expensive and bulky, usually with desktop TV screens, (and were usually called CCTVs), and had limited acceptance. Recent technological advances have led to the development of moderately priced portable electronic vision enhancement systems (p-EVES) which resemble smartphones, and can offer potential benefits in comparison to optical magnifiers. For example, p-EVES devices can be used more naturally (binocular viewing and habitual working distance) and also incorporate many features not seen in optical magnifiers (eg variable magnification, different contrast settings and freeze frame facility). In the Low Vision Service Wales, accredited optometrists and dispensing opticians carry out low vision assessments in community practices and, in addition to optical aids, are also able to supply one p-EVES device as part of the service.2

The p-EVES study

The p-EVES Study was designed to answer the question of whether p-EVES devices offer real benefits to users for near tasks and activities, in addition to traditional optical LVAs.

The stimulus for the study was the widespread positive reaction and comments such as ‘…this (p-EVES) is my lifeline…this is absolutely magic’ from patients of Low Vision Service Wales. The aim of extending this supply to the rest of the UK was more likely if these anecdotal reports were supported by findings from a robust trial. At present there is a limited evidence base in the field of low vision rehabilitation on which to base decisions about health service commissioning and healthcare delivery.

The aim of this article is to add the information gained during The p-EVES Study to previous clinical experience, to inform prescribing guidelines that could be used in hospital low vision clinics, if a standard p-EVES device was to be made available to patients on loan. These guidelines will also be useful to community practitioners involved in commissioning or delivering enhanced services, or in advising their patients on purchasing p-EVES privately. It is worth noting that those individuals registered as sight-impaired (SI), or severely sight impaired (SSI), do not pay VAT on the purchase of electronic low vision aids.

Findings of the p-EVES study

The p-EVES Study was a prospective two-arm cross-over randomised controlled trial to determine the clinical effectiveness, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness of p-EVES devices compared to optical LVAs. This comprehensive range of outcome measures makes the study unique in the field of low vision rehabilitation. The full methodology for the p-EVES Study is described in Taylor et al.3 A total of 100 experienced optical aid users was recruited from low vision clinics at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital (MREH). Reading (for sentences in high and reduced contrast, and for paragraphs), performance of near vision activities, and device usage, were evaluated at baseline; and at the end of each study arm:

- Intervention A was existing optical aids plus p-EVES, for two months.

- Intervention B was optical aids only for two months.

A total of 82 participants completed the study. Overall, maximum reading speed for high contrast sentences was not significantly different between optical aids and p-EVES, although the critical print size and threshold print size which could be accessed with p-EVES were significantly smaller (p<0.001 in both cases), due to the higher magnification available. However, p-EVES were preferred for leisure reading by 70% of participants, and allowed longer duration of reading (p<0.001). Although the original hypothesis was that p-EVES would be more versatile, and might replace several other devices, in fact the optical aids were used for a larger number of tasks (p<0.001), and used more frequently (p<0.001). The p-EVES is therefore an extra device in the clinician’s armoury, in that it complements rather than replaces other aids for near vision. These results are reported in detail in Taylor et al.4

During the study arm when they had a p-EVES device, participants were able to carry out more tasks independently (p<0.001) (thus saving carer time) and reported less difficulty with a range of near vision activities (p<0.001). The p-EVES are more expensive than existing optical magnifiers, so the VisQoL questionnaire,5 was used to measure vision-related quality of life and to estimate the cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained for the p-EVES compared to optical LVAs. The health economics analysis is reported in detail in Bray et al.6 The QALY is a well-established outcome measure in health economics which is used to aggregate the quantity and quality of life experienced in a given health state. Based on current retail prices for p-EVES, the cost per QALY was much higher than the NICE threshold of £20,000 to £30,000, but analyses demonstrated that the p-EVES interventions could become cost-effective if a device cost around £150 could be achieved. It is possible that manufacturers would be able to reduce the costs to this level for a basic device, especially if this was to be supplied in large numbers. (This has been achieved for the one p-EVES model – currently the Visum – used in Low Vision Service Wales). It is important to note that this device would need to have equivalent features, and quality, to the devices used in the p-EVES Study if similar clinical effectiveness was to be achieved.

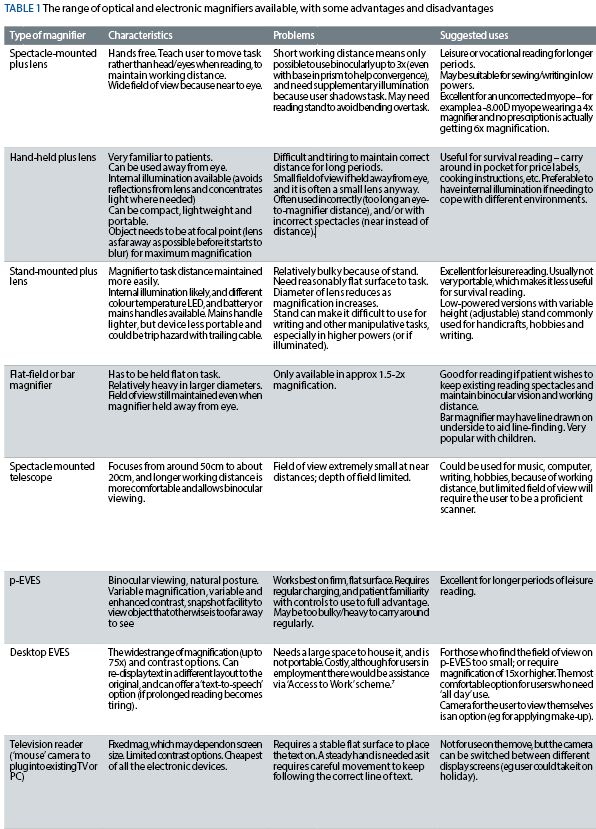

The range of optical and electronic magnifiers available for near vision

A typical selection of the optical aids available in a clinic is described in table 1: a typical ‘entry-level’ p-EVES and two types of large-screen/desktop EVES device have been included for comparison. There are also vision enhancement1 and sensory substitution apps for smartphones and tablets which can perform some of the same functions, but will not be considered here.

When would p-EVES be useful?

Visual criteria for p-EVES

The inclusion criteria for the p-EVES Study were VA of 0.7 logMAR (6/30 Snellen) or worse and/or log contrast sensitivity of 1.20 or worse (in the better eye), based on clinical experience. This distance VA suggests a near magnification for comfortable reading of newsprint (N8; threshold acuity N4) at 25cm, of 2.5x. For impairment less severe than this, patients will often find that, even on the lowest magnification setting, the text that they are reading with a p-EVES will appear larger than they require, and they are more likely to manage well with optical aids and/or large print materials.

Distance VA was not predictive of the outcome measures in the trial, although those with better near VA read significantly faster. Approximately 40% of participants were registered as Severely Sight Impaired, but the data did not suggest that poor acuity was a limiting factor in successful use of p-EVES.

Patients with <1.20 log contrast sensitivity (measured using the Pelli-Robson chart or Mars Contrast Letter Test – further information can be found at www.marsperceptrix.com)8 usually need illuminated magnifiers in order to optimise contrast.

This would suggest that these individuals may find p-EVES particularly useful due to the enhanced contrast settings, although this moderately reduced contrast sensitivity on its own is not enough to recommend a p-EVES device. For severe contrast sensitivity loss (<0.5 log contrast sensitivity), clinical experience suggests that the p-EVES would be the preferred choice, regardless of the magnification requirement.

The presence of a central scotoma and eccentric viewing can reduce reading speed considerably, even if magnification is adequate. The Amsler grid is notoriously insensitive in revealing missing areas in the visual field,9 and is not helpful in identifying this loss in clinical situations. The p-EVES Study used the California Central Visual Field Test (CCVFT) which allows the clinician to plot the patient’s central scotoma by flashing stimuli from a laser pen.10 Missed target locations can be recorded on the testing sheet and the scotoma found can be explained to the patient. Based on the results of the p-EVES Study, participants with a central scotoma were more likely to use their p-EVES device frequently. This is probably because those who do not have a central scotoma are more likely to manage well with optical aids, and may not benefit so much from a p-EVES device.

Near vision activities criteria for p-EVES

It is important firstly to establish exactly what a patient needs help with. It is necessary to find out what the patient can and cannot do (their ‘activity limitations’11), and which of these difficulties are significant to them.

Considering the range of everyday tasks which patients identify, and the characteristics of the aids already discussed above, the practitioner can identify suitable devices/strategies for the patient. Sometimes a task can only be achieved with assistance, or is always performed by someone else, but this limitation is not inevitably a problem. If an individual is happy to receive help to carry out a task, it is not appropriate to try to persuade them that they would find an aid valuable – all aids require motivation and practice to use, and this person will not have enough of either.

There are many ways in which to conduct this conversation with the patient, and the questions may need a different emphasis to reflect the different priorities of, for example, an older retired person, compared to someone in work or school. General topics to be covered include mobility and use of transportation; use of phones and computers; reading, writing and communication; shopping and household chores; education, employment, hobbies and interests. (There are also questions which do not specifically relate to visual tasks, activities and lifestyle: for example, with regard to performance in different lighting levels, or to visual phenomena such as glare, scotomas or hallucinations).

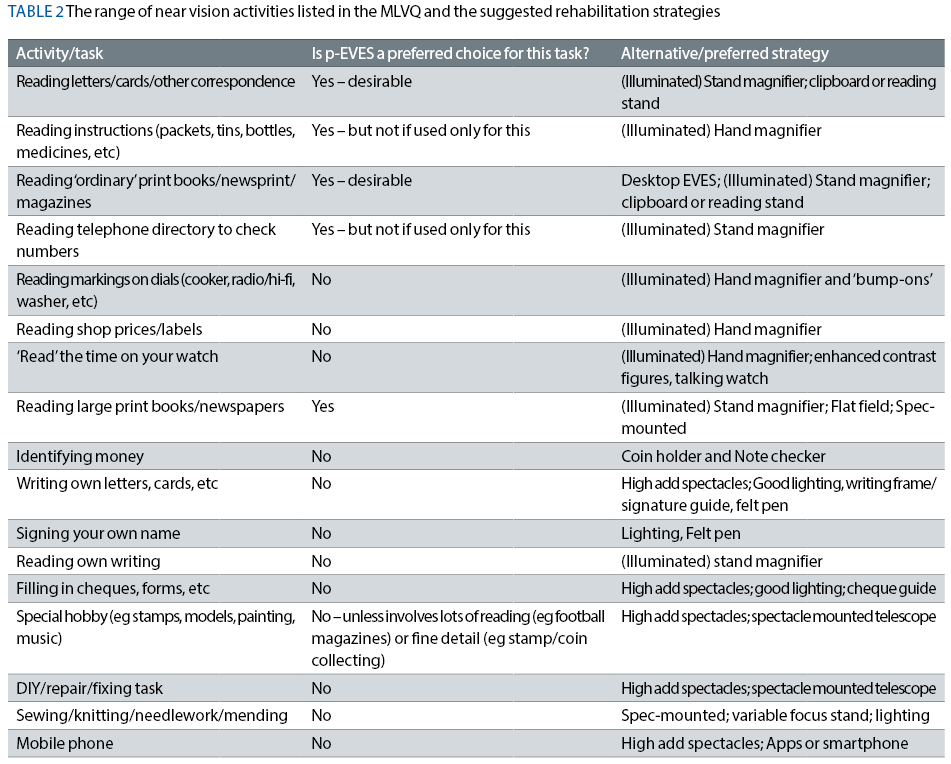

In the context of the p-EVES Study, the first part of the Manchester Low Vision Questionnaire (MLVQ)12 was a useful tool for establishing the range of everyday tasks undertaken. (This review just considers near vision tasks, so distance tasks from the MLVQ are not shown). These are listed in table 2 with guidelines for when p-EVES devices may be considered (assuming the visual criteria, suggested above, are also met). Sensory substitution devices are recommended for some tasks, and are available online from the RNIB shop (www.rnib.org.uk) or from local resource centres.

As p-EVES are not indicated for those with low magnification needs (2x to 3x), and many patients have not previously had the opportunity to try electronic aids, many potential p-EVES users will have used, and be familiar with optical aids: they may indeed be happy with their current devices and have no desire to change them. However, there are various complaints that might be raised by optical aid users, especially those with high powered magnifiers. User reports which might suggest that it would be beneficial to demonstrate p-EVES are:

1. Field of view too limited, even when aid being used with an appropriate eye-to-magnifier distance.

2a. Close working distance/awkward posture limits duration of use

and/or

2b. Wants/needs to carry out extended reading tasks (>15 minutes at a time).

3. Able to carry out survival reading, but leisure reading not possible.

The disadvantages identified with p-EVES use tend to be somewhat different, and should be discussed with potential users. Lack of portability, bulkiness/weight of device, and the time taken to select the optimum viewing options, are typical difficulties reported. This relates to the finding that p-EVES devices were mainly useful for leisure or vocational reading for longer periods, and this is the major indication for p-EVES. It obviously only applies to users who rely on printed materials: some individuals may be accustomed to accessing news online, or to using electronic books/documents. Patients are more likely to prefer optical aids for spot/survival near vision tasks, because they can be operated more quickly, and because they are easier to carry around. A patient’s motivation for change needs to be assessed as the p-EVES devices are slightly more complex devices to operate than most optical aids (there are more display options) so it is best if the patient is keen to go home and immediately start to become familiar with its use, and then plans to use it regularly (to maintain familiarity). Support at home (by friends or family) is also a positive indication: this has been linked previously to better adaptation to vision loss and use of aids, because of the encouragement which is available to the individual.13

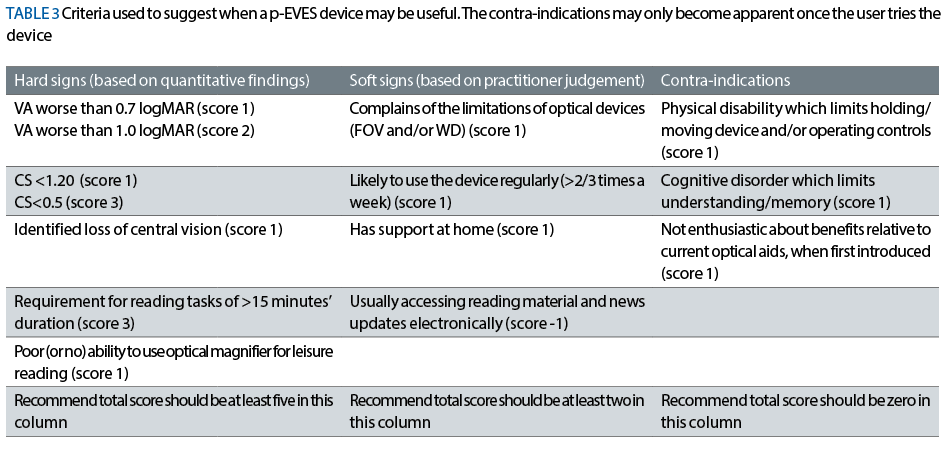

Table 3 summarises the indications for p-EVES based on the clinical and research experience obtained during the p-EVES Study. These have been given a subjective ‘score’ to help the practitioner determine whether a p-EVES is likely to be useful for that particular patient, with a higher score suggesting a better prognosis.

Task-based practice

To instruct the patient in using the p-EVES it is helpful for them to carry out different tasks whilst being observed, in order to demonstrate, and be sure they can operate, the various features of the device. This process was found to take between five and 30 minutes.

Task-based practice is best done sitting at a table so the practitioner can demonstrate the best posture to use when reading extended text for long periods of time. The patient should be wearing the appropriate (near) spectacle correction for the task.

Firstly, it is essential to demonstrate the layout of the buttons or switches, remembering to draw attention to any tactile features on the device.

The magnification settings can be demonstrated using black and white text, eg a newspaper. They need to be instructed that when switching the device on it will not automatically default to the most appropriate magnification setting: they will need to select it, and they may require different settings for different tasks.

Due to the large number of contrast/colour settings, a systematic approach to demonstrating these features is necessary. Firstly, demonstrate the full colour mode. This is an essential mode when reading brightly coloured or glossy packaging as the enhanced modes can cause some information to be faded. Using a brightly coloured food packet or similar, show the patient the correct posture and handling of the device and go to the desired magnification for the task, and demonstrate the full colour and then enhanced black and white settings. These settings are not particularly user-friendly, since it is necessary to scroll through all the options in sequence – it is not possible to ‘go back one’. It will therefore be useful to encourage the patient to count how many ‘presses’ it requires to change between full colour and black-and-white, and then to encourage them to use the same method to reach any preferred contrast setting(s) they identify from the default.

Next it is useful to show them how to use the p-EVES hand-held to demonstrate spot/survival reading, ie instructions on packets. Following this step, demonstrate the snapshot/freeze frame function. Using food packets lined up as if they were on a supermarket shelf that is out of reach, show the patient how to take a photo of the packets with arms outstretched, and then how to magnify the image taken when subsequently viewing the screen from a closer distance.

The patient will also need to know how to charge the device, and it is recommended to charge it overnight as the charge runs out after approximately two hours of use.

Basic large print instructions should be provided in addition to the manufacturer’s instructions to simplify the steps for the patient: this information would be useful in the form of a single sheet with a schematic diagram of the device, with the controls labelled in large print. Figure 1 shows an example of such an instruction sheet.

An audio version, or an online tool such as a YouTube video, would be a useful addition: this could be uploaded by the manufacturer, or by an interested practitioner if they were regularly recommending the same device. If the patient has a break in using the device, for example if they go away on holiday, or into hospital, these extra instructions will be vital as they may forget the task-based practice. These instructions should also include contact details for the clinic in case the patient has problems using the p-EVES, and for the manufacturer in case the device is faulty.

Follow up

At Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, a follow up telephone service has been successfully implemented within the low vision clinic to follow up after prescription of optical aids. Usually this is at four weeks and if problems are identified, the patient is booked back into the clinic at the earliest opportunity.

In the case of p-EVES, a telephone follow-up after one to two weeks with the device is recommended. This call will help to establish any technical difficulties with the device, or with operating the controls. If problems are identified the patient can be booked in for re-instruction. The most useful questions to ask the patient at this early stage are:

Do you experience any of the following difficulties with the device/your magnifiers?

- Technical problems, difficulties operating or apparent movement/smearing of the image.

- Does not help vision enough.

- Weight.

- Too small a screen/field of view.

If a patient is experiencing any of these issues, they should be asked to return for re-instruction, or to consider their other options.

Currently in Manchester Royal Eye Hospital low vision clinics, patients undergo their initial assessment and optical aids are supplied. Where the patient meets the criteria described above, the concept of electronic magnifiers is introduced to the patient and if they are interested they will be booked into the Electronic Low Vision Enhancement Service (ELVES) clinic. At these appointments, patients are shown a range of electronic devices including various types of p-EVES and also the less portable devices such as desktop CCTVs and the television reader. Patients are aware going into this clinic that the devices shown are not available on loan in the same way that their optical aids are, and would have to be purchased from the suppliers.

If an ‘entry-level’ p-EVES device was available ‘on loan’ through the NHS, there would still be those patients who required more specialised options. An ELVES clinic could still serve a useful purpose in demonstrating these devices such as the seven-inch screen p-EVES, television reader or CCTV.

Case studies

The case studies below show how the scoring system described above could be applied with some example patients.

Case study 1

Px demographics

Gender: Female

Age: 93 years

Diagnosis: Dry AMD, registered SI

Case history

Lives alone. Struggles to read print magazines for prolonged periods and leaves correspondence for family members who visit once a week. Worries about losing independence and would like to do tasks for herself. Currently has illuminated stand magnifier 16D/4x and illuminated hand magnifier 16D/4x.

MLVQ: Uses stand mag at home and hand mag in shops. Field of view of both optical aids reported as a problem. Can use both for up to five minutes only.

Visual Assessment:

Scores based on hard and soft signs: Hard signs=6, soft signs=2, contraindications=0. May find p-EVES useful.

Low vision aids issued: eMAG 43 (p-EVES). To aid with long periods of reading. Task based practice carried out in low vision clinic.

Telephone follow up at 1 week: Using two to five times a day, only using at home, rated as ‘very easy’ to use. Uses optical hand magnifier when outside of the house.

Plan: Continue with these low vision aids for now. Given clinic’s contact details if experiencing any problems in the future.

Case study 2

Px demographics

Gender: Male

Age: 92 years

Diagnosis: Wet AMD, registered SI.

Case History

Lives with spouse. Always accompanied when out. Currently has Illuminated hand magnifier 10D/2.5x. Slight hand tremor when using magnifier.

MLVQ: Uses optical aid for all tasks including correspondence, spot reading and occasional leisure reading (newspaper), no issues reported.

Visual Assessment:

Scores based on hard and soft signs: Hard signs=1, soft signs=2, contraindications=0. No p-EVES indicated.

Low vision aids issued: Illuminated stand magnifier 10D/2.5x to use for leisure reading at home. Continue with own hand magnifier when spot/survival reading.

Telephone follow up at 4 weeks: No problems reported with either magnifier. Using stand magnifier at home, reminded to wear near spectacles when using this device. Hand magnifier in use for occasional DIY tasks around the home, and for shopping.

Plan: Continue with these low vision aids and can attend low vision clinic in the future if the vision changes.

Case study 3

Px demographics:

Gender: Male

Age: 45 years

Diagnosis: Stargardt’s disease, registered SSI

Case history

Lives with spouse. Employed full time. Very independent, goes out alone, uses symbol cane. Has illuminated hand magnifier 39D/10x.

MLVQ:

Uses optical aid for the majority of spot/survival tasks. Cannot use it for leisure reading, finds field of view too small.

Visual assessment:

Scores based on hard and soft signs: Hard signs=10, soft signs=3, contraindications=0. May find p-EVES useful.

Low vision aids issued: Compact 4HD (p-EVES). Task based practice carried out in low vision clinic.

Telephone follow up at 1 week: Using around 10 times a day, both at home and when shopping. Would be interested in a device with a bigger field of view.

Plan: Book patient into the ELVES clinic for demonstration of a desktop CCTV and a larger screen version of his p-EVES device.

Possible future NHS supply of p-EVES

The findings of the p-EVES Study are sufficiently positive to support a bid to commissioners of services to introduce p-EVES supply as a potential service development in NHS clinics throughout the UK, so they can meet the requirements of the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment for Eye Care and Sight Loss Services.14

Rachel Bambrick and Dr Robert Harper are based at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester. Professor Christine Dickinson is based at the Division of Pharmacy and Optometry, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester. John Taylor is based in the School of Health Professions, Faculty of Health and Human Sciences, Plymouth University

Acknowledgements

- This publication presents independent research funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0211-24105). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

- We thank Bierley.com and Optelec for permission to use photographs of their products.

References

- Dickinson C, Hernandez Trillo A and Gridley A (2017) Electronic Vision Enhancement for Low Vision Optometry in Practice (to be published in May)

- Charlton M, Jenkins DR, Rhodes C, et al. (2011) The Welsh Low Vision Service- a summary. Optometry in Practice 12(1): 29-38.

- Taylor J, Bambrick R, Dutton M et al (2014) The p-EVES study design and methodology: a randomised controlled trial to compare portable electronic vision enhancement systems (p-EVES) to optical magnifiers for near vision activities in visual impairment. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt 34: 558–572

- Taylor J, Bambrick R, Brand A, et al (2017) Comparing portable electronic vision enhancement systems (p-EVES) to optical magnifiers for performance of near vision activities: Results of a randomised crossover trial Ophthalmic Physiol Opt (in press)

- Peacock S, Misajon R, Lezzi A et al (2008) Vision and quality of life: development of methods for the VisQoL vision-related utility instrument. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 15: 218-223

- Bray N, Brand A, Taylor J, et al (2016) Portable-electronic vision enhancement systems (p-EVES) in comparison to optical magnifiers for near vision activities in visual impairment: Economic evaluation alongside a randomised crossover trial Acta Ophthalmologica doi/10.1111/aos.13255

- Access to Work (2016) Overview of scheme Available at www.gov.uk/access-to-work/overview

- Haymes SA, Roberts KF, Cruess AF et al (2006) The letter contrast sensitivity test: clinical evaluation of a new design Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 2739-2745

- Crossland M and Rubin G (2007) The Amsler chart: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence Br J Ophthalmol 91: 391-393

- Cole RJ (2008) Modifications to the Fletcher Central Field Test for patients with low vision. J. Visual Impairment & Blindness 102(10): 659

- WHO (2001) International Classification of Functioning , Disability and Health Available at http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ Accessed 15-05-2016

- Harper R, Doorduyn K, Reeves B, Slater L (1999) Evaluating the outcomes of low vision rehabilitation. Ophthal. Physiol. Opt.19 (1): 3-11.

- Watson GR, de l’Aune W, Stelmack J et al. (1997) National survey of the impact of low vision device use among veterans. Optom Vis Sci 74: 249-259

- UK Vision Strategy (2014) Outcome 2 Available at: www.vision2020uk.org.uk/UKVisionstrategy/page.asp?section=288§ionTitle=Outcome+2