Pigmented fundus lesions are often noted on routine optometric examination. They range from lumps and bumps that are perfectly harmless, where the patient remains asymptomatic throughout their life, to sight- and life-threatening conditions that are cause for urgent referral. They are also often difficult to discern from each other because of the variety of types seen and there are many differentiating characteristics.

It is therefore imperative that optometrists working in primary care have a sound understanding of their differential diagnoses. In the first article (Optician 15.09.17) we considered lesions affecting the retinal pigment epithelium and choroidal naevi. In this second article we will focus upon choroidal melanoma and other neoplastic or apparently neoplastic conditions.

Choroidal melanoma

Choroidal melanomas are the most common intraocular neoplasms in adults, but thankfully are still relatively rare. The occurrence of uveal melanoma overall is low, with an estimated worldwide incidence of 7,095 new cases per year, with over 80% of these being choroidal melanomas.34 Early diagnosis of choroidal melanoma is critical, as size is the most important prognostic factor for mortality.35

While some patients are asymptomatic, the commonest symptoms are photopsia (often described as a ‘ball of light’ or ‘fireball’ travelling across the vision), floaters, visual field loss and reduced visual acuity. Occasionally, uveal melanomas may cause secondary glaucoma, inflammation or necrosis, and in these instances patients may experience pain.36 Extrascleral extension has been reported in up to 15% of cases,37 and in these instances patients may present with an externally visible lesion.

Risk factors for development of choroidal melanomas may be host (patient-related) or environmental (external factors). Of the host risk factors, light skin colour, light coloured irides (blue or grey) and a tendency to sunburn or an inability to tan are major risk factors.38 This may be explained by these patients having a lower number of melanocytes within their epidermis and uvea, as discussed in the first article.

Ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis is also a risk factor, and approximately one in 400 patients with this condition, otherwise known as Naevus of Ota, develop uveal melanoma in their lifetime.39 One in 8,845 Caucasian patients with a choroidal naevus will develop a choroidal melanoma.31 Environmental risk factors (including arc welding and chronic UV exposure) have been reported as increasing the risk of choroidal melanoma.40

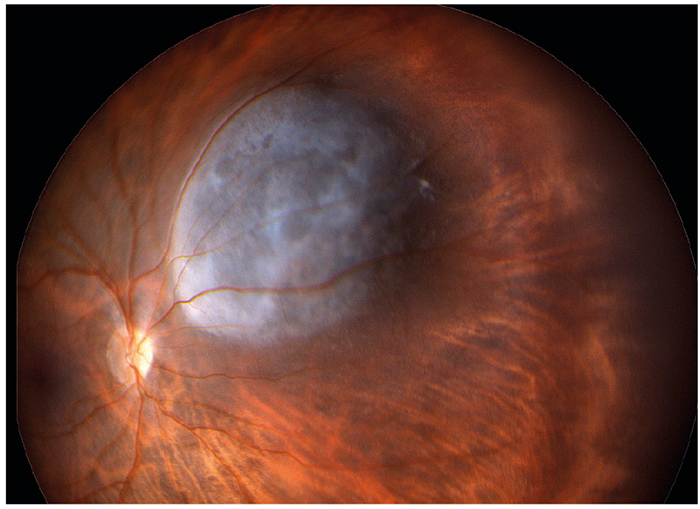

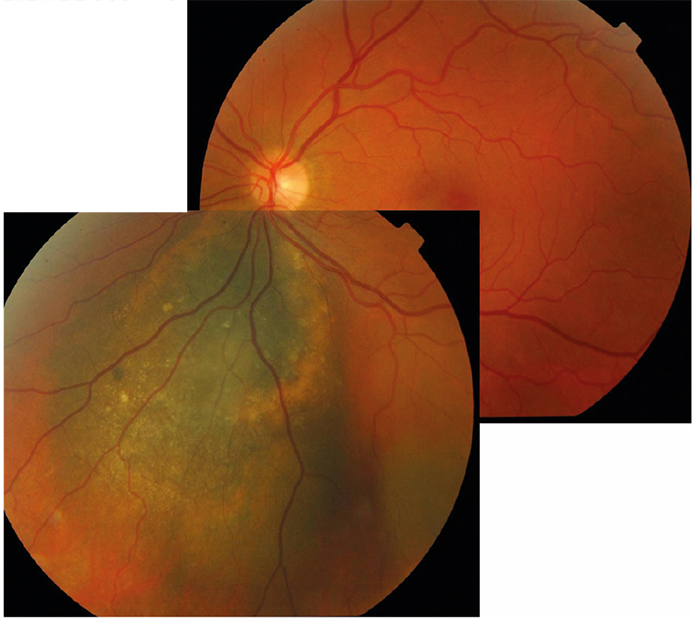

Choroidal melanomas are usually seen as raised (thicker than 2mm)26 and pigmented fundus lesions, although they are amelanotic in 15% of cases. Their margins are often unclear and they are generally dome shaped (75%), but can be mushroom/‘collar stud’ shaped (20%) or diffuse/flat (5%).41

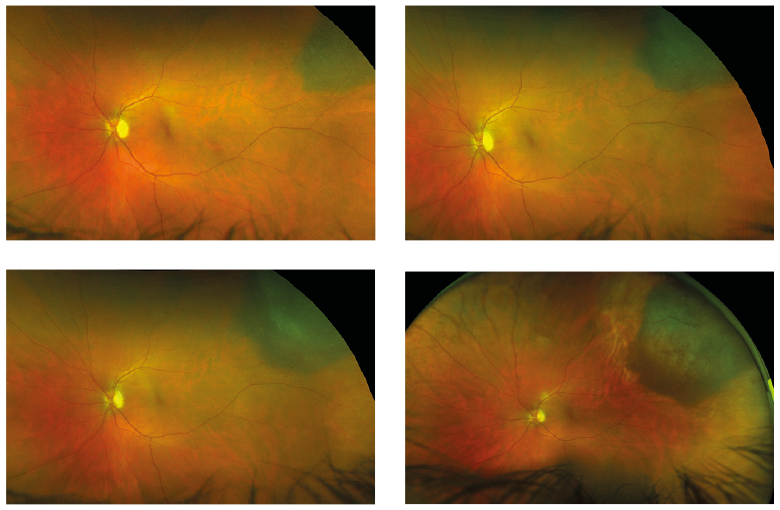

There may also be overlying sub-retinal fluid and/or orange lipofuscin pigment. Melanoma should be considered in any growing pigmented fundus lesions, particularly in those growing rapidly.25 Figures 1 to 6 show a range of choroidal melanomas of varying presentation.

Figure 1: Ultrawide field view of developing choroidal melanoma (courtesy of Optos)

Much like the useful TFSOM-UHHD mnemonic discussed in the first article in this series, the ‘MELANOMA’ mnemonic has been developed to aid the practitioner in detecting features suggestive of choroidal melanoma. If a tumour has none of these features there is a 4% chance of growth in five years, one feature gives a 38% chance of growth and two or more features leads to a 50% chance of growth and the diagnosis is likely to be choroidal melanoma:42

- Melanoma visible externally (extrascleral extension)

- Eccentric visual phenomena (eg photopsia, floaters and/or scotoma)

- Lens abnormality (eg cataract and/or new or increasing astigmatic refraction)

- Afferent pupillary defect (usually caused by retinal detachment)

- No improvement with optical correction (ie blurring or metamorphopsia with optical correction)

- • Ocular hypertension (especially unilateral hypertension)

- Melanocytosis

- Asymmetrical episcleral vessels

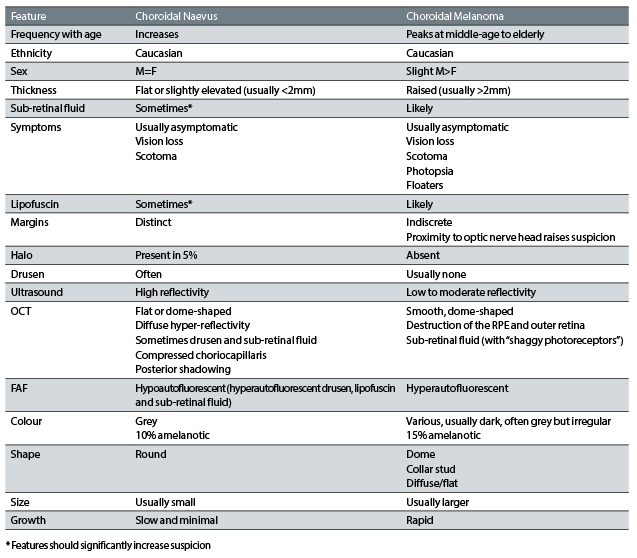

A summary of the differences between choroidal naevus and melanoma is shown in table 1.

Table 1: A comparative summary of the features of choroidal naevi and melanomas

While ophthalmoscopic examination remains the cornerstone of clinical examination of patients with suspect choroidal melanoma, other ancillary tests including ultrasound, fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), indocyanine green angiography and OCT may be beneficial. Lesions are not typically biopsied due to risks of complications, and a high likelihood of inadequate sampling.36

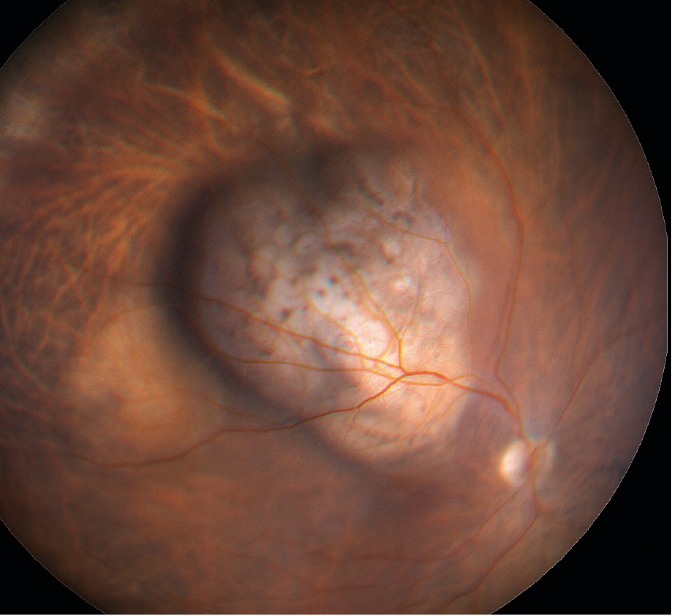

Figure 2: Large domed elevated melanoma

On OCT, melanomas appear as smooth, dome shaped lesions13 with some destruction of the RPE and outer retina.29 Sub-retinal fluid often features so-called ‘shaggy photoreceptors’ on its underside (thought to comprise oedematous photoreceptors or macrophages with lipofuscin). OCT is certainly very useful in detecting sub-retinal fluid and subtle growth of lesions.13 On fundus autofluorescence (FAF), melanomas tend to be hyperautofluorescent due to RPE lipofuscin accumulation. Indeed, detection of subtler cases of lipofuscin can be greatly enhanced by the use of FAF.30

Figure 3: Large elevated melanoma with pigmentary hyperplasia

Any suspicion of choroidal melanoma by an eye care practitioner should indicate urgent referral to an ophthalmologist. After being seen by a general ophthalmologist, current Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines43 state that the following cases should be referred to a designated Centre of Excellence for adult ocular oncology (currently in Liverpool, London, Sheffield and Glasgow).

Figure 4: Melanoma causing clear vascular deviation

Requirement for urgent referral 1; any melanocytic choroidal tumour with one of the following:

- Thickness greater than 2mm

- Collar stud shape

- Documented growth

Requirement for urgent referral 2; any melanocytic choroidal tumour with two or more of the following:

- Thickness greater than 1.5mm

- Orange pigment

- Serous retinal detachment

- Symptoms

- A primary intraocular tumour other than a naevus

- A metastatic intraocular tumour

- An intraocular lymphoma

The American Joint Committee on Cancer’s ‘Cancer Staging Manual’ provides a framework for classification of choroidal melanoma, and categorises them by thickness and basal diameter. It also sub-classifies them by whether there is ciliary body involvement or extrascleral extension.44 The rates of metastasis at 10 years increased for each category (15% in T1, the lowest category, to 63% in T4, the highest), and between each category the rate of death doubles.36

Figure 5: Pale domed melanoma

Management of melanoma depends on size, location and patient factors such as age, systemic disease and patient wishes. The commonest treatments include enucleation and focal radiotherapy. Irradiation is usually by Ruthenium-106 or Iodine-125 plaque radiotherapy, and is usually reserved for melanomas smaller than 18mm diameter and 12mm thickness. Radiotherapy is also considered in larger lesions but patients are counselled on potential side effects and the threat of melanoma recurrence. Enucleation is the usual course of action in larger tumours especially those with extrascleral extension or involving the ONH. Other treatments such as transpupillary thermotherapy and laser photocoagulation are sometimes considered as alternatives or adjunctive therapy. Exenteration is required in advanced cases with extrascleral extension.45

Figure 6: Mosaic image showing large spread melanoma with overlying lipofuscin scatter

More than 50% of patients with uveal melanoma develop metastases, the liver being the most common initial site.46 Various factors increase the risk of metastasis including diffuse shape, large size, ocular melanocytosis, ciliary body involvement and extraoscleral extension,36 the latter has been reported to increase mortality by three times.37 Patients often go through regular systemic evaluation including physical examination, liver function tests, along with various radiological investigations, including chest x-ray and liver MRI or ultrasound. Patients are now offered genetic testing to aid prognosis.45 Metastatic disease holds a poor prognosis.46

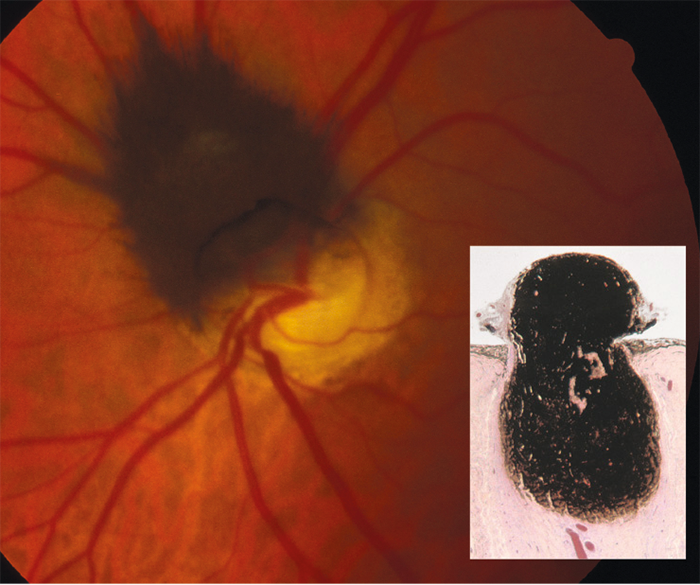

Melanocytoma

Melanocytomas are benign unilateral, dark brown or black lesions typically located at the optic nerve head (figure 7), but are occasionally seen in extrapapillary locations within the uveal tract. They have been reported as more common in black individuals, but this is disputed in the literature.47 They do not usually cause any symptoms, however 26% display minor visual problems because of sub-retinal fluid or retinal exudation, and up to 30% display a relative afferent pupillary defect due to optic nerve compression by neoplastic cells.48 Rarely they may cause severe vision loss through vascular occlusion or tumour necrosis.49

Figure 7: Melanocytoma by ophthalmoscopy and in cross section (inset)

In reality, melanocytomas are a form of naevus and, histologically, they appear as uniform, highly pigmented plump polyhedral naevus cells.24 Malignancy from melanocytoma is unusual (possibly fewer than 2% of cases),48 though, care should be taken to confirm it from its differential diagnoses. These patients should be monitored annually, and if there is any sign of malignant transformation, enucleation is required.48

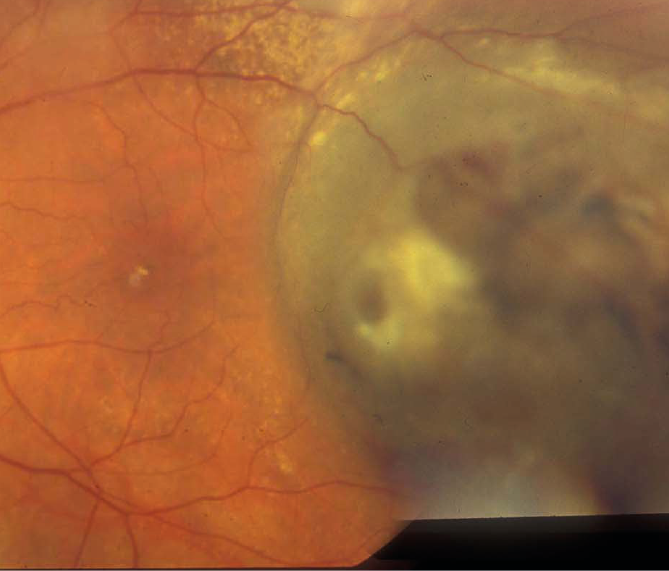

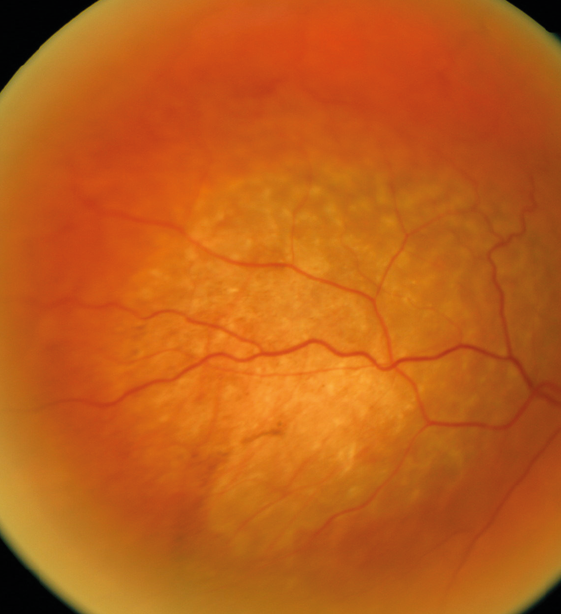

Choroidal metastases

Uveal metastases are usually choroidal and most frequently from the breast or lung. They are sometimes solitary and unilateral (figure 8) but usually multiple, bilateral yellowish lesions. Sometimes they are fully pigmented, but more typically they are yellowish with a stippled pigmented surface. Treatment depends on the patient’s systemic health status, and involves monitoring the tumours if poor or other treatments such as plaque radiotherapy or even intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy if good.50

Figure 8: Raised pale neoplasm of metastatic origin

Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation

Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP) is a reasonably rare condition occurring in patients with a systemic carcinoma. Discovery may precede diagnosis of the systemic condition, which is often gynaecological, but sometimes in the pancreas, lung, gall bladder or bowel. There are five key features associated with BDUMP: multiple small (less than 2mm) pigmented uveal melanocytic lesions, multiple round red patches within the RPE, multifocal areas of hyperfluorescence on FFA, exudative retinal detachment and rapid-onset cataracts. The prognosis in this condition is poor, and even if treatment of the systemic carcinoma is successful, lesions may continue to grow and even metastasize.51

Peripheral exudative haemorrhagic chorioretinopathy

Peripheral exudative haemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) is a lesion which is commonly confused with choroidal melanoma. They make up 8% of false positive choroidal melanoma referrals to a tertiary centre, and almost all cases of PEHCR are referred as suspect melanoma.36 Despite its appearance, PEHCR is actually a peripheral chorioretinal degeneration rather than a neoplastic lesion. It is almost universally a disease of Caucasian patients who are often asymptomatic.52 It appears as a dark brown lesion, typically 10mm wide by 3mm thick, in the peripheral fundus. Unlike choroidal melanoma, PEHCR shows a blockage on FFA and high reflectivity on ultrasound, and ophthalmoscopically stops at the ora serrata, whereas melanomas often continue into the pars plana. 89% of cases show spontaneous resolution so they are usually monitored.

Final thought

I hope this two-part series has clarified the different underlying causes and clinical implications of a wide range of pigmentary fundal lesions. The College of Optometrists is currently developing a new set of clinical management guidelines related to these lesions which should be released soon. Once they are, expect a third article in this series covering the main points taken from these new guidelines.

References

1 El Obeid AS, Kamal-Eldin A, Abdelhalim MAK, Haseeb AM. Pharmacological Properties of Melanin and its Function in Health. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 2017;120(6):515-522.

2 d’Ischia M, Wakamatsu K, Cicoira F, Di Mauro E, Garcia-Borron JC, Commo S, Galvan I, Ghanem G, Kenzo K, Meredith P and others. Melanins and melanogenesis: from pigment cells to human health and technological applications. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research 2015;28(5):520-544.

3 Brenner M, Hearing VJ. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2008;84(3):539-549.

4 Meredith P, Sarna T. The physical and chemical properties of eumelanin. Pigment Cell Research 2006;19(6):572-594.

5 Hu DN, Simon JD, Sarna T. Role of ocular melanin in ophthalmic physiology and pathology. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2008;84(3):639-644.

6 Wakamatsu K, Hu DN, McCormick SA, Ito S. Characterization of melanin in human iridal and choroidal melanocytes from eyes with various colored irides. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research 2008;21(1):97-105.

7 Friedman DS, Katz J, Bressler NM, Rahmani B, Tielsch JM. Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration - The Baltimore eye survey. Ophthalmology 1999;106(6):1049-1055.

8 Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-related macular degeneration: Etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Survey of Ophthalmology 2003;48(3):257-293.

9 Hu DN, Yu GP, McCormick SA, Schneider S, Finger PT. Population-based incidence of uveal melanoma in various races and ethnic groups. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2005;140(4):612-617.

10 Ly A, Nivison-Smith L, Hennessy M, Kalloniatis M. Pigmented Lesions of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Optometry and Vision Science 2015;92(8):844-857.

11 Denniston AKO, Murray PI. Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2014. xxxiv, 1069 pages p.

12 Lloyd WC, Eagle RC, Shields JA, Kwa DM, Arbizo VV. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal-pigment epithelium - electron-microscopic and morphometric observations. Ophthalmology 1990;97(8):1052-1060.

13 Kaur G, Anthony SA. Multimodal imaging of suspicious choroidal neoplasms in a primary eye-care clinic. Clin Exp Optom 2017.

14 Kim DY, Hwang JC, Moore AT, Bird AC, Tsang SH. Fundus autofluorescence and optical coherence tomography of congenital grouped albinotic spots. Retina-the Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases 2010;30(8):1217-1222.

15 Tiret A, Taiel Sartral M, Tiret E, Laroche L. Diagnostic value of fundus examination in familial adenomatous polyposis. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1997;81(9):755-758.

16 Traboulsi EI, Krush AJ, Gardner EJ, Booker SV, Offerhaus GJA, Yardley JH, Hamilton SR, Luk GD, Giardiello FM, Welsh SB and others. Prevalence and importance of pigmented ocular fundus lesions in gardners-syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 1987;316(11):661-667.

17 Shields JA, Eagle RC, Shields CL, Brown GC, Lally SE. Malignant Transformation of Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Ophthalmology 2009;116(11):2213-2216.

18 Shields JA, Shields CL, Slakter J, Wood W, Yannuzzi LA. Locally invasive tumors arising from hyperplasia of the retinal pigment epithelium. Retina-the Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases 2001;21(5):487-492.

19 Butler NJ, Furtado JM, Winthrop KL, Smith JR. Ocular toxoplasmosis II: clinical features, pathology and management. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2013;41(1):95-108.

20 Trevino R, Kiani S, Raveendranathan P. The Expanding Clinical Spectrum of Torpedo Maculopathy. Optometry and Vision Science 2014;91(4):S71-S78.

21 Golchet PR, Jampol LM, Mathura JR, Jr, Daily MJ. Torpedo maculopathy. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2010;94(3):302-306.

22 Qiu M, Shields CL. Choroidal Nevus in the United States Adult Population Racial Disparities and Associated Factors in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ophthalmology 2015;122(10):2071-2083.

23 Shields CL, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, Berman EL, Zahler JD, Hoberman DM, Dinh DH, Shields JA. Clinical spectrum of choroidal nevi based on age at presentation in 3422 consecutive eyes. Ophthalmology 2008;115(3):546-552.

24 Lewis DA, M AD. Choroidal Nevi. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 5 ed. London: Elsevier; 2013. p 2219 - 2230.

25 Cheung A, Scott IU, Murray TG, D SM. Distinguishing a Choroidal Nevus From a Choroidal Melanoma. EyeNet 2012 2/1/2012 1.

26 Chien JL, Sioufi K, Surakiatchanukul T, Shields JA, Shields CL. Chereidal nevus: a review of prevaence, features, genetics, risks, and outcomes. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2017;28(3):228-237.

27 Shields CL, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, Berman EL, Zahler JD, Hoberman DM, Dinh DH, Shields JA. Visual acuity in 3422 consecutive eyes with choroidal Nevus. Archives of Ophthalmology 2007;125(11):1501-1507.

28 Shields CL, Maktabi AM, Jahnle E, Mashayekhi A, Lally SE, Shields JA. Halo Nevus of the Choroid in 150 Patients The 2010 Henry van Dyke Lecture. Archives of Ophthalmology 2010;128(7):859-864.

29 Filloy A, Caminal JM, Arias L, Jordan S, Catala J. Swept source optical coherence tomography imaging of a series of choroidal tumours. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology-Journal Canadien D Ophtalmologie 2015;50(3):242-248.

30 Almeida A, Kaliki S, Shields CL. Autofluorescence of intraocular tumours. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2013;24(3):222-232.

31 Singh AD, Kalyani P, Topham A. Estimating the risk of malignant transformation of a choroidal nevus. Ophthalmology 2005;112(10):1784-1789.

32 Shields CL, Furuta M, Berman EL, Zahler JD, Hoberman DM, Dinh DH, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Choroidal Nevus Transformation Into Melanoma Analysis of 2514 Consecutive Cases. Archives of Ophthalmology 2009;127(8):981-987.

33 Shields CL, Cater J, Shields JA, Singh AD, Santos MCM, Carvalho C. Combination of clinical factors predictive of growth of small choroidal melanocytic tumors. Archives of Ophthalmology 2000;118(3):360-364.

34 Kivela T. The epidemiological challenge of the most frequent eye cancer: retinoblastoma, an issue of birth and death. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2009;93(9):1129-1131.

35 Thomas JV, Green WR, Maumenee AE. Small choroidal melanomas. A long-term follow-up study. Arch Ophthalmol 1979;97(5):861-4.

36 Shields CL, Manalac J, Das C, Ferguson K, Shields JA. Choroidal melanoma: clinical features, classification, and top 10 pseudomelanomas. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2014;25(3):177-185.

37 Fenton S, Sandinha T, Lee WR, Kemp EG. Massive extraocular extension as the presenting feature of a choroidal melanoma. Eye 2001;15:550-551.

38 Weis E, Shah CP, Lajous M, Shields JA, Shields CL. The association between host susceptibility factors and uveal melanoma - A meta-analysis. Archives of Ophthalmology 2006;124(1):54-60.

39 Singh AD, De Potter P, Fijal BA, Shields CL, Shields JA, Elston RC. Lifetime prevalence of uveal melanoma in white patients with oculo(dermal) melanocytosis. Ophthalmology 1998;105(1):195-198.

40 Shah CP, Weis E, Lajous M, Shields JA, Shields CL. Intermittent and chronic ultraviolet light exposure and uveal melanoma - A meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2005;112(9):1599-1607.

41 Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. CLINICAL SPECTRUM AND PROGNOSIS OF UVEAL MELANOMA BASED ON AGE AT PRESENTATION IN 8,033 CASES. Retina-the Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases 2012;32(7):1363-1372.

42 Singh AD, Damato BE, Jacob Pe, Murphy AL, Perry JD. Essentials of Ophthalmic Oncology. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Inc.; 2009.

43 The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Referral Guidelines for adult ocular tumours including choroidal naevi October 2009. London2009. p 4.

44 Kujala E, Damato B, Coupland SE, Desjardins L, Bechrakis NE, Grange JD, Kivela T. Staging of Ciliary Body and Choroidal Melanomas Based on Anatomic Extent. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2013;31(22):2825-+.

45 Shields JA, Shields CL. Management of posterior uveal melanoma: past, present, and future: the 2014 Charles L. Schepens lecture. Ophthalmology 2015;122(2):414-28.

46 Hawkins BS. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma: IV. Ten-year mortality findings and prognostic factors. COMS report number 24. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;138(6):936-51.

47 Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC. Melanocytoma (hyperpigmented magnocellular nevus) of the uveal tract - The 34th G. Victor Simpson Lecture. Retina-the Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases 2007;27(6):730-739.

48 Shields JA, Demirci H, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL. Melanocytoma of optic disc in 115 cases - The 2004 Samuel Johnson Memorial Lecture, Part 1. Ophthalmology 2004;111(9):1739-1746.

49 Thanos A, Gilbert AL, Gragoudas ES. Severe Vision Loss With Optic Disc Neovascularization After Hemiretinal Vascular Obstruction Associated With Optic Disc Melanocytoma. Jama Ophthalmology 2015;133(10).

50 Arepalli S, Kaliki S, Shields CL. Choroidal metastases: Origin, features, and therapy. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 2015;63(2):122-127.

51 Gass JDM, Gieser RG, Wilkinson CP, Beahm DE, Pautler SE. BILATERAL DIFFUSE UVEAL MELANOCYTIC PROLIFERATION IN PATIENTS WITH OCCULT CARCINOMA. Archives of Ophthalmology 1990;108(4):527-533.

52 Shields CL, Salazar PF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy Simulating Choroidal Melanoma in 173 Eyes. Ophthalmology 2009;116(3):529-535.

Ceri Probert is an optometrist practising in Wales, a tutor at Cardiff University Department of Optometry and is College of Optometrists council member, Wales.