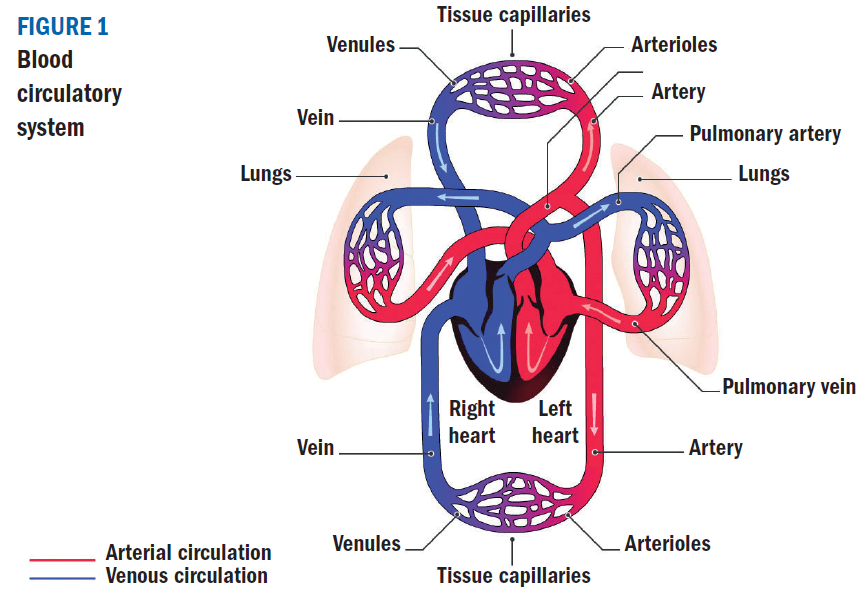

The cardiovascular system pumps blood from the heart to the organs of the body via a complex network of blood vessels called arteries, arterioles and capillaries. Blood is returned to the heart and lungs through a network of vessels called venules and veins. The cardiovascular system consists of the pulmonary circulation through the lungs, the coronary circulation supplying the heart muscle and the systemic circulation to the rest of the body (figure 1). The system pumps approximately five litres of blood around the body delivering life-giving oxygen and nutrients to the organs and removing carbon dioxide and waste materials.

Cardiovascular Disease

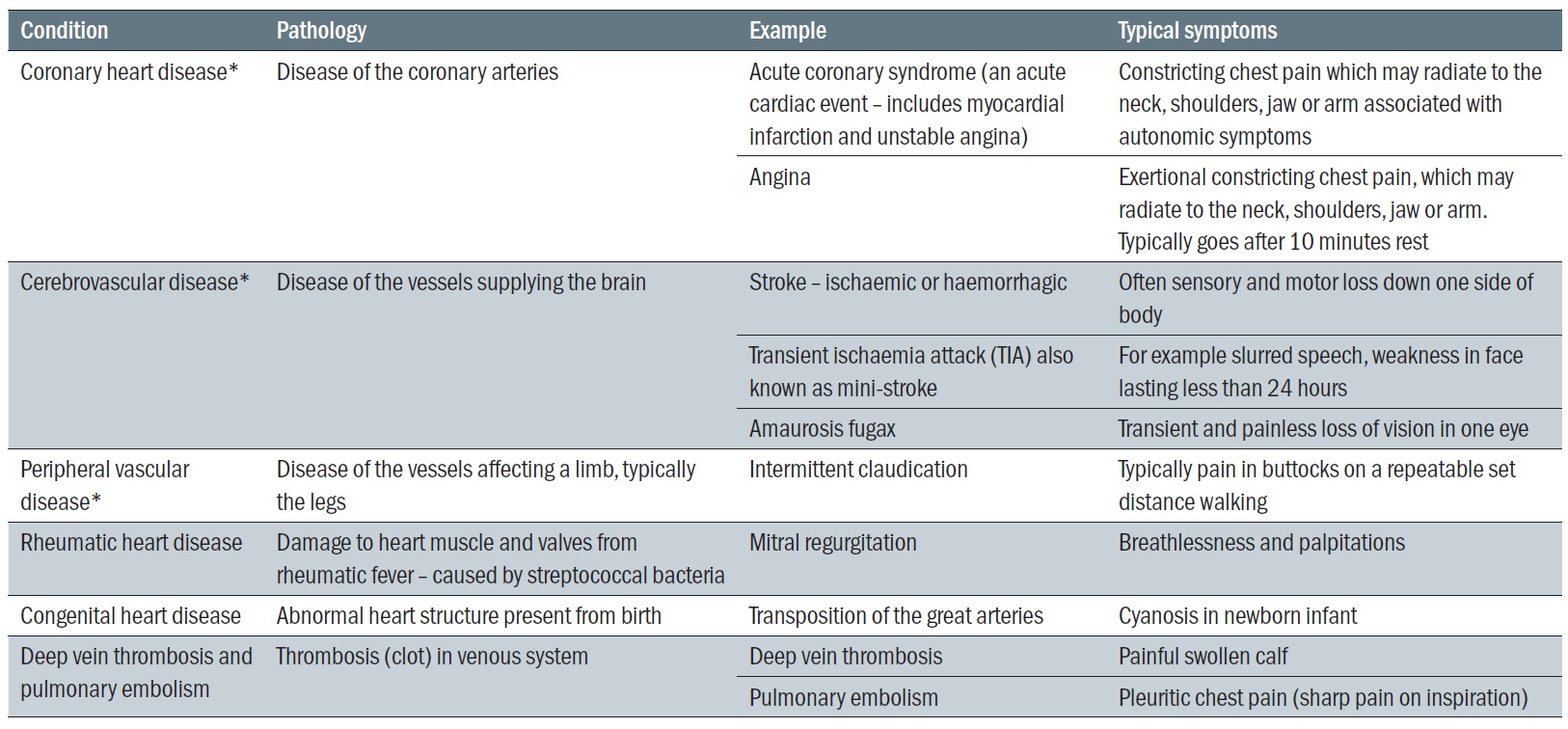

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a group of disorders affecting the cardiovascular system or to put even more simply the heart and blood vessels. These disorders disrupt function of the system itself or the organ(s) it is supplying. CVD includes conditions most people will have heard of such as coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease (see table 1). These conditions are caused by an atheroma or a thrombosis (a blood clot) blocking the blood supply to the heart, brain or limbs. An atheroma is a fatty deposit in the vessel wall that forms gradually over time. It is also called atherosclerosis or in layman’s terms ‘hardening of the vessel’ or a ‘plaque’. A thrombosis can form if the atheroma splits causing blood to clot and block the vessel causing a cardiovascular event such as a heart attack (myocardial infarction) or stroke (cerebrovascular accident). Emboli are ‘balls’ or fragments of atheroma that break away and cause a blockage at a more distal artery.

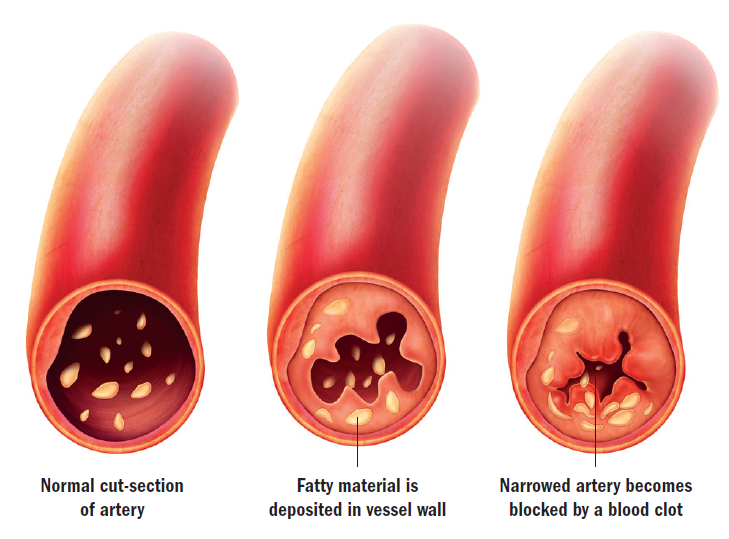

Table 1: Breakdown of cardiovascular diseases. * indicates further description in article

Table 1: Breakdown of cardiovascular diseases. * indicates further description in article

It is worth noting that not all CVD is caused by atheroma such as congenital heart disease or rheumatic heart disease. This article will focus on disorders caused by atheroma because they are common and are a significant public health burden. It will look at the symptoms, investigations and management of these conditions including medication as well as follow up in primary care. It will also look at hypertension in pregnancy in more detail because of the life-threatening nature of pre-eclampsia.

Nearly three million people in the UK are living with cardiovascular disease. Possible burdens to the individual include suffering, disability, financial losses and reduced quality of life. There is an economic cost to society from loss of workforce and funding NHS treatment. Worldwide, CVD is the leading cause of death. The UK has a higher incidence of death from CVD compared to many other developed countries. Most of these deaths are preventable by modification of risk factors. This makes CVD an important public health issue for the NHS supported by healthcare professionals such as eye care practitioners, pharmacists and mental health charities who may be the first to encounter early or undiagnosed disease and who can help signpost patients to NHS services.

Figure 2: Formation of atheroma and a blood clot (thrombus)

Prevention of cardiovascular disease

Preventing CVD falls into two categories; primary prevention which aims to prevent disease before an acute event and secondary prevention which focuses on reducing the impact of disease after an acute event.

- Primary prevention – aims to prevent disease before an acute event and secondary prevention which focuses on reducing the impact of disease after an acute event. Essentially, primary prevention is identifying and, where possible, modifying risk factors for CVD. Risk factors include those that are modifiable; hypertension, lipid disorders (including high cholesterol), smoking, diabetes mellitus, raised body mass index (BMI), diet, inactivity, kidney disease, alcohol consumption and those that are non-modifiable; age, family history, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. For example, a 45-year-old inactive male with a BMI of 35 would be encouraged to diet and exercise. A 55-year-old smoker with hypertension may be referred to a smoking cessation service.

- Secondary prevention – management depends on the underlying acute event and underlying disease process. Drug treatment and medical intervention will depend on evidence-based research for a given condition. For example, a 75-year-old with a stroke would be offered aspirin to help prevent the clumping of platelets around an atheroma or advice to a heavy drinker after a heart attack would include cutting down on alcohol consumption.

So how is primary prevention undertaken in general practice? NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence) recommends the QRISK2 risk assessment tool to help assess risk in primary prevention (www.qrisk.org/2017). Patients with a risk of over 10% of a cardiovascular event over 10 years are prioritised for a formal in-practice review of their health and risk factors and a statin will be offered. Patients over 40 should have their cardiovascular risk measured on an ongoing basis. Patients with diabetes, kidney disease, those with known cardiovascular disease or events are assessed and managed separately. Depression and anxiety is screened for in patients with a known chronic disease.

Needless to say, much time is taken in general practice to collect as much information as possible that is relevant to an individual’s health. This is done systematically, when a patient first registers with a surgery and by written invitation for a review every five years from the age of 40. Patients will also be assessed opportunistically when consulting for another reason. Depending on the practice, assessments may be done by a GP, practice nurse or pharmacist. Despite all these efforts, some patients do not take the opportunity for review. Encouraging patients to attend their GP for such checks will help us ensure we are detecting as much early disease as possible.

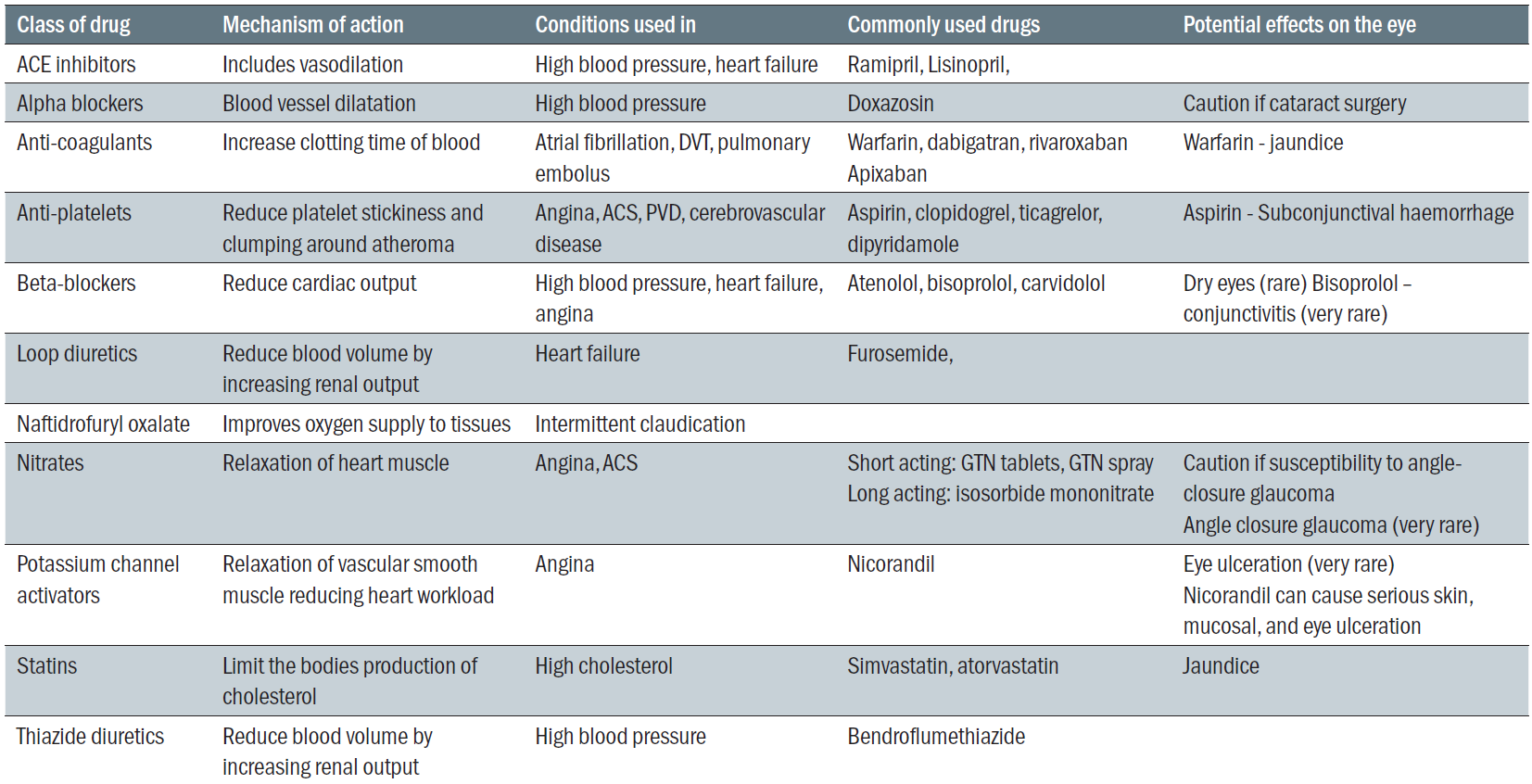

Specific secondary prevention strategies are discussed with the named conditions below. Table 2 gives a summary of major drug classes used in CVD management with an indication of where there may be ocular consequences.

Table 2: Classes of drug used in cardiovascular disease

Table 2: Classes of drug used in cardiovascular disease

Diabetes

Diabetes has been considered elsewhere (see Optician 31.07.15). It must be mentioned here, however, as is a significant risk factor for CVD. Tight diabetic glycaemic control is important in the primary and secondary prevention of CVD. Interestingly, diabetes can change the nature of symptoms in cardiovascular disease, for example chest pain in a heart attack may be absent or minimal in a patient who has had type 2 diabetes for many years. Blood pressure targets are often stricter in diabetes (also in renal disease) as poor control is associated with poor outcome. Patients with all types of CVD are screened for diabetes. Diabetic patients are seen at least once a year following blood testing in primary care. The practice diabetic specialist nurses normally see patients with support from a GP with an interest in the practice. The regularity of these appointments depends on how well the condition is managed and what complications are present if any.

Coronary heart disease

Angina

Cause and symptoms – angina is caused by temporary lack of blood supply to the heart muscle usually caused by atheroma. It usually occurs when there is additional demand on the heart during activity or emotional stress. Symptoms are of constricting central chest pain, which may radiate to the neck, shoulders, jaw or arm. Typically these symptoms will go within 10 minutes of resting.

Diagnosis – diagnosis can be made on clinical symptoms. Sometimes further investigations will be done. All patients will have an ECG to record the electrical activity of the heart. Blood tests are done to look for anaemia, kidney problems, diabetes, lipid disorders and thyroid problems. Other tests might be done if the diagnosis is unclear or if symptoms are severe. They look at function of the heart under strain or detect structural changes in the cardiac muscles. These include: myocardial perfusion scanning where radioactive dye is injected into a vein and its uptake into heart muscle is recorded; a stress echocardiogram, where the heart is ultrasounded after an injection is given to make it work harder; a cardiac MRI scan of the heart under stress; an angiogram where dye is injected directly into the coronary arteries to look for narrowing of the vessels; an exercise tolerance test where an ECG is recorded during exercise on a treadmill.

Management – treatment. Acute symptoms can be controlled with GTN tablets or a spray, which dilate the coronary arteries increasing blood supply to the heart. Other drugs help prevent symptoms, these include calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, long acting nitrates and potassium channel activators. If medical treatment is insufficient to control symptoms some patients may be offered coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or angioplasty where narrowed vessels are dilated and stented.

Management – secondary prevention. Attention will be given to encourage smoking cessation, weight loss if overweight to a normal BMI, physical activity, adoption of a Mediterranean diet, treatment of high blood pressure and not exceeding the recommended amount of alcohol. In some cases supervised exercise classes may be offered. Statins (usually atorvastatin) are offered to all patients with established cardiovascular disease. Regular bloods will be needed for the first few months after treatment.

Follow-up – once stable all patients will be seen at least annually by their GP. Prior to this appointment bloods and an ECG will be taken. Follow up will be individually tailored to a patient depending on their needs. For example, weight loss support will be given by a practice nurse or regular appointments with a GP/practice pharmacist if blood pressure readings are too high. Patients will be invited for a review by letter on an annual basis.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

ACS comprises:

- Unstable angina, which is caused by lack of blood supply to the heart at rest. Unlike angina changes will be seen on the patients ECG.

- NSTEMI (non-ST elevation myocardial infarction) is caused by platelet formation in the coronary arteries, symptoms are at rest and there are raised cardiac enzymes in the blood. Characteristic changes will be seen on the patients ECG.

- STEMI (ST elevation myocardial infarction) is caused by a clot in the coronary arteries with characteristic ‘ST’ changes in the ECG at rest.

Symptoms – constricting central chest pain, which may radiate to the neck, shoulders, jaw or arm. It occurs at rest and may be associated with autonomic symptoms (pale and sweaty). Pain typically lasts for more than 20 minutes.

Diagnosis – ECG and cardiac enzymes

Management – acute management. Details of these and the full range of cardiac investigations are outside the scope of this article. It is important to know that ACS is a medical emergency, an ambulance should be called. Cardiac arrest is possible, cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be necessary if a patient’s heart stopped. It may be helpful to know where your nearest defibrillator is and facilitate basic life support training in your practice. Although not endorsed by the NHS, mobile phone apps are now available that can tell you where your nearest defibrillator is. Patients may have drug treatment or primary angioplasty to immediately remove the blockage. The patient will be kept in hospital for at least five days some of which will be on a cardiac work or coronary care unit.

Management – secondary prevention. Unstable angina and NSTEMI patients are started on aspirin 75mg and clopidogrel. The latter is stopped after 12 months. Patients are started on atorvastatin as this has been found to improve outcome regardless of lipid levels. If patients have ongoing symptoms further interventions such as coronary angioplasty or a CABG may be necessary. Again, attention will be given to encourage smoking cessation, weight loss if overweight to a normal BMI, physical activity, adoption of a Mediterranean diet, treatment of high blood pressure and not exceeding the recommended amount of alcohol. Cardiac rehabilitation exercise classes may be prescribed. Return to work course are also available. Patients are not allowed to drive usually for up to four weeks depending on the details of the diagnosis and treatment. Further guidance is available at www.dvla.gov.uk and can be obtainable from a cardiac specialist nurse or the patient’s GP.

Some patients can have complications like heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias like atrial fibrillation. Pacemakers are sometimes required for slow heart rhythms. Further information on these conditions can be found at patient.co.uk.

Follow-up – again patients will be seen at least once a year by their GP following blood tests and an ECG. More regular appointments will be tailored to the patients needs depending on symptoms, whether blood pressure control is adequate and support needed to modify other risk factors. Patients will be invited for a review by letter on an annual basis. Advice regarding weight loss and diet is often given by the practice nurse. Complicated cases are followed up in secondary care. Patients may have access to a specialist cardiac nurse as well as seeing a cardiologist.

Patients with a STEMI are given aspirin and a second anti-platelet (for example clopidogel or ticagrelor), an ACE inhibitor, a beta-blocker and a statin tablet, otherwise secondary prevention is as for NSTEMI/unstable angina.

Cerebrovascular disease

Symptoms

- Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) – this is a focal cerebrovascular event that has no permanent neurological damage. Symptoms depend on which artery is affected. An embolus from the carotid artery could cause contralateral sensory and motor loss to the affected cerebral vessel.

- Stroke – leads to lasting neurological damage with symptoms lasting more than 24 hours. Commonly contralateral sensory and motor loss to the affected cerebral vessel occurs.

Diagnosis – TIAs are usually diagnosed by the patient’s story as symptoms have usually resolved before a doctor sees them. Strokes are confirmed by a CT head scan, which may show ischaemia or a bleed on the brain. Details of the treatments of strokes in hospital are not given here.

Management – secondary prevention. Patients with a TIA are often managed in an outpatient secondary care TIA clinic. Both stroke and TIA patients are given high dose aspirin for two weeks if there are no contraindication to treatment. Following a stroke first line treatment thereafter is with clopidogrel and for a TIA long term treatment is dipyridamole. If patients are in atrial fibrillation drugs to thin the blood to reduce the risk of embolic clots is considered. Carotid endarterectomy (removal of atheroma from the carotid artery) is considered in patients with a tight stenosis. Other risk factors are similar to coronary artery disease; encouraging smoking cessation, weight loss if overweight to a normal BMI, physical activity, adoption of a Mediterranean diet, treatment of high blood pressure and not exceeding the recommended amount of alcohol. Statins are recommended for all patients who have had TIAs and strokes.

Follow-up – again, patients will have a written invitation for a GP appointment annually but seen more often if intervention is needed to modify risk factors.

Peripheral vascular disease

Symptoms – in the lower limb symptoms start with pain typically in the buttocks after a set distance walking (intermittent claudication). This can progress to pain usually in the foot at night at rest, ulceration of the foot and finally gangrene of the foot.

Diagnosis – typical symptoms would be investigated by comparing the ratio of the blood pressure in the arms and legs (ankle brachial pressure index). A lower leg angiogram can show the presence of large vessel narrowing from atheroma. Ulcers can sometimes be managed in primary care with dressings done by the practice nurse. Definitive treatment is with bypass grafting, angioplasty and stenting. Amputation is sometimes needed. Supervised exercise is offered to those with intermittent claudication, naftidrofuryl oxalate is sometimes offered to patients with uncontrolled intermittent claudication.

Management – secondary prevention. Advice is similar to other CVD. Weight loss, exercise, managing hypertension, treatment with statins and smoking cessation. ACE inhibitors are sometimes used as they reduce cardiovascular mortality in patients with PVD. Aspirin, clopidogrel and aspirin plus dipyridamole reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.

Follow-up – patients will be seen once a year by their GP and further follow up will depend on symptoms and support to modify risk factors.

Blood pressure measurement and Hypertension

Hypertension is a major, yet preventable, cause of stroke and heart disease in the UK. In persons over 16 years, its prevalence is 31.5% in men and 29.0% in women. Diseases caused by hypertension cost the NHS £2billion per year. The majority of cases of hypertension are asymptomatic. Screening is therefore important to ensure that disease burden can be prevented.

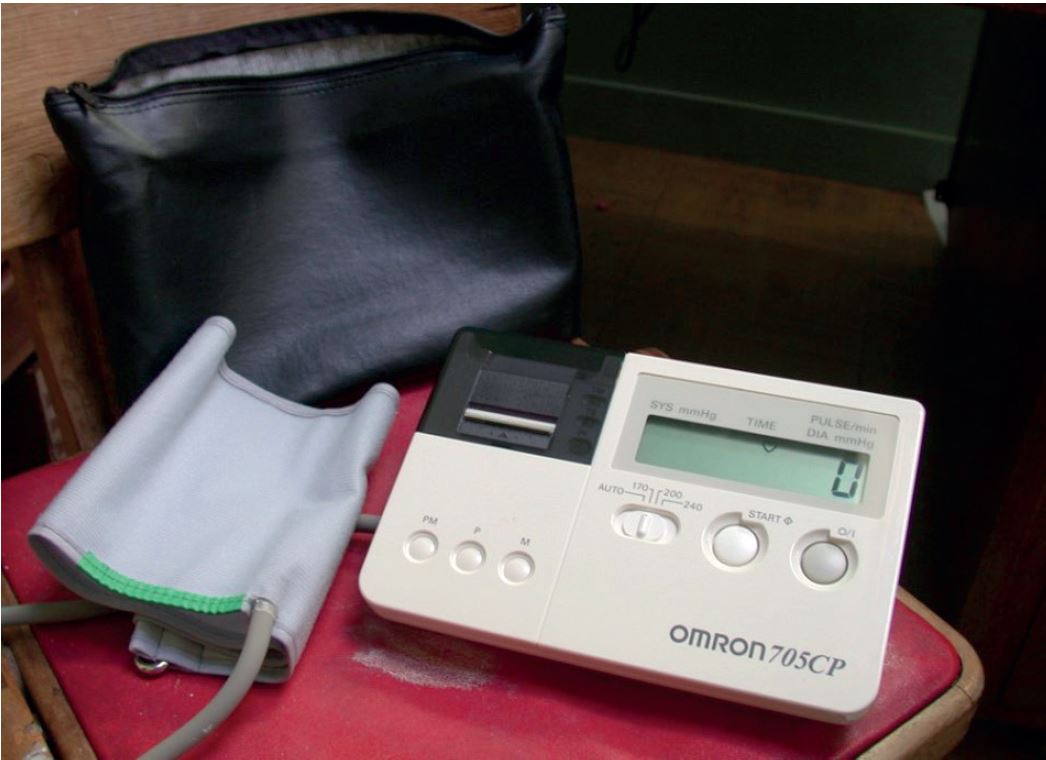

Blood pressure is measured with the cuff at the upper arm at the level of the heart with an automatic or manual sphygmomanometer (figure 3). In the case of a manual sphygmomanometer the stethoscope is placed over the brachial artery.

Figure 3: An automated sphygmomanometer

The systolic pressure is the maximum pressure in the brachial artery just after ventricular contraction and the diastolic pressure is the minimum pressure during left ventricular filling. It is recorded as systolic pressure/diastolic pressure in mm of mercury (mmHg). A normal systolic for an adult is <130/<85.

Hypertension can be chronic (chronic hypertension) or acute (malignant or accelerated hypertension). Chronic hypertension (BP 140/90 but lower in certain conditions) is usually asymptomatic. Hypertension is grade 1 (mild) 140-159/90-99, grade 2 (moderate) 160-179/100-109, grade 3 (severe) systolic >/= 180 diastolic >/=110, isolated systolic grade 1 149-159/<90, isolated systolic grade 2 >/= diastolic <90.

Malignant hypertension is a distinct form of hypertension (>180/110 with characteristic retinal changes). It is a medical emergency and must be referred the same day. Patients should be told to attend the emergency department without delay.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is when patients have their blood pressure taken over a period of 24 hours. This is offered to patients who have a blood pressure of over 140/90 as well as high-risk patients and patients with poor blood pressure control. Readings over 140/90 during the day and 125/75 during the night are abnormal. It is useful in white coat hypertension where patients have higher blood pressure readings when taken in a healthcare setting.

Home monitoring can also be helpful to increase the number of readings and to avoid white coat hypertension.

Weight loss if overweight, dietary modifications including reduced salt, reducing alcohol and stopping smoking can all reduce blood pressure. Often more than one drug is needed to treat a high blood pressure. Drugs that are used include, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics and alpha-blockers.

Special cases

In patients with orthostatic symptoms (dizziness on standing or previous collapse) blood pressure should be measured after one to three minutes standing with the arm supported.

Blood pressure in children varies with age, it is only occasionally taken in a primary care setting. Exercising before blood pressure is taken can give a false low reading.

Automatic machines can give unreliable or error readings in atrial fibrillation. Manual blood pressure readings should be taken if a patient is known to have atrial fibrillation or if their pulse is irregular.

A difference in blood pressure of more than 20mmHg is regarded as abnormal and should be assessed by a clinician. This should be immediate if there is any suggestion of dissection of the aorta.

Any practice offering blood pressure measurements should have protocols in place to ensure staff are adequately trained, equipment is regularly validated, maintained and calibrated and staff know what to do with an abnormally low and high readings.

Lipid disorders

A raised cholesterol (a low density lipoprotein), or a raised fasting triglyceride (a very low density lipoprotein) are both lipid disorders that are associated with increased cardiovascular risk. There are several primary lipid disorders, some of which are associated with changes in and around the eye. Primary lipid disorders carry a high risk of CVD. They are often managed in secondary care. Secondary dyslipidaemia can be caused by several medical conditions such as diabetes or thyroid disorders; certain drugs such as anti-psychotics or beta-blockers; or lifestyle choices like smoking, excessive drinking, lack of exercise and poor diet.

Obesity is also associated with lipid disorders. Both primary and secondary prevention of CVD involves treatment of lipid disorders usually with a statin such as atorvastatin as well as managing any underlying medical cause or responsible drug. Primary lipid disorders may require addition medication. Weight loss, change in diet, alcohol consumption, smoking cessation and exercise can also help to reduce abnormal lipids. Practice nurses are able to see patients to support them with these lifestyle changes.

Pregnancy – what to watch out for

Any suggestion of hypertension in a pregnant woman must be taken very seriously due to the risk it imposes on the mother and unborn child. Hypertension can be pre-existing or occur due to the pregnancy. It is defined as:

- Gestational hypertension – a blood pressure greater than 140/90mmHg after 20 weeks gestation.

- Pre-eclampsia – hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks gestation.

- Eclampsia – seizures in a patient with pre-eclampsia.

- Chronic hypertension – a blood pressure greater than 140/90mmHg prior to pregnancy or before 20 weeks gestation.

Any pregnant woman with signs of hypertensive retinopathy must have their blood pressure and urine checked by a midwife or doctor to ensure that hypertension is picked up and managed promptly.

The future – how should primary care and opticians share information?

A good understanding of cardiovascular disease is important for all in the primary care community. Not only should this help to ensure appropriate referral for diagnosis and treatment when possible, but importantly helps improve compliance.

Certain patient groups are at particular risk of not attending GP appointments. These include patients with mental health problems, learning disabilities and those with a low socioeconomic status. Encouraging non-attenders, especially in these groups who are more likely to have cardiovascular disease, could help save lives and reduce the burden of CVD.

Dr Catherine Williams is a qualified GP living in the Bristol area. She is a member of the Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of General Practice and has additional diplomas from the College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and a certificate in Mountain Medicine.