The NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme comes under the umbrella of Public Health England, which is the operational executive agency within the Department of Health that exists to protect and improve the nation’s health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. One of the ways it does this is the delivery of specialist public health services, including health screening.

National population screening programmes are implemented in the NHS on the advice of the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC), which advises ministers in the four UK countries and makes recommendations based on independent, evidence-based research and studies. Screening programmes are monitored to ensure they are safe and effective and meet national standards by the Screening Quality Assurance Service. Public Health England leads the NHS Screening Programmes and hosts the UK NSC secretariat.

Complications of Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, usually just referred to as diabetes, is a chronic metabolic disorder in which blood sugar levels are raised for prolonged periods of time. It is the result of the pancreas not producing enough (or any) insulin or as a result of insulin resistance when the cells of the body do not respond properly to insulin.

If not diagnosed and treated, or if it is poorly controlled, diabetes has major impacts upon health caused by prolonged damage to the vascular system affecting both the macrovascular and microvascular vessels. This can lead to chronic complications such as cardiovascular disease and heart attack, cerebrovascular disease and stroke (macrovascular), and chronic kidney disease, renal failure and dialysis, foot ulcers and ultimately amputation and damage to the eyes leading to serious sight threatening complications (microvascular).

Severe sight loss is one of the most worrying consequences for people living with diabetes. Until recently diabetes eye disease was the number one cause of blindness in the working age population (16 to 64 years).1 Since the launch of the national eye screening programme in 2003 this has been overtaken by inherited retinal disorders as the leading causes of certifiable blindness in this age group in England and Wales according to data published by Public Health England in 2014. This is probably due to a number of factors including better glycaemic control as a result of the introduction of the National Service Framework for Diabetes, new and effective treatments for the ocular complications of diabetes and probably most importantly, the introduction of a nationwide diabetic eye screening programme.

In 2003 the implementation of diabetic eye screening (DES) in England was announced as part of the Delivery Strategy for the National Service Framework for Diabetes and, by 2008 the whole of England was covered by locally commissioned diabetic eye screening programmes. It currently invites over 2.5 million people for screening every year, and this is increasing annually as the number of people identified with diabetes continues to increase every year. This article will look at the structure and pathways of the English Diabetic Eye Screening Programme

Why is Diabetes Eye Screening an effective Public Health Initiative?

The main reason for screening for diabetic eye disease is to reduce the incidence and prevalence of sight loss caused by diabetes through the early detection of the retinal changes associated with this condition, followed by the appropriate management to reduce the progression of the disease. The degree of intervention varies from better management of the diabetes through to major ocular interventions.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) produced evidence that improving glucose control in Type 1 diabetes had a significant impact on both the development and progression of diabetes eye disease. Similarly, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed an improvement in outcomes with better control in Type 2 diabetes. This last study also revealed the impact of good blood pressure control on the rate of progression of retinopathy.

One of the main criteria for establishing a disease screening service is that the disease should be treatable, with better outcomes if it can be detected at an early stage. As these studies show, improved management of diabetes and blood pressure are the first line of attack for managing diabetes eye disease and can have a significant impact on the progression of the disease.

With the advent of digital retinal cameras, it is also now possible to document and record the retinal lesions and how they progress over time. Diabetes eye disease meets all the criteria required for population screening of a disease.

Figure 1: Disc centred image

Figure 1: Disc centred image

The ‘Common Pathway’ for Diabetic Eye Screening Care

Many of the local eye screening programmes that were commissioned after the launch of the national eye screening programme in 2003 grew out of small local initiatives that had developed their own approaches to diabetes eye screening over many years and indeed, it was the experience and expertise of these initiatives that provided the evidence for the importance of establishing a national programme. Consequently, there was often little consistency between the approaches of these local programmes with variations in grading and referral processes as well as differences in what were considered to be screening, diagnostic and treatment services. In the interests of establishing national enforceable standards and ensuring that data collected was equivalent and comparable, a ‘common pathway’ was introduced between April 2013 and March 2014.

Important elements of the common pathway for diabetic eye screening pathway include:

- Provision of primary, secondary and arbitration grading.

- Only retaining annual recall patients in the screening service.

- Management of patients who:

o Require more frequent monitoring (such as three or six monthly) or screening in pregnancy by recall to surveillance clinics outside the routine screening pathway.

o Have unassessable images by recall to slit lamp biomicroscopy surveillance clinics. - Reviewing all images with referable disease by the clinical lead or designated senior grader to decide a referral outcome grade that provides the referral outcome.

One of the significant changes adopted by the common pathway was the recognition that in certain cases of ‘borderline’ sight- threatening retinopathy it makes sense to allow for more frequent monitoring without referral to the hospital eye services. Many local programmes had previously negotiated similar arrangements with their ophthalmology providers. The common pathway formally acknowledged this and created a parallel track called the digital surveillance pathway that enables a certain cohort of mainly early maculopathy patients to be kept under surveillance within the screening programme without the need for a referral. The programme is required to have a consultant ophthalmologist with medical retina experience to have an overview of the surveillance pathway according to local protocols and based on best evidence. I will discuss this pathway later in this article.

The common pathway also clarifies the specific circumstances in which patients can be suspended or excluded from screening. Obviously patients who are currently under the care of ophthalmology for diabetic retinopathy should be suspended and not be invited for annual screening until discharged back to the eye screening programme either for treatment completed or for failure to attend their appointments. Failsafe procedures have also been clarified such that patients are also recalled if there has been no ophthalmology feedback beyond one year from the last update to catch patients who may have fallen between the cracks of the interface of screening and ophthalmology.

The introduction of features-based grading at the same time as the common pathway emphasised the relationship between features and screening outcomes.

The changes to the grading criteria include:

- Defining the R2 pre-proliferative level.

- Defining groups of exudates for maculopathy.

- Introduction of a stable treated proliferative retinopathy grade (R3S).

- Simplification of image quality into adequate and inadequate.

I will discuss these features in more detail in the following two articles of this series.

Figure 2: Macula centred image

Figure 2: Macula centred image

The patient pathway for annual retinal screening

The key stages of the patient journey for the common pathway for annual eye screening are:

- Identifying the cohort to be invited for screening: Anyone with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus aged 12 and over should be seen for annual diabetic retinopathy screening in the NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme (NDESP) except for people who have no perception of light (NPL) in both eyes. (Other exclusions also apply.) Each Diabetes Eye Screening Programme is required to hold a collated list of people with diabetes registered with a GP practice in the area covered by the programme which they must update regularly as people move into and out of area, and are newly diagnosed or are deceased.

- Invite to an eye screening appointment: Everyone on the collated list is invited annually for screening. This can either be to a fixed appointment or an invitation to arrange an appointment at a time and place of their convenience. This will vary depending on the type of screening service being offered. In inner city areas with dense populations and good transport links, fixed centrally located clinics are an effective model whereas in large rural areas with a scattered population and less frequent transport links a multi-site and/or mobile screening service can offer better access and availability of appointments.

- Failure to attend: If people fail to attend the first invitation they are re-invited at least once. Evidence from the London North East DESP shows offering multiple appointment opportunities increase the uptake of screening. If someone with diabetes still does not attend, their GP is notified and they are then invited again at their next annual due date.

- Screening event: When the patient attends their screening event the following procedures are carried out:

o Pre-Screening & Visual Acuities: When the patient arrives for their appointment it is important to confirm the demographic details (among many things to avoid screening the wrong patient and to avoid sending a report to the wrong address) and obtain consent for the screening procedure. They are initially pre-screened and visual acuities are recorded. Some programmes also record a brief history and symptoms including any history of attendance in the Hospital Eye Service. The patient is then dilated with mydriatic eye drops.

o Digital Imaging: After a suitable period of time to allow for dilation (20 minutes or more) digital images are taken. In general, each eye will have a macula centred and a disc centred image taken (figures 1 and 2). Anterior eye images are also useful if there are media changes to help identify possible causes of reduced visual acuity (because this is a factor in determining the maculopathy grade). The recent changes to the grading criteria allow for a ‘jigsaw’ approach so if the digital images are poor, taking a series of images that cover the area of retina normally seen in the macula/disc centred model is considered acceptable. The images are then stored on a server (with suitable back-up in place) for grading at a later stage. In some cases, the image quality will not be acceptable or it may not be possible to photograph the fundus (poor mobility or reduced cognitive ability are often a cause of this) and I will cover that later in the article. Some programmes also encourage photographers to review the images taken and to photograph additional images if a lesion is discovered at the edge of the image to enable better identification of the lesion. - Grading pathway: Once the digital images have been taken and the encounter closed, the patient enters the grading pathway before a final grade and management outcome is decided. The final outcomes possible include:

o Annual recall to eye screening.

o Recall to a slit lamp biomicroscopy surveillance clinic.

o Recall to a digital surveillance clinic in three or six months – note pregnant patients are seen at frequent intervals with digital surveillance.

o Referral for sight-threatening diabetes eye disease.

o Urgent referral for proliferative diabetes eye disease.

o Referral for non-diabetes sight-threatening eye disease – according to local protocols, which may include referral via the GP. These patients are not excluded from the screening pathway and are recalled annually.

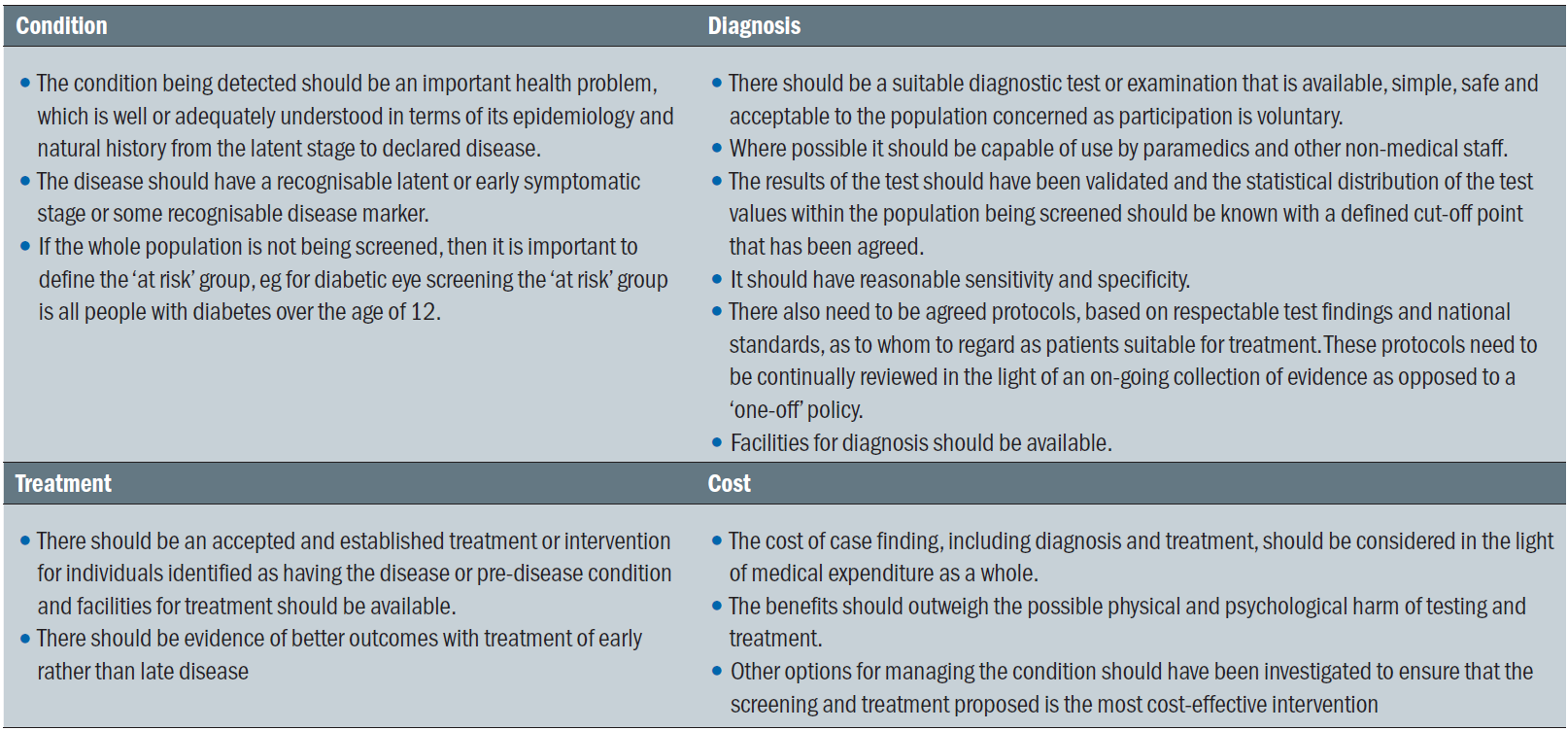

Table 1: Principles of screening for disease

Table 1: Principles of screening for disease

Single common grading pathway

All images are initially reviewed and graded by a primary grader using the ‘features-based’ grading scheme mentioned above. The grader identifies specific retinal features and ticks the relevant boxes in the grading template which generates a nationally recognised diabetic retinopathy grade (R0, R1, R2, R3S, R3A) and maculopathy grade (M0, M1).

The pathway then followed by the patient is determined by the initial primary grade as discussed below:

o R0M0: In 90% of the outcomes where the primary grader detects none of the features of diabetic retinopathy the results are sent to the patient and GP and the patient will be re-invited for routine annual screening. As part of the internal quality assurance of the programme the other 10% will go forward in the grading pathway to have a secondary grade. Primary graders outcomes against final grade are monitored regularly to highlight any areas where additional training is required to maintain excellence within the grading pathway. New graders also initially have 100% of their primary grades reviewed at secondary until it can be shown that their grading quality is consistent and of a high standard.

o R1, R2, M1 and non DR lesions: All cases of diabetic eye disease (excluding proliferative eye disease) detected at the primary grade will go forward in the grading pathway to a secondary grade. The secondary grader is not able to see the primary grade.

o R1M0: If the primary and secondary graders agree on this final grade the results are sent to the patient and GP and the patient will be re-invited for routine annual screening.

o Referable retinopathy: R1M1, R2M0, R2M1: If the primary and secondary graders agree on this grade the patient goes forward in the grading queue to the Referral Outcome Grader for a final assessment.

o R3S, R3A: If proliferative eye disease is detected at primary grade or subsequently at secondary grade the patient is fast-tracked directly to the Referral Outcome Grader

o Unassessable: If the primary or secondary grader considers that the images are not of sufficient quality to be safely graded they go forward to the Referral Outcome Grader.

o Urgent non-DR lesion: If the primary or secondary grader considers that there is a potentially sight-threatening non-diabetes related lesion they go forward to the Referral Outcome Grader

- Arbitration Grade: If the primary and secondary graders disagree on the grade it will go forward to the arbitration grader. The arbitration grader does have access to both the primary and secondary graders outcomes and is the final arbiter for the grade. The arbitration grader is in a good position to build an impression of individual graders performance.

- Referral Outcome Grade: This is considered to be the final outcome grade and this is carried out by a senior level grader supervised by the clinical lead. This grader is able to choose the final action outcome which includes referring patients to the Hospital Eye Services (including urgently for proliferative diabetes eye disease), slit lamp biomicroscopy (for unassessable images), digital surveillance (for borderline routine referable grades) or routine annual screening (for non-referable grades).

The referral pathway for digital surveillance

Diabetes Eye Screening is an annual process. If the patient needs more frequent monitoring they are seen in a parallel pathway within the programme called Digital Surveillance.

One of the outcomes at the Referral Outcome Grade is recall to the digital surveillance pathway for patients with early maculopathy (with good/stable visual acuities and minimal exudation) who need more frequent review, usually six months but are not yet requiring referral in agreement with local protocols for the ophthalmology providers.

Patients seen within this pathway also include pregnant women who are known to be already diabetic who are recalled approximately every three months (see paragraph later).

Outcomes from the digital surveillance pathway include:

- Patients unsuitable for digital imaging, slit lamp biomicroscopy or treatment are excluded from screening in line with the local policy for exclusions.

- Patient is returned to the annual routine screening pathway.

- Patient is referred to the slit lamp biomicroscopy pathway.

- Patient is referred to the Hospital Eye Services for treatment of sight threatening diabetic retinopathy or non-diabetes related eye disease.

- Patient is recalled to digital surveillance at the appropriate interval.

Referral pathway for slit lamp biomicroscopy surveillance

Patients with ungradable images in one or both eyes are seen for a final outcome grade by the referral outcome grader. They are recalled to the slit lamp biomicroscopy pathway. The outcomes in this pathway include:

- If they fail to attend after two invitations, the GP is notified and they are recalled to the annual eye screening pathway.

- Patient is referred to the Hospital Eye Services for treatment of sight threatening diabetic retinopathy or non-diabetes related eye disease via appropriate referral pathways.

- Patients unsuitable for digital imaging, slit lamp biomicroscopy or treatment are excluded from screening in line with the local policy for exclusions.

- Patient is recalled to the slit lamp biomicroscopy pathway, either annually or at a six-month interval, if one or both eyes will require slit lamp examination in the future.

- If one eye is screenable by digital imaging but the second is unscreenable by any method.

o They are recalled to routine annual screening if the pathology is untreatable and known – eg long-standing corneal scarring with no treatment indicated.

o They are referred to treat the pathology of the unscreenable eye, eg for cataract surgery and recalled back to annual screening once they are discharged from the hospital eye services.

Referral pathway for management of sight threatening diabetic retinopathy

Patients may be referred into the hospital eye services from the Referral Outcome Grade of the screening pathway, from the digital surveillance pathway or from the slit lamp biomicroscopy pathway.

Once the referral is received the patient enters the call-recall system of the ophthalmology provider and an appointment is made within the treatment guidelines (discussed in the next couple of articles on grading). The patient is seen and assessed and a management plan is initiated with recall as required. The patient remains in the care of the hospital eye services until such time as their treatment is completed and they are discharged back to the screening service or if they fail to attend they are discharged back for a further assessment in eye screening.

Responsibility for the patient passes from NHS England who commissions the screening programme to the CCG that commissions the local hospital eye services providers.

Pathway for pregnant patients

If a patient is flagged up to the diabetes eye screening programme as being pregnant or presents for routine screening and informs the programme that she is pregnant, she is monitored within the digital surveillance pathway at more frequent screening intervals, unless she is already in the care of the hospital eye services for sight threatening diabetic retinopathy, in which case the HES is notified of the pregnancy.

If the result of the first digital screening shows:

- Sight threatening retinopathy (R2, R3A, R3S, M1 or Ungradable) the patient is referred to ophthalmology and monitored there for at least six months post-natal.

- Background retinopathy (R1M0) the patient is recalled at 16 to 20 weeks of pregnancy and then at 28 weeks of pregnancy

- No diabetic retinopathy the patient is recalled at 28 weeks of pregnancy.

- If the grade at 28 weeks of pregnancy is R0M0 or R1M0 the pregnancy flag is removed and the patient is recalled for routine annual screening in the normal pathway.

- If the grade at 28 weeks shows sight threatening retinopathy (R2, R3A, R3S, M1 or Ungradable) the patient is referred to ophthalmology and monitored there for at least six months post natal.

Pathway Standards

In April 2017 the NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme introduced revised Pathway Standards of which there are now 13.

The changes were made to ensure that commissioners, providers, programme users and the quality assurance service have access to:

- Reliable and timely information about the quality of the screening programme.

- Data at local, regional and national level.

- Quality measures across the screening pathway without gaps or duplications.

- A consistent approach across all screening programmes.

- A burden of data collection that is proportionate to the benefits gained.

The goal is to provide a structure that embeds continuous improvement by allowing providers and commissioners to identify those areas within the local programme where improvements can most effectively be made across the pathway.

The previous standards did include the structural requirements which make up each programme such as workforce and IT, but these are now driven by service specifications and monitored through commissioning and other quality assurance methods.

Outcome standards are also no longer included because these are best measured at a population level and eye screening is only one of many contributors to the outcome. A review is currently under way by the operations team of the national screening programme to determine the best approach to outcome monitoring.

The Role of Optometry within Diabetes Eye Screening

There are various opportunities for optometrists within the National Eye Screening Programme. Some programmes, such as London North East employ optometrists as image graders, slit lamp providers and clinical managers. In other areas diabetes eye screening is located within optometrist practices either as a stand-alone scheme or as one strand within a more multi-element programme. The level of involvement will vary depending on the way the scheme has developed over time, and also how it has been commissioned.

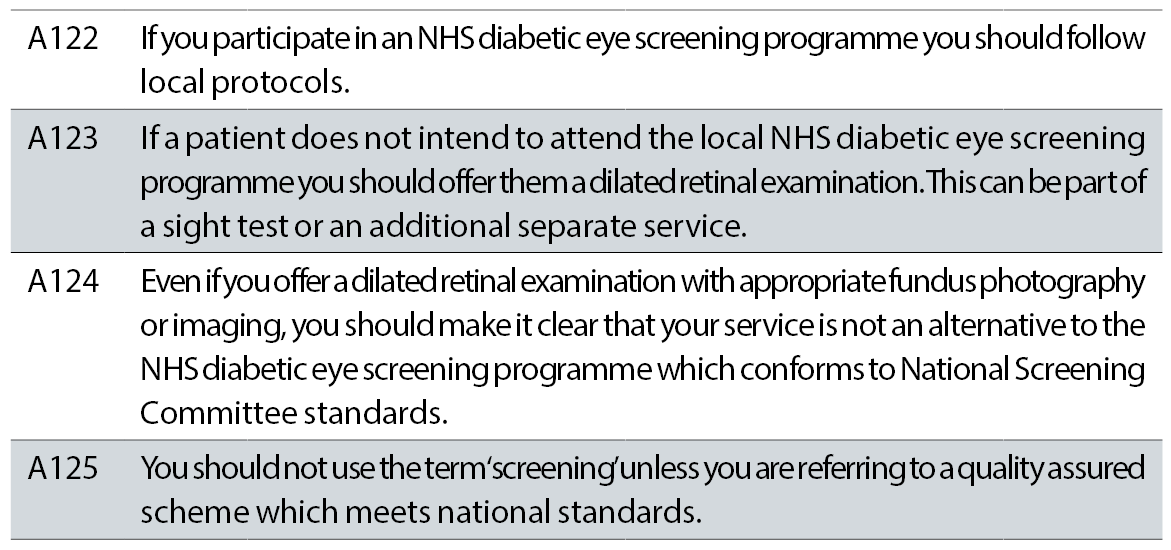

The College of Optometrists has issued guidance for Optometrists – see table 2.

Table 2: College of Optometrists guidance for Optometrists

Table 2: College of Optometrists guidance for Optometrists

Conclusion

The NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme is a quality assured national screening programme that is proving to be a key element in the reduction of the impact of sight threatening eye disease as a result of diabetes. As the pathways have evolved it is allowing for an appropriate flexibility for the management of specific cohorts of patients which is more convenient for the patients and more cost-effective for the NHS.

There are still issues to be addressed. These include:

- How to reach the persistent non-attendees who are likely to be patients with poor compliance of their diabetes management and hence at a much greater risk of sight loss.

- How to incorporate new and improving technologies such as OCT within the eye screening pathway to provide more appropriate referrals and better use of limited resources.

It is a continually evolving service where improvements are being driven by ongoing quality assurance and a very tight relationship between the commissioners and the providers.

Peter Mitchell is senior optometrist grader London North East DESP.

References

- Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16-64 years), 1999-2000 with 2009-2010. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004015. (doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013- 004015).