Once the patient encounter has closed and the digital images have been saved using the screening software, the images enter the grading pathway and go through a series of grading stages to produce a final outcome grade. This final grade will determine the subsequent patient pathway including the management of any diabetes eye disease detected during the screening process. The pathways within the NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme were discussed in more detail in the first article of this three-part series (Optician 27.10.17).

The following two parts of this series will examine the grading process in more detail and discuss the various lesions associated with diabetes eye disease and how they indicate the degree of progression. It will examine the management protocols associated with the various levels of disease severity.

The Grading scheme

In 1968 the World Health Organisation published guidelines on the ‘principles of screening for disease’ as developed by Wilson and Jungner.1

Two of the principles that need to be met are:

- The condition being detected should be an important health problem, which is well or adequately understood in terms of its epidemiology and natural history from the latent stage to declared disease.

- The disease should have a recognisable latent or early symptomatic stage or some recognisable disease marker.

Diabetes eye disease is a progressive condition that goes through a number of changes from its very earliest manifestation to its sight threatening stages. These changes occur as a continuum but it is possible to study the development of the retinal lesions as the disease process unfolds and start to divide the retinal appearances into a number of different stages, each of which is associated with a risk of progression to sight loss. Its natural history is well understood, it can be detected at a very early stage and there are degrees of intervention available depending upon the stage of retinopathy detected in screening.

The single common grading pathway now adopted throughout the NHS diabetic eye screening programme is only one of many different retinal grading schemes. The number of stages in any specific grading protocol depends upon the purpose of the scheme and to some degree this is influenced by the resources available to manage the outcomes. Examples include very detailed international systems used in research studies like the ETDRS (Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study) to simpler and more practical schemes as used in population screening programmes. Within the four nations of the UK, different national programmes use different schemes and the Scottish programme breaks up the progression stages into more levels than the English programme. The division into different stages is to some extent an arbitrary one and there will always be cases that sit on the boundary and it can be challenging to decide on which side of the boundary to grade the images, particularly as this will impact upon the final management. Some cases will obviously sit in the middle of a grade level but some cases are open to interpretation and it is healthy that differences of opinion exist in cases that are borderline. This is one of the reasons that images go through a staged grading approach including an arbitration grade by an experienced senior grader for any cases of disagreement.

How the scheme is divided up into grade levels relates to the risk of sight loss associated with the various lesions and also reflects the treatment resources available to manage the diabetes eye disease. The point at which patients are referred for treatment varies in different countries depending upon the availability of ophthalmologists and access to treatment options such as laser. As evidence and data from diabetes eye screening programmes increases (some programmes in the UK have now been running for well over 10 years and have significant data on disease progression in a normal population as opposed to the carefully chosen populations used within a research sample study like ETDRS) the grading schemes can be refined and there were changes introduced to the NHS grading scheme during the launch of the common pathway in 2013/14. These changes adjusted the retinal lesions and qualified some of the definitions associated with each level of retinopathy in the English national programme to give greater discrimination between observable and referable lesions.2

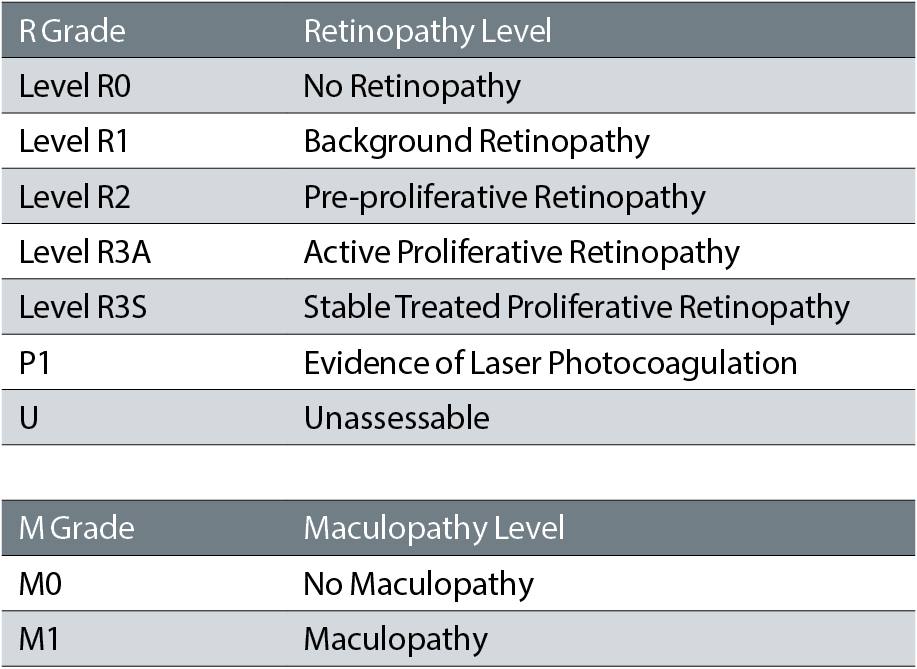

This article will discuss the current Grading Scheme being used in the English programme. The grading levels used are summarised in table 1.

Table 1: Grading Levels

Grading an image

Grading is essentially an image recognition task and knowing the lesions, how they appear and how they vary with disease progression is essential to be able to interpret an image. It is important to approach grading an image systematically, particularly if you are grading a series of images over a period of time to avoid visual fatigue and ‘zoning out’. It is not enough to just look at an image and assume you will see every lesion. A systematic study of the image so that all parts are examined – eg starting with the disc and following the major vessels, helps to ensure that no lesions are missed.

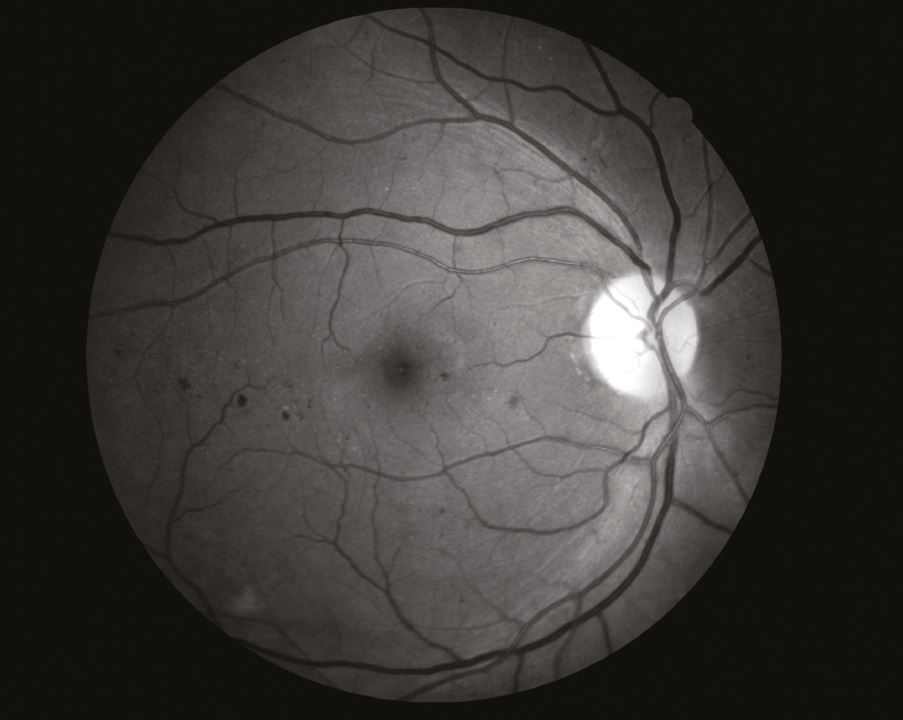

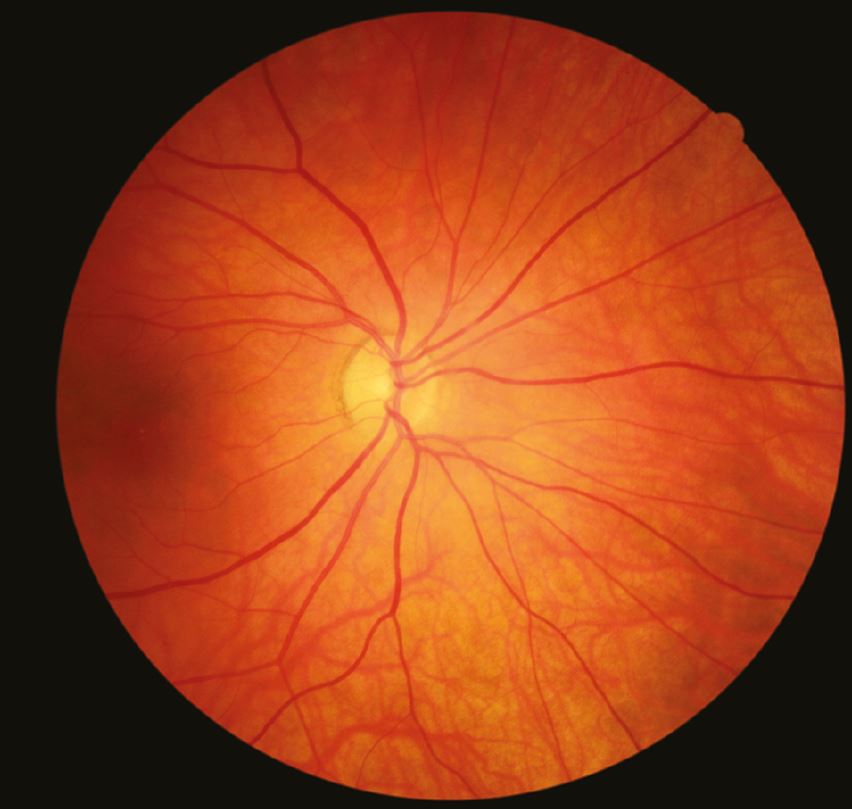

Sometimes it can be hard to detect the retinal lesions, especially if the image quality is less than perfect so the grading software includes various image manipulation tools that help to highlight lesions. For example, ‘Red Free’ can pinpoint a small microaneurysm much more quickly than trying to locate a small red spot against a red/orange background (figure 1). There are also contrast enhancement, zoom and magnification tools available. It is also possible to view images from different grading encounters side by side to detect any changes over time, however small they may be.

Figure 1: Red free image

It can be easy to interpret a camera artefact as a retinal lesion if the grader is not exercising more than a superficial level of engagement with the images (figure 2).

Figure 2: Artefact (marked by the arrow)

Most cameras appear to have various spots that are visible on the final images. These will always appear in the same place relative to the image boundary whereas retinal lesions will move relative to the image boundary but not relative to the retinal features (figure 3).

Figure 3: Artefact maintains position despite retinal image movement

Flipping between the images from a single encounter shows up the artefacts easily and they can then be discounted as retinal lesions. Screen artefacts (marks on the Visual Display Unit) can also be a source of confusion. By magnifying the image, they can be seen remaining in the same place on the screen and hence be discounted as retinal lesions.

The level of retinopathy is determined within the software using a ‘Features-Based’ approach. The grader identifies the various lesions present and selecting this feature produces a grade as determined by rules applied within the software. It is important that lesions are only recorded if they are definitely present so for example, using both colour and red-free images helps to distinguish between a pigment spot versus a blot haemorrhage. Beware of over-magnifying an image as the pixilation can appear to show retinal features that are not actually present, especially at the edge of an image.

Image Quality

Image quality will vary across the range of patients seen for eye screening. It is affected by a range of factors including media opacities, pupil dilation and patient mobility. It is also affected by the experience of the photographer. Experienced photographers will often take a series of images to avoid media opacities and, by ‘jig-sawing’ the images together, good clear coverage of the retina can be obtained

There are definitions that enable a grader to decide whether an image can be safely graded. Since the introduction of the common pathway an image is now considered to be either ‘Adequate’ or ‘Inadequate’.

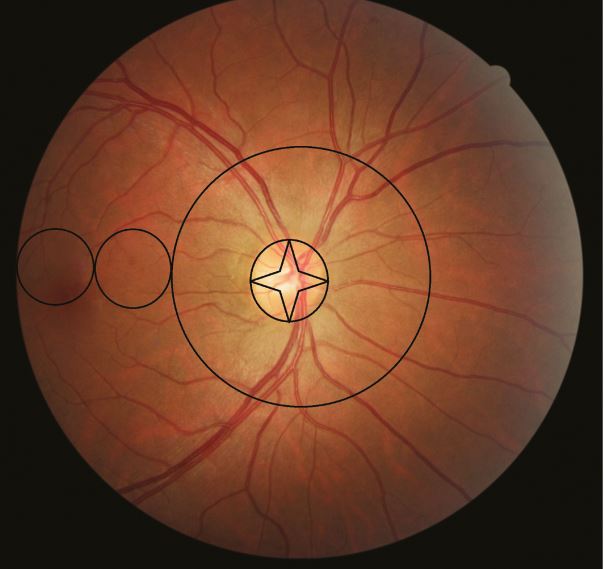

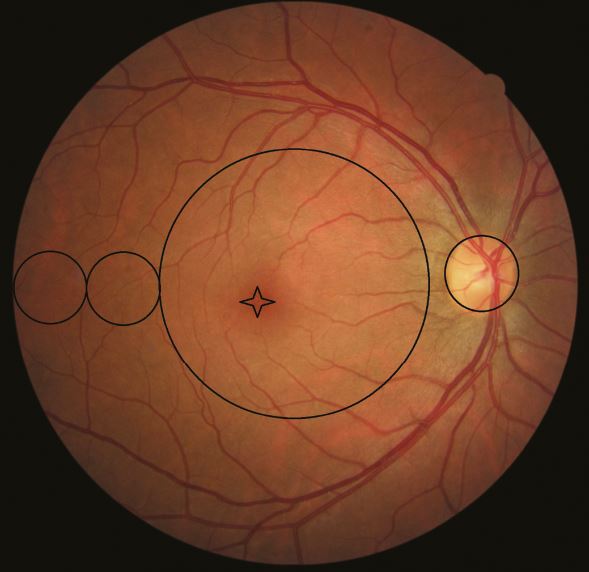

Photographers must capture 2x nominal 45º fields per eye (1x fovea centred, 1x disc centred). A combined assessment of field position and image quality should be made for each eye. Images must be graded for diabetic eye disease only if the grader is confident the quality is sufficient. All grading must be performed by trained qualified staff.

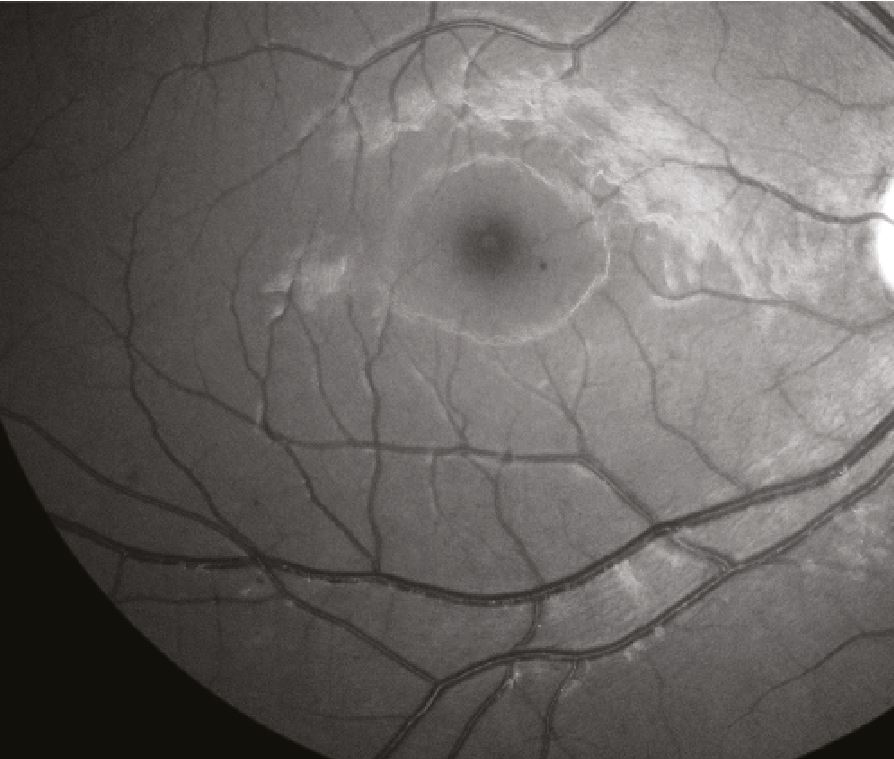

The definition of adequate is that both the centre of the fovea or the complete optic disc must be within a zone whose edge is two disc diameters (DD) from the edge of the image and centred on the image centre. Fine vessels must be visible within one DD of the centre of the fovea or on the surface of the disc. It is now possible for a screener to take a series of retinal images and for the grader to use a ‘jigsaw’ approach to ensure that the combined view is equivalent to the normal adequate fovea and disc centred approach (figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Disc-centred adequate image

Figure 5: Fovea-centred adequate image

An important qualification to this is that if sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy (STDR) can be detected on an otherwise inadequate series of images the quality should be considered as adequate and the patient referred to ophthalmology. This means that poor quality images should be studied especially carefully to ensure that no sight threatening lesions are visible. An important example of this is not to assume that a very hazy image is the result of cataracts as there is a possibility that the haze could be caused by a vitreous haemorrhage.

Assuring the quality of grading

Quality Assurance is embedded within the grading process. Good internal quality assurance (IQA) is the first step to ensuring patient safety and optimal performance of the screening programme.

National quality assurance processes will check that each programme has a good IQA process in place for the control of grading.

There should be continuous monitoring of all graders whatever their prior experience or expertise. If an individual grader needs help, the programme should determine any areas of need, set out an action plan for training and provide a supportive environment to return to independent working.

The national strategy to assure the quality of grading rests on the following principles:

- All programmes need to measure the same things so that comparisons are meaningful

- Grading quality must be measured against a consistent gold standard

- Training must be delivered uniformly across the grading workforce to ensure grading is the same in all services

As part of this national approach the screening programme will:

- Ensure clinical outcomes and grading performance are reported at the quarterly programme board meeting, and ensure staff are represented at these meetings

- Provide evidence that internal quality assurance systems are in place that are adequately monitored

- Regularly monitor and audit grading as part of the clinical governance arrangements, thus assuring the programme board of the quality and reliability of the grading

There are four areas that need to be monitored to ensure good quality accurate grading:

• Competent workforce

- This requires completion of an appropriate qualification. This was formally the City & Guilds qualification but that is currently being replaced by the Level 3 Diploma for Health Screeners

- Staff Personal Development plans

- A training plan with stages and overview and monitoring built into the grading software

- Protocols and Policies in place and adhered to

• Appropriate staff workload

- Regular monitoring of the grading queues

- Monitoring time taken to grade images

- Monitoring of monthly cumulative numbers grading

- Contingency plans for breaches in timescales

• Grading accuracy

- Participation in the online monthly test and training set

- Evidenced feedback on results – especially the specificity and sensitivity scores

- A regular review of inter-grader reports produced by the grader software

- 10% R0 Grader sample audit to compare with final outcome grades

- Achieving the minimum number of grades in a rolling year

- Feedback from arbitration grading

- Participation in regular multi-disciplinary training events

• Grading environment

- Monitoring of grader workstations

- Monitor light levels, noise levels and disruptions

Non-sight threatening Retinopathy grades

Normal R0

An image with no evidence of any lesions associated with diabetic retinopathy should be graded R0 (figures 6 and 7). However, other lesions which may or may not be sight threatening may be detected and should be referred according to local protocols. Some retinal appearances can ‘mimic’ some diabetic retinopathy lesions and it is important to be able to distinguish between features such as a pale spot being either a drusen or an exudate (particularly as some drusen are quite reflective) or myelinated nerve fibres appearing very similar to cotton wool spots especially if they are not adjacent to the optic disc. Comparing the image with previous encounters if they are available can help decide on the lesion. This is the stage at which patients and GPs should be encouraged to manage the diabetes as well as they possibly can. Evidence has shown that there is a glycaemic memory that affects disease progression so that a past period of poor diabetes control can influence progression at a future date.

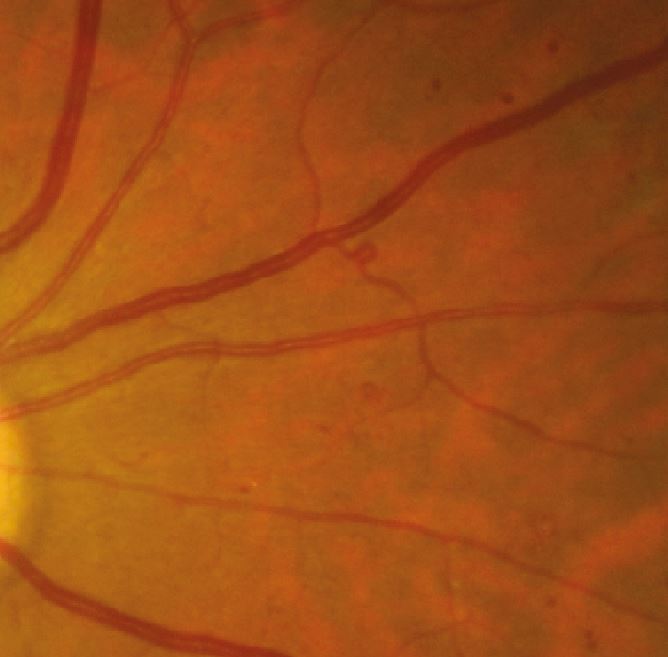

Figure 6: Disc-centred R0M0 image

Sometimes the grading may alternate between R0 and R1 over a series of screening encounters. For example, a small blot haemorrhage may absorb over time and no longer be visible on a future encounter image of the same retinal field. This is due to the fact that healing processes are occurring alongside the disease processes. In the London North East programme, we do mention this in the letter to both the patient and GP to avoid confusion and the possibility that the patient thinks a mistake in the grading has been made.

Figure 7: Fovea-centred R0M0 image

Background R1

Figure 8: R1M0 retina showing microaneurysms

The earliest stage of visible diabetic retinopathy is graded R1 and is labelled ‘background retinopathy’ (figures 8 and 9). This is an indication there are microvascular changes now present within the retina and optimal control of blood glucose and blood pressure are the primary management strategies used by the GP or Diabetes Specialist responsible for the patient’s diabetes.

Figure 9: Red free image of R1M0 retina showing microaneurysms

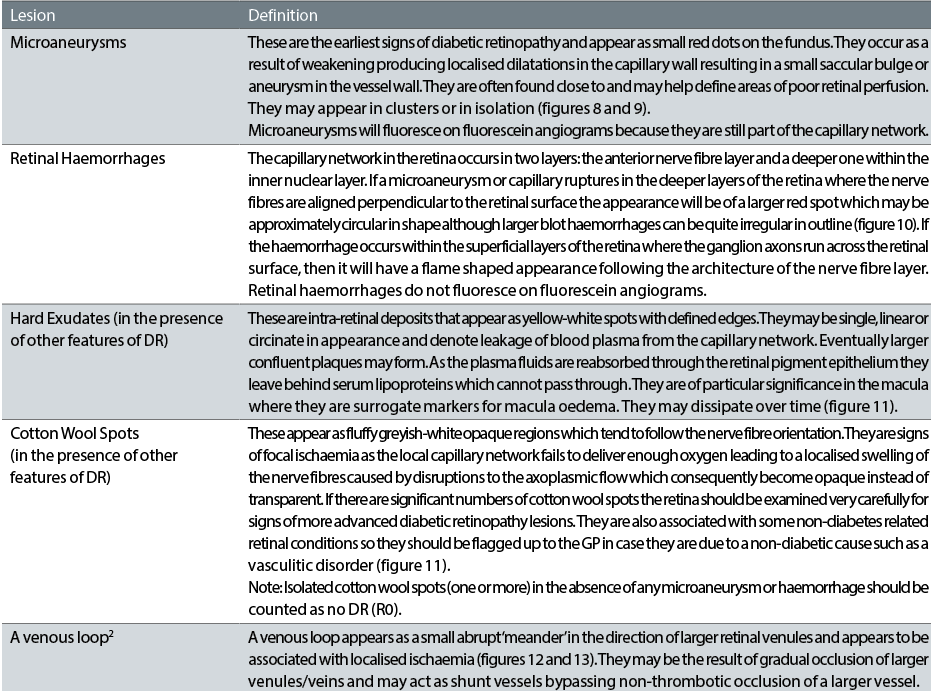

The main lesions associated with this level are shown in table 2.

Table 2: Lesions associated with background retinopathy

Table 2: Lesions associated with background retinopathy

Background diabetic retinopathy is not in itself sight-threatening and does not require referral to ophthalmology. It is, however, an indicator of early microvascular disease and patients should be advised to look at their diabetes and blood pressure control. This may be a good time to suggest to both the patient and GP that a review of the diabetes management plan is advisable. Management is annual recall to diabetic eye screening.

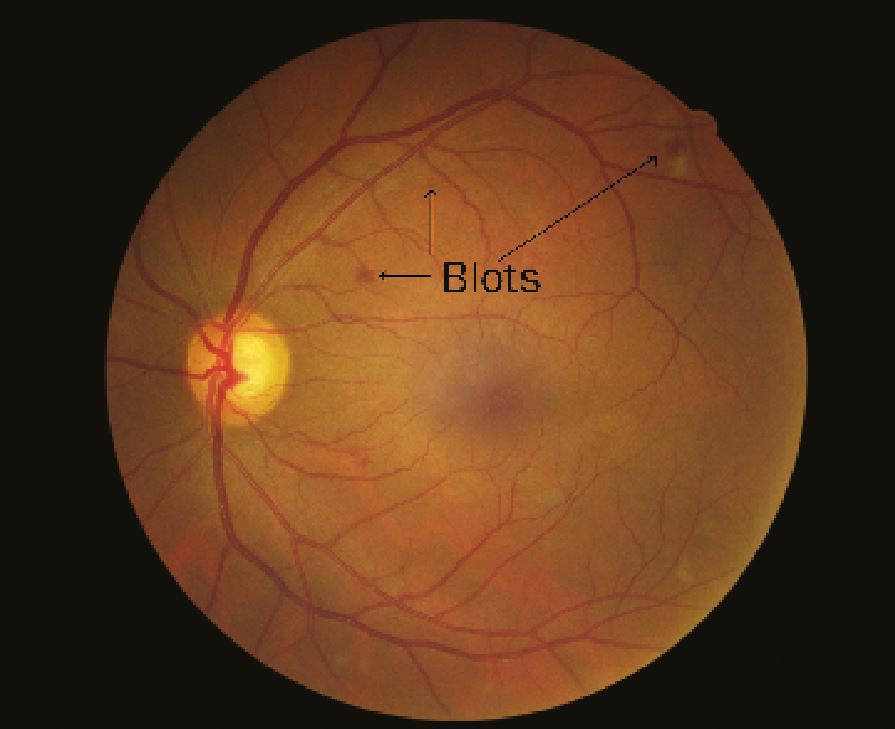

Figure 10: R1M0 retina with blot haemorrhages marked

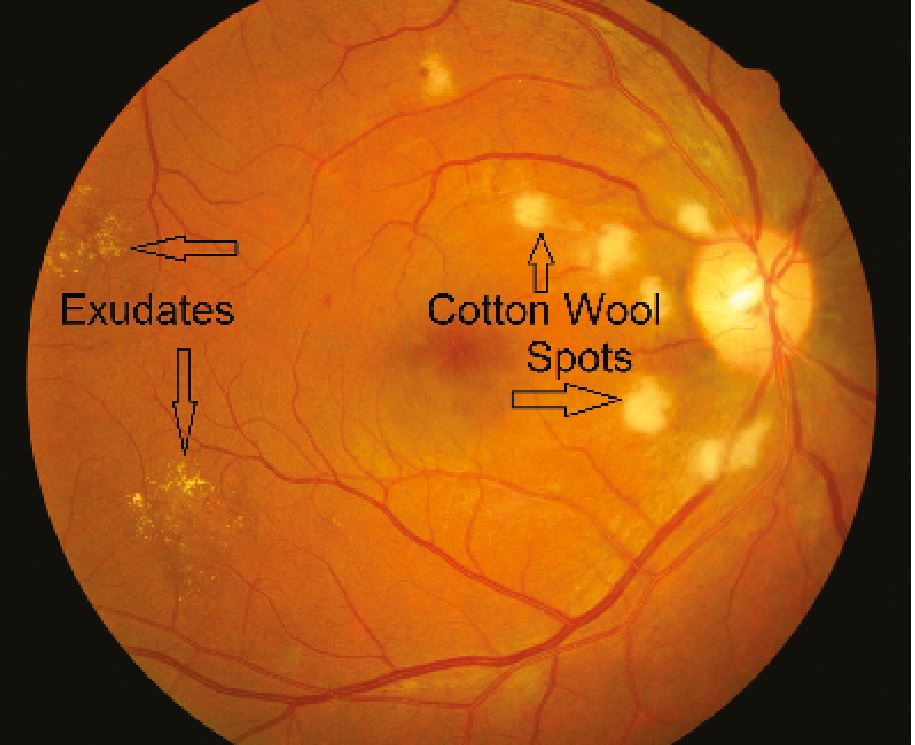

Figure 11: R1M0 retina showing distinction between exudates and cotton wool spots

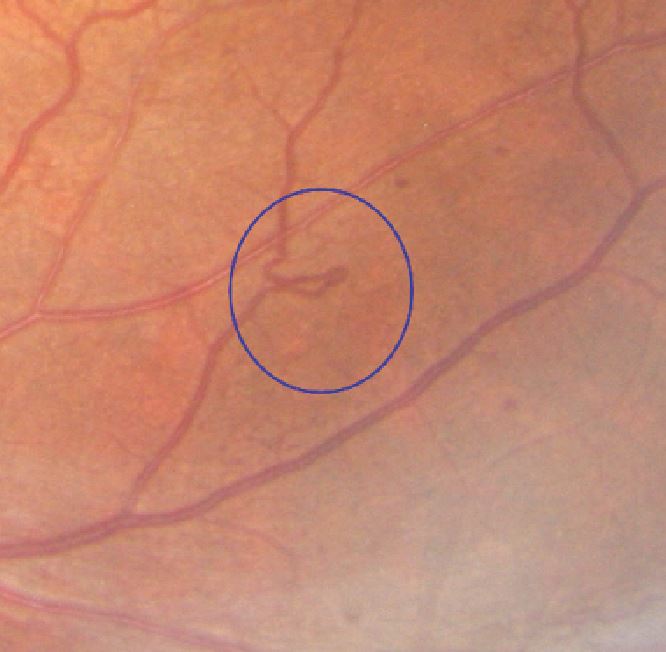

Figure 12: R1M0 retina with venous loop

Figure 13: R1M0 retina with venous loop (circled)

A note of caution: All these features may also be present in sight-threatening retinopathy so a careful study of the retinal images is important, especially as the number of these lesions increase.

Peter Mitchell is senior optometrist grader London North East DESP

References

- Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: WHO; 1968. Available from www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/4/07-050112BP.pdf

- Diabetic Eye Screening Revised Grading Definitions Version 1.3, 1 November 2012. Available at http://bmec.swbh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Diabetic-Screening-Service-Revised-Grading-Definitions-November-2012.pdf