At a first look, optometry and psychiatry are at opposite poles of healthcare. Nevertheless, knowingly or unknowingly, most optometrists will deal with individuals that are suffering from various psychological or psychiatric disorders. They will examine such patients for common ocular conditions, or for eye pathologies that are either a direct consequence of certain mental condition or of their treatments. In addition, visual impairment or ocular diseases that lead to disability, could have a disastrous effect on the patient’s wellbeing, often leading to psychological distress and even mental disorders. This series will offer only a glimpse into the many links between optometry and psychiatry. This first article will consider the psychiatric and psychological impact or eye disease and its treatment. The second article will consider psychiatric disorders with ocular consequence.

Diseases Causing Visual Impairment

Visual impairment is a common problem encountered in optometric practice and it affects patients of different ages and backgrounds. Worldwide, it is estimated that 253 million people live with vision impairment, with over 36 million being completely blind and 217 million suffering from moderate to severe vision impairment.1 Visual impairment can have severe effect on the patient mental wellbeing and below we discuss two of these possible consequences.

There are a large number of ocular diseases causing visual impairment; however, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy are the most common visual loss-causing diseases seen by the optometrist. Beside their ocular consequences, these diseases may also affect the patient well-being. In addition, low-vision patients often also suffer from other systemic diseases, which together with the visual impairment, may lead to a large variety of social problems, such as physical dependency, loneliness, social isolation, and often poverty. Sadly, elderly people usually accept all of these as part of the ‘natural part of ageing’. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that a large number of patients affected by AMD suffer indeed of very significant psychological distress, with a large number being diagnosed with depression (figure 1).

Figure 1: Many AMD sufferers have been diagnosed with depression

Female gender and social dependency increase even further the association between the two type of disorders.2 Moreover, in AMD patients in which ophthalmic treatments cannot help further, psychological support is an important management option and the optometrists and ophthalmologists should be aware of these possibilities and refer accordingly.

Visual hallucinations are another common complaint reported by visually impaired patients, in 10-40% of cases. In 1769, Charles Bonnet, a Swiss scientist, described the case of his grandfather who had his cataract removed at the age of 78. Subsequently, at the age of 89, he started having visual hallucinations consisting of different coloured and dynamic objects and people. Moreover, Charles Bonnet himself experienced the same phenomena towards the end of his life.3 Later all these symptoms were termed as the ‘Charles Bonnet syndrome’ (CBS). It is estimated that approximately 10% of all visually impaired patients will experience visual hallucinations as long as they have a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/36 or less. Charles Bonnet’s syndrome is characterised by the following clinical features:4

- Variable onset of highly organised visual hallucinations.

- The visual hallucinations are initial simple and elementary forms and then progress to more complex images. They tend to occur periodically or almost continuously.

- The hallucinations appear in the real world, are bright, coloured (as in AMD) or black and white (as in glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy), are usually animated and are outside of the patient’s control.

The explanation for the occurrence of Charles Bonnet syndrome in visual impairment patients is still under investigation. However, it seems that various stages of processing from retina to visual cortices, are involved.5 Indeed, an interruption on the normal visual pathway results in an increase in the spontaneous neural activity. Moreover, as part of the normal ageing process, the cortical inhibition decreases. Therefore, visual hallucinations may be the result of the complex interaction between increased spontaneous neural activity and loss of cortical inhibition. The visual cortex also has complex interconnections and a pathological increase in activity is widespread. Loneliness, shyness and use of topical beta-blockers, have also been implicated in the aetiology of this syndrome.

The hallucinations are brief and as the patient becomes accustomed to the vision loss, their frequency decreases. The first psychological reaction to visual hallucinations is complex and usually positive. The patients report surprise, curiosity and amazement and only very rarely, fear. Later, however, the embarrassment and fear that they may be losing their sanity make these persons very shy in reporting such symptoms. Only a very open and strong relationship with their physician helps them overcome this inhibition.

When dealing with a patient suffering from visual hallucinations a quick intervention is needed from a multi-disciplinary team, to include the optometrist for visual interventions:6

- Improve patient’s visual acuity and his or her physical condition

- If in doubt, replace medication such as beta-blockers

- Psycho-education: reassure the patients that they are not losing their sanity and teach them how to cope emotionally with the hallucinations

- Help patients to decrease their social isolation

- Use different techniques of relaxation

- Teach the patient techniques to stop hallucinations, such as: closing and opening the eyes, looking or walking away, approaching the hallucination, visual fixation on the hallucination, increasing the light, concentrating on something else, trying to hit the hallucination, shouting at the hallucination, etc.

Other ocular disorders with psychiatric consequences

There are a number of sight-threatening conditions known to have a strong association with psychiatric status. These are considered here.

Retinitis pigmentosa

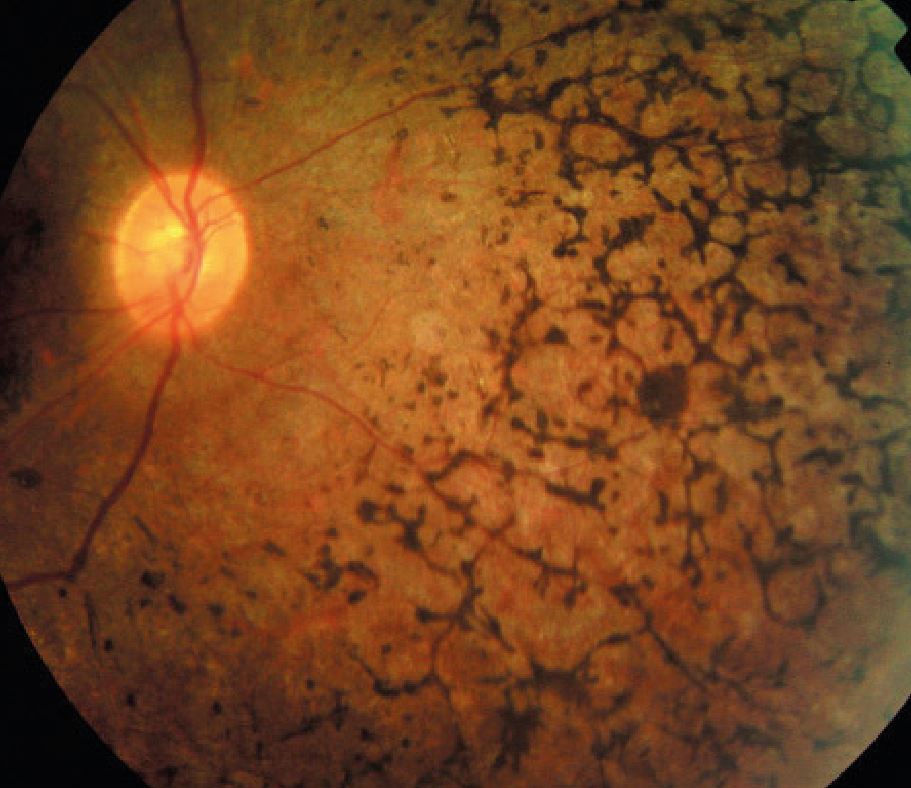

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) represents a group of hereditary diseases characterised by degeneration of photoreceptor cells and progressive loss of visual function (figure 2). The general prevalence of the disease is 1 in 4,000 people worldwide and it is an important cause of visual impairment and blindness by the age of 60. A number of inherited conditions are associated with RP, including abetalipoproteinemia, Refsum’s disease, Friedreich-like ataxia, Laurence-Moon-Bardet-Biedl syndrome and Usher’s syndrome. Almost all these diseases include some degree of neurological implications or mental retardation. However, the focus of this chapter will be psychiatric changes that occur in Usher’s syndrome.

Figure 2: Retinitis pigmentosa

Usher’s syndrome is characterised by the coexistence of progressive pigmentary retinopathy, congenital sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction. There are three types of Usher’s syndrome: type 1, characterised by profound congenital deafness and vestibular ataxia; type 2 in which the hearing loss is mild and non-progressive; and type 3, with progressive hearing loss.

Patients suffering from Usher’s syndrome can sometimes exhibit psychotic symptoms. Links between the genes responsible for schizophrenia (described below) and those for Usher’s syndrome have been implicated as possible causes for this association. It has also been suggested that the psychotic breakdown in patients suffering from Usher’s syndrome could be related to stress induced by the physical and social handicaps.7 Other researchers have purposed a neuropathological explanation for the coexistence of Usher’s syndrome and schizophrenia; according to this theory it seems that patients with Usher’s syndrome have global anatomical cerebral and cerebellar degenerations that could lead to the observed psychotic changes.7

Ocular tumour and trauma

Ocular tumours and trauma often result in facial disfigurement and can cause psychological disorders in those who have suffered them. There are also currently many cases of ex-soldiers that suffered facial and ocular trauma during various battles and the optometrists are very likely to encounter such patients.8 Disfigurement affects not only patient’s self-image and sense of attractiveness but also his or her social and occupational roles and interactions.9 The most common reactions are depression, acute stress reactions, anxiety and personality changes. When the facial disfigurement is the result of a trauma the patient may experience the so-called ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ (PTSD), a neurophysiological disease which occurs in 20% to 30% of people exposed to traumatic stress.

The ophthalmologist and optometrist have an important role in the physical but and psychological recovery of these individuals. However, PTSD might often go unrecognised by eye care providers. Nevertheless, whenever it is suspected that a patient might be suffering from PTSD, it is important to assure that a multidisciplinary approach is given to the case. Work should be performed in collaboration with psychologists and social workers in order to establish the best care for the patient. As part of this type of team, the optometrists can play a crucial role in improving not only the vision but also the wellbeing of these patients and their families.

Dry eye

Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial, potentially very serious and disabling condition that in severe cases can be associated with depression, anxiety, PTSD and sleep disturbances.10 It has been suggested that common risk factors, such as female gender and a high omega-6/omega-3 ratio could increase the likelihood of these two types of disorders co-existing.11 In addition, medications for various psychiatric disorders, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI, see below), have been associated with DED. Practitioners should investigate further the medical history of patients with DED unresponsive to conventional treatments and work together with the other healthcare teams involved in the management of those patients.

Keratoconus

Keratoconus, a rare progressive corneal ectasia associated with myopia, astigmatism and scarring, has also anecdotally been associated with peculiar personality traits such as hyperactivity, suspiciousness, distrust, anxiety, demanding and paranoid behaviour, which make them sometimes uncooperative, and non-compliant with treatment plans.12 Ophthalmologists and optometrists working with this type of patient believe this unique personality is the result of the complex psychosocial development of the individual in the period that keratoconus first manifests itself, usually around puberty. Fear of blindness and high level of negative emotions in a young adult could have disastrous effects on his/her personality. A case of psychosis has been reported in a patient suffering from keratoconus13 but there is no clear evidence of linkage between the two types of disease.

Psychiatric consequences of ophthalmic medication

The most common way to treat eye diseases is by using a large variety of topical administrated solutions, suspensions, gels or ointments. These drugs act primarily at eye level; however, drugs passing into the nasolacrimal duct can enter the systemic circulation either via the nasal mucosa or from the gastrointestinal tract after ingestion, and can cause a multitude of systemic side-effects. Depression, psychosis, confusion, hallucinations and other complaints of psychiatric nature are sometimes simply the result of topically administered eye drops and unfortunately the physician can very often overlook the link between mental complaints and, for example, glaucoma treatment. These patients could receive unnecessary psychiatric referral and treatment, whereas simple withdrawal of the drug results in disappearance of these effects. To minimise psychiatric effects, it is recommended the patient is advised to apply gentle pressure on the canaliculi of each eye, immediately after the administration of the drug, or to simply close the eye for five minutes after the instillation. We will now consider five groups of drugs with psychiatric influence.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are possibly the most commonly prescribed drugs in medicine. They were first introduced to ophthalmology in the 1950s, first as systemic medication and then as drops, ointments and solutions for local injections. Their main effect is anti-inflammatory, accomplished via a large variety of mechanisms such as vasoconstriction and reduction of vascular permeability, membrane stabilisation and stabilisation of mast-cells and basofils, suppression of lymphocyte proliferation and mobilisation of PMNs, etc. Systemic side effects of corticosteroids have been reported with the oral and parenteral forms of administration; however, systemic absorption of topically administrated corticosteroids is important. Depression, mania, psychosis, and other psychiatric disorders have all been reported after topical, long-term corticosteroids therapy.

Timolol

Timolol was introduced for the treatment of glaucoma in 1977 and since then it has been an essential part of the management of the disease. Only about 1% of topically administrated timolol is absorbed into the eye leaving the other 99% available for systemic absorption. Because the drug is absorbed directly into the venous circulation it bypasses the hepatic detoxifying metabolism, thus increasing the risk of systemic toxicity. Approximately 10% of the glaucoma patients treated with timolol can experience different psychiatric problems such as fatigue, depression, dissociative behaviour, memory loss, paranoia, confusion, hallucinations and psychosis.14 Psychiatric side-effects following betaxolol therapy have also been reported.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAI)

CAI are another class of drugs used in ophthalmology as intraocular pressure-lowering agents. Initially administrated systemically as acetazolamide, CAIs have also been developed as topically active forms under the names of dorzolamide and brinzolamide. Carbonic anhydrase is a widely distributed enzyme that catalyses the production of H2CO3 from CO2 and H2O as well as the degradation of H2CO3 to CO2 and H2O throughout the body. The inhibition of this enzyme carries potentially numerous side effects. Among them, tiredness, lack of appetite and somnolence may be appreciated as depression; however, true depression and agitation have also been reported.

Anticholinergic medications

Atropine, homatropine, scopolamine and cyclopentolate are often used in ophthalmology as mydriatic and cycloplegic drugs. They act by blocking the cholinergic response of the iris sphincter and ciliary muscle. Most of the drug is destroyed by hepatic metabolism; however, 13% to 50% is excreted unchanged in the urine. Consequently, people with renal diseases may be at risk of systemic toxicity after administration of anticholinergic drops. Visual and auditory hallucinations, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, confusion, memory loss, delirium and paranoia have all been reported in association with anticholinergic systemic and topical therapies. These possible effects are of an increasing importance since the number of surgical refractive correction procedures for myopia and hyperopia are increasing, while cycloplegic refraction will naturally be performed in more such cases. Refractive surgery teams should, therefore, be aware of the toxic effects of cycloplegic drugs such as cyclopentolate, in certain patients.15

Sympathomimetic eye drops

These drugs have a large utilisation in ophthalmology. Some agents are used in the treatment of glaucoma, while others are used as mydriatics, anaesthetics, and vasoconstrictors. It has been reported that some of these agents may cause anxiety, depression, hallucinations and paranoia.

In Part 2, we will discuss specific psychiatric disorders with ocular consequences.

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

References

- Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, et al. Vision Loss Expert Group. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017; e888-97.

- Ryu SJ, Lee WJ, Tarver LB et al: Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life in Age-related Macular Degeneration Based on Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Korean J Ophthalmol 2017; 5: 412-423

- De Morsier, G. (1967). The Charles Bonnet Syndrome: visual hallucinations in the aged, without mental deficiency the Charles Bonnet Syndrome: visual hallucinations in the aged, without mental deficiency. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, 2(5), 677-702.

- Damas-Mora J, Skelton-Robinson M, Jenner FA. The Charles Bonnet’s Syndrome in perspective. Psychol Med 1982; 12: 251-261

- Bernardin F, Schwan R, Lalanne L, et al. The role of the retina in visual hallucinations: A review of the literature and implications for psychosis. Neurosychologia 2017; 99: 128-138

- Domanico D, Fragiotta S, Cutini A et al. Psychosis, Mood and Behavioral Disorders in Usher Syndrome: Review of the Literature. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol 2015; 4: 50-55

- Trachtman JN. Post-traumatic stress disorders and vision. Optometry 2010; 81: 240-252

- Lubkin V, Sloan S. Enuclation and psychic trauma. Adv Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 1990; 8: 259-262

- Egan RA, LaFrance WC Jr. Functional vision disorder. Semin Neurol 2015; 35: 557-563

- Han SB, Yang HK, Hyon JY, Wee WR. Association of dry eye disease with psychiatric or neurological disorders in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging 2017; 12: 785-792

- Kim KW, Han SB, Han ER, et al. Association between depression and dry eye disease in an elderly population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52:7 954-7958.

- Giedd KK, Mannis MJ, Mitchell GL, Zadnik K. Personality in keratoconus in a sample of patients derived from the internet. Cornea 2005; 24: 301-307

- Rudisch B, D’Orio B, Compton MT: Keratoconus and psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:5.

- Bali SJ, Parmar T, Arora V, et al. Evaluation of major depressive disorder in patients receiving chronic treatment with topical timolol. Ophthalmologica 2011; 226: 157-160

- Mirshashi A, Kohnen T: Acute psychotic reaction caused by topical cyclopentolate use for cycloplegic refraction before refractive surgery. Journal Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:1026-1030.