In part one of this discussion we looked at the psychological impact of eye diseases and their treatments (Optician 24.11.17). It is also important to recognise the significant ocular impact of a range of psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, many drugs used to treat psychiatric states have ocular consequences of which practitioners need to be aware.

Psychosis

‘Psychosis’ is a term used to describe a radical change in one’s personality, associated with distorted or diminished sense of reality. Psychotic symptoms are often part of the clinical presentation of more general medical disorders, or may occur as an effect of various medications. If unrecognised, these patients can be a very big challenge for any practitioner. An incorrect approach could lead to mistakes in patient diagnosis and management.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia represents a serious mental illness characterised by hallucinations, delusions, disorganised speech and movements, ‘flat’ emotions, and impaired memory. The change in personality seems to occur during adolescence. However, subtle psychological/neurological symptoms may sometimes be present during childhood, as shown in table 1. Various genetic and environmental factors that are able to induce abnormalities of the brain’s chemistry, anatomy and development have been implicated in the aetiology of this disease.

Table 1: Common psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia (adapted from the American Psychiatric Association1)

Oculomotor dysfunctions are often associated with schizophrenia diagnosis. Impaired tracking with poor smooth pursuit and abnormal saccadic movements were observed in one study, independent of the usage of antipsychotic drugs.2 Moreover, these abnormalities were also present in the first-degree relatives of the patients investigated, suggesting that this deficit could be used as a risk marker for these types of diseases. It has also been suggested that a neurodevelopmental defect during the embryo development could also account for the visual anomalies in schizophrenia.4

Patients that have schizophrenia may also have poor hygiene and use toxic substances such as smoking, alcohol and drugs. This can lead to poor general health and patients may present with diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis, Aids and other sexually transmitted pathology.1 Moreover, uncorrected refractive errors, ocular trauma and infections, as well as blindness, can occur with a higher incidence in these individuals.3 Therefore, these patients should be screened regularly for eye diseases and/or changes in refraction and proper intervention should be applied without delay. Visual and auditory hallucinations are also part of the clinical picture of schizophrenia.

Figure 1: Corneal deposits

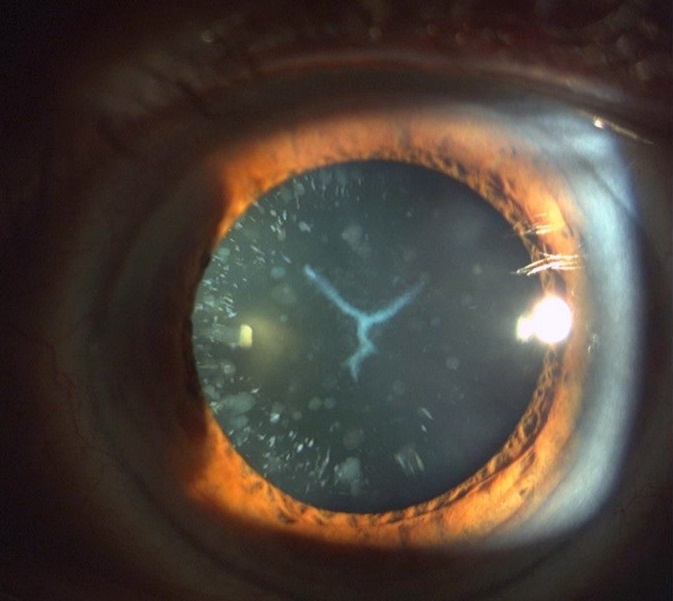

Antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia have multiple ocular side effects. Chlorpromazine, a neuroleptic drug, is the most well-known antipsychotic agent used but this can cause ocular side effects such as decreased vision, accommodation problems, corneal deposits (figure 1), cataract (figure 2), pupillary abnormalities, and retinopathy. Most of these effects are the result of pigmentary deposits and blood dyscrasias.4

Figure 2: Cataract

Wilson’s Disease

Wilson’s disease represents a systemic disorder that is characterized by liver failure, haemolytic anaemia, and neurological defects (balance disturbances, abnormal reflexes and speech, gait disturbances, tremors or chorea). It is the result of an abnormal copper metabolism and accumulation of this substance all over the body. Psychiatric abnormalities such as depression and psychosis can also be part of the clinical presentation of this disease. Ocular involvement in Wilson’s disease is represented by the Kayser-Fleischer ring, which denotes neurological impairment and consists of copper deposition in the cornea. It presents as a greenish or golden brown ring around the cornea. About one in five patients suffering from this disease also present with sunflower cataract.

Dementia

It is estimated that 850,000 people are living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the UK, with numbers expected to quadruple by 2040. Abnormalities of the retinal nerve fiber layer,5 optic nerve head (ONH) as well as retinal cell loss6 have already been reported in AD patients. Moreover, patients with AD also display retinal microvascular structural variation that mirror changes at the cerebral level.7 A large variety of ocular disorders can, in fact, be more common in patients suffering from AD. A complete review on dementia and associated ocular problems was published in Optician in 21.04.2017.

Autistic spectrum disorders (ASD)

Autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) represent a common pathological neuro-developmental entity characterised by lack of social interaction, abnormal communication and limited language as well as by repetitive, stereotyped activities/behaviours. This spectrum includes conditions such as autism, Asperger’s syndrome, Rett’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD) and pervasive developmental disorder (PDD). These disorders affect over 700,000 people in the UK (the National Autistic Society, www.nas.org.uk). ASD is usually managed by healthcare providers, from various disciplines, from neurologists, psychiatrists, behavioural paediatricians, psychologists, speech therapists, optometrists and ophthalmologists among others. The inclusion of this entity in this particular article is based on the fact that the medications given for these disorders belongs to psychiatric drugs category.8 In addition, the people on the autism spectrum suffer from mental disorders such as depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disease in a higher proportion than general population. The ocular features associated within this category of disorders include atypical gaze (side viewing), difficulty in maintaining visual attention, and difficulties with face processing. These patients may also experience scotopic sensitivity, abnormal movement of text, difficulty with high contrast, difficulty maintaining attention, and tunnel vision. More typical visual defects such as refractive errors, strabismus, and oculomotor dysfunction can also be present. Moreover, autism can be diagnosed more often in blind or visually impaired children.9

Due to the extensive behavioural problems, patients suffering from ASD can be a challenge for any healthcare professional. Most of the time, inability to perform well with tasks such as writing or reading are labelled as part of the disorder. However, it is possible that adequate eye examination will detect correctable vision problems that can be easily addressed, resulting in great benefits for the child’s behaviour and performance.

Psychiatric medication with ocular side effects

In this particular article, only the ocular effects of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs are presented.

Antipsychotic drugs

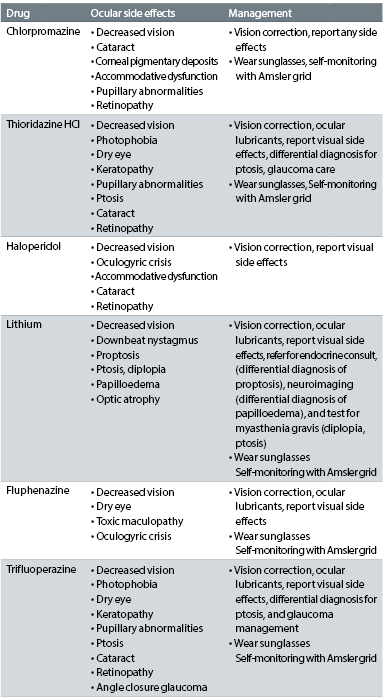

During treatments with these type of drugs, there are many potential toxic effects with liver being the most affected, followed by the eye. Maculopathy 10, oculogyric crisis 11, nystagmus, proptosis, and papilloedema 12-13, ptosis and angle-closure glaucoma, are all possible side effects of antipsychotic drugs. These are summarised in table 2.

Table 2: Ocular side effects of the most common antipsychotic drugs (adapted from the American Optometric Association)1

Other antipsychotic drugs, such as clozapine, risperidone, and olanzepine have been mostly associated with the side effect of oculogyric crisis 14-15, which is an ocular dystonia whereby the eyes deviate upwards; the crisis is associated with autonomic symptoms such as pupil dilation, salivation, catatonia, high blood pressure, as well as with depression, obsessions and even violence.

Antidepressants

Depression represents a serious mood disorder, with severe symptoms that affect emotions, cognition, behavior and physical well-being. It has a large variety of triggers and suffering from a physical disability, such as low vision, can also contribute to the onset of depression.

There are many antidepressants on the market, almost thirty different kinds grouped five main types, in five categories:

- SSRIs (Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)

- SNRIs (Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors)

- NASSAs (Noradrenaline and specific serotoninergic antidepressants)

- Tricyclics

- MAOIs (Monoamine oxidase inhibitors)

Most of the ocular side effects of these medicines are not explained in details, but are mostly described as either ‘visual disturbances’ or ‘visual symptoms’ 16.

SSRIs are mostly associated with dry eye, possibly due to altered levels of serotonin that can affect the sensitivity thresholds of corneal nerves, resulting in disruption to tear film 17. They also can precipitate acute angle closure glaucoma attacks. Therefore, when examining a patient under treatment with antidepressants, particular attention should be paid to severity of dry eye symptoms and possible danger of angle closure. In addition, prior to prescribing SSRIs, the physicians should be aware of the patients’ risk for either of the above possible ocular complications. A good interprofessional communication is, therefore necessary between optometrists, ophthalmologists, GPs and psychiatrists. Tricyclics are also on the list for high risk of causing acute angle closure attacks.

Other side effects associated with antidepressants are: blurred vision, mydriasis, accommodation abnormalities, ocular pain, photophobia, ocular hemorrhages, anisocoria and diplopia.

Conclusion

When dealing with ophthalmic patients it is easy to forget that each person is unique, with special emotions and psychological needs. A disabling eye disease affects not only the patient’s self-image but also his or her entire family system and social life and, sometimes, may also trigger the appearance of a large variety of mental diseases. On the other hand, patients with pre-existing psychiatric disturbances may produce physical symptoms that could mimic some ophthalmic diseases. Therefore, treatment and rehabilitation of these patients should address equally both the disease and psychological maintenance factors. Optometrists should work as part of the multidisciplinary teams involved in the management of such patients.

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

References

- American Psychiatric Association: Part B: Background information and review of available evidence. IV. Disease definition, natural history and course and epidemiology. In: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia, 2nd ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2004:40.

- Mayhofer I, Steffens M, Faiola E et al. Combining two model systems of psychosis: The effects of schizotypy and sleep deprivation on oculomotor control and psychotomimetic states. Psychophysiology 2017; 54: 1755-1769

- Smith D, Pantelis C, McGrath J, Tangas C, Copolov D: Ocular abnormalities in chronic schizophrenia: clinical implications. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1997; 31:252-256.

- Gagne AM, Hebert M, Maziade M. Revisiting visual dysfunctions in schizophrenia from the retina to the cortical cells: A manifestation of defective neurodevelopment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2015; 62: 29-34

- Danesh-Meyer HV, Birch H, Ku JY, Carroll S, Gamble G. Reduction of optic nerve fibers in patients with Alzheimer disease identified by laser imaging. Neurology. 2006;67:1852–1854.)

- Blanks JC, Schmidt SY, Torigoe Y, Porrello KV, Hinton DR, Blanks RH. Retinal pathology in Alzheimer's disease. II. Regional neuron loss and glial changes in GCL. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:385–395

- S Frost, Y Kanagasingam, H Sohrabi, J Vignarajan, P Bourgeat, O. Salvado, et al Retinal vascular biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of Alzheimer’s disease Transl Psychiatry, 3 (2013), p. e233

- Rettew D. ABC of Child Psychiatry: Is autism a mental illness? Psychology Todat Oct 2015. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/abcs-child-psychiatry/201510/is-autism-mental-illness

- Black K, McCarus C, Collins ML, et al. Ocular manifestations of autism in ophthalmology. Strabismus 2013; 21:98-102

- Lee MS, Fern AI: Fluphenazine and its toxic maculopathy. Ophthalmic Res 2004;36:237-239.

- Kazuhiko A: Psychiatric symptoms associated with oculogyric crisis: a review of literature for characterization of antipsychotic-induced episodes. World J Biol Psychiatry 2006;7:70-74.

- Bourgeois JA: Ocular side effects of lithium- a review. J Am Optom Assoc 1991;62:548-551.

- Lee MS, Lessell S: Lithium-induced periodic alternating nystagmus. Neurology 2003;60:344.

- Mendhekar DN, Duggal HS: Isolated oculogyric crisis on clozapine discontinuation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;18:424-425.

- Rosenhagen MC, Schmidt U, Winkelmann J, Ebinger M, Knetsch I, Weber F: Olanzapine-induced oculogyric crisis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:431.

- Richa S, Yazbek J. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents. CNS drugs 2010;24(6):501-526.

- Kocer E, Kocer A, Ozsutcu M, Dursun AE, Krpnar I. Dry Eye Related to Commonly Used New Antidepressants. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology 2015 Aug;35(4):411-413.