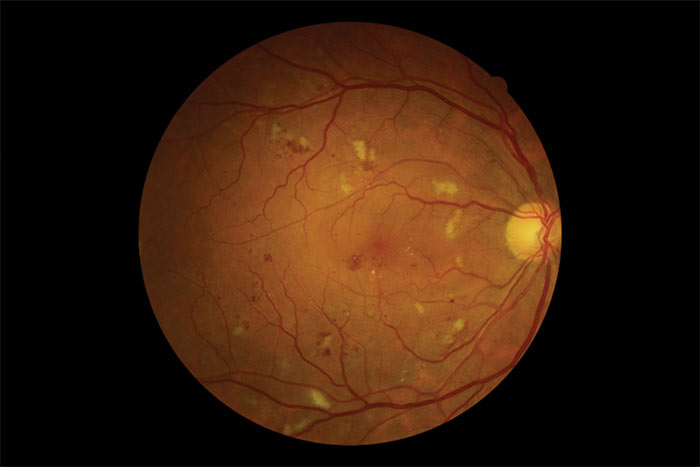

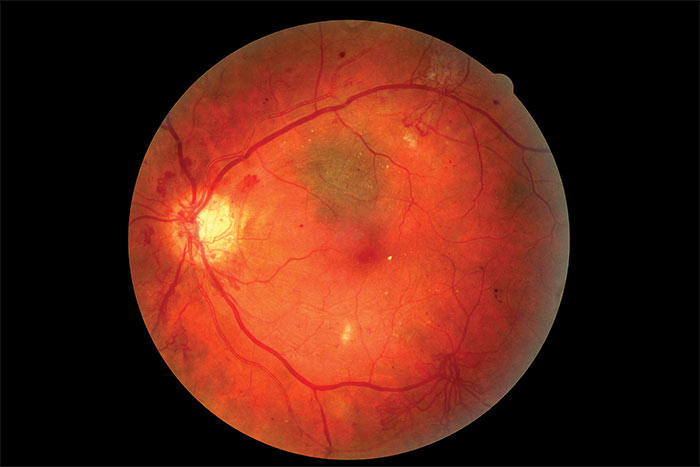

Figure 1: Multiple blot haemorrhage

Pre-proliferative Retinopathy R2

This is a clinically identifiable stage within the progression of retinopathy from background through to proliferative. As its name implies it is the stage that precedes and to some extent predicts future proliferative retinal changes if the diabetes is not well managed. It is graded R2 and labelled pre-proliferative retinopathy. Increasing signs of retinal ischaemia, sometimes local through to pan-retinal, and the associated vascular changes that accompany this, are the main features that classify this level of retinopathy. Progressive endothelial cell loss in the capillaries causes occlusion within the capillary network resulting in areas of chronic retinal ischaemia. As discussed in the R3 paragraph, this can progress quite quickly to proliferative retinopathy if not properly managed.

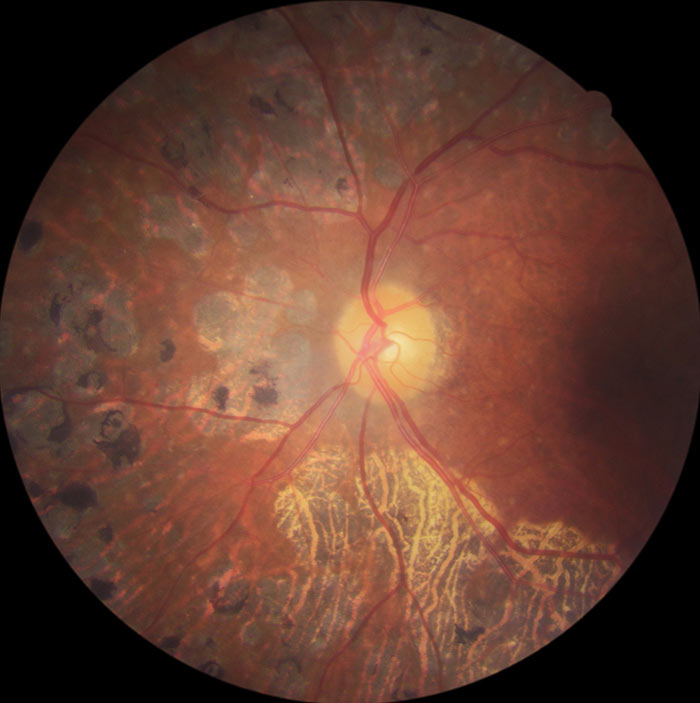

Figure 2: Multiple blot haemorrhage

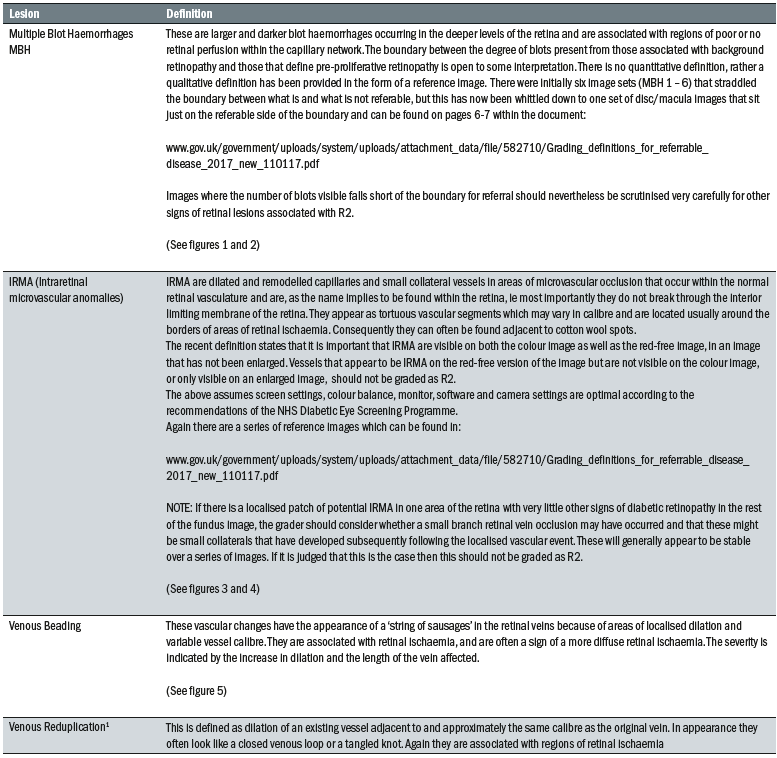

The main lesions associated with this level are outlined in table 1.

Table 1: Lesions associated with pre-proliferative retinopathy

Figure 3: Colour image showing IRMA

If an image is determined to be an R2 grade, then the patient should be referred to see an ophthalmologist within three weeks of their screening event and receive their first consultation within 13 weeks of the screening event. If the diagnosis is confirmed then management is generally medical, although in severe cases laser therapy is also an option. Regular follow ups within ophthalmology are usual. Aggressive management of blood pressure is important but care must be exercised in tightening control of the blood glucose levels, as too rapid an approach can result in a worsening of the retinopathy that may then progress to the proliferative stage. A steady approach over many weeks/a few months is often the preferred management plan,

Figure 4: Red free image showing IRMA

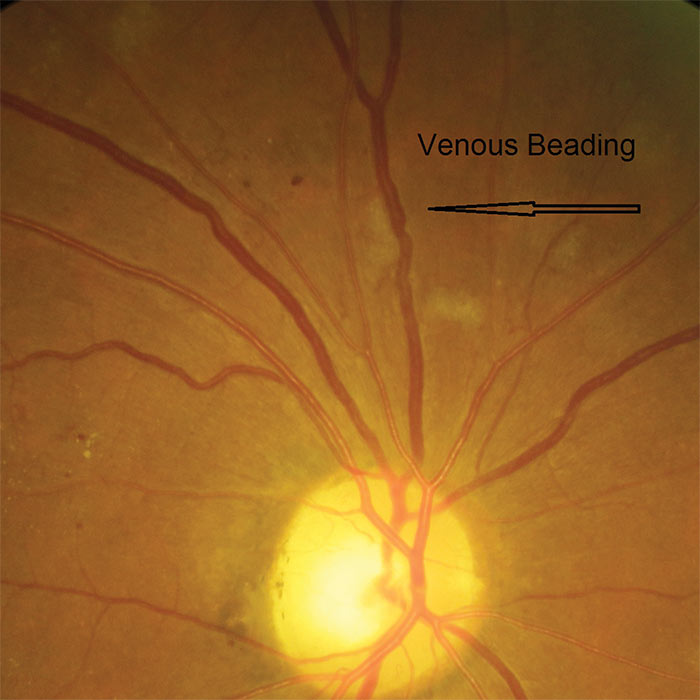

Figure 5: Venous beading

Active Proliferative Retinopathy R3A

The changes to the grading scheme as part of the introduction of the common pathway have resulted in two categories for R3 proliferative retinopathy. R3A indicates that the proliferative changes are active and require management. R3S indicates the phase after treatment for R3A when the retinal condition is considered by a medical retina specialist ophthalmologist to be stable (see next section)

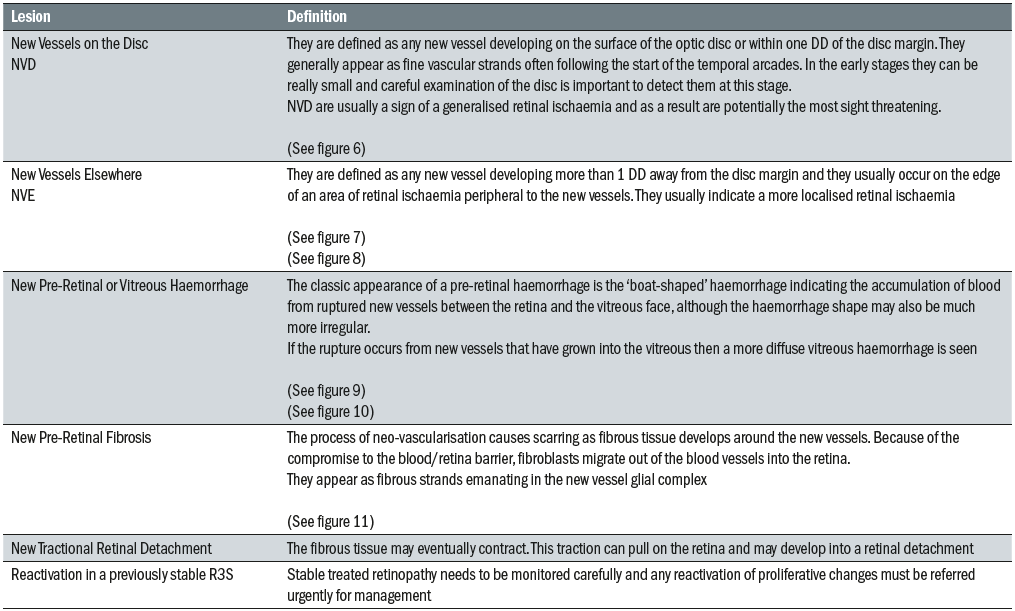

The following will be classed as R3A (active):

- Patients with newly presenting proliferative retinopathy

- Patients where previous treatment has not been deemed stable by the treating ophthalmologist

- Patients where new features indicating reactivation of proliferation, or potentially sight threatening change from fibrous proliferation, are seen with respect to a previously obtained reference image set.

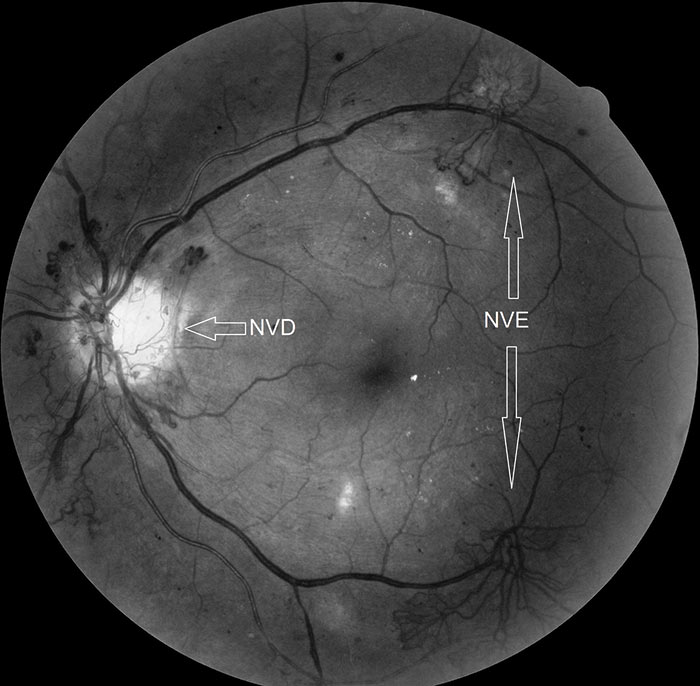

Figure 6: R3A with new vessels at the disc (NVD)

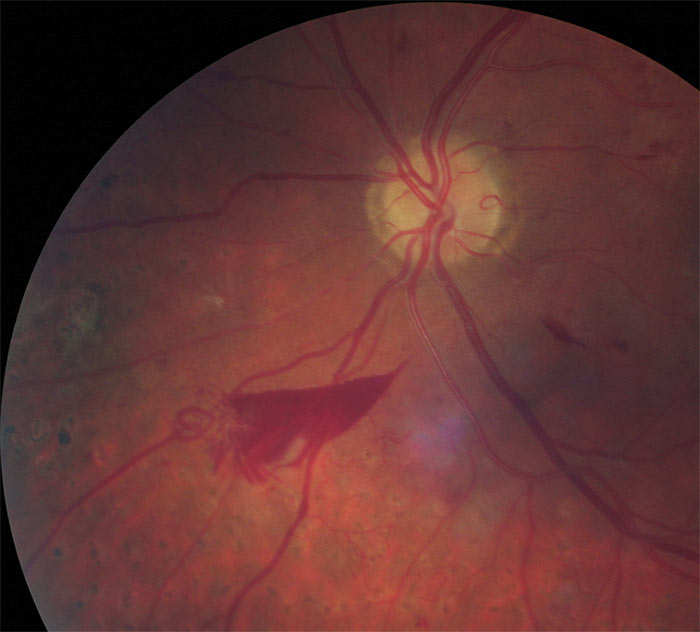

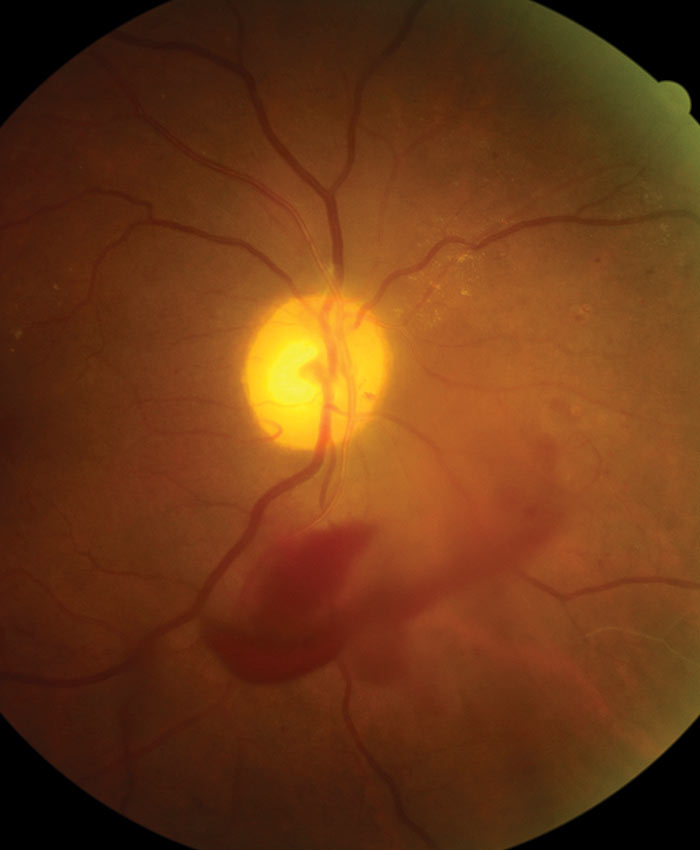

The definitive feature of the proliferative phase of diabetic retinopathy R3A is new vessels. These are fragile immature vessels that develop as a result of retinal ischaemia and follow on from the vascular changes of the pre-proliferative stage of retinopathy. They can grow on the disc (NVD), elsewhere on the surface of the retina (NVE) and on the iris (rubeosis). They are mediated by the release of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and other factors within the retina and this release is stimulated by hypoxic retinal tissue. New vessels are considered to be an attempt by the retina (doomed to failure) at revascularisation of the ischaemic areas. Unlike collateral vessels which redirect venous flow within the retina, new vessels are not remodelled existing vessels but are a new outgrowth from the circulation that have a random appearance with no obvious purpose to the direction they grow in. They often grow from the venous circulation so particular attention should be paid to inspecting the retinal veins across the whole image. They have a variety of different appearances, from small bud-like growths at vessel junctions to long strand like loops with circular frond like tips. They can be very obvious or very subtle so a careful analysis of the digital images must be made to ensure they are not missed. They develop within the vitreo-retinal interface with no support from the surrounding tissue and can grow into the vitreous body itself. Lacking the usual support of normal retinal vessels, the vessel walls are fragile and may rupture causing pre-retinal and vitreous haemorrhages. New vessels growing in the anterior chamber angle lead to an intractable rubeotic glaucoma.

Sometimes a grader will find that one eye shows proliferative retinopathy with little or no retinopathy in the other eye. This is highly indicative of a compromise to the retinal circulation in one eye and may indicate a systemic condition such as carotid insufficiency on that side of the head rather than as a result of poorly controlled diabetes. The features classifying R3A are outlined in table 2.

Table 2: Clinical features of R3A classified retinopathy

If proliferative retinal changes are noted and the image graded R3A an urgent referral to ophthalmology is generated. Cases should be referred within two weeks of the initial screening encounter and should be seen for a first consultation in ophthalmology within six weeks of the screening event. There are a range of management options now available to ophthalmologists managing proliferative retinopathy including pan retinal photo coagulation but discussion of this is beyond the scope of this article.

Urgent referral is crucial to the management of patients with proliferative retinal changes. To facilitate this, image triage within the screening pathway allows for rapid identification of potential R3A allowing for priority grading and fast track referral. However, if the new vessels are subtle and not detected at the primary grade there is a risk of them sitting in the grading queue and breaching the two week referral deadline so it is important that programmes tackle all the grading queues in a timely manner to avoid this happening.

Figure 7: Colour image of R3A with new vessels elsewhere (NVE)

Figure 8: Red-free image of R3A with new vessels elsewhere (NVE)

Figure 9: Pre-retinal haemorrhage

Stable Treated Proliferative Retinopathy R3S

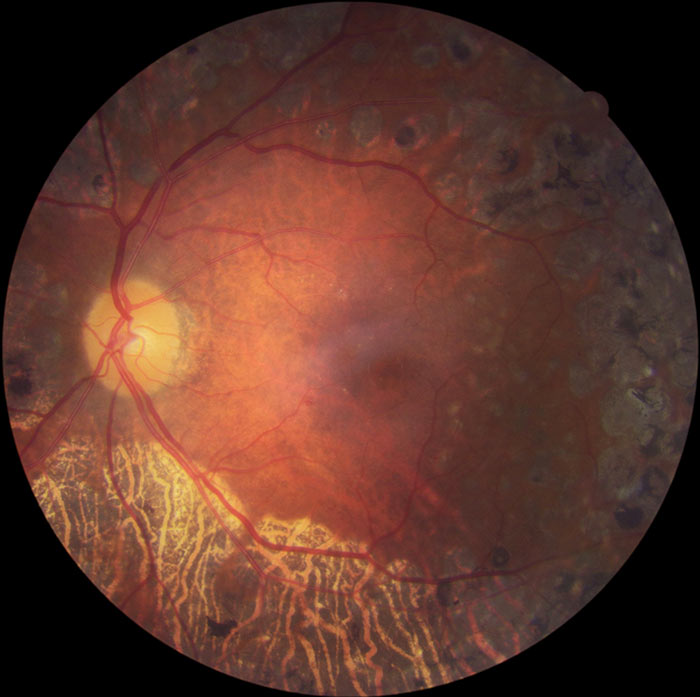

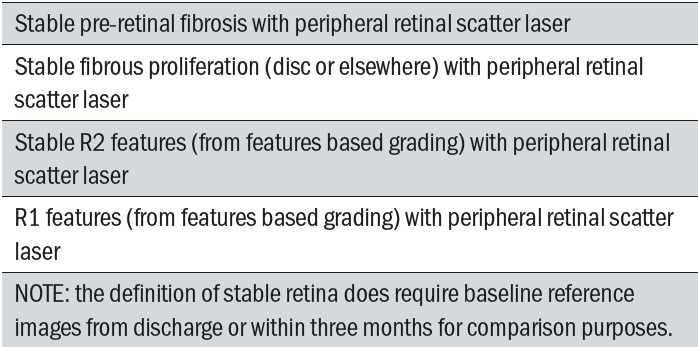

Stable treated proliferative retinopathy R3S is defined as retinal images with evidence of peripheral retinal laser treatment and with stable retina with respect to reference images taken at or within three months after discharge from the ophthalmology as ‘treatment completed’. These patients are then reviewed every six months within the digital surveillance pathway.

A Referral Outcome Grader will always be responsible for the decision as to whether the images indicate a stable retina. That decision is based on a known discharge from ophthalmology with an R3S Grade and baseline reference images used for future comparison. If there is any doubt, then the images should be graded R3A and the patient referred for an urgent review by an ophthalmologist. If there are no reference images available from ophthalmology discharge or soon after, then it may be necessary to re-refer the patient to acquire the essential reference images.

Figure 10: Vitreous haemorrhage

The split into R3A and R3S grades allows for urgent attention where proliferative disease is active and a robust monitoring pathway outside the hospital eye service for discharged patients once treatment has allowed the condition to stabilise with the potential for rapid re-referral should reactivation of proliferative eye disease occur.

Figure 11: R3A with pre-retinal fibrosis

Figure 12: R3S retina

Figure 13: R3S retina

An R3S grade is only valid if there are no significant changes from the baseline discharge images. These features are outlined in table 3.

Table 3: R3S Lesions

No Maculopathy M0

Maculopathy is defined in terms of the lesions evident within the macular region and visual acuity is a factor in making the diagnosis. In the absence of any of the defined markers for diabetic maculopathy (see below), the image is graded M0, even if there is background diabetic retinopathy present in the macula.

Maculopathy M1

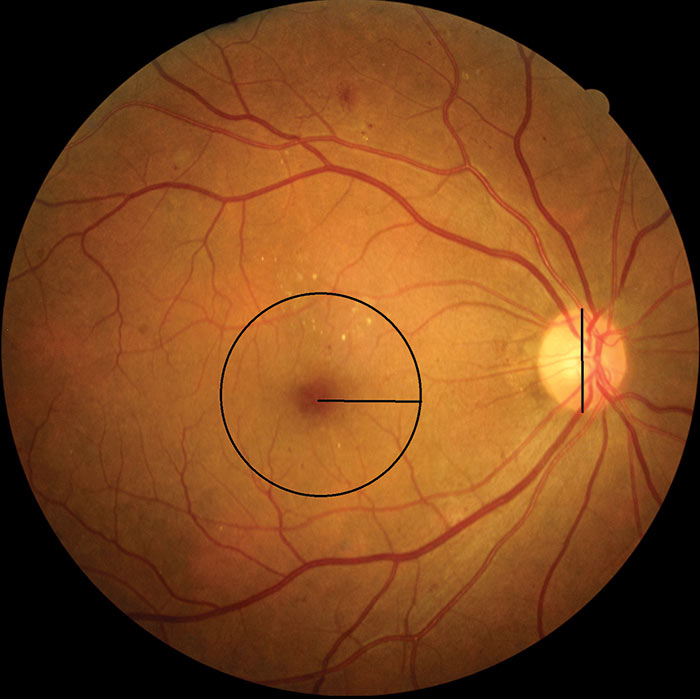

The English National Diabetic Eye Screening Programme defines the macula as that part of the retina which lies within a circle centred on the centre of the fovea whose radius is the distance between the centre of the fovea and the temporal margin of the disc. It is effectively the area of retina lying between the vascular arcades.

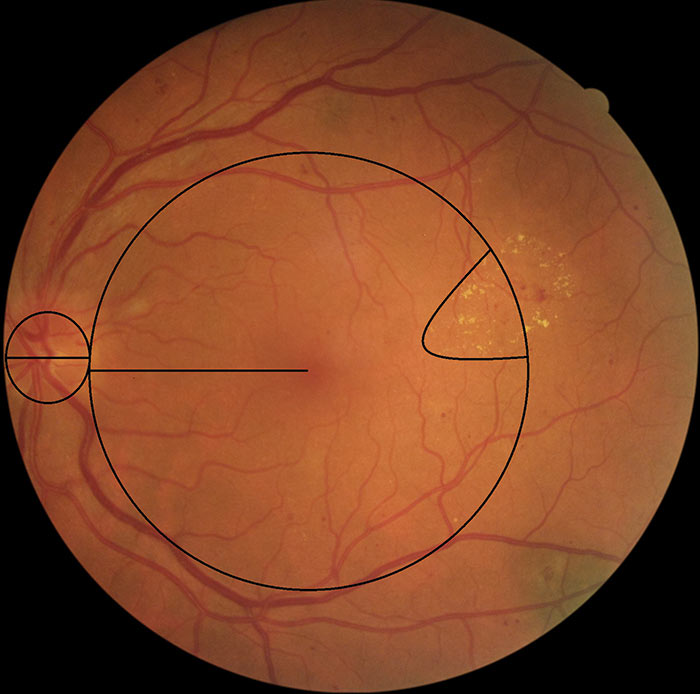

Figure 14: M1 with changes within 1 disc diameter of foveal centre

The most common cause of significant sight loss in diabetic eye disease is diabetic maculopathy because this is the region of the retina responsible for good visual acuity and colour vision. The macula is particularly prone to the accumulation of fluid within the retinal layers as a result of vessel leakage. The disruption of the retina through distortion from fluid accumulation is what causes the drop in visual acuity. Ophthalmologists identify patients with Clinically Significant Macular Oedema as those requiring treatment because it is this oedema that disrupts the foveal receptors and affects vision.

Clinically Significant Macula Oedema (CSMO) is defined by the ETDRS (Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study) as any of the following retinal features:

- Thickening of the retina at or within 500 microns of the centre of the macula.

- Hard exudates at or within 500 microns of the centre of the macula, if associated with thickening of the adjacent retina (no residual hard exudates remaining after the disappearance of retinal thickening).

- A zone or zones of retinal thickening one disc area or larger, any part of which is within one disc diameter of the centre of the macula.

Figure 15: M1 with circinate exudates

Clinically Significant Macula Oedema is by definition a thickening of the retina at the macula and consequently it is best seen with stereoscopic techniques such as Slit Lamp Biomicroscopy with Volk lens or by the use of OCT giving a cross sectional view of the macula that allows regions of fluid accumulation to be easily seen.

CSMO cannot be overtly detected in 2D views such as the digital photographic images used in the screening programme. To be able to grade diabetic maculopathy from digital images requires the use of Surrogate Markers which are retinal changes within classified zones of the macula that strongly correlate to the presence of macula oedema. These surrogate markers do not guarantee the presence of macular oedema and images showing signs of visible diabetic retinopathy within the macula region may or may not have clinically significant macula oedema present.

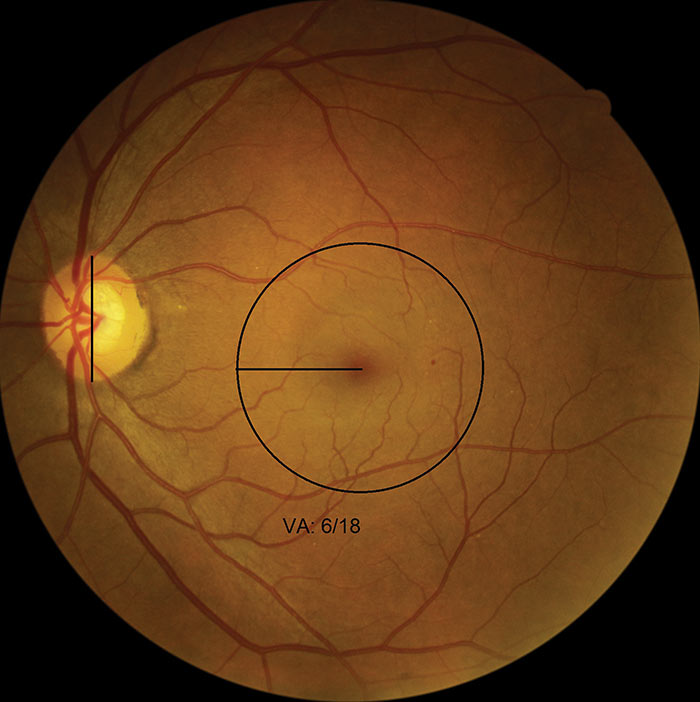

Figure 16: M1 with microaneurysms

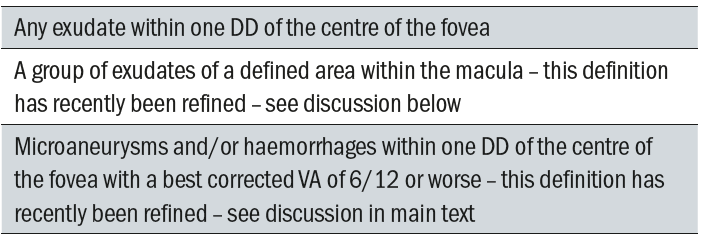

The surrogate markers currently used in this grading scheme are outlined in table 4.

Table 4: Surrogate Markers for CSMO

The definition of a group of exudates has now been classified as follows:

A group of exudates is an area of exudates that is greater than or equal to half the disc area and this area (of greater than or equal half the disc area) is all within the macular area.

In order to ascertain the area of exudates, the outer points of the exudates are joined and this enclosed area compared to half the area of the optic disc. Reference images have been provided and can be accessed at:

Four reference images have been provided – two are considered M1 referable maculopathy and two are considered to be M0.

Visual acuity is a crucial element in deciding if the presence of microaneurysms or haemorrhages within 1 DD of the foveal centre can be considered a marker for maculopathy. There will be cases when the VA is less than or equal to 6/12 and microaneurysms or haemorrhages present within one disc diameter of the centre of the fovea, but if the screener has documented known amblyopia, or there is AMD (which may also show exudates within the macula) to account for the poor VA, then:

- These images should be graded by the ROG grader and a decision made from the available information whether it is considered that the reduced vision is due to the amblyopia, the AMD or diabetic maculopathy.

- If the ROG decides the reduced vision is due to the amblyopia or AMD, the maculopathy should be graded as M0 and local protocols should be followed for referral of non-DR lesions if appropriate.

- If the ROG decides that the reduced VA could be caused by diabetic maculopathy, the maculopathy should be graded as M1 and the patient should follow the nationally recommended DR referral pathway.

If an image is determined to be an M1 grade then the patient should be referred to see an ophthalmologist within three weeks of their screening event and receive their first consultation within 13 weeks of the screening event.

The role of OCT in the detection and management of Diabetic Maculopathy

There is currently a London-wide CQUIN initiative (Commissioning for Quality and Innovation) to develop an OCT pathway across all the London screening programmes to reduce the demand on ophthalmology for cases of early maculopathy where there is no macula oedema although the surrogate markers indicate an M1 grade.

In the London North East DRS programme we have an OCT at one of our screening sites. At this site patients recalled with the digital surveillance pathway as early maculopathy and who are seen at a six-monthly interval will receive an OCT scan, as will patients where the photographer determines suspicious changes within the macula. The patient is still graded according to the grading criteria discussed above but if there is no CSMO they are kept within the surveillance pathway and reviewed in a further six months. In this way the OCT can help refine the management options available and reduce the demand on ophthalmology.

Olson et al 2013 carried out a health technology assessment into the economic value of photographic screening for detecting diabetic macular oedema by OCT. This was a multicentre study which found that costs were reduced from £985 per incidence of macular oedema being detected using a higher specificity, simple manual grading system, to £528 when coupled with OCT in the screening pathway. Olson concluded that introducing OCT into the pathway results in ‘cost savings without reducing health benefits’.

A Clinical Audit published by Fiona Heggie in May 2015 has reviewed the use of OCT for detecting diabetic macular oedema following maculopathy feature recognition on single field fundus photographs. The audit results suggest that OCT is effective in detecting fluid accumulation and when used in conjunction with retinal photography review, visual acuity recordings and patient ophthalmic history can forge a role within the diabetic retinal screening service. A two-stage screening process could be implemented for patients with suspicious maculopathy features. Effective screening for retinopathy combined with OCT use for patients with macular pathology as part of a two-stage process could therefore prove to be an efficient and effective use of resources. This two-stage process could effectively reduce the increasing demands on the hospital eye care services.

Laser Photocoagulation P1

If there is evidence of previous photocoagulation including focal or grid macula laser or peripheral pan-retinal photocoagulation then a ‘P’ grade is also allocated. Evidence of previous laser is graded P1.

Unassessable images U

As discussed earlier in this article some images will not meet the criteria for ‘adequate to grade’ after first studying them carefully for any evidence of referable retinopathy. Note: As mentioned earlier, if referable retinopathy is detectable on an otherwise poor quality image it is considered Adequate and the patient referred according to the referral pathway deadlines (see above). Any image graded within the pathway as ‘U’ is then assessed by a Referral Outcome Grader. In some cases the poor image quality may have been a technical issue and the patient should be recalled for a further digital imaging session as soon as possible. If the poor image quality is more ‘organic’ and relates to the quality of the ocular media, or persistent poor dilation (as sometimes happens following cataract surgery or in eyes with a dark iris) or poor mobility resulting in difficulty getting some or any digital images then the patient should be graded ‘U’ and recalled to a slit lamp clinic. If the screening programme has a policy of obtaining Anterior Eye images in such cases, these can help in deciding the cause of the poor quality image. Arrangements for the provider of slit lamp clinics to the eye screening programme may differ between programmes depending upon how the service has been commissioned. Patients should be seen within 13 weeks of the initial screening encounter.

Conclusion

Diabetes eye disease is a progressive retinal condition that if it is not managed appropriately, either in the early stages by good management of the blood glucose levels and blood pressure or in the later stages by good attendance at HES appointments, can then lead to severe sight loss. There is now a national screening programme set up to monitor all patients with diabetes over the age of 12 years. Early signs of overt diabetic eye disease can be detected by the screening programme and it is possible to catch the disease process at an early and more manageable stage. There is little reason for anyone to go blind these days as a result of diabetic eye disease.

However, there is always more that can be done, especially trying to reach those patients who persistently fail to attend eye screening and who are consequently much more at risk of developing sight threatening diabetic eye disease.

Quality grading of the retinal images according to the national programme protocols discussed above, allows for classification of patients according to the severity of the diabetic retinopathy and appropriate management pathways are followed to give patients the best chance of reducing the potentially devastating consequences of sight loss as a result of their diabetes.

Peter Mitchell is Senior Optometrist Grader London North East DESP.

References

- Venous loops and reduplications in diabetic retinopathy Prevalence, distribution, and pattern of development – Toke Bek Department of Ophthalmology, Århus University Hospital, DK-8000 Århus C, Denmark