Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea of the eye. This article will focus on uveitis in children but the description and classification of uveitis is the same in both adults and children.

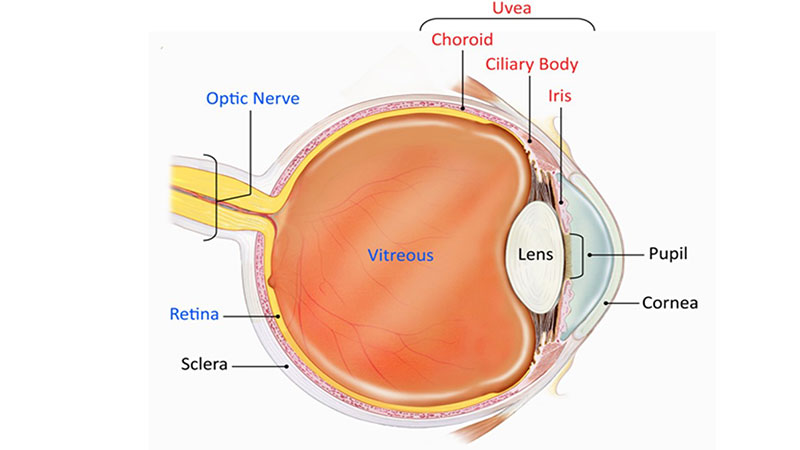

The uvea consists of the iris, choroid and ciliary body as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Diagram of the eye highlighting the components of the uvea in red1

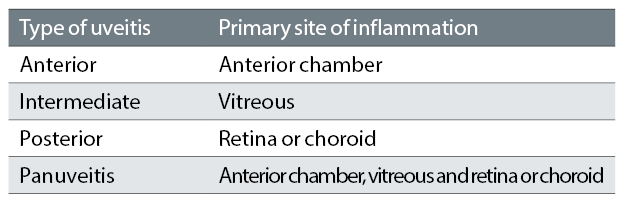

Anatomical classification of the site of uveitis activity divides uveitis into anterior, intermediate, posterior and panuveitis. The Standardisation of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) classification of the various types of uveitis are shown in table 1.2 Anterior uveitis is diagnosed when inflammation is limited to the iris, ciliary body, or both.2,3 Anterior uveitis is the most common type of uveitis.4-6

Table 1: The SUN working group anatomic classification of uveitis3

A cross-sectional study between 2009 and 2012 of 1,022 consecutive uveitis cases found that anterior uveitis made up 52% of cases, 23% were posterior, 15% panuveitis and 9% intermediate uveitis.6

Common signs of anterior uveitis include:

- Keratic precipitates

- Anterior chamber cells

- Anterior chamber flare

- Band keratopathy (BK)

- Posterior synechiae

- Conjunctival hyperaemia-usually circumcorneal (hyperaemia not present in all cases)

Intermediate uveitis signs include:

- Anterior vitreous cells

- Anterior vitreous flare

- Snow balls/snow bank in the vitreous

- Reduced VA

- Cystoid macula oedema

Posterior uveitis signs include:

- Retinitis

- Choroiditis

- Arterial and venous vasculitis

Grading systems for intraocular disease

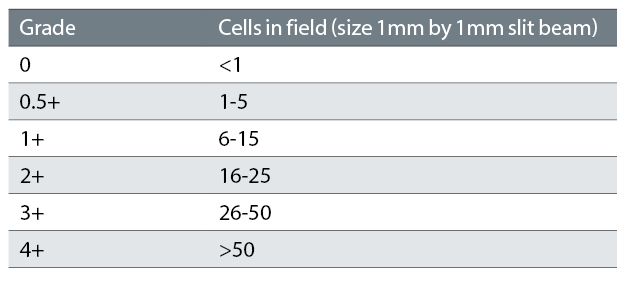

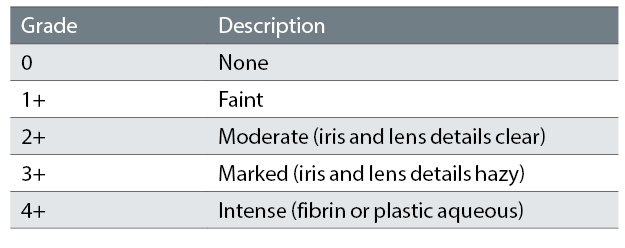

SUN grading is used for grading intraocular inflammation. For AC cells SUN criteria is a quantitative assessment of cell number in the AC, which is graded 0-4 (see table 2). Table 3 shows SUN grading for AC flare.3 There are no fully validated measures for determining the best prognostic and treatment response markers in paediatric uveitis: the SUN criteria are the most robust currently available. The same grading scheme is used for vitreous cells.

Table 2: SUN Working Group grading scheme for anterior chamber cells3

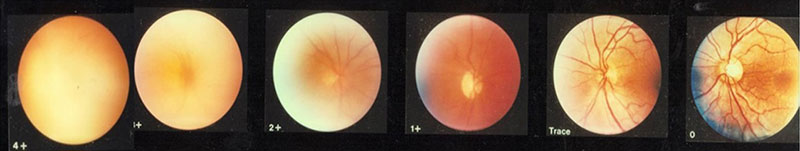

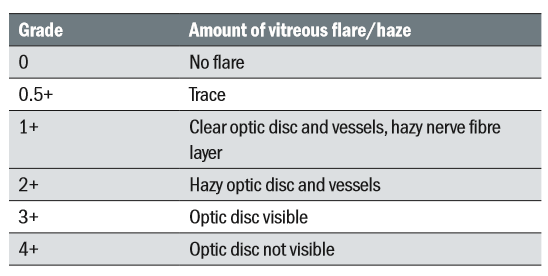

The Nussenblatt 6-step grading scale has been used for grading vitreous haze.11 The descriptive table is shown in table 4 and there is a series of photographs with each point in the scale representing the various degrees of fundus vitreous haze shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Photographic images for grading of vitreous haze7

The observer examines the eye with an indirect ophthalmoscope, then chooses the photograph which most closely simulates what is being seen.7

Table 3: SUN Working Group grading scheme for anterior chamber flare3

There is no consensus for grading of KPs. In vivo confocal microscopy may be a tool used in the future to aid grading and morphology of KPs.8-10

Table 4: Grading scale for vitreous haze7

Paediatric uveitis

Paediatric or childhood uveitis is defined as uveitis starting before the age of 17. It is relatively uncommon but causes ocular morbidity and acquired visual loss.11,12 While uveitis affects approximately 52 per 100,000 people per year (adults and children), paediatric uveitis accounts for only 5-10% of all cases.6, 13,14 In a study of children under 16 years with uveitis attending district hospitals in the UK between 1995 and 2001, Edelsten et al found the incidence to be 4.9/100,000.17

Clinical record keeping for paediatric uveitis can be complex as it must include:

- The chronicity of the disease

- Recording of multiple signs and symptoms including systemic disease

- Multiple treatments and treatment options.

Types of paediatric uveitis

Paediatric uveitis can appear as either the initial or secondary manifestation of a systemic illness. It may be isolated, ie not associated with any systemic disease (idiopathic) or associated with infection.15-17 There are some genetic associations of uveitis and their associated systemic diseases, for example human-leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27), a gene found in patients with certain auto-immune conditions.18,19

Systemic diseases associated with paediatric uveitis include:

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

- Tubulointerstitial nephritis (TINU)

- Sarcoidosis

- Behçets disease

- Psoriasis

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Vasculitis: Wegener’s, systemic lupus erthymatosus, Cogan’s, polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Takayasu’s arteritis, Kawasaki vasculitis.

Infectious causes of paediatric uveitis include:

- Toxoplasmosis

- Tuberculosis

- Herpes infection

As paediatric uveitis is associated with inflammatory systemic disease, multidisciplinary management involving rheumatologists, paediatricians, ophthalmologists, optometrists, family liaison officers and specialist nurses is desirable. A specific knowledge of the types of uveitis is beneficial for investigating causes and predicting the course of disease.20

Children presenting with uveitis with unknown cause should undergo investigations for associated systemic or infectious cause of their uveitis. This should include blood tests (full blood count, liver function, renal function, inflammatory markers, autoimmune screening, serum ACE, quantiferon gold), radiological investigations such as a chest x-ray plus multi-disciplinary input from paediatricians and rheumatologists.

In a retrospective, multi-centre study, Edelsten et al17 found that in referral cohorts at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, the most frequent diagnosis was juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (JIA-U) (67%) and in district hospitals (Windsor, Ipswich and Oxford Hospitals), it was idiopathic uveitis (78%). They found the most frequent type of uveitis up to seven years of age was chronic anterior uveitis but in eight to 15 years of age, it was posterior uveitis.

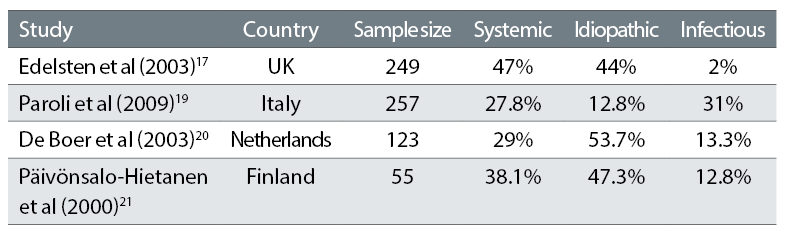

Table 5 shows the incidence of the main types of paediatric uveitis (all with uveitis diagnosed before age 16) reported from four studies in different European studies.17,19-21

Table 5: Incidence of main types of paediatric uveitis

These studies were based on clinical practice resembling that at GOSH in terms of similar demographics and access to treatment, and show that referral patterns to tertiary centres which report large series vary considerably between different centres. It is not clear how this may affect the reported frequency of complications and relative frequency of different diagnostic types. The inclusion of uveitis other than non-infectious uveitis varies between authors and there are known to be considerable differences between infectious causes of uveitis between countries. For example, infectious uveitis caused by toxoplasmosis and tuberculosis is more common in developing countries.21 This should be taken into account when comparing studies.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

JIA is defined as arthritis of at least six weeks’ duration without any other identifiable cause in children under 16.22 It is the most common rheumatic disease of childhood with an incidence of one in 10,000 in the UK and a female predominance.27 The most common extra-articular manifestation of JIA is uveitis.15,24 Additionally, JIA is the disease most commonly associated with paediatric uveitis.12,16,25 There are seven subtypes of JIA as defined by the 1997 International League of Associations for Rheumatology.26

- Systemic (arthritis with at least two weeks of daily fever)

- Oligoarticular (arthritis affecting one to four joints in the first six months)

- Rheumatoid factor (RF)-negative polyarticular (polyarticular – arthritis affecting five or more joints in the first six months)

- RF-positive polyarticular

- Enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) (enthesitis – inflammation at the sight of tendon/ligament insertion)

- Psoriatic (arthritis and psoriasis)

- Undifferentiated

British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) have jointly produced guidelines for screening of uveitis in JIA. These screening protocols may be found on the RCOphth website https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2006_PROF_046_JuvenileArthritis-updated-crest.pdf.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis (JIA-U)

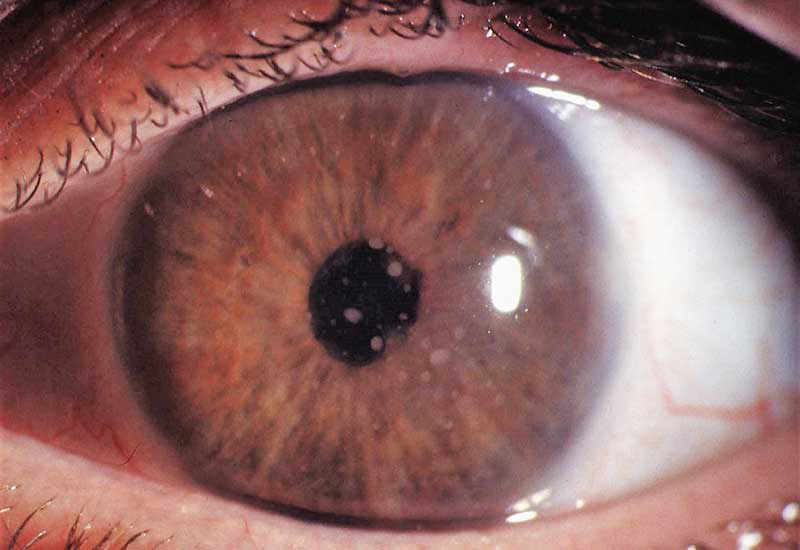

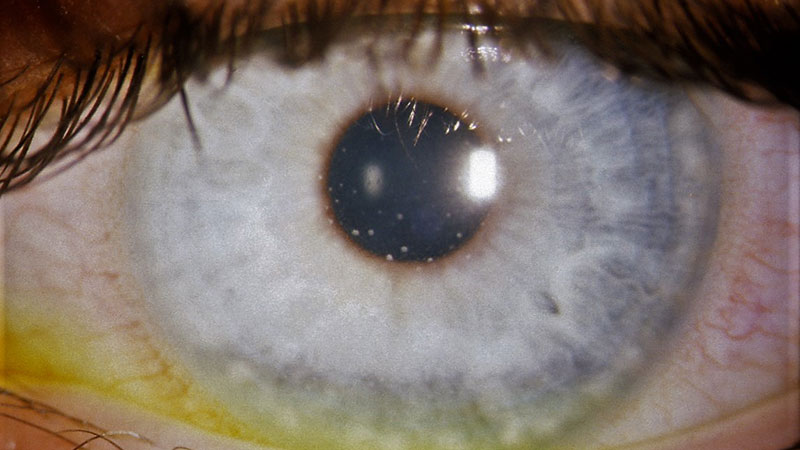

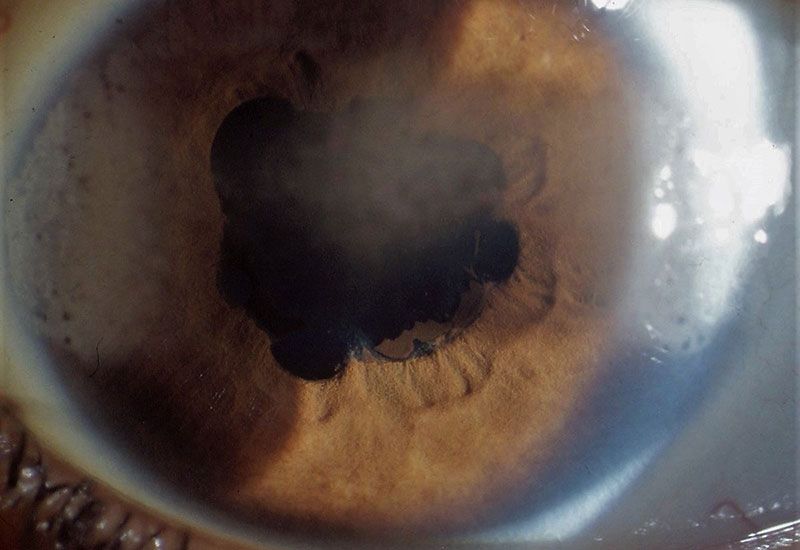

JIA-U is thought to be one of the most difficult eye diseases to manage in terms of its complications, medical and surgical management.27 It is usually a non-granulomatous chronic anterior uveitis that can cause vision loss and blindness.28 Occasionally there may be features of granulomatous anterior uveitis and severe cases can also develop intermediate uveitis.29,30 Granulomatous uveitis is characterised by large mutton-fat keratic precipitate (clusters of white blood cells on the corneal endothelium) shown in figure 3 and large inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber (epithelioid cells and macrophages).

Figure 3: Mutton fat keratic precipitates

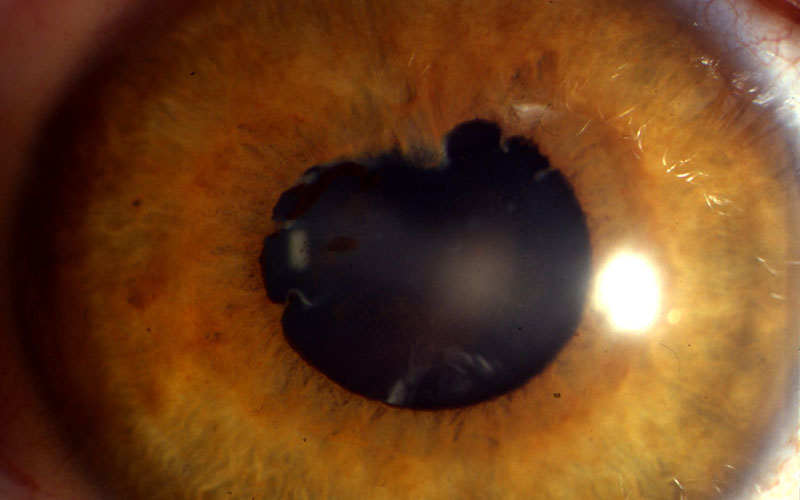

Non-granulomatous uveitis is characterised by fine keratic precipitates as shown in figure 4 and smaller inflammatory cells (lymphocytes) in the anterior chamber. JIA-U accounts for 67% of paediatric uveitis in the GOSH and St Thomas’ cohort as reported in 2003.31

Figure 4: Keratic precipitates in JIA-U

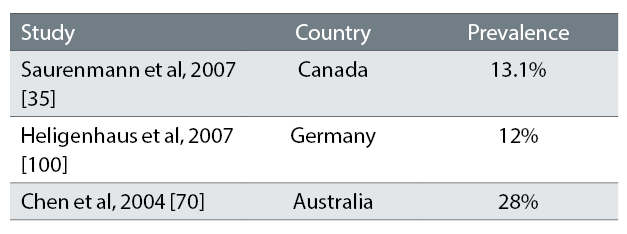

The reported frequency of uveitis varies (table 6) but up to 38% of patients will develop uveitis in the seven years following onset of JIA.29,32,33

Table 6: Studies showing the frequency of uveitis in JIA

The cumulative incidence of JIA-U varies according to geographic location, presence of anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), type of JIA and gender.34 Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) are a diverse group of antibodies that are directed against structures within the nucleus of the cell. They are found in patients whose immune system is predisposed to cause inflammation against their own body tissues. Approximately 30-50% of JIA-U have ocular complications present at time of diagnosis (see Visual outcome of JIA-U below).35 In Kanski’s cohort of 315 JIA-U patients in the UK, JIA preceded the diagnosis of uveitis in 94%.36

Risk factors for uveitis development in juvenile idiopathic arthritis

The risk factors that are most likely to cause uveitis in patients with JIA need to be identified in order to monitor and optimise adherence to screening protocols (BSPAR, 2006). The most common risk factors positively associated with the development of JIA-U are ANA positivity, oligoarticular JIA, female gender, early age of onset of arthritis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).32,36-39 However, other studies have reported that ANA positivity, gender and rheumatoid factor are not associated with JIA-U.39-41

Clinical course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis

The majority of children with JIA-U are asymptomatic.42 Two clinical presentations of uveitis in JIA have been described

- Chronic anterior uveitis

- Acute anterior uveitis with recurrent attacks.43

Uveitis can have a biphasic course showing high initial disease activity followed by quiescence and then a recurrence of inflammation during puberty.44 However, the majority have a chronic course lasting considerably more than three months, often several years.20,45,46

Visual outcome of JIA-U

The severity of JIA-U varies from a trivial self limiting disease to one causing bilateral blindness.47 Around 50-75% of those with severe uveitis will eventually develop visual impairment secondary to ocular complications such as cataract, glaucoma, band keratopathy (BK) and macular pathology.47-49 The risk factors for poor visual outcome in JIA-U include ANA positivity, early age of onset of arthritis, severe uveitis at onset, synechiae at presentation, presence of hypotony, short duration between arthritis and uveitis onset, >1+ anterior chamber (AC) flare at presentation, surgery during the course of uveitis and abnormal intraocular pressure (IOP) at presentation.38,48,50-52

Idiopathic uveitis

Idiopathic uveitis is defined as uveitis without a specific cause. A group of children exists with ocular disease clinically indistinguishable from JIA-U, who may or may not later develop JIA. This group is less well described, but their uveitis is phenotypically identical to JIA-U with the same complications and visual outcomes. There are also patients with uveitis of childhood onset phenotypically identical to those found in adulthood.

Idiopathic anterior uveitis in childhood and JIA-U differ in their clinical course. JIA-U manifests earlier, has more complications and more often requires systemic immunosuppression and surgical intervention.20

Complications of paediatric uveitis

Complications increase with the duration of disease and include cataract, glaucoma, BK, synechiae, macular oedema leading to impaired vision and even blindness.15,16,53 Severe visual impairment has been reported in up to 38% of patients.54 Some complications such as amblyopia and retinal detachment (RD) only occur in association with and subsequent to other complications. Some complications such as posterior synechiae and BK are not necessarily visually disabling.47

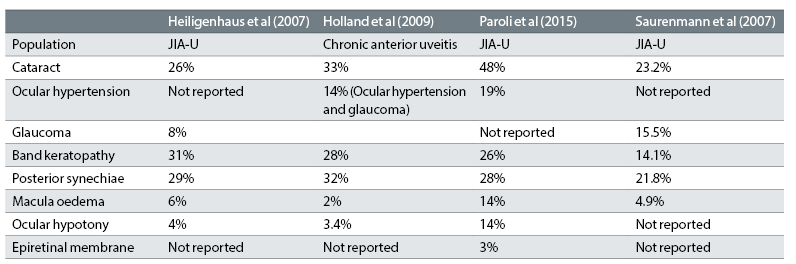

Woreta et al in their 2007 study, found at least one ocular complication was present in 67% of 132 eyes of patients with JIA-U and showed the most common causes of poor VA at presentation were cataract, central BK and glaucoma prior to presentation at the clinic. In an ocular coherence tomography (OCT) study, macular thickening is seen in over 80% of patients with 48% having evidence of macular oedema.55 This is higher than the figures reported in other studies (table 7).

Table 7: The main complications of paediatric uveitis and their incidence in four paediatric uveitis cohorts.29,32,49,52

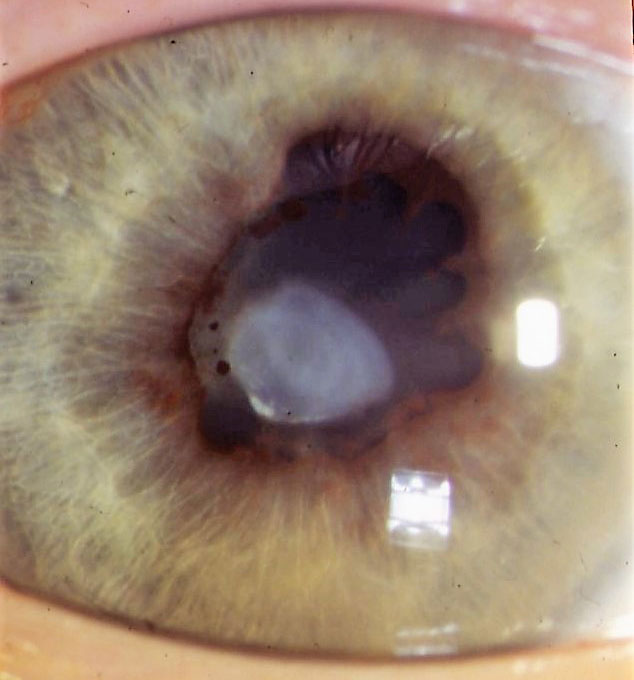

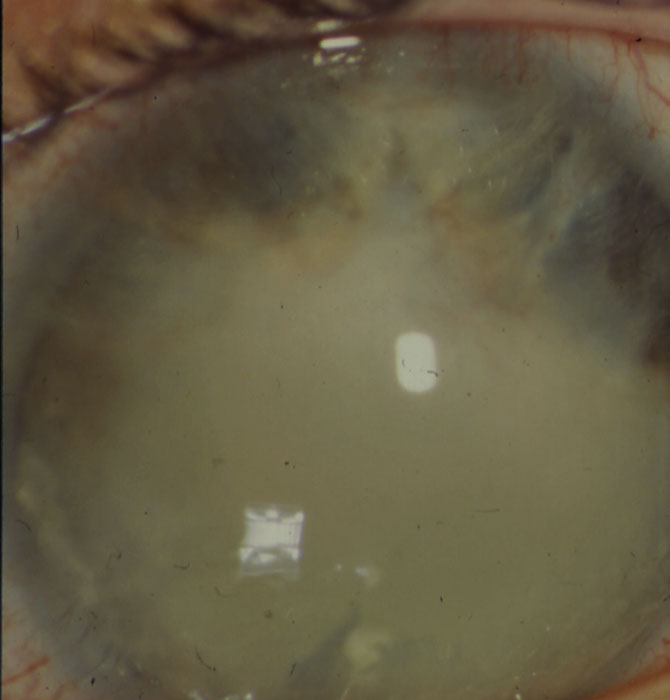

Secondary cataract

Cataract may be one of the earliest and most frequent complications in paediatric uveitis56,57 and can occur as a sequel of the longstanding inflammation or secondary to corticosteroid treatment or both.24,58 Most cataracts tend to be of the posterior subcapsular type as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Posterior subcapsular cataract and posterior synechiae as a result of uveitis

One study found the use of infrequent topical corticosteroids (≤3 drops daily) was associated with an 87% reduction in the risk of new-onset cataract when compared to four drops daily or more in JIA-U.24 The use of topical corticosteroids was associated with cataract formation independent of uveitis activity and the concomitant use of other forms of corticosteroid. Posterior synechiae at uveitis diagnosis has also been shown to be associated with the development of early cataract. Early treatment with Methotrexate (MTX) (see Treatment below) is associated with a mean delay for the need for cataract surgery of 3.5 years.24,50,59

Cataract surgery in children with paediatric uveitis poses a surgical challenge because of active inflammation, BK, anterior and posterior synechiae and a small pupil.52,53 Good visual outcomes are critically dependent on the reduction of pre- and post-operative inflammation by aggressive medical management, careful surgical techniques and conscientious post-operative monitoring.48,53,54 Studies have shown good visual outcomes with older children, with the absence of amblyopia and with good pre- and post-operative inflammation control.63-65 In younger children, outcomes were not as favourable due to poor tolerance of contact lenses and poor compliance with amblyopia management.66

Cataract surgery with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in children with intraocular inflammation remains an ongoing controversy. The advantages of IOL implantation are obvious for visual rehabilitation and amblyopia prevention. However, in JIA-U, it has been associated with hypotony, cyclitic fibrous membrane formation, IOL deposits, cystoid macular oedema, rapid posterior synechiae development and iris bombé.58,68,69 Patients with paediatric uveitis undergoing cataract surgery without IOL implantation also may have poor visual outcomes from pre-existing synechiae, pre-existing and post-operative glaucoma and post-operative retinal complications including CMO.59,61,70

Secondary glaucoma

Glaucoma that develops secondary to paediatric uveitis has a high visual morbidity71,72 and also see https://uveitis.net/patient/glaucoma.php.

There are a number of mechanisms of elevated intraocular pressure in uveitis:

- Open angle glaucoma

- Inflammation results in blood cell debris and protein leakage from blood vessels into the aqueous which then block the trabecular meshwork resulting in raised intraocular pressure.

- Steroid induced glaucoma: steroid drops are commonly used in the treatment of uveitis which can cause a rise in intraocular pressure. This can happen within a month of starting the drops or can occur much later.

- Angle closure glaucoma: the anterior chamber angle may be narrowed from either posterior or anterior synechiae.

- Posterior synechiae is the adherence of the iris to the lens (see figures 4,5 and 8). This may be in isolated areas but if extensive may obstruct the flow of aqueous through the pupil (pupil-block) and out through the trabecular meshwork. This may cause a slow raise in IOP or a rapid raise in IOP if there is iris bombé where the iris bows forwards closing the anterior chamber angle.

- Anterior synechiae occur when the iris is adherent to the cornea or the sclera. These can bow forward and close the angle.

Diagnosing and treating glaucoma early has been shown to be beneficial in reducing visual loss.73

Band keratopathy

BK occurs secondary to chronic inflammation. It is characterised by a band of calcium across the cornea involving mainly Bowman’s layer. The band normally begins in the three and nine o’clock positions of the cornea (figure 6) and may or may not progress to cover the central cornea (figure 7).

This will affect the vision if it is across the visual axis, and can cause pain from corneal epithelial erosions.67 If the BK is causing problems, it can be surgically removed.

Figure 6: Band keratopathy at 3 and 9 o’clock but starting to appear in the central cornea in an eye with posterior synechiae

Posterior synechiae

Posterior synechiae is adherence of the iris to the lens (figure 8 and see figures 5 and 6). The mechanism of formation is thought to be related to inflammatory cells, fibrin and protein deposition which stimulates the formation of adhesion between structures. If substantial, the posterior synechiae may lead to iris bombé and secondary angle closure as described above.

Figure 7: Band keratopathy obscuring the visual axis

The use of cycloplegic drops in uveitis may break the adhesions and prevent further adhesions. Control of inflammation often prevents the formation of synechiae.

Figure 8: Posterior synechiae

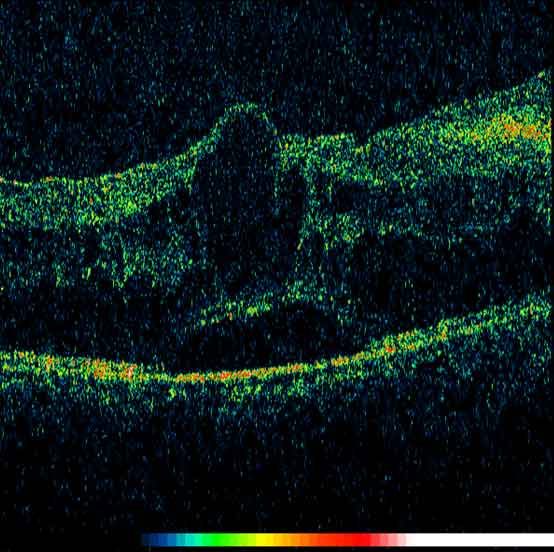

Macula oedema

Macula oedema is a sight threatening manifestation of uveitis which can lead to the loss of central vision and reduced visual acuity. It occurs as a consequence of chronic intraocular inflammation. It can be assessed clinically using a slit lamp, but the advances of imaging, in particular optical coherence tomography (OCT) aids in diagnosis and accurate monitoring of macula oedema (figure 9). Treatment of macula oedema may include steroid eye drops, oral steroids, steroid injections to the eye, anti-VEGF injections to the eye such as Avastin and the immunomodulatory drugs described below.75

Figure 9: OCT image of the macula showing cystoid macula oedema

Treatment of paediatric uveitis

The aim of treatment is to completely eliminate active inflammation in the eye. Kotaniemi et al (2014) retrospectively compared two cohorts of uveitis patients with JIA, diagnosed between 1990-1993 and 2000-2003. They showed the latter cohort had significantly fewer complications (21% vs 35%) and milder uveitis and concluded that early and aggressive treatment and close monitoring can lead to favourable outcomes with no consequent visual loss in most cases.76

Corticosteroids

The standard first line treatments of paediatric uveitis are topical and systemic corticosteroids. Prolonged systemic corticosteroids are nowadays reserved for severe disease in an effort to avoid the side effects such as growth retardation in children.77 Corticosteroid treatment is often effective in reducing inflammation but, as mentioned previously, it can lead to complications such as cataract and elevated IOP. The goal of treatment is to suppress inflammation in order to avoid the risk of further ocular complications resulting from either the uveitis or its treatment.78 Alternatives are necessary, therefore, to long-term steroid usage.

Second-line agents

The Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort study in the USA showed that the use of immunosuppressive drugs reduced the risk of vision loss by about 60%.51

Methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofitil Methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are all disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). DMARDs dampen down the underlying disease process, rather than simply treating symptoms. They reduce the activity of the immune system which may be overactive in some inflammatory conditions.

The most commonly used drug in all paediatric uveitis is MTX and many studies have shown its benefit in JIA-U.77,79-82 MTX is commonly prescribed in patients with arthritis. It is given once a week orally or as a sub-cutaneous injection. Although several other immunosuppressants can be used, MTX is the most effective for those with active arthritis, and switching from MTX to other conventional immunosuppressants often leads to worsening control of the arthritis even if the uveitis may be better controlled. Studies have shown that continued MTX treatment after quiescence of inflammation prevents earlier recurrence of JIA-U.40 In the GOSH cohort 55% of 62 comparable JIA-U patients have been shown to still have active uveitis following 15 months of treatment with MTX thus indicating the need for further treatments.83 Side effects of MTX can include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is an alternative to MTX and can control inflammation in approximately 50% of patients intolerant to or failing on MTX.84 MMF is also commonly used in systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. MMF is taken orally as liquid or tablets once or twice a day. The most common side effects of MMF are nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting or stomach pain.

Azathioprine has shown moderate success in the treatment of JIA-U.85 Azathioprine is also commonly used in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Azathioprine is given as tablets taken once or twice daily. Azathioprine can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, loss of appetite, hair loss and skin rashes.

All the DMARDs described above can affect blood count and liver function and make children more likely to develop infections. Regular blood tests are required for children taking DMARDs.

Biologics

Where conventional immunosuppression has failed, there has been increasing use of biologic treatments as second line agents, for example anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents. A number of anti-TNF drugs have been used in paediatric uveitis including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, golimumab as well as other biologics such as abatacept and tocilizumab.80-84 No life-threatening adverse reactions to anti-TNF treatment were recorded in the majority of studies.91-93

High levels of TNF-α have been detected in serum and aqueous humor of patients with uveitis.94 These observations have led to the initial justification for the use of anti-TNF agents in uveitis.95 Their benefit was first described as early as 200196 and they are now increasingly used for treatment of severe uveitis.

The Sycamore trial (a multi-centre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial) assessed the efficacy and safety of adalimumab in children and adolescents two years of age or older who had active JIA-U and were taking a stable dose of MTX. The trial showed adalimumab controlled inflammation and was associated with a lower rate of treatment failure than placebo among children and adolescents with active JIA-U who were taking a stable dose of MTX.97 Following the Sycamore trial, adaliumumab is now licensed for treatment of severe uveitis in children. Following three months of treatment with an appropriate dose of MTX (or sooner in the event of MTX intolerance) children with persistent active uveitis ≥+1 cells will be considered for treatment with adaliumumab by a specialised ophthalmology centre.

Go to www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/11/d12x02-paediatric-uveitis-anti-tnf.pdf for further information.

The Aptitude trial is currently under way. It is a multi-centre trial in the UK looking at the efficacy of the anti-TNF Tocilizumab. The trial aim is to see whether adding Tocilizumab to MTX for children with severe uveitis will prevent serious complications of JIA-U.

Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Paediatric Uveitis (PROMs)

Children with or without associated systemic disease are adversely affected in several ways:

- They have to use strong medication, possibly resulting in side effects.

- They need to attend multiple hospital appointments in various departments, impacting on school work.

- There is a constant worry of possible sight loss.

Visual impairment is an important component of quality of life in children with paediatric uveitis. One study showed that both the treatment and complications of paediatric uveitis have a significant impact on the quality of life and emotional well-being of patients. This is not only in terms of the discomfort experienced but also in perceptions of social isolation, anxiety and sense of injustice.98

At present there is no universally adopted questionnaire for use in paediatric uveitis and the only questionnaire available is the Effect of Youngsters’ Eyesight on Quality of Life (EYE-Q) which measures vision-related quality of life in children aged eight to 18 with JIA-U.99

Conclusion

Paediatric uveitis is a rare and complex eye disease associated with diagnostic challenges, differing treatment regimens which, if untreated, leads to multiple vision threatening complications.

Resham Pattani is an optometrist working at Great Ormond Street Hospital and Moorfields Eye Hospital.

Acknowledgement

Figures 3-9 are courtesy of Elizabeth Graham and Clive Edelsten.

References

1 National Eye Institute. Facts About Uveitis. 2011 9 February 2016]; Available from: https://nei.nih.gov/health/uveitis/uveitis.

2 Bloch-Michel, E and RB Nussenblatt, International Uveitis Study Group recommendations for the evaluation of intraocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol, 1987. 103(2): p. 234-5.

3 Jabs, DA, et al, Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol, 2005. 140(3): p. 509-16.

4 Chang, JH and D Wakefield, Uveitis: a global perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2002. 10(4): p. 263-79.

5 Yang, P, et al, Clinical patterns and characteristics of uveitis in a tertiary center for uveitis in China. Curr Eye Res, 2005. 30(11): p. 943-8.

6 Llorenç, V, et al, Epidemiology of uveitis in a Western urban multiethnic population. The challenge of globalization. Acta Ophthalmol, 2015. 93(6): p. 561-7.

7 Nussenblatt, RB, et al, Standardization of vitreal inflammatory activity in intermediate and posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology, 1985. 92(4): p. 467-71.

8 Wertheim, MS, et al, In vivo confocal microscopy of keratic precipitates. Arch Ophthalmol, 2004. 122(12): p. 1773-81.

9 Mocan, MC, S Kadayifcilar, and M Irkec, Keratic precipitate morphology in uveitic syndromes including Behçet's disease as evaluated with in vivo confocal microscopy. Eye (Lond), 2009. 23(5): p. 1221-7.

10 Kanavi, MR and M Soheilian, Confocal Scan Features of Keratic Precipitates in Granulomatous versus Nongranulomatous Uveitis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res, 2011. 6(4): p. 255-8.

11 Kump, LI, et al. Analysis of pediatric uveitis cases at a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmology, 2005. 112(7): p. 1287-92.

12 Cunningham, ET, Uveitis in children. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2000. 8(4): p. 251-61.

13 Gritz, DC and IG Wong, Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology, 2004. 111(3): p. 491-500; discussion 500.

14 Zierhut M, et al. Uveitis in children. Int Ophthalmol Clin, 2005. 45(2): p. 135-56.

15 Kanski, J.J., Uveitis in juvenile chronic arthritis: incidence, clinical features and prognosis. Eye (Lond), 1988. 2 ( Pt 6): p. 641-5.

16 Tugal-Tutkun, I., et al., Changing patterns in uveitis of childhood. Ophthalmology, 1996. 103(3): p. 375-83.

17 Biester, S., et al., Adalimumab in the therapy of uveitis in childhood. Br J Ophthalmol, 2007. 91(3): p. 319-24.

18 Martin, T.M. and J.T. Rosenbaum, An update on the genetics of HLA B27-associated acute anterior uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2011. 19(2): p. 108-14.

19 Kalinina Ayuso, V., et al., Pathogenesis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis: the known and unknown. Surv Ophthalmol, 2014. 59(5): p. 517-31.

20 Heinz, C., et al., Chronic uveitis in children with and without juvenile idiopathic arthritis: differences in patient characteristics and clinical course. J Rheumatol, 2008. 35(7): p. 1403-7.

21 Tugal-Tutkun, I., Pediatric uveitis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res, 2011. 6(4): p. 259-69.

22 Petty, R.E., et al., Revision of the proposed classification criteria for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Durban, 1997. J Rheumatol, 1998. 25(10): p. 1991-4.

23 Symmons, D.P., et al., Pediatric rheumatology in the United Kingdom: data from the British Pediatric Rheumatology Group National Diagnostic Register. J Rheumatol, 1996. 23(11): p. 1975-80.

24 Thorne, J.E., et al., Risk of cataract development among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis treated with topical corticosteroids. Ophthalmology, 2010. 117(7): p. 1436-41.

25 Kadayifçilar, S., B. Eldem, and B. Tumer, Uveitis in childhood. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus, 2003. 40(6): p. 335-40.

26 Petty, R.E., et al., International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol, 2004. 31(2): p. 390-2.

27 Abu Samra, K., et al., Current Treatment Modalities of JIA-associated Uveitis and its Complications: Literature Review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2016: p. 1-9.

28 Foster, C.S., Diagnosis and treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2003. 14(6): p. 395-8.

29 Heiligenhaus, A., et al., Prevalence and complications of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a population-based nation-wide study in Germany: suggested modification of the current screening guidelines. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2007. 46(6): p. 1015-9.

30 Dana, M.R., et al., Visual outcomes prognosticators in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis. Ophthalmology, 1997. 104(2): p. 236-44.

31 Edelsten, C., et al., Visual loss associated with pediatric uveitis in english primary and referral centers. Am J Ophthalmol, 2003. 135(5): p. 676-80.

32 Saurenmann, R.K., et al., Prevalence, risk factors, and outcome of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a long-term followup study. Arthritis Rheum, 2007. 56(2): p. 647-57.

33 Sabri, K., et al., Course, complications, and outcome of juvenile arthritis-related uveitis. J AAPOS, 2008. 12(6): p. 539-45.

34 Carvounis, P.E., et al., Incidence and outcomes of uveitis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, a synthesis of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2006. 244(3): p. 281-90.

35 Chia, A., et al., Factors related to severe uveitis at diagnosis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a screening program. Am J Ophthalmol, 2003. 135(6): p. 757-62.

36 Kanski, J.J., Screening for uveitis in juvenile chronic arthritis. Br J Ophthalmol, 1989. 73(3): p. 225-8.

37 Berk, A.T., N. Koçak, and E. Unsal, Uveitis in juvenile arthritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2001. 9(4): p. 243-51.

38 Kotaniemi, K., et al., Occurrence of uveitis in recently diagnosed juvenile chronic arthritis: a prospective study. Ophthalmology, 2001. 108(11): p. 2071-5.

39 Pelegrín, L., et al., Predictive value of selected biomarkers, polymorphisms, and clinical features for oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2014. 22(3): p. 208-12.

40.Reininga, J.K., et al., The evaluation of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients: are current ophthalmologic screening guidelines adequate? Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2008. 26(2): p. 367-72.

41 Cole, T.S., et al., Profiling risk factors for chronic uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a new model for EHR-based research. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J, 2013. 11(1): p. 45.

42 Wolf, M.D., P.R. Lichter, and C.G. Ragsdale, Prognostic factors in the uveitis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Ophthalmology, 1987. 94(10): p. 1242-8.

43 Kanski, J.J., Anterior uveitis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Ophthalmol, 1977. 95(10): p. 1794-7.

44 Hoeve, M., et al., The clinical course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis in childhood and puberty. Br J Ophthalmol, 2012. 96(6): p. 852-6.

45 Grassi, A., et al., Prevalence and outcome of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis and relation to articular disease. J Rheumatol, 2007. 34(5): p. 1139-45.

46 Kalinina Ayuso, V., et al., Relapse rate of uveitis post-methotrexate treatment in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol, 2011. 151(2): p. 217-22.

47 Edelsten, C., et al., An evaluation of baseline risk factors predicting severity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis and other chronic anterior uveitis in early childhood. Br J Ophthalmol, 2002. 86(1): p. 51-6.

48 Woreta, F., et al., Risk factors for ocular complications and poor visual acuity at presentation among patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol, 2007. 143(4): p. 647-55.

49 Holland, G.N., C.S. Denove, and F. Yu, Chronic anterior uveitis in children: clinical characteristics and complications. Am J Ophthalmol, 2009. 147(4): p. 667-678.e5.

50 Thorne, J.E., et al., Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: incidence of ocular complications and visual acuity loss. Am J Ophthalmol, 2007. 143(5): p. 840-846.

51 Gregory, A.C., et al., Risk factors for loss of visual acuity among patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Study. Ophthalmology, 2013. 120(1): p. 186-92.

52 Paroli, M.P., et al., Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-associated Uveitis at an Italian Tertiary Referral Center: Clinical Features and Complications. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2015. 23(1): p. 74-81.

53 de Boer, J., et al., Development of macular edema and impact on visual acuity in uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2015. 23(1): p. 67-73.

54 Ozdal, P.C., R.N. Vianna, and J. Deschênes, Visual outcome of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis in adults. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2005. 13(1): p. 33-8.

55 Ducos de Lahitte, G., et al., Maculopathy in uveitis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an optical coherence tomography study. Br J Ophthalmol, 2008. 92(1): p. 64-9.

56 de Boer, J., N. Wulffraat, and A. Rothova, Visual loss in uveitis of childhood. Br J Ophthalmol, 2003. 87(7): p. 879-84.

57.Kotaniemi, K. and H. Penttila, Intraocular lens implantation in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Ophthalmic Res, 2006. 38(6): p. 318-23.

58 Grajewski, R.S., et al., Favourable outcome after cataract surgery with IOL implantation in uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Acta Ophthalmol, 2012. 90(7): p. 657-62.

59 Sijssens, K.M., et al., Risk factors for the development of cataract requiring surgery in uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol, 2007. 144(4): p. 574-9.

60 Kanski, J.J. and G.A. Shun-Shin, Systemic uveitis syndromes in childhood: an analysis of 340 cases. Ophthalmology, 1984. 91(10): p. 1247-52.

61 Fox, G.M., et al., Causes of reduced visual acuity on long-term follow-up after cataract extraction in patients with uveitis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol, 1992. 114(6): p. 708-14.

62 Lam, L.A., et al., Surgical management of cataracts in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol, 2003. 135(6): p. 772-8.

63 Ganesh, S.K. and S. Sudharshan, Phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging, 2010. 41(1): p. 104-8.

64 Sijssens, K.M., et al., Long-term ocular complications in aphakic versus pseudophakic eyes of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol, 2010. 94(9): p. 1145-9.

65 Bohnsack, B.L. and S.F. Freedman, Surgical outcomes in childhood uveitic glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol, 2013. 155(1): p. 134-42.

66 BenEzra, D. and E. Cohen, Cataract surgery in children with chronic uveitis. Ophthalmology, 2000. 107(7): p. 1255-60.

67 Magli, A., et al., Cataract management in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: simultaneous versus secondary intraocular lens implantation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2014. 22(2): p. 133-7.

68 Foster, C.S., et al., Intraocular lens removal from [corrected] patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol, 1999. 128(1): p. 31-7.

69 Heiligenhaus, A., When should intraocular lenses be implanted in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated iridocyclitis? Ophthalmic Res, 2006. 38(6): p. 316-7.

70 Chen, C.S., D. Roberton, and M.E. Hammerton, Juvenile arthritis-associated uveitis: visual outcomes and prognosis. Can J Ophthalmol, 2004. 39(6): p. 614-20.

71 Foster, C.S., et al., Secondary glaucoma in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated iridocyclitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand, 2000. 78(5): p. 576-9.

72 Sijssens, K.M., et al., Ocular hypertension and secondary glaucoma in children with uveitis. Ophthalmology, 2006. 113(5): p. 853-9.e2.

73 Kotaniemi, K. and K. Sihto-Kauppi, Occurrence and management of ocular hypertension and secondary glaucoma in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: An observational series of 104 patients. Clin Ophthalmol, 2007. 1(4): p. 455-9.

74 Kwon, Y.S., Y.S. Song, and J.C. Kim, New treatment for band keratopathy: superficial lamellar keratectomy, EDTA chelation and amniotic membrane transplantation. J Korean Med Sci, 2004. 19(4): p. 611-5.

75 Karim, R., et al., Interventions for the treatment of uveitic macular edema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ophthalmol, 2013. 7: p. 1109-44.

76 Kotaniemi, K., et al., The frequency and outcome of uveitis in patients with newly diagnosed juvenile idiopathic arthritis in two 4-year cohorts from 1990-1993 and 2000-2003. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2014. 32(1): p. 143-7.

77 Sharma, S.M., A.D. Dick, and A.V. Ramanan, Non-infectious pediatric uveitis: an update on immunomodulatory management. Paediatr Drugs, 2009. 11(4): p. 229-41.

78 Kruh, J. and C.S. Foster, The philosophy of treatment of uveitis: past, present and future. Dev Ophthalmol, 2012. 51: p. 1-6.

79 Shetty, A.K., et al., Low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of severe juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoid iritis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus, 1999. 36(3): p. 125-8.

80 Foeldvari, I. and A. Wierk, Methotrexate is an effective treatment for chronic uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol, 2005. 32(2): p. 362-5.

81 Heiligenhaus, A., et al., Methotrexate for uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: value and requirement for additional anti-inflammatory medication. Eur J Ophthalmol, 2007. 17(5): p. 743-8.

82 Heiligenhaus, A., et al., Evidence-based, interdisciplinary guidelines for anti-inflammatory treatment of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int, 2012. 32(5): p. 1121-33.

83 Ramanan, A.V., et al., A randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of adalimumab in combination with methotrexate for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis (SYCAMORE Trial). Trials, 2014. 15: p. 14.

84 Sobrin, L., W. Christen, and C.S. Foster, Mycophenolate mofetil after methotrexate failure or intolerance in the treatment of scleritis and uveitis. Ophthalmology, 2008. 115(8): p. 1416-21, 1421.e1.

85 Goebel, J.C., et al., Azathioprine as a treatment option for uveitis in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Br J Ophthalmol, 2011. 95(2): p. 209-13.

86 Zulian, F., et al., Abatacept for severe anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2010. 62(6): p. 821-5.

87 Zannin, M.E., et al., Safety and efficacy of infliximab and adalimumab for refractory uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 1-year followup data from the Italian Registry. J Rheumatol, 2013. 40(1): p. 74-9.

88 Heiligenhaus, A., et al., Treatment of severe uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab). Rheumatology (Oxford), 2011. 50(8): p. 1390-4.

89 Mesquida, M., et al., Long-term effects of tocilizumab therapy for refractory uveitis-related macular edema. Ophthalmology, 2014. 121(12): p. 2380-6.

90 Miserocchi, E., et al., Long-term treatment with golimumab for severe uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2014. 22(2): p. 90-5.

91 Tynjälä, P., et al., Adalimumab in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated chronic anterior uveitis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2008. 47(3): p. 339-44.

92 Simonini, G., et al., Prevention of flare recurrences in childhood-refractory chronic uveitis: an open-label comparative study of adalimumab versus infliximab. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2011. 63(4): p. 612-8.

93 Saeed, M.U., et al., Etanercept in methotrexate-resistant JIA-related uveitis. Semin Ophthalmol, 2014. 29(1): p. 1-3.

94 Pérez-Guijo, V., et al., Tumour necrosis factor-alpha levels in aqueous humour and serum from patients with uveitis: the involvement of HLA-B27. Curr Med Res Opin, 2004. 20(2): p. 155-7.

95 Díaz-Llopis, M., et al., Treatment of refractory uveitis with adalimumab: a prospective multicenter study of 131 patients. Ophthalmology, 2012. 119(8): p. 1575-81.

96 Smith, J.R., et al., Differential efficacy of tumor necrosis factor inhibition in the management of inflammatory eye disease and associated rheumatic disease. Arthritis Rheum, 2001. 45(3): p. 252-7.

97 Ramanan, A.V., et al., Adalimumab plus Methotrexate for Uveitis in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(17): p. 1637-1646.

98 Sen, E.S., et al., Cross sectional, qualitative thematic analysis of patient perspectives of disease impact in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J, 2017. 15(1): p. 58.

99 Angeles-Han, S.T., et al., Development of a vision-related quality of life instrument for children ages 8-18 years for use in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2011. 63(9): p. 1254-61.